The game of baseball will forever remain a captivating battle between hitters and pitchers. As each side tries to outmaneuver the other, the game swings on a pendulum as to who has the advantage.

Every at-bat begins 0-0, giving both hitters and pitchers equal opportunity to make their mark. Pitchers always want to get ahead 0-1 with a first-pitch strike. As a natural correction, hitters have started swinging more at first pitches since they know it might be the most hittable pitch they get in an at-bat. They also no longer need to worry about “running up a pitch count” since most starting pitchers get chased by the elusive third time through the order anyway.

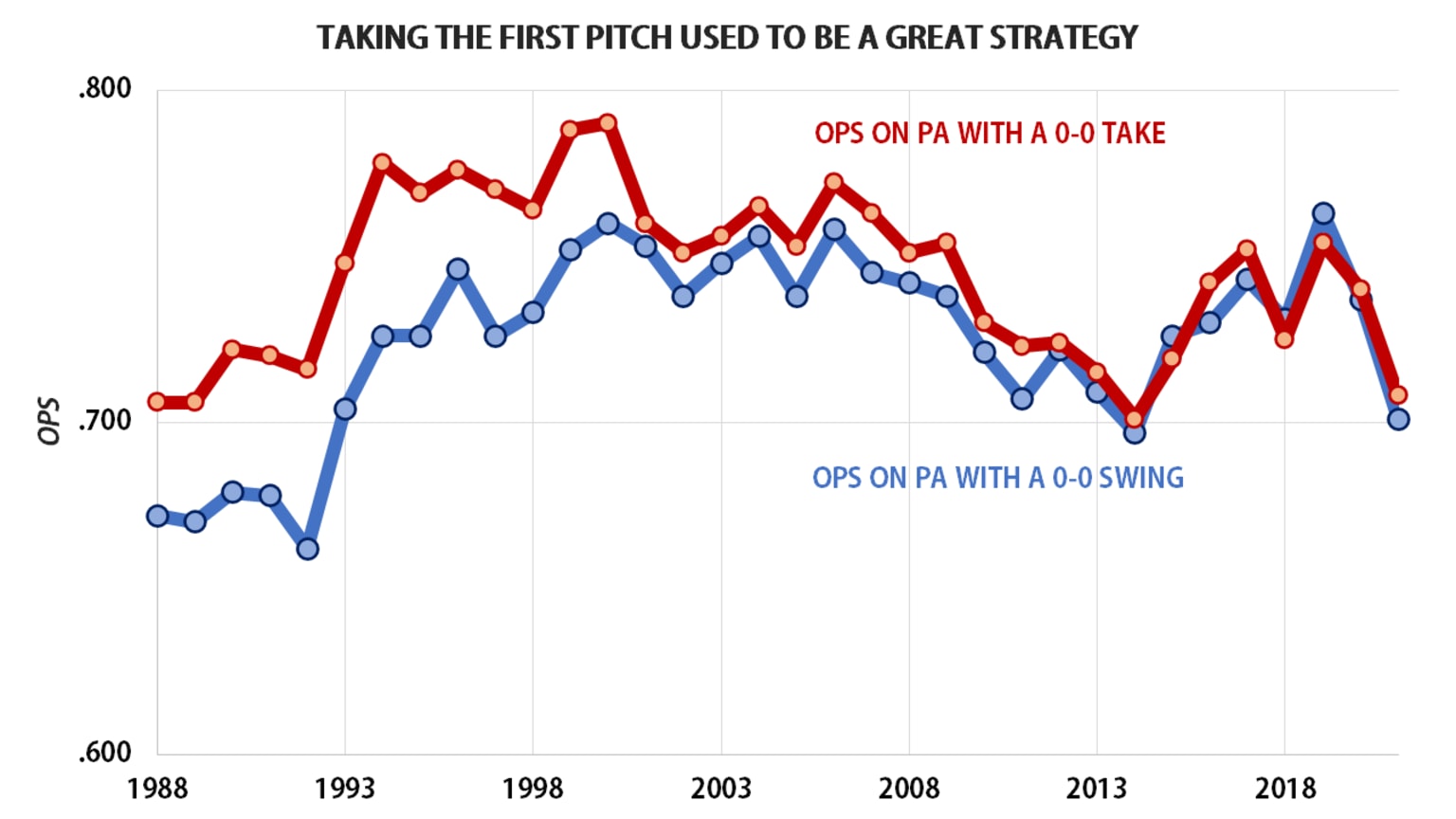

In 2021, Mike Petriello wrote about why hitters are attacking first pitches more than ever. Their performance on 0-0 pitches had noticeably improved, while their performance in two-strike counts worsened, making it worthwhile to attack earlier pitches.

