Baseball is a sport of tinkering and constantly evolving, where players seek any edge over the competition. It’s very rare for a player to “figure it out” right away and then sustain that success. So, when Austin Riley started his career hitting 16 home runs in his first 49 games, you knew that there would be some sort of downfall. But for Riley, that downfall was more of an abyss. He finished off the second half of the 2019 season — 95 plate appearances — with an OPS of .486 (28 OPS+) and striking out 39 times (41% K).

Then, in 2020, Riley made a considerable effort to improve his plate discipline, cutting his strikeouts to a decent 23.8% and increasing his walk rate to 7.8%. But, there was no power to show along with that newfound discipline, as his barrel rate decreased from 13.7% to 10%. Now, his walks are up again to nearly 11%, accompanied by another increase in strikeouts (29%), but the barrel rate is back up near his 2019 levels, at 13.2%. The increased walk rate, combined with the raised barrel rate, has produced a slash line of .313/.407/.550 thus far. So, what changes are fueling his potential 2021 All-Star campaign?

Cleaning Up His Bat Path

Riley’s fatal flaw is the whiffs. In 2019, he swung and missed on nearly 22% of all the pitches he saw. In 2021, that figure is roughly 14%. One way of mitigating swings and misses is through the swing itself.

Here, we’ll look at a couple of home runs, one from 2019 and the second from this year, respectively. While both pitches vary in vertical location, horizontally both are along the same line, which gives us an opportunity to critique the swings. With that in mind, notice how Riley takes the second to right-center while the first is pulled.

https://gfycat.com/dishonestgloomyarctichare

https://gfycat.com/hospitablewarmheartedaustraliancurlew

The two results are not by accident. At live speed, it looks like Riley is staying linear and not swinging as intensely as he was in 2019. We can see this by isolating the point just before Riley commits to swinging the bat.

There are two things to see here. First, we have the legs. Riley is more closed off here, as evidenced by his back kneecap being covered in the latter, and visible in the former. This means Riley has seemingly made an effort to have a more controlled swing. But the second point is more important here. Notice how the bat is pointing in a similar direction, towards the pitcher, but pops up in line with the top of his head in 2021 and behind his neck in 2019 — it’s a minor change, but definitely apparent. Riley is not wrapping the bat around his body to the same degree this season, showing that Riley has made an adjustment to be shorter to the ball.

But this change was not just implemented for this year, it’s something you saw last year as well.

https://gfycat.com/leanimpeccablehalcyon

And for comparison:

Once again, the back kneecap is hidden behind the front leg, and the bat is in a similar position to what it is this season.

What’s great about this last GIF is that it’s a slider, on the outside edge of the plate, and he’s laced it down the left-field line. Granted, it was hung and not a great pitch, but for someone that whiffed on 30% of sliders the year prior, this is a drastic improvement.

Those simple adjustments are easily conveyable to his increased productivity, pitch by pitch.

Not only have Riley’s numbers improved against fastballs, but also against offspeed pitches. The 24-year-old mentioned how he’s been trying to get better against the changeup, driving it rather than rolling over as he’s done in the past.

As for the breaking pitches, you may be concerned that the SwStr% is still too high and that’s because of the slider. Of hitters facing at least 100 sliders this season, Riley has the 21st highest percentage of swings and misses. Normally that’s not a good thing, but with hitters like Nelson Cruz and Teoscar Hernández also in that tier, we don’t have to be overly concerned.

Being Selective

We spent the previous section addressing how Riley has been controlling the swing and miss in his game by tinkering with his swing. But that’s only half of the story. Riley has been able to decrease the strikeouts and hit for nearly the same amount of power as he did back in 2019 (.245 ISO in 2019, .223 ISO in 2021). This is something our own Chad Young talked about over the offseason, using expected walks and strikeouts in talking about Riley’s 2020 season, and the legitimate strides he made cutting down the whiffs. Chad’s piece also gets into how Riley might put the two past approaches together and what it could look like, inspiring me to explore why it happened in the first place.

Having covered the swings and misses already, we can now cover where Riley’s increased walks come from, using his swing and take decisions as a reference point.

Swinging fewer times in the shadow (48% compared to 67% in ‘19 and 64% in ‘20) has undoubtedly allowed Riley to draw more walks while also producing a greater run value at +12. However, there is more to this than just the walks. In the heart, Riley has been much better when swinging, producing a +8 run value, easily the highest of his career (-2 in ‘19, +2 in ‘20).

