James Bell sat behind a long podium at the Dapper Dan luncheon one January afternoon in 1976. Besides him that cool winter day were Joe Morgan, Ralph Kiner, Luis Tiant, and others all being inducted into the Pittsburgh Sports Hall of Fame as a celebration of their prowess on the diamond. The former ballplayer – approaching 80 years old at the time – smiled with his famously white teeth (he once turned down a contract because instead of a per diem on travel, the owner offered free dental services. Bell said he didn’t need to fix what didn’t need fixing, turned around and went home) and made small talk with those around him.

Morgan and Tiant happily signed autographs for the wide-eyed kids that ran up to the stage thrilled to be meeting their sports heroes, all trying to get just a small piece of these larger than life figures. When the kids got to Bell, a Negro League legend from decades prior, he was quick to reach into a bag and hand them a paper with his autographed already jolted down in green ink. A nerve disorder that made the Hall of Famer shake in his later years made it a mystery when he’d have any kind of dexterity. “I always try to take a few minutes and get some autographs ready just in case…” he explained to them.

James Bell didn’t have sympathy for his now slow movements, he was thrilled to flash that smile and talk about what he loved almost more than anything, baseball. And he talked to those kids and journalists around him because they all wanted to know – how fast was he?

He was fast. So very fast.

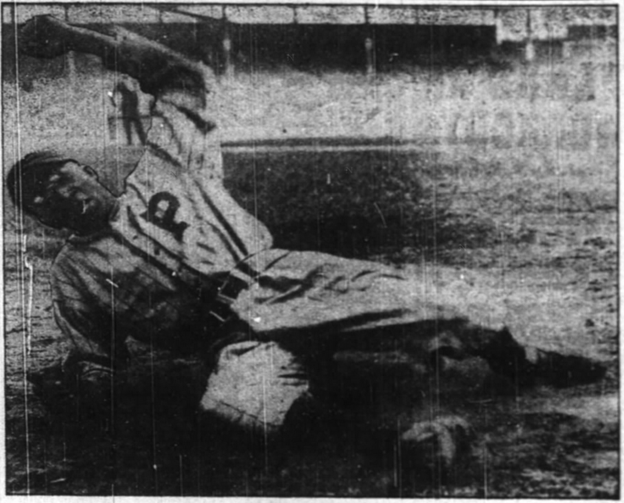

Cool Papa Bell in 1937, the Quad City Times

On a exhibition against Major Leaguers in 1945, Bell ran from first to home on a sacrifice bunt. He had a big lead on the base, and when the bunt went down the third base line he bolted with his usual impossible speed to second. As he got to the base standing up, he noticed the third baseman has charged the ball to throw the batter out, so Bell darted to third. On his way over, he saw Boston Red Sox catcher Roy Partee “went down the line to cover third and I just came on home past him.”

Cool Papa Bell they called him. He earned that nickname as a fresh 19 year old on the St. Louis Stars – the youngest player on the team. Bell was rail thin when he was brought to the team. Rail thin. He came onto the team just shy of six feet tall and 135 pounds soaking wet. But the young man was clearly something special. Bell had played semi-professional ball on and off for a few seasons and figured it was about time to leave the game behind to find himself a steady job. That plan was quickly nixed. “…the East St. Louis Cubs needed a pitcher to throw against the old St. Louis Stars of the Negro League,” Bell said, “and they asked me to come out for just one game.” He impressed The Stars so much that they immediately offered the young man a contract to play for the big club as a two-way player, playing the field with dazzling speed and taking the mound early and often.

In his first professional season in 1922, Bell took the mound one game against the Chicago Black Giants. The Giants were led by Oscar Charleston a man who hit .409 that season, walloped an untold hundreds of home runs in his career, and is still widely considered to be one of the greatest ballplayers of all time.

The 19-year-old Bell couldn’t exactly throw heat at the best of times, and for most of his career his throwing arm would be considered his only weakness, but he wasn’t a power pitcher. He was a junk baller who with two strikes was confident as anyone. “If I got two strikes on you, I could throw my knuckle ball and it would just do this dart-down. I bet you I could strike anybody out with that knuckle ball.” He got two strikes on Charleston and – with the poise of a ageless veteran – threw that knuckler that darted right down for strike three. (The only batter he couldn’t throw his knuckleball by, he said, was his sister.)

He was so calm under pressure that day that teammates started calling the young man “Cool”. St. Louis Manager Bill Gatewood added a twist of dignity befit the youngster with “Papa”.

At nineteen years old Cool Papa Bell was born.

He put up respectable numbers as a pitcher – getting 18 recorded wins over two seasons – but his blazing speed and dazzling fielding made him impossible not to play everyday, and by his age 21-season Cool Papa Bell was officially off to the races. He led his league in stolen bases nearly every season and was consistently among the league leaders in walks. Pitchers were constantly looking over their shoulder at Bell. Just the way he liked it.

