Cold openings are hard right now. In a moment I’ll talk about how Dallas Keuchel is doing his his thing for the White Sox in a very new and interesting way, but I don’t feel like I can do so without acknowledging the absurdity of baseball and sports under COVID-19 and the surrounding circumstances. On-field action aside, the virus has sent multiple St. Louis Cardinals employees to the emergency room. Johan Maya, a scout for the Arizona Diamondbacks, lost his life to the disease at age 40. These things didn’t need to happen for baseball. And while the social tumult of late May and June may have died down for some, my community still undergoes violent trauma on a daily basis, and the cries for help are churning as loud as ever. I love watching baseball and writing about baseball, but given current events, I can’t do either right now without a pit in my stomach, and I hope we can all acknowledge and agree that the necessary catharsis baseball brings to us does not displace conversations about what really matters. It’s hard to write much without making that understanding clear.

Now to the action! Let’s talk Keuchel. He’s scheduled to make his fourth start for the Pale Hose on Monday evening, and he’s delivered everything to them as promised through three of them, allowing just five runs over 17.2 innings. His control has been pinpoint, walking just two during that frame, and while his 11 strikeouts in the same span (15.5% K rate) are disconcerting, they also belie a 24.8% overall whiff rate that would stand as one of the best of his career.

That last part is a little eye-catching, since Keuchel’s already diminutive velocity has continued to fall through the basement this year. His fastball wouldn’t even get pulled over on the highway in some states — at an average of 87 mph, it’s one of the five or so slowest sinkers in the game. Slow fastballs aren’t exactly a recipe for big-league success, so it may be unsurprising to learn that Keuchel has decreased his fastball usage more than almost any starter this year this side of Zack Godley, throwing sinkers and four-seamers just under 35% of the time, more than 20% lower than his career rates. Might as well keep the hitter guessing if you can’t throw hard, right?

Keuchel’s Pitch Mix: Requiem for a Sinker

I’ll speak to that later on, but let’s take a moment to give Keuchel’s sinker its deserved requiem before we talk about what’s replacing it. It ordinarily wouldn’t be a big adjustment. In a vacuum, it feels logical to not rely on a 87 mph fastball almost half the time. In this case, it feels as if Kareem Abdul-Jabbar woke up one morning in 1982 and decided that the hook shot had served its purpose for him. Sinkers are out of vogue, but Keuchel’s wasn’t just any old two-seamer. By linear weights, which measure how much each individual pitch changes the likelihood of a run scoring, only Jake Arrieta and Zack Britton have gotten more bang out of the sinker than Keuchel since 2014. If you prefer rate stats, only Britton, David Price, Johnny Cueto, Craig Stammen, and Jeurys Familia have allowed a lower Weighted On-Base Average (wOBA) on the pitch.

All that’s to say that despite being slow and being a sinker, Keuchel’s has been the best of the best for most of the 2010s, and now, it’s mostly out the window. Through those three starts in 2020, the sinker appears to have moved into a timeshare with the cutter and changeup for the crafty lefty’s dominant offering:

(Source: Baseball Savant)

Disclaimer: No, I don’t know why Keuchel’s primary fastball was reclassified as a sinker for this season after being a two-seamer for his entire career prior. There’s a lot of goofy stuff happening with the switch over from Trackman to Hawkeye. It doesn’t really matter much.

Regardless, that’s a pretty radical change in game plan! Two offerings that barely constituted a third of Keuchel’s pitches in 2019 are now being used more than everything else combined. It’s actually not totally new to this season. When Tony Wolfe checked in on Keuchel towards the end of his tenure with the Braves last September, he took note of his expanded cutter use. It was a puzzling development at the time, because as Wolfe correctly pointed out, it simply was not a very good pitch.

