You almost surely know the Lucas Giolito story by now. The White Sox right-hander rode a mechanical and approach overhaul – dramatically shortening his arm action, scrapping his sinker, and leaning into changeups and sliders – to become one of the most effective starters in baseball. Those changes yielded much more deception, a simplified arsenal that played above the sum of its parts, and many more strikes and strikeouts. For three seasons, 2019-2021, Giolito ranked 13th among qualified pitchers in innings pitched (427.2), 18th in ERA (3.47), 16th in FIP (3.54), 6th in strikeout rate (30.7%), and tied with Shane Bieber for 7th in fWAR (11.3).

Lucas Giolito, 93mph Fastball and 82mph Changeup, Overlay pic.twitter.com/hOcrr1eT09

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) May 5, 2022

Last year, however, was a different story. Giolito came into the season about 20 pounds heavier thanks to some off-season lower half strength building and then dealt with a collection of illnesses (COVID) and nagging injuries (abdominal strain) while posting an unsightly 4.90 ERA.

Despite the time missed, Giolito still worked 161 innings and was worth 1.8 fWAR thanks mainly to that volume. His strikeout (25.4%) and walk (8.7%) rates each moved in the wrong direction and opponents hit .270 against him, about 65 points better than they had the prior three seasons.

Poor Luck & Bad Defense?

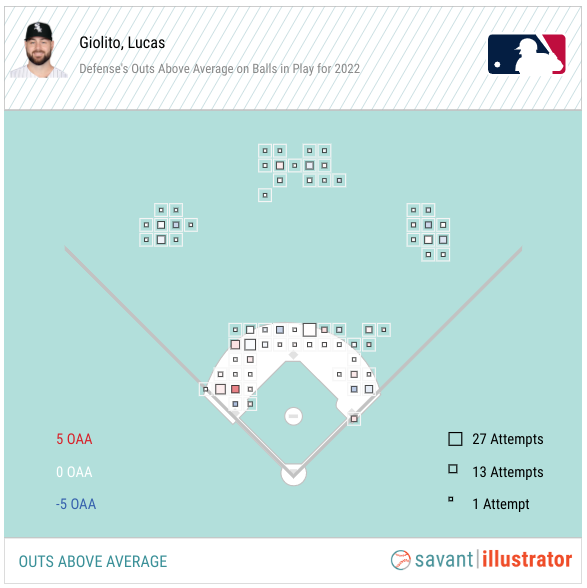

On the one hand, you can argue that batted ball fortune and the White Sox’ 24th-ranked team defense (by OAA) deserve a large fraction of the blame for Giolito’s rough go. He suffered from a .340 batting average on balls in play (BABIP), 81 points worse than the .269 BABIP he’d enjoyed previously. The White Sox produced -3 OAA as a team when Giolito was on the bump and much of that was in the outfield (-5 OAA behind Giolito), which combines poorly with Giolito’s well-above-average fly ball tendencies (28.7% fly ball rate).

Giolito’s run prevention estimators suggest he was unfortunate. His FIP was 4.06, his xERA was 4.23, and his SIERA was 3.79. Similarly, his expected batting average, expected slugging, and expected weighted on-base average allowed were all markedly better than his actual results.

But, on the other hand, the bad defense and poor BABIP luck do not do much to explain the lost strikeouts and increased walks. And, despite the peripherals outperforming the results, each of the underlying marks I called out above was elevated meaningfully from his prior norms.

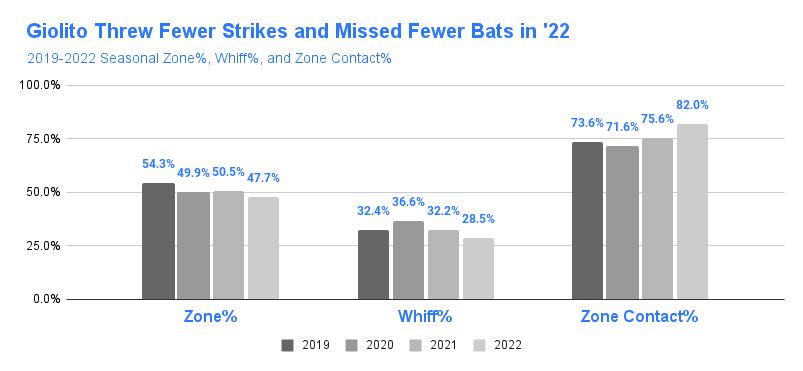

While he might not have pitched as poorly as a 4.90 ERA might suggest, it also seems clear that something changed to make Giolito’s zone rate drop to 47.7%, his whiff rate decline to 28.5%, and his in-zone contact rate shoot up to 82.5%, after they previously sat north of 50% (zone), 32% (whiff) and below 76% (zone contact), respectively, since his 2019 breakout.

