You probably don’t think of Brady Singer as having much in common with Joe Ryan and Bryce Miller. Aside from them all being right-handed, in their mid-20s, and still working to deliver on their prospect promise, the similarities appear to end.

Singer operates with a throwback sinker-slider combination that has changed very little in his five MLB seasons. Ryan and Miller are the opposite. They are both four-seam fastball-forward and seemingly always tinkering with pitching lab-created secondary pitches that have garnered them a lot of attention in the fantasy baseball community on social media.

In 2024, Ryan and Miller have again tweaked their arsenals with the addition of sinkers and splitters. This time, Singer has joined them by adding some high four-seamers to his repertoire. While those adjustments might not appear to have much in common, the reasons behind them are very similar. For Singer, it might just be the key to unlocking his next level.

Four-Seamers vs. Sinkers

To understand why Ryan, Miller, and Singer pursued the adjustments they have, we need to examine some recent history of fastball pitch-type trends.

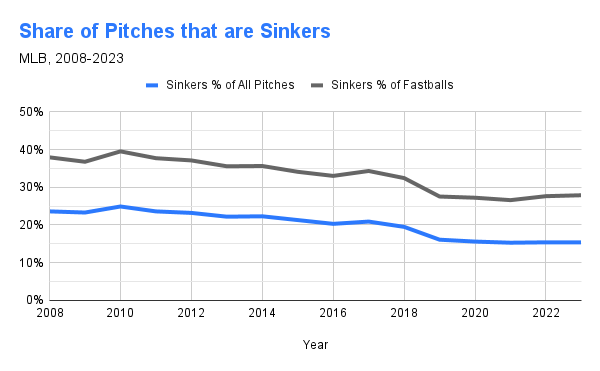

You’re likely aware that sinkers have steadily fallen out of favor in the Statcast era. Long gone are the days of the early 2010s when the Pirates and Cardinals threw lots of low sinkers to get hitters to beat ground balls into the teeth of shifted infields.

In 2010, just under a quarter (24.9%) of all pitches, and 39.5% of all fastballs thrown in MLB, were sinkers. By 2021, those same measures were down to 15.3% and 26.6%, respectively.

Data courtesy of Baseball Savant

Statcast showed us that four-seamers, especially those that were elevated with high spin rates, led to more swings and misses (read: fewer balls in play that could become hits) and teams and pitchers responded accordingly.

Soon, we were making fun of teams, like the Pirates and Cardinals, who were stubbornly hanging on to their sinker-heavy, weak contact-inducing ways instead of modernizing their approach.

Statcast also helped optimize the sinkers that remained to perform better. Primarily, that meant limiting their use to same-handed (i.e., right-on-right or left-on-left) opponents, as Justin Choi and Ben Clemens showed. Our Cam Levy went further and illustrated that not all sinkers are created equal, and the ones that have lots of horizontal movement were especially vulnerable to platoon effects, while those that were more vertically oriented were not.

Pitchers also started throwing their sinkers much faster. The average velocity of a 2010 sinker was 91.1 mph. By 2021, it was 93.0. That tracks with the overall increase in fastball velocity that occurred over the same period, but Choi pointed out that the share of sinkers that surpassed 95 mph quadrupled, while four-seamers’ share merely doubled.

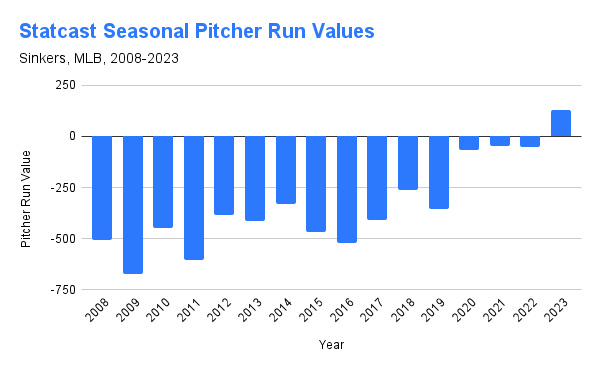

As Mike Petriello pointed out last winter, more powerful sinkers, more optimally deployed, led to the pitch type performing significantly better. After improving to almost neutral in 2020, sinkers in 2023 were net positive by pitcher run value for the first time in the pitch-tracking era (since 2008).