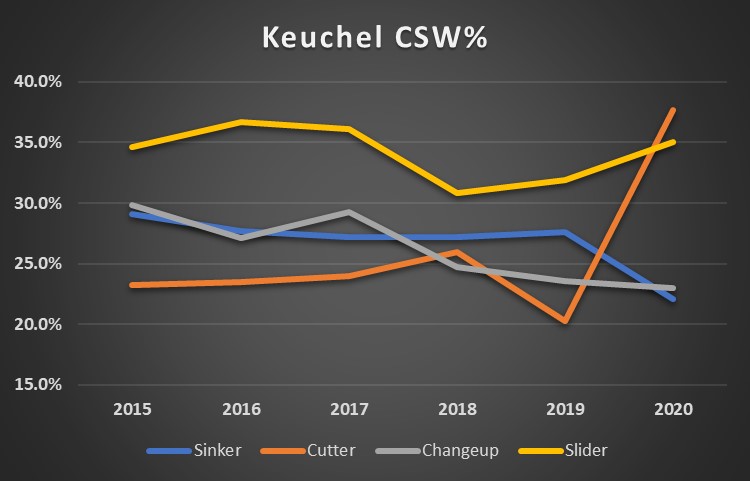

The story is different this time around, though. Not only has the cutter suddenly become Keuchel’s primary offering, it’s been a really good pitch. By Called Strikes + Whiffs Rate (CSW%, read more about why it’s a great stat here), the cutter has thus far overtaken Keuchel’s long-effective slider as his single most dangerous pitch:

(Source: Baseball Savant)

Once again, that’s a big bump we’ve got on our hands! Not only is that really good for Keuchel, it’s really good, period: Among starters, only Wade LeBlanc, Tyler Chatwood, and Not Justin Bieber have posted a better CSW mark on their cutter this season. In most circumstances, there’s a logical progression of variables we can look at to try to solve the mystery of a suddenly-nasty pitch. But nothing about the cutter’s movement profile is particularly different than in years past:

| Year | Velo (mph) | H-Mov (in.) | V-Mov (in.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 85.4 | 31.4 | 1.2 |

| 2016 | 85.8 | 31 | 2.5 |

| 2017 | 86.7 | 28.8 | 4.7 |

| 2018 | 86.4 | 30.2 | 3.6 |

| 2019 | 86.1 | 30 | 2.4 |

| 2020 | 85 | 29.9 | 2.4 |

(Source: Baseball Savant)

Nor has the way he locates it changed significantly over the past couple years, with 2020 on the right here:

(Source: Fangraphs)

It was the same story with the changeup, and it was rather baffling. I looked just about everywhere for the key to this pitch mix, and found almost nothing. Count leverage was a dud, as the pitch selection shift has been so radical that no single situation is illuminating its logic. Platoon splits tell us little more. He’s throwing the cutter to same-handed hitters for the first time in his career, giving 22 of them already to lefties after just 33 in total from 2015-19. It’s a nice new wrinkle to his game, but just a small part of it. It doesn’t do too much to explain either it or the changeup’s big spike in whiff rate and decreased contact quality.

What’s the Catch?

So here we have two pitches that seem to be characteristically identical to what they’ve already been for several years, yet they’re seeing big upticks in performance seemingly solely by virtue of being used more. Is it possible that Keuchel’s just gotten very lucky early in the year?

Definitely. It’s almost always very possible. Any Keuchel success is going to have luck involved. That’s just the nature of the game with a fastball that barely brushes 90 on the best of days. This time, however, it appears he’s mostly earned his 2.55 ERA. The stingy control mentioned earlier has been enough to offset the continual drying-up of strikeouts, and his resulting 2.83 FIP and 3.41 xFIP are more than respectable. By Statcast metrics, he’s been as good as of late as he was coming off a Cy Young: early returns on his hard hit rate (29.2%) and expected wOBA (.297) would be among the best of his career over a full season.

What are we missing? There’s something at play here that isn’t being properly quantified. As is often the case when the numbers send us in circles, its time to check the video! Having watched the majority of the pitches Keuchel has thrown in a White Sox uniform, I can confirm that this August 5th at-bat against Milwaukee’s Jedd Gyorko is a good enough representation of what a typical battle between hitter and Keuchel has looked like in 2020 First, he falls behind 1-0 on a cutter that grazes the top of the zone but misses the spot:

Next, he throws a changeup that starts on the outskirts of the zone but never gets particularly close:

2-0 to Jedd Gyorko in a one-run ballgame isn’t an ideal circumstance. Gyorko has some thump in his bat, and he hits lefties a lot better than righties. He’s got a .418 career batting average against them in 2-0 counts. This is his spot.