Courtesy of MLB.com

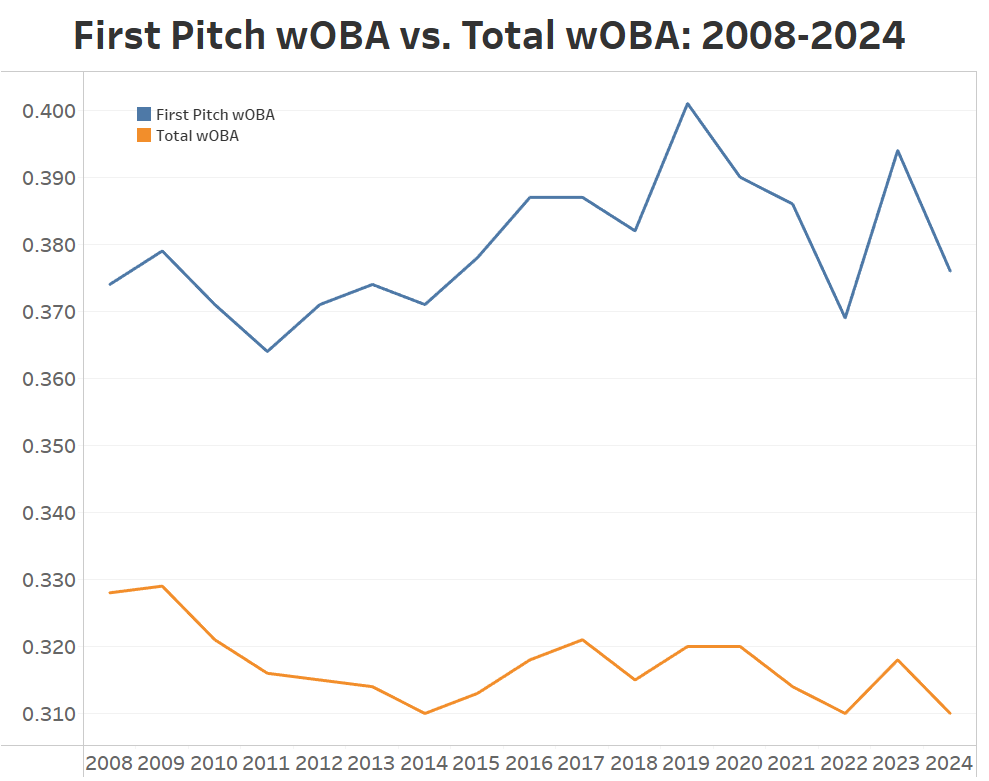

Though this has been one of the few opportunities for hitters to take advantage of pitchers, the trend is starting to reverse. Hitters have done worse against the first pitch compared to last year, including adjusting for the offensive environment.

This isn’t an outlier year overall, but it’s the biggest decrease in first-pitch wOBA in the sample. Pitchers have worked to fight this hitter development, and it seems to be making progress.

First-pitch strikes have reached an all-time high of 62.1%, and swing rate has reached an all-time high of 31.8%. The rise in first-pitch strike rate has a very strong correlation with swing rate (0.88 r-squared).

Did hitters get too aggressive on the first pitch? Swinging on 0-0 usually means your eyes light up as you get what you’re looking for (e.g. a fastball down the pipe). But swinging just to swing, expecting something good, might not work out. First-pitch whiff rates have been steadily climbing in this first-pitch count revolution. In 2024, batters are whiffing on 11.4% of first pitches, the highest value since 2008 (the beginning of the pitch tracking era).

However, there hasn’t been a discernable change in how pitchers are attacking 0-0 counts usage-wise. Across pitch groups (fastball, breaking, and offspeed), first-pitch usage has remained relatively stagnant.

There has been a shift within the fastball bucket for specific pitch types. In June, Justin Choi at FanGraphs wrote about how one fastball isn’t enough. He mentions that 0-0 four-seam fastballs are at a new minimum, and, by run value, sinkers and cutters are much better pitches to throw in as a first pitch (though I highly recommend reading the entire piece). That holds true as we’ve continued into the second half. Four-seam fastball usage is still down, with sinkers and cutters taking its place.

Nevertheless, that doesn’t fully explain a rising whiff rate. Being at an impasse with traditional data, I turned to Pitcher List’s own Pitcher Level Value (PLV). PLV quantifies pitch quality, similar to Stuff+ models. PLV gives us pitch quality but can also give hitter value for decisions and overall performance. For instance, a fastball thrown on the corner and hit for a home run will bring significant positive value, while whiffing at a hanging curveball in the middle of the strike zone will result in negative value.

Given that PLV houses much of the data I was looking for, I asked our own Director of Research and Analytics, Kyle Bland, for league-wide data on 0-0 pitches. Using the PLV modeling process, he compared 2024 to the last four years (what the PLV model is trained on).

Since the 2020-2023 data is pulled from an environment where hitters already swung at first pitches frequently, this isolates 2024’s changes.

Overall, the bat-to-ball hasn’t dramatically changed. Hitters are slightly more aggressive, making slightly better decisions and making slightly more valuable contact. This has led to a small increase in runs added from 0-0 counts.

The other two stats, power and pitch run expectancy, are where 2024 stands apart. Hitters are getting to less power on 0-0 than they have before, and they are seeing notably more difficult pitches. The power outage explains why wOBA is down. I don’t think the ball itself could be the source of that, though that is purely anecdotal (if someone smarter than me wants to investigate it).

Home runs are being hit at just over 2.0 per game and down 15% vs last year. A main reason appears to be that the ball isn’t flying as far.

Carry distance is on level with the notorious dead ball April of 2022. 🧵⬇️ pic.twitter.com/VeNNtuHVg0

— Ballpark Pal (@BallparkPal) April 17, 2024

Other than shenanigans about the baseball itself, pitchers have just increased their pitch quality on the first pitch. No longer are the days where a hitter can consistently expect a grooved fastball or hanging curveball.

They aren’t taking a step off the gas to recuperate energy for the rest of the at-bat. They know hitters are looking for something the second they step into the box and there’s no more “settling in”. It’s 0-60 before the first pitch is thrown, otherwise you may be looking at a ball in the seats. While first-pitch quality is up, that hasn’t affected workloads directly: starters have increased their innings per start over last season (5.28 vs. 5.14). Regardless, they’re working harder than ever, making sure hitters have as few advantages as possible.