Throughout the last section, we looked at Riley’s condensed swing over the past two seasons and how it was critical to keeping down the strikeouts. But that doesn’t necessarily equate to being a positive for power. While being shorter to the ball could aid his power — think Justin Smoak’s revival — this isn’t something we can say with Riley, especially since he was barreling more balls in 2019 than he is now. However, we can postulate on where his regained power came from by going back to his +8 runs in the heart this season.

In the heart, Riley is swinging at fewer pitches (76%) compared to his prior seasons (83% in ‘19, 82% in ‘20). Since hitters are going to be better while swinging at pitches over the heart of the plate, you would think Riley’s production would be down. But, Riley has a plan in place.

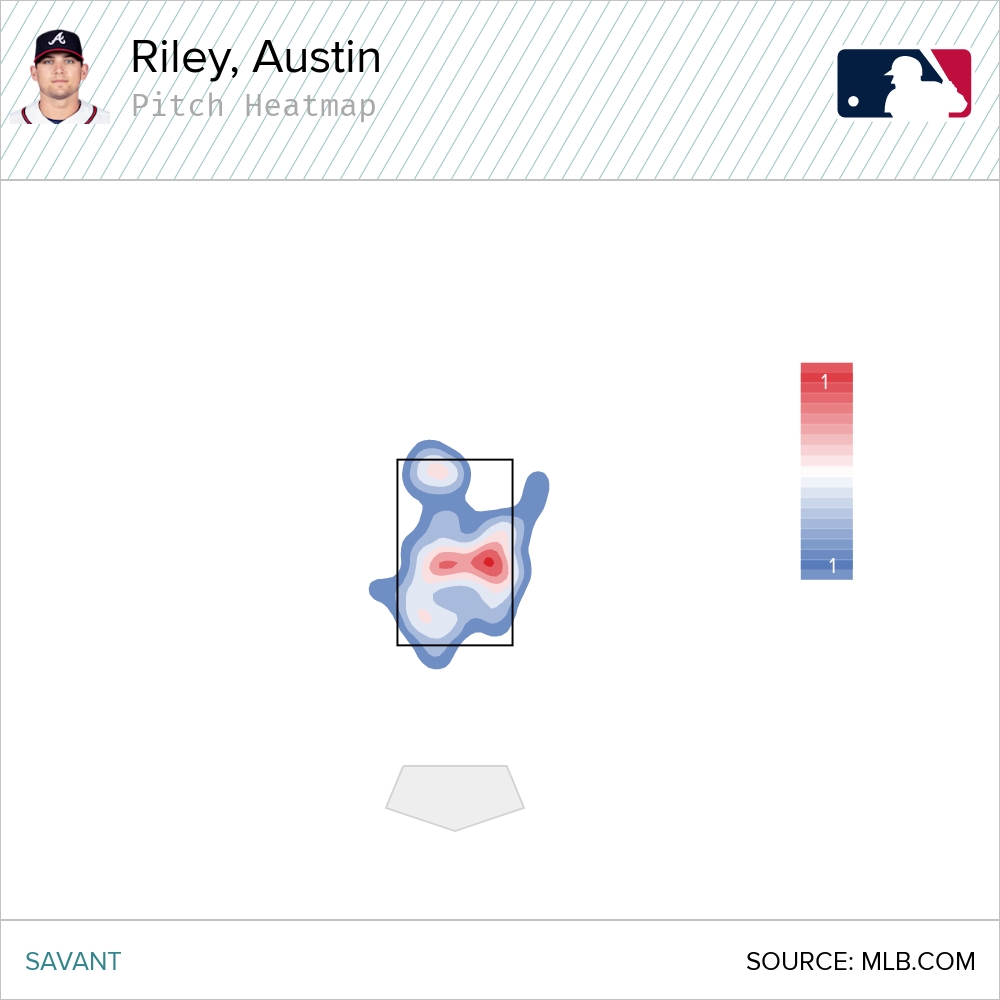

Below is a heatmap of every pitch Riley has barreled.

Those pitches are mostly located in the middle of the plate. Keep this in mind as we look at the pitches Riley has swung at throughout his career.