“If a pitcher ever got two balls on me,” he said, “I was sure to get a walk or a hit. Why? Because I could foul off every pitch that was questionable. It wasn’t unusual for me to foul off 15, maybe 20 pitches in one time at bat.”

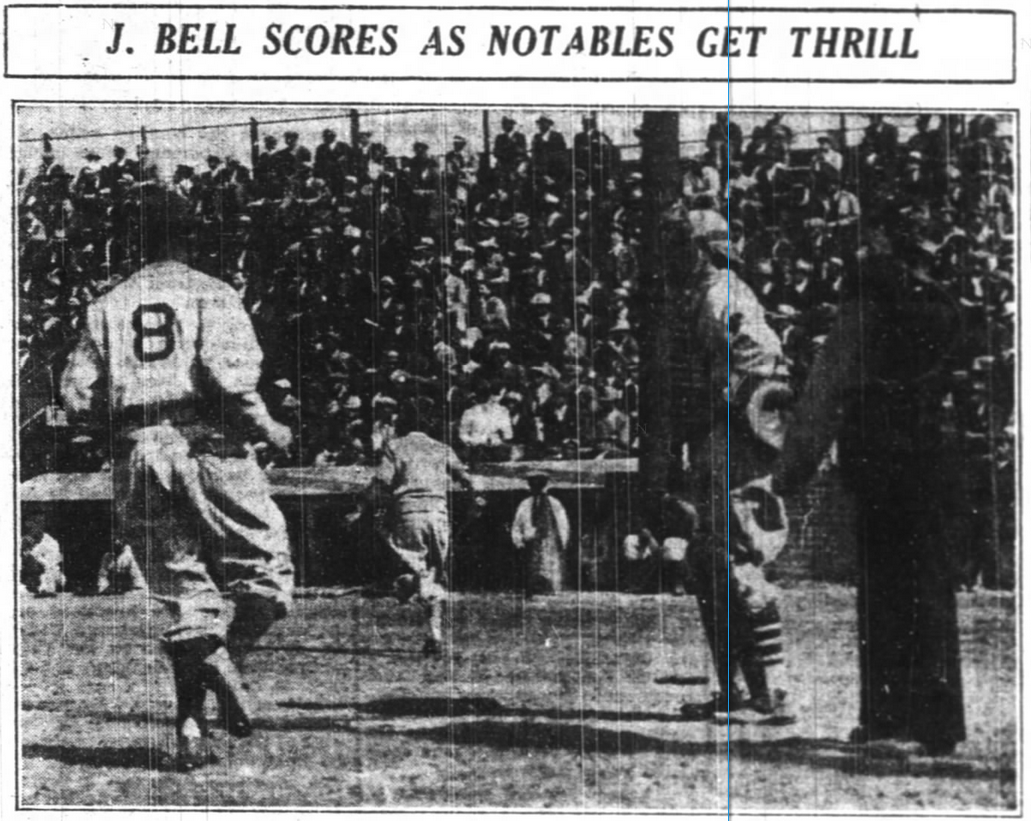

James “Cool Papa” Bell crossing home against the New York Cubans, 1935, from the Pittsburgh Courier

The 1933 season saw Bell with the Pittsburgh Crawfords – his fifth official Negro League team (he made annual stops in the Cuban and Mexican leagues during the winter months for a total of nine clubs in his career). These Crawfords were an absolute squad. Oscar Charleston put together his last truly great season, Josh Gibson led the league in home runs in only his rookie year, Judy Johnson continued tearing up the league, Cool Papa Bell hit .372 and stole a career high 175 bases. One-hundred seventy-five bases. Then for good measure the team had Satchel Page at his peak both on the mound and spinning tall tales.

After a road-trip where Cool Papa Bell racked up a number of stolen bases Paige said of his roommate, “Bell was so fast he could flip off the light and get into bed before the light went out.”

Cool Papa Bell laughed at the absurdness of the story years later. Only, he said, it was true. In one of the many highly questionable hotels Negro League players were allowed to stay at, Bell found that the only light switch had a short that caused about a three second delay. When Paige eventually got back to their shared room he plopped himself in bed exhausted, heard the switch being flipped, felt Bell jump in his own bed, then the lights went out.

He was so fast.

Bill Veeck, owner of the White Sox who would sign Larry Doby as the first African American ballplayer in the American League and a year later sign a 42-year-old Satchel Paige to a Major League contract, stood by the dugout one dizzly afternoon watching Bell run the bases. With the infield dirt on the wrong side of dry and a breeze flapping his jersey, Veeck clocked Bell around the bases at 13.1 seconds. The world record was 13.3. “Cool Papa was one of the most magical players I’ve ever seen.” Veeck later said. Sometimes legends become so entrenched by evidence that cold hard facts supplant wild stories and grains of salt are tossed aside.

Cool Papa Bell was so fast that Jessie Owens, the gold medal hero of the 1935 Olympics, refused to race him. Bell was for real.