Get A Grip

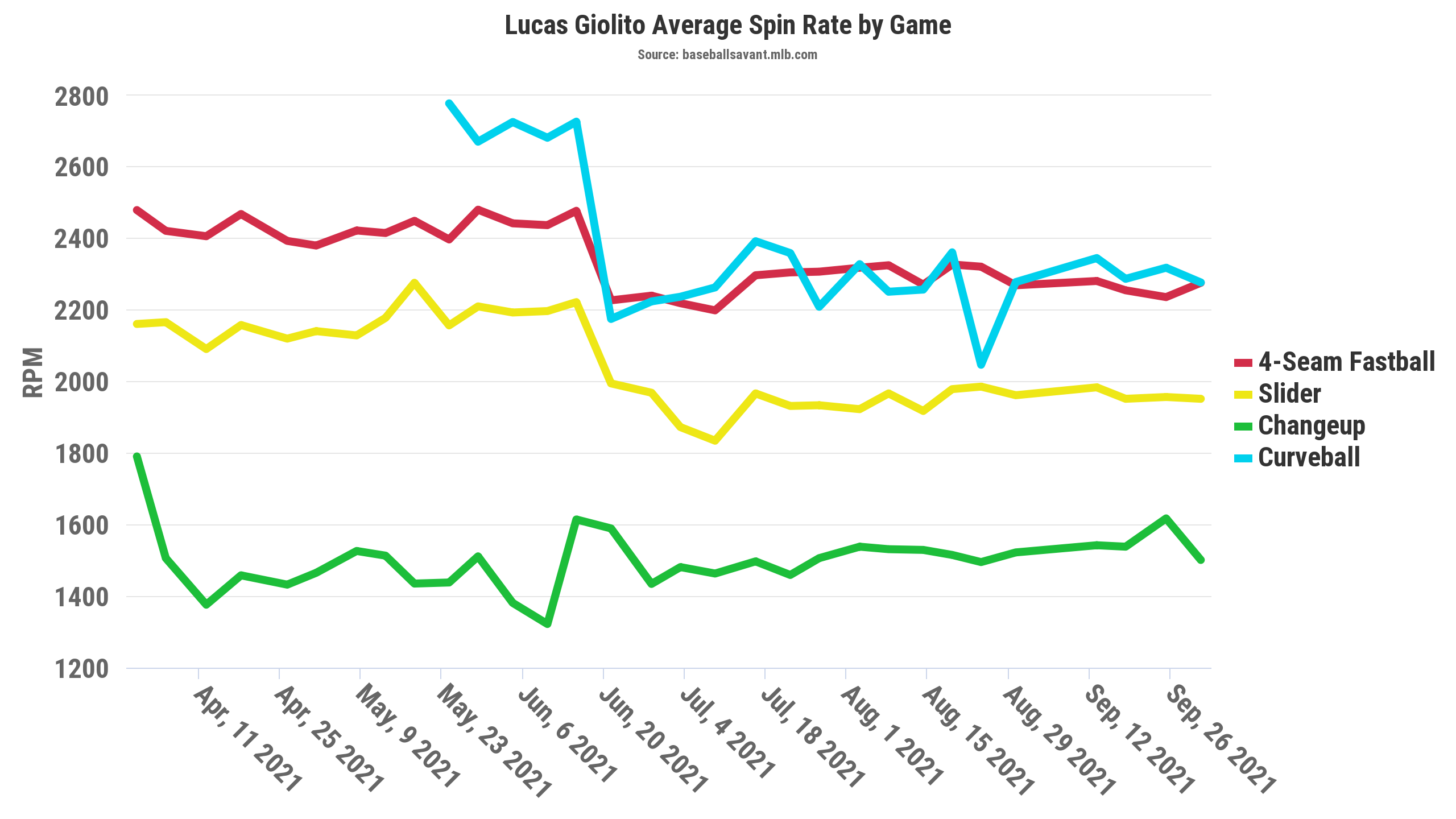

Naturally, it’s easy to point to (and many have) the 2021 mid-season sticky stuff ban as a culprit for diminishing Giolito’s stuff. Josh Donaldson tried to make Giolito one of the sticky stuff poster boys and the data bears out that Giolito lost a lot of spin after enforcement ramped up in June 2021.