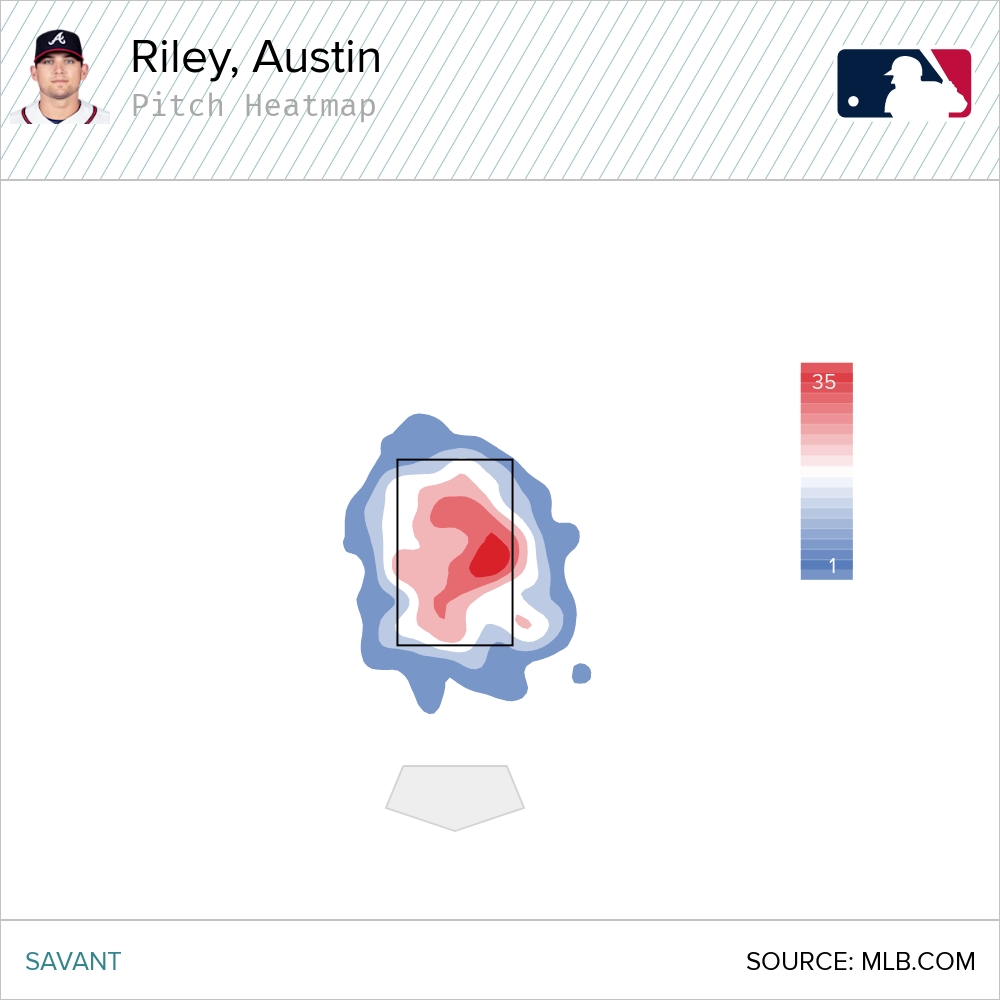

In 2019, Riley swung at a lot of pitches, with a good number of them middle-away.