In the late 19th century, baseball journalists called Cool Papa Bell’s type of player (if there was such a thing then) “scientific”. In today’s game, they may call speedsters that scan the field as “high IQ players”. Cool Papa Bell called his brand of play “tricky ball.”

Cool Papa Bell on the 1936 Pittsburgh Crawfords, from the Pittsburgh Courier

“They use to bat in a run on a base on balls.” Bell said in an interview with the American Heritage History Magazine, “If they had a man on third and the batter walked, he’d just trot down easy-like down to first and the man on third would just sort of stand there, looking at the stands. At the last minute the batter would cut for second as fast as he could go. The could would yell, ‘Hey! Look at that!’ The pitcher would whirl around, the guy on third would light out for home, and like as not they wouldn’t get anybody out.” Like the story about scoring from first on a sacrifice bunt or consistently beating out two hoppers to the second baseman, Cool Papa Bell loved the game and played hard.

In 46 recorded games against white Major League All-Stars, the center fielder hit .395 with four home runs and let it be known Negro League players were among the best of the best. Bill Veeck said Cool Papa Bell was an equal fielder to Tris Speaker, Joe DiMaggio, and Willie Mays. The difference was DiMaggio was making $65,000 and Bell was lucky to make $450 per month in the best of years. Often times especially during the depression the paychecks were late, diminished, or came in a different form than money.

“So many people say I was born too early;” Bell said, “but that’s not true, they opened the doors too late.”

Bell has only 285 official stolen bases. Even with the inclusion of seven Negro Leagues into Major League Baseball record books earlier this year, so many of his and his contemporary’s games simply weren’t scored. Bell tells a story of going 5-5 with 5 stolen bases one game but no one was around to keep score that day.

The St. Louis Browns reached out to Bell in the twilight of his career after Jackie broke the color barrier to see if he was interested in trying out for the team, but this was 1948 and Bell was pushing 45 years old. “People told me I should have tried for a job with the Browns just for the money, but I couldn’t do it just for a paycheck. I never had any money so I never worried about it. I just didn’t want the fans to boo me and if I played at that age they sure would have.”

“Sometimes pride is more important than money.”

From 1922 through 1947, through three different decades, nine teams, hundreds of teammates, and thousands of rickety bus rides, Cool Papa Bell made himself one of the best ballplayers of all time. But as late as 1970, it was doubted he would ever get into Cooperstown since he never played in the Major Leagues despite his legendary status. Bell worked as a janitor a few years after retiring – finally getting that steady job he talked about as a nineteen year old – and became a night watchman for the St. Louis City Hall after that and waited for the call. He lived on Cool Papa Bell avenue in St. Louis with his wife of over sixty-years (Clarabell abbreviated her name as Clara B. Bell to avoid the awkward alliteration), helped Jackie Robinson learn second base, and became a sort of mentor to Major Leaguers like Ken Griffey Sr.

Finally, the Baseball Hall of Fame called his name in 1974. His plaque in Cooperstown reads:

Combined speed, daring and batting skill to rank among best players in Negro Leagues. Contemporaries rated him fastest man on base paths. Hit over .300 regularly, topping .400 on occasion. Played 29 summers and 21 winters of professional baseball.

Two years later, Cool Papa Bell got to tell those kids at the Dapper Dan luncheon he was the fastest there was.

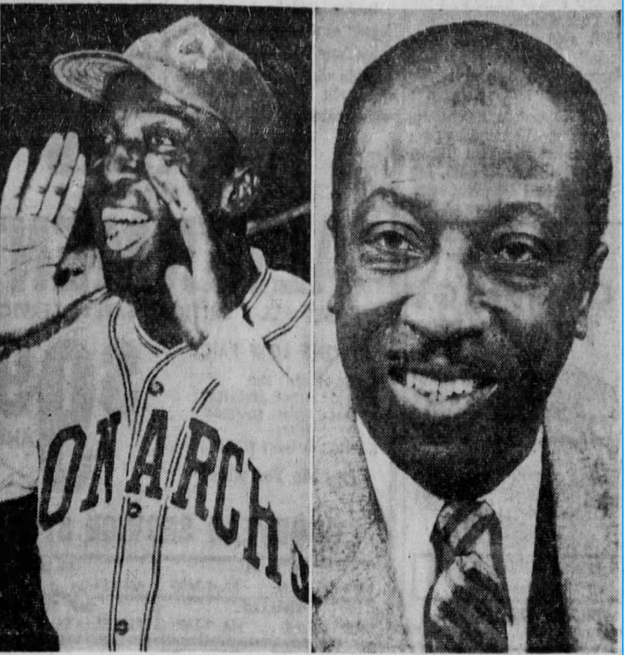

Bell as the manager of the Kansas City Monarchs (left) and as a night watchman in St. Louis City Hall after retirement (right). 1963, The St. Louis Dispatch

Photo by Johannes Plenio/Unsplash | Adapted by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)