So what does Keuchel do? Right back to the cutter for strike one:

Anything flying through the top of the zone at 84 mph is liable to be a sketchy proposition, but it’s not a bad pitch here. Gyorko doesn’t read it super well, and ultimately decides (correctly) that it’s not worth swinging at in a hitter’s count. What Keuchel gave him on a 2-1 count, however, was a pretty bad pitch:

Oh dear. That’s another cutter at 84 mph, but right down the middle and fatter than a goose egg. Call me a hater, but Gyorko definitely should not be flinching at that one. He’d probably agree, as the at-bat ended soon thereafter on a next-pitch sinker:

Also not the greatest of spots, but even if it catches a bit too much plate, there are far worse things than a front-door sinker that the hitter swings right over. But it’s hard to not keep going back to that 2-1 cutter that he completely got away with.

It’s just one pitch in one at-bat over the course of a long (if far shorter than usual) season, of course. But there’s still something unsettling about it, from a hitting perspective. In a hitter’s count with a favorable platoon matchup and a one-run deficit, Gyorko had every reason to load up and try to make it a two-score game. He hadn’t yet taken a cut during the at-bat, and it was the fifth time he had seen the cutter during the game. But after getting caught lunging at a changeup to end his previous plate appearance, he simply could not pull the trigger on the best pitch to hit he’d get all day.

How does that happen? There’s clearly something about that cutter that was keeping Gyorko uncertain enough to render his bat harmless. You watch enough sequences like that one, and you’ll start to wonder if there’s something in the pitch mix itself that keeps hitters off-balance. It’s quite possible that despite being utterly pedestrian on their own, the sinker-cutter-cambio troika works together in a way that makes them much tougher to hit in juxtaposition. Deception and crafty pitching are always the name of the game for a soft-tosser like Keuchel, but how do we measure it?

Into the Tunnel

One way we can look at it is through the lens of pitch tunneling, on which Baseball Prospectus keeps some rather cumbersome leaderboards. At its simplest, tunneling is this Pitching Ninja overlay:

Shane Bieber, Fastball & Cutter, Overlay.

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 10, 2020

Bieber does an incredible job of making the fastball and cutter appear to follow the same path, all the way until they don’t. That’s pitch tunneling. It’s how much a pitcher can make each one of their offerings look like the other for as long as possible — how much each pitch comes flying out of the same “tunnel,” so to speak. Michael Augustine had a great writeup of the concept on this very site last year!

You can find BP’s full explanation for how they do it here. In short, using pitch data and scientific research on exactly at what point mid-pitch a hitter has to commit to swinging or not, the folks at BP determined exactly how many inches apart a given pair of pitches typically is at three distinct points in the pitch’s flight. First, you have the distance between two pitches at their release point (Release Distance), at the hitter’s commit point (PreTunnel Max Distance), and when they crossed the plate (Plate Distance). In theory, a pair of pitches that tunnel well will have minimal distance between them at the first two points before diverging greatly by the time they cross the plate. BP measures this using PrePlateRatio, which is simply the plate distance divided by the commit-point distance.

Again, a pitcher with Keuchel’s low velocity needs to keep hitters guessing as long as possible. By 2019 pitch tunneling measurements (2020 has yet to be made available), his new sinker-cutter-changeup arsenal does exactly that. I looked at tunneling data for each of his primary four pitches, taking weighted averages of the distances between each pair — that is, each combination of sinker/slider, sinker/cutter, cutter/changeup, etc. when thrown back-to-back — and I found that Keuchel’s tunnels are below-average to average almost entirely across the board, except for one specific pitch pair. Turns out, he’s pretty good at making his cutter look like a changeup and vice-versa (all measurements in inches):

| Pitcher | RelDist | PreMax | PlateDist | PlatePreRatio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| League | 2.67 | 1.69 | 21.48 | 12.99 |

| Keuchel | 4.45 | 1.42 | 25.00 | 17.63 |

(Source: Baseball Prospectus)

There are some interesting twists to that data. A pitch’s physical location is just one of several cues a hitter picks up when identifying a pitch. This doesn’t take important things like spin and arm speed into account. Here, you might also notice that despite the cutter and changeup typically being much tighter than average at the commit point (good!) and further apart than average at the plate (also good!), they’re also starting out much further apart from each other than is normal. That isn’t a good thing — a widely inconsistent release point pretty much defeats the purpose of a good tunnel before it even comes into play.