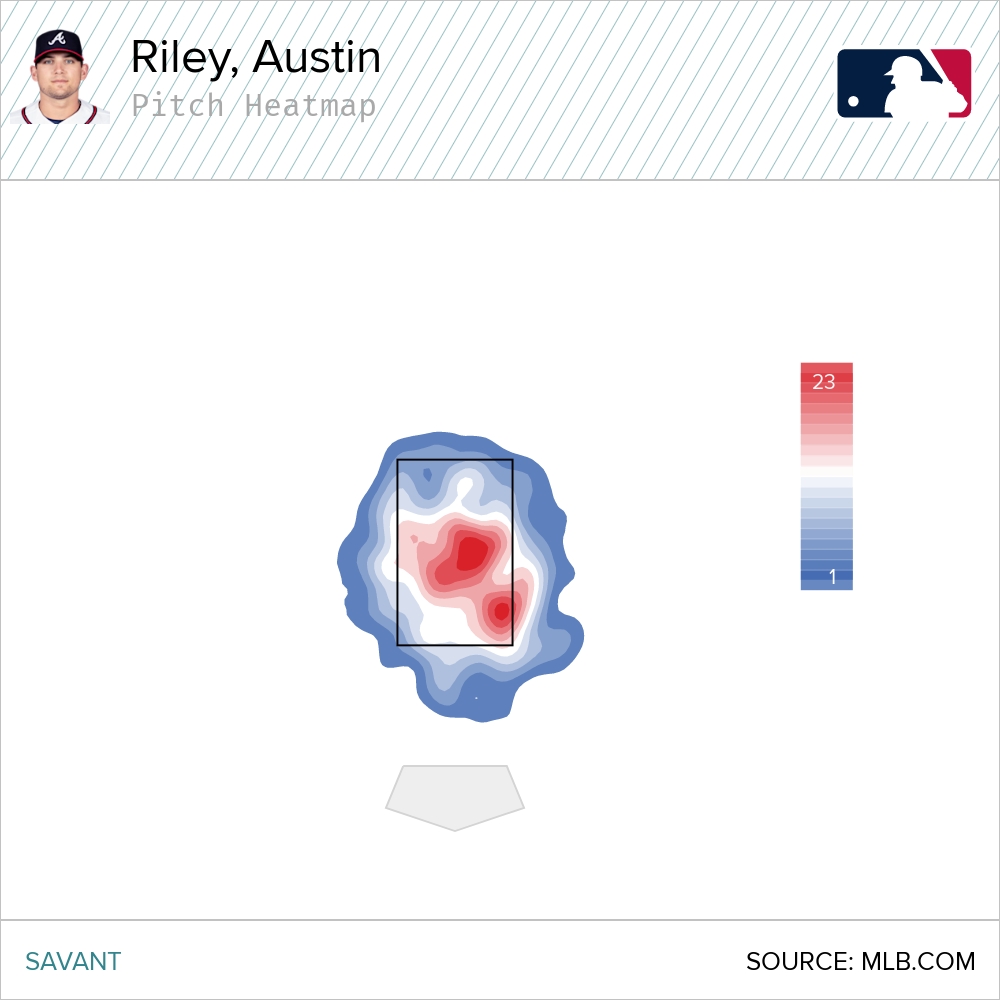

A year later, the slugging third baseman was a little more selective but still swinging at a lot of pitches in the zone, regardless of location.

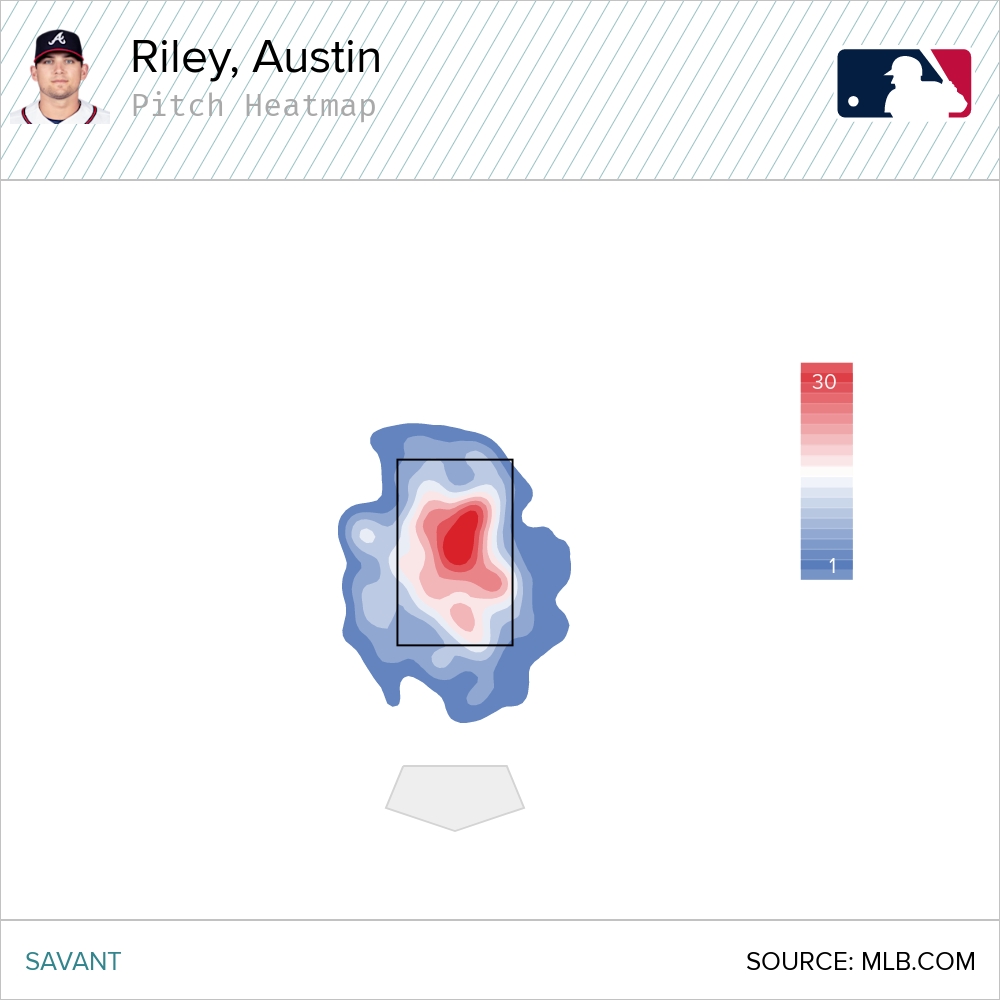

This season, Riley has tightened his zone to just the center part of the zone — slightly away if we’re being super discerning — but nevertheless, looks awfully similar to the image of Riley’s barrels.

We can sum this up numerically as well.

As a disclaimer, the wOBA and xwOBA statistics in this table are based on Riley’s total swings and not just those he just made contact with that would reflect wOBAcon or xwOBAcon.

In short, Riley’s “quality over quantity” swing approach is no doubt having a powerful impact on his game.

Conclusion

The first year was all power, the second was just focused on keeping the strikeouts down. In a crude assessment, you could say that Riley has combined both into his 2021 approach — but it’s not that simple. Riley has been able to keep his strikeouts down and push his power back to his sensational early 2019 form by cleaning up his bat path while also making an adjustment completely foreign to any prior season by focusing on hunting pitches he could do the most damage with.

But there have been a couple of flaws in this superb season for Riley so far. Firstly, Riley’s strikeouts have crept towards 30% this season. His selective approach is at least partially responsible for his strikeouts, where he’s swinging on the first pitch only 33.5% of the time, compared to over 40% in seasons prior. Furthermore, using our own player pages, we can see that Riley is taking strikes in early counts 21.7% of the time, significantly higher from 11.8% in 2019 and 13.8% in 2020. The other has been Riley’s number of groundballs, which has reached a career-high at 45.3%, which also doesn’t have a straightforward answer, but may be a byproduct of a career-low 10.5° average launch angle.

These issues will serve as another chance for Riley to make more adjustments in his quest to be a dominant force at the plate. Maybe I’ll even write another article about it.

Photo by John Adams/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Aaron Polcare

I figured that there would be an Austin Riley breakout piece. 7 HR in 9 games will do that. Here is one additional reason to be skeptical. Up until 2021, all Austin Riley has done is embarrass himself in MLB. I suspect that pitchers are probably being very aggressive with him. Hitting is more difficult when you get pitched tougher. He probably hasn’t been pitched tough yet, but that should change soon. I don’t have any actual thoughts about Riley – I don’t watch too many Braves games… but ATL seems to have a lot of players that people want to jump on – likely at least partially due to the strong lineup. Another factor which might be in his favor, he was a two-way player so his development very much could be a bit delayed. As always, GIF analysis should be taken very lightly. You could take his worst swings from 2021 and declare an emergency. A few game swings don’t tell you anything. Riley does not strike me as a special hitter, but I am always open to having him change my mind. I figure he looks like a high K, big power guy if he is a big leaguer… which I don’t think is a given… .408 BABIP alert. He is a zero defensively and base-running, so he needs to hit a lot. Riley has become a player that I am monitoring. I agree that he could be putting it all together in his third year, but a few weeks ago I thought he might be on his way out.

Do you have any numbers or evidence to support anything you just said?

Why don’t you think the Braves can win the NL this season?