He lost about 250 RPMs on his four-seamer and slider, and about 450 RPMs on his more sparingly used curveball last season, and his spin rates nominally stayed in those same lower ranges in 2022.

That said, Giolito pitched quite well in the second half of 2021 – 2.65 ERA, 3.50 FIP, and .263 wOBA allowed. In fact, his second-half results were noticeably better than his first-half 4.15 ERA, 4.00 FIP, and .307 wOBA allowed.

As you would guess from the lost spin, though, he did miss fewer bats. His second-half strikeout rate in 2021 was 25.8%, more in line with the depressed mark he generated in 2022. He compensated for the lost punchouts with fewer walks (6.4%) and some good batted ball and sequencing fortune, evidenced by a .247 BABIP and an 83.6% left-on-base rate in the second half.

You might assume that the loss of spin made Giolito’s high four-seamer play down, but the Statcast data indicates that he recovered most, if not all, of the pitch’s vertical movement after a short post-ban adjustment period. On that point, the whiff rate on Giolito’s four-seamer was greater in each of July, August, and September/October than it was in April, May, and June of 2021.

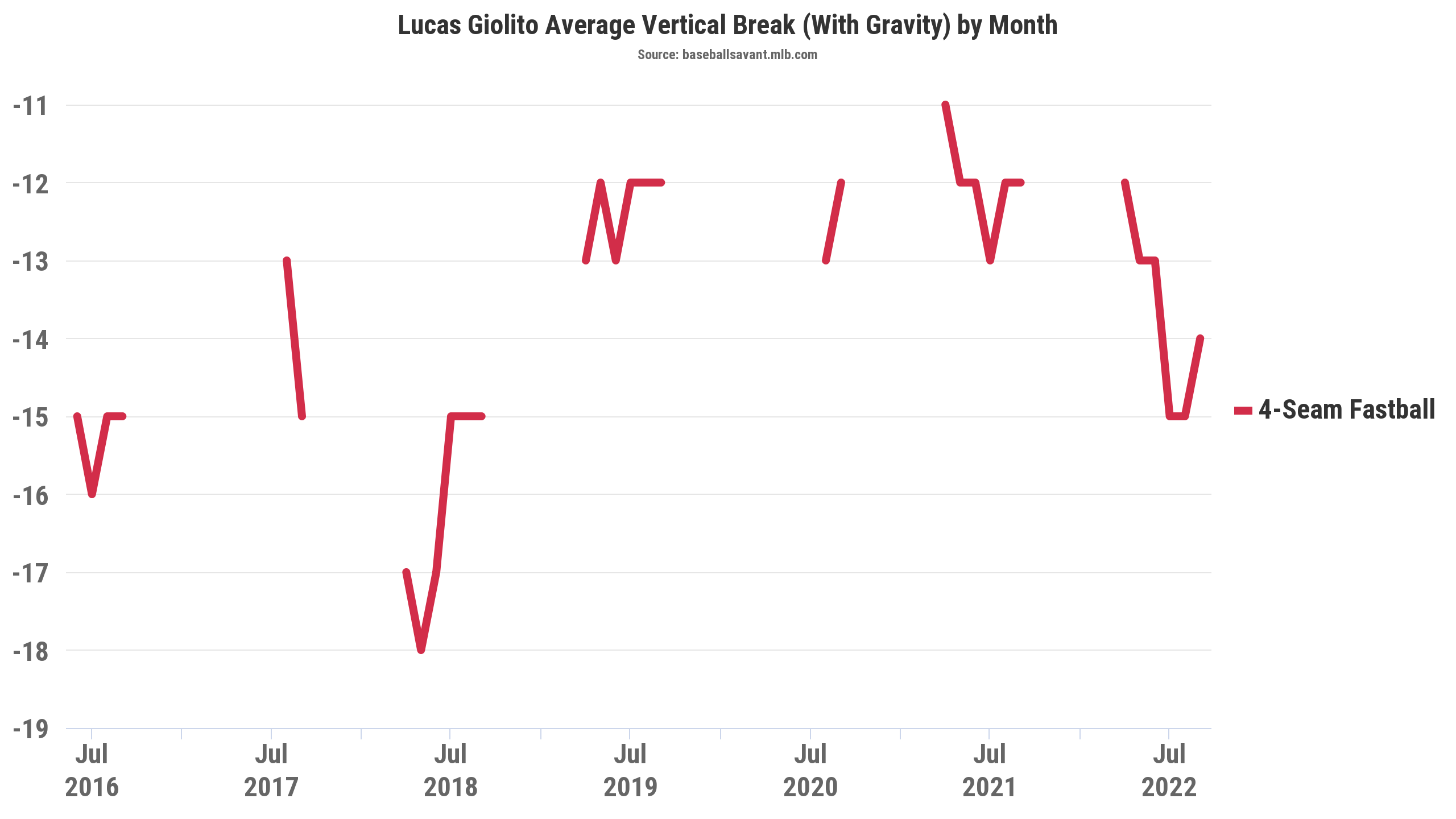

This season started similarly, with his four-seamer averaging around -12 inches of vertical movement and 36.4% whiffs in April, but that changed as the season progressed. Giolito’s four-seamer lost ride and had more downward vertical movement than it had at any point since 2019:

That suddenly steeper fastball also came with diminished velocity, too. After averaging around 94 MPH the prior three seasons, Giolito averaged 92.6 MPH with his fastball last year. As a result of the new, sub-optimal movement profile and lower velocity, Giolito’s four-seamer performed much worse than it had previously:

Don’t Forget the Secondaries

For all the negative profile changes of the fastball, it still was a nearly neutral offering by Statcast run values. The same cannot be said for his changeup and slider, which were also not immune to unwanted changes.

Both his changeup and slider have thrived in his reinvention, not because they were big movement, bend-the-laws-of-physics offerings but because of their exceptional deception. Both pitch types have been consistently below average in terms of horizontal and vertical movement by Statcast’s measurements but his total arsenal was a hitter’s nightmare in large part because of how well his offspeed pitches tunneled with his fastball out of his short arm action delivery.

That seemingly changed last season when the performance of both his changeup and slider changed drastically for the worse:

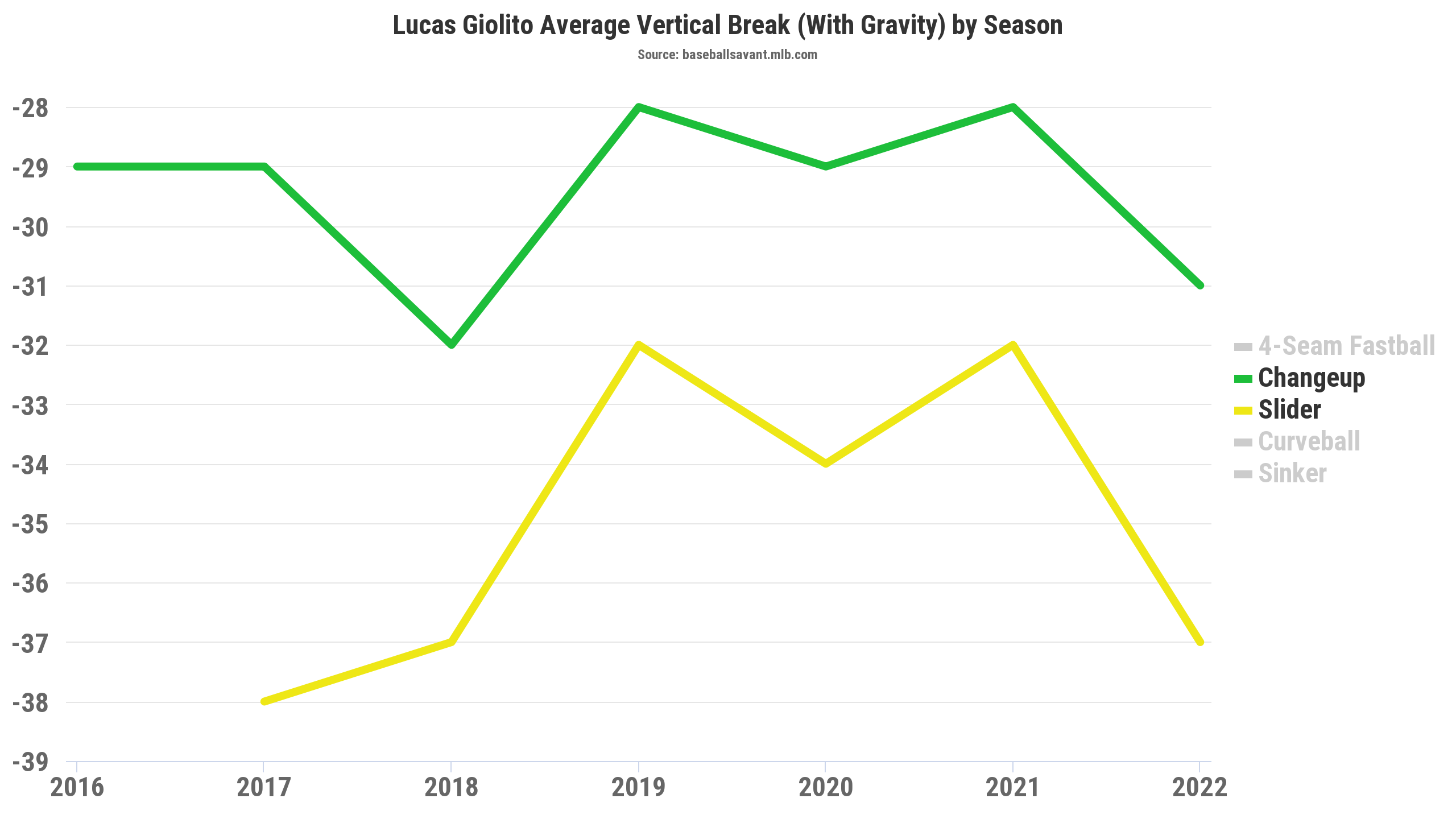

You could attribute a fair share of this change to the fastball being less fearsome and making it easier for hitters to stay back and deal with the secondaries. But it could also be, at least in part, because of significant shape changes with the changeup and the slider. Like the fastball above, both of Giolito’s main secondaries started getting a lot more downward movement last season.

As a result, Giolito’s slider got far fewer swings and misses and more of his changeups ended up going for balls than previously had. Just 40.6% of his changeups were thrown in the strike zone, compared to 50.8%, 44.6%, and 60.8% in the previous three seasons. Taken together with the fastball changes it all compounded to make Giolito less deceptive and it easier for hitters to discern ball from strike and make contact.

Going Forward

Rather than it being one clear issue to blame, it seems Giolito dealt with a number of seemingly smaller things – perhaps the early season core injury, the COVID illness, the new bulk on his frame, or the changed ability to grip the ball, or some combination thereof – that resulted in subtle mechanical tweaks that decreased the quality of his stuff, reduced the deception in his delivery, and broke down how well his pitches tunneled together.

He discussed openly during the season how he was searching for answers. “It’s kind of like a little bit of a mystery,” said Giolito in September. “We just looked at some video and saw some stuff in my upper body. When I’m throwing harder, I’m staying back longer and I’m holding the ball and it unloads late. Whereas now it’s kind of separated. I’m unloading before I should be, which I think leads to inconsistencies with velocity as well as commanding the baseball.”

Giolito recently suggested to James Fegan of The Athletic that he’s found answers thanks to an offseason biomechanical analysis. Giolito said he and his personal team saw a host of spots in his delivery where his body was “not firing correctly.”

Now that he has an entire offseason to tweak and train, overhauling his faults has his full focus. The 28-year-old right-hander also said he’s already back to his normal playing weight and is focusing more on fluid movement than heavy lifting.

That news should give heart to White Sox fans hoping their erstwhile ace can turn it around and raise concern for rivals who have to face him next year. After all, the last time he dedicated an offseason to revamping his mechanics to optimize his arsenal, he turned himself into one of the best pitchers in baseball.

Photo by Nick Wosika/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

Banger piece man ?