Data courtesy of Baseball Savant

At the same time, batters have started to catch up to the high four-seamers that have been all the rage. Hitters produced .309 wOBA against them last season, the best seasonal mark since 2017. The whiff rate against high fastballs, which had increased nearly every season since 2008 before topping out above 26% in 2020, has declined slightly in each of the past three seasons. Choi explored that too and suggested hitters were beginning to adapt their swings to their new fastball diet with better training techniques and technology, as Zach Crizer and Hannah Keyser illustrated.

Cat and Mouse

Warren Spahn once said, “Hitting is timing and pitching is upsetting timing.” Pitchers have several options at their disposal to upset timing. They can change speeds, which might be the first thing you thought of when you read the above. They can alter their pitch movements. And they can vary their locations.

Hitters are constantly seeking ways to narrow down what they need to look for. That gives pitchers a big potential advantage if they can force hitters to defend against a larger set of options.

As hitters have started to demonstrate they’ve caught on to the high heat, several four-seam heavy pitchers, like Ryan and Miller, and also front-line guys like Shohei Ohtani, are making opponents cover more of the strike zone by adding in the occasional sinker, especially against right-handed hitters.

If hitters know to look for the elevated, riding fastball from a pitcher, the sinker gives that pitcher a counter punch that comes from the same slot and release, but with a different movement profile and location. That might be just enough to get a pitch off a barrel for weak contact or to give the hitter pause enough to take a called strike. Either way… it’s “advantage, pitcher.”

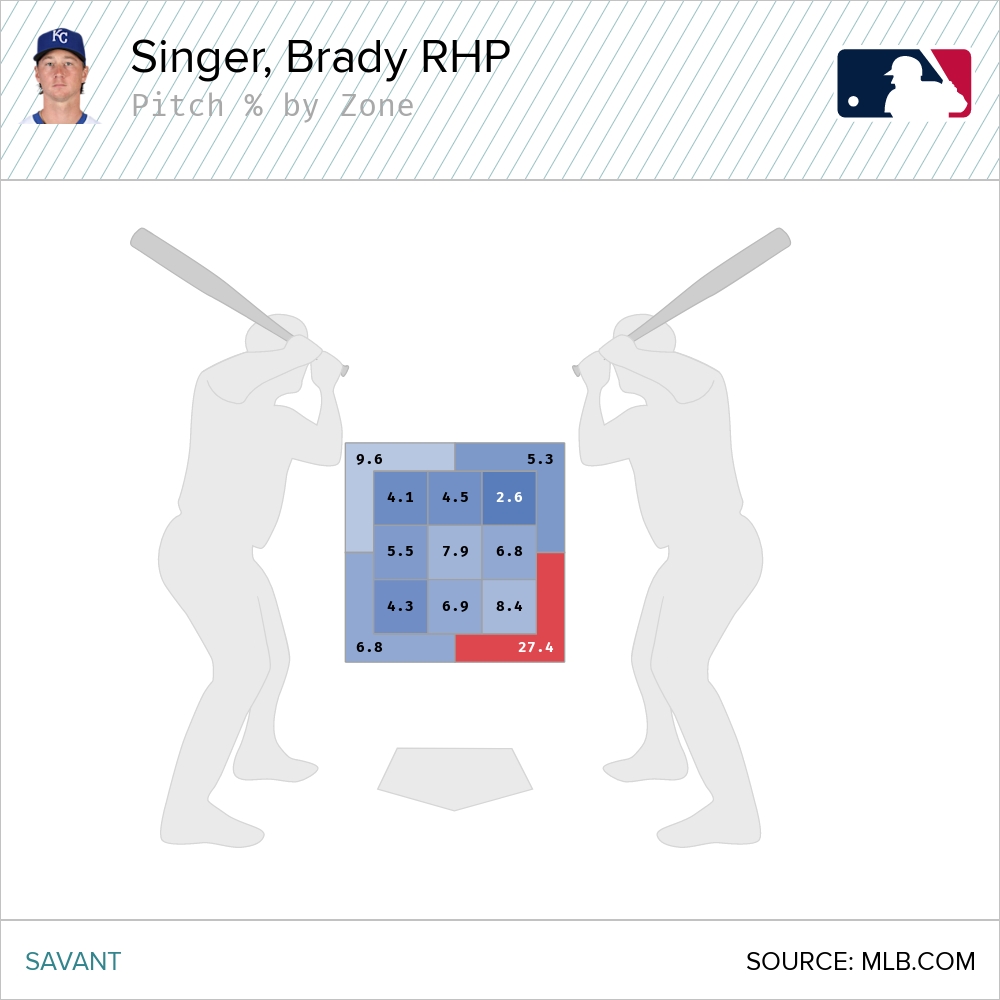

That same concept applies to Singer but in reverse. Everyone knows he’s been a sinker-slider guy who’s largely worked down in the zone. Before this season (2024), Singer had thrown a sinker or a slider for a whopping 93.7% of his career pitches. Against right-handed hitters, that share has been 98.8% (!). The large majority of the remainder, to hitters of either hand, were below-average changeups.

Not only could hitters trust they were going to get one of those two pitches, but they could also have a pretty good idea of where to look for them. Singer has varied his locations arm-side and glove slide with both the sinker and slider, but nearly three-quarters (73.9%) of his career offerings have been located in the mid and lower parts of the zone, with about half of those targeting the lower, glove-side corner:

Coming off the worst season of his career last season — 5.52 ERA, 18.9% strikeout rate, 48.6% hard-hit rate (1st percentile) — where he worked down in the zone more frequently than ever before (79.3%) and saw his sinker produce -12 runs and get pummeled to a .420 wOBA, Singer clearly needed a counter-punch to keep hitters from sitting on predictable pitch types and locations.

Just like Miller and Ryan needed sinkers to move hitters off the top of the zone, Singer needed to use a four-seamer to get hitters off the bottom.

Elevating Singer

He showed that new offering in Spring Training, and has carried that into his first six starts of 2024. After throwing just 32 total four-seamers in the first four seasons of his career, he’s now thrown 79 of them this season, for about 15% of his total pitches. Moreover, he’s deploying that new fastball variant much higher in the zone than his sinker — 2.73 feet on average, against 2.21 feet for the sinker.

Singer has been openly stubborn about sticking with adjustments in the past, instead choosing to rely on his strengths. But last season’s results seem to have created the necessary burning platform for him to adopt and stay with some changes.

When approached in Spring Training about why he was willing to adjust now, Singer was pointed, saying, “Probably sucking. Probably that, yeah.”

“It’s a different look for the hitters,” Singer said. “They can look horizontal with the slider and the sinker. Now being able to look up and down the zone, you change your eye level more. It’s going to be huge.”

Because of Singer’s tendency for supination, he’s not likely to be able to throw one of those high-spin, vertical-breaking four-seamers that rise above bats. That the velocity, spin rate, and movement on his four-seamer all rank below average, and the public-facing stuff models don’t love it, either, are evidence of that point.

But, he doesn’t need the four-seamer to be that anyways. He just needs to use it to threaten the upper regions of the strike zone a handful of times per game. And the initial results are promising.

It’s Working

Thus far, opposing hitters are 2-13 in at-bats ending on Singer’s four-seamer, and it’s generated a whiff 19% of the time opponents have swung at it. In a vacuum, that’s not particularly impressive, but it’s notably above the 10-12% whiff rates he typically gets on his sinker and his rarely-used changeup. The .286 expected wOBA against Singer’s four-seamers is the best mark of any pitch in his arsenal this season. In terms of run value, it’s been perfectly neutral, 0.0.

To illustrate how trusting the four-seamer up can help Singer, let’s look at a key at-bat against the Astros on April 11. Jose Altuve had led off the game by jumping on a first-pitch, low-and-inside sinker and smacking it for a double. That forced Singer to face the fearsome Yordan Alvarez with a runner in scoring position right away.

