When the Padres traded for Blake Snell, they thought they were getting an ace. It wasn’t long ago that Snell was one of the best per-inning starters in baseball. Walks may have been an issue, and he didn’t always stay healthy, but Snell was one of the most potent starters in baseball when he was on the mound. These past two calendar years, though, Snell has been anything but consistently dominant.

We’ll get to that. But before we do, here’s a taste of what Snell looks like at his best. The curveball, tossed in at the top of the zone for a called strike against Randal Grichuk:

https://gfycat.com/boilingfittinggrasshopper

A changeup, run well off the plate for a swinging strike:

https://gfycat.com/legitimatemajesticerne

An elevated fastball to change Grichuk’s eye level:

https://gfycat.com/bitterdirectguernseycow

And the curveball again to put him away:

https://gfycat.com/snoopychubbygrackle

Not only is it his most aesthetically pleasing pitch, but Snell’s curveball is also his best pitch. This at-bat is a perfect example of its versatility. He can throw it in the zone for called strikes, and he can spike it. He can’t say either of those things about his slider or his changeup. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise when I say that Snell hasn’t been the same since he lost his curveball.

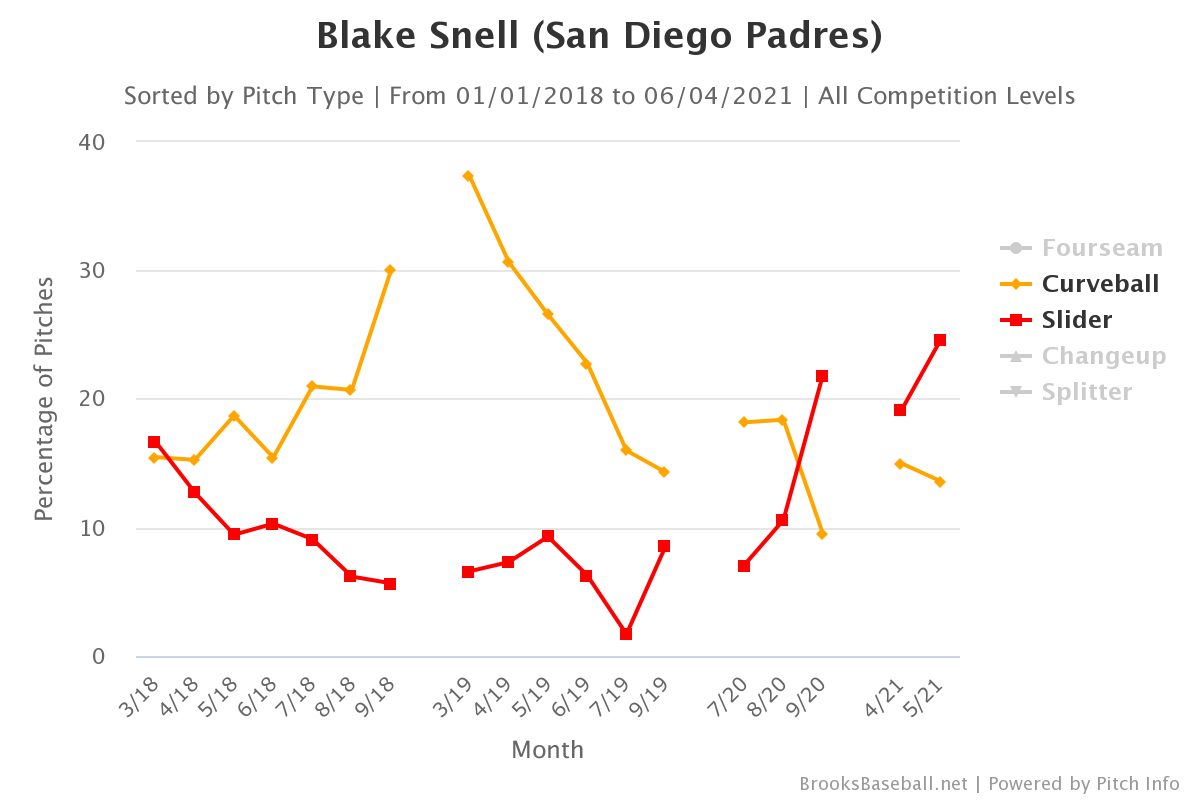

Snell’s monthly curveball and slider usage, since 2018:

In 2018 and 2019, Snell was a fastball pitcher, with lots of curveballs and changeups. But by the end of 2019, his curveball usage had dipped significantly, and it’s stayed below 20% since that point. But he also started to up his slider usage to the point where it’s his most-used secondary. His curveball has been relegated to his least-used pitch. That’s not a coincidence.

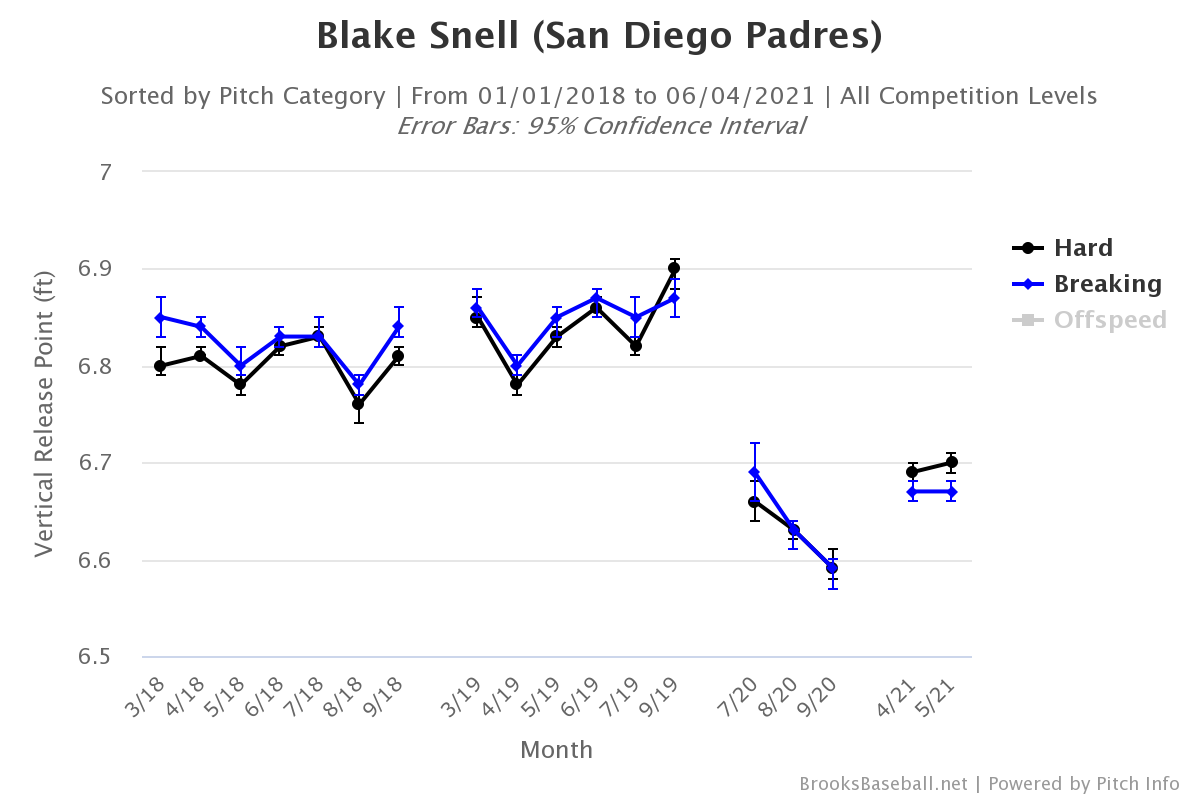

Consider Snell’s vertical release point, since 2018:

That may or may not seem like a big deal to you. I’d argue it is. I’ve been writing about this a bunch lately, but any given pitcher’s arm slot has a massive effect on the movement of the ball. Throw over the top like Justin Verlander, and you’ll see vertically-oriented pitches (i.e., with lots of ride or drop) that don’t have much horizontal movement. Drop down to the side like Aaron Nola, and you get more side-to-side movement, with lots of sink and sweep.

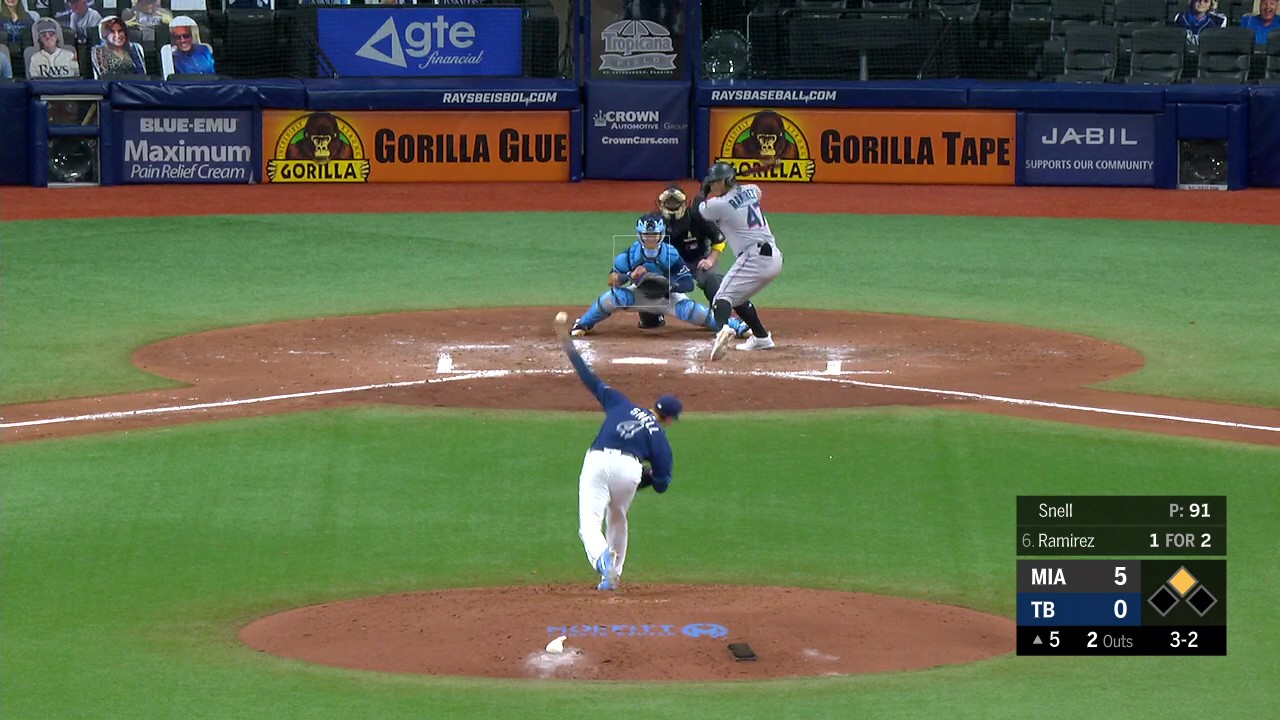

From 2018 to 2019, Snell ranked in the 98th percentile in vertical release point. Part of that is being 6’4″ with long limbs, but it’s mostly because his arm slot looks like this:

Snell is still plenty extreme by vertical release point. He still ranks in the top six in vertical release point. It’s certainly not a flaw in the numbers. In the past two years, his arm slot has looked more like this:

Snell’s arm slot has dropped down considerably, from just about as straight up and down as you can get towards a more traditional three-quarters arm slot. That’s had significant, significant reverberations on the movement of his pitches. In particular, it’s ruined his curveball.

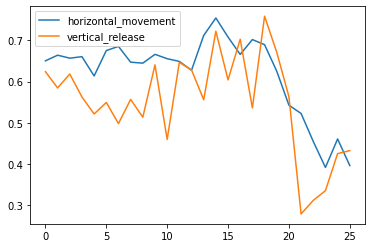

Courtesy of Jeff Nicholas, a two-game rolling graph of Snell’s vertical release point and the horizontal movement of his curveball:

The label on the y-axis isn’t entirely clear, but this graph shows that as time has passed, Snell’s release point has fallen off a cliff, and his curveball has gotten sweepier and sweepier with it. Whereas it used to get six inches of horizontal movement, it’s averaging about a foot of horizontal movement this year. Despite perfect spin mirroring between his fastball and curveball, this change has been devastating for both his fastball and curveball.

I’ll be honest, I’m still not entirely sure what the issue is. If it was clearer what it was, Snell would probably still look like a Cy Young pitcher. It feels undeniable that dropping his arm slot is the culprit behind his relative downfall. But it feels just as useful to answer why.

His fastball characteristics have mostly remained. He’s retained his fastball ride and velocity, and he’s locating it in the same general location as before. And yet it’s gone from a pitch with a .362 xwOBAcon in 2018 and 2019 to a .565 xwOBAcon in 2020 and 2021. Maybe the reason that he got away with having a straight fastball was because of his curveball. That sure seems to be the case.

Snell’s 2018 and 2019 curveball location versus his 2020 and 2021 curveball location:

This is pretty damning. In previous years, Snell most often dropped his curveball right below the zone. Since 2020, there are three collections of pitches. One high, just off the plate to his arm-side. One low, in the bottom, arm-side quadrant of the strike zone. Another below the plate, spread out beneath the zone. Snell’s not pitching to his most optimal spot anymore, and that’s probably because the command of his curveball has worsened with his new arm slot.

If he doesn’t have his curveball, then Snell is right to shift to his slider as his main secondary offering. He’s making do with what he’s got. The issue is that his slider is a low-30s CSW pitch, while his curveball is hovering around 40% CSW when it’s at its best. An added bonus is that Snell’s curveball hardly ever gets put in play. That still remains true, but now his curveball CSW is in the low-30s with his fastball and slider, and his fastball is getting decimated.

Even though Snell still does well in the way of spin mirroring, I think he was better off before. It’s easy to say that in hindsight. He had three velocity bands, and he still does, but aside from the inability to command his curveball, I think he lost something else in the process too.

From 2018 to 2019, he had the fastball come in at 95-96 mph. Omitting his changeup, his slider came in around 88 mph, with five inches of glove-side movement. Then there was his curveball, which came in softer at 81 mph, and with six inches of glove-side movement. Now that he’s widened the gap in horizontal movement and velocity between his curveball and slider, I think they’ve lost their symbiotic relationship. And the same goes for his fastball and curveball.

The easy solution is to revert to his old arm slot. That should fix his command and movement woes. But clearly it’s not that simple! Snell had surgery in 2019 to clean up loose bodies in his elbow. He returned in September — and he still had his trusty old arm slot — but something happened that offseason. Maybe it’s a compensation thing to avoid future injury. Maybe not. Whatever the case, it seems clear that Blake Snell is at his best when he’s throwing over the top. And for now, he’s not doing that.

Photo by Larry Radloff/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

This post was a bit poorly timed ?

Articles that age poorly for $100, Ken

Lol