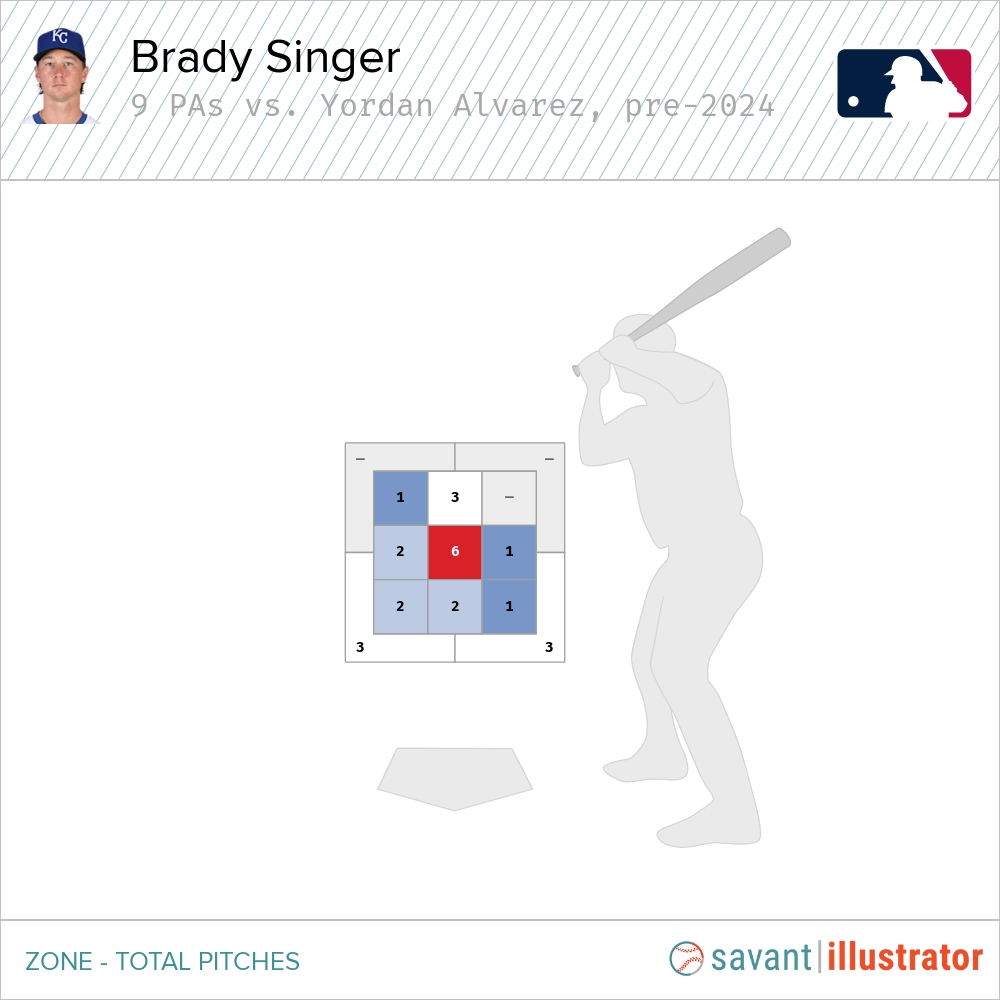

You can see in the clip above how Singer approached that daunting situation — he started Alvarez off with a four-seamer up and in, which Alvarez fouled away. Singer had faced Alvarez nine times previously in his career and never before had thrown a pitch to him near that part of the strike zone, as you can see below:

Only four of the 24 pitches he’d thrown to Alvarez in those previous face-offs had been up. This time, with the four-seamer in play, he threw another one ahead 0-1! It badly missed the strike zone, but that’s not critical to the point. What mattered is that he’d shown Alvarez that he’d attack him up. That helped set up the next two sliders down that got Alvarez to swing over the top and punch out.

Singer eventually escaped that threat without letting Altuve score and went on to give up a single run in 5 innings of work that day, one of four starts this season where he’s allowed a single run or less.

What It Means

It’s easy to cherry-pick a specific example that fits the through-line of this piece, but that doesn’t change the fact that Singer has implemented an important tweak that seems to be helping his whole arsenal. Through six starts, Singer’s trademark sinker is the 9th-most valuable pitch in the league with +5.8 runs. It’s in the same range as the four-seamers of Hunter Greene and teammate Cole Ragans. In addition, Singer’s ground ball rate is a career-best 57%, and he’s boosted his strikeout rate back up to a league average-ish 24.5%.

There’s likely some regression coming when his .209 BABIP and 86% strand rate correct. His 9.4% walk rate is also slightly elevated from his career norms. But, there’s enough to like about the approach change to believe he can sustain the strikeouts and tamp the free passes back down. Those won’t make Singer a front-of-the-rotation pitcher but will help him pitch around league average, which will go a long way toward keeping the hot-starting (and fun to watch) Royals in contention this summer.

More broadly, Singer’s adjustments (and Ryan’s and Miller’s) are good reflections of how hitters and pitchers interact and influence each other. We had a long period of low-and-away that hitters eventually adapted to. Then we had a (shorter) period of rise-and-ride. Hitters figured out how to adapt to that, too. Now pitchers are moving on to combined strategies which will test hitters in additional, less predictable ways. As Eno Sarris put it last fall, maybe the next period will be “everything, everywhere, all at once.” We’ll see how hitters adapt to that.

Photos courtesy of Unsplash and IconSportswire | Designed by Aaron Asbury (@aarongifs on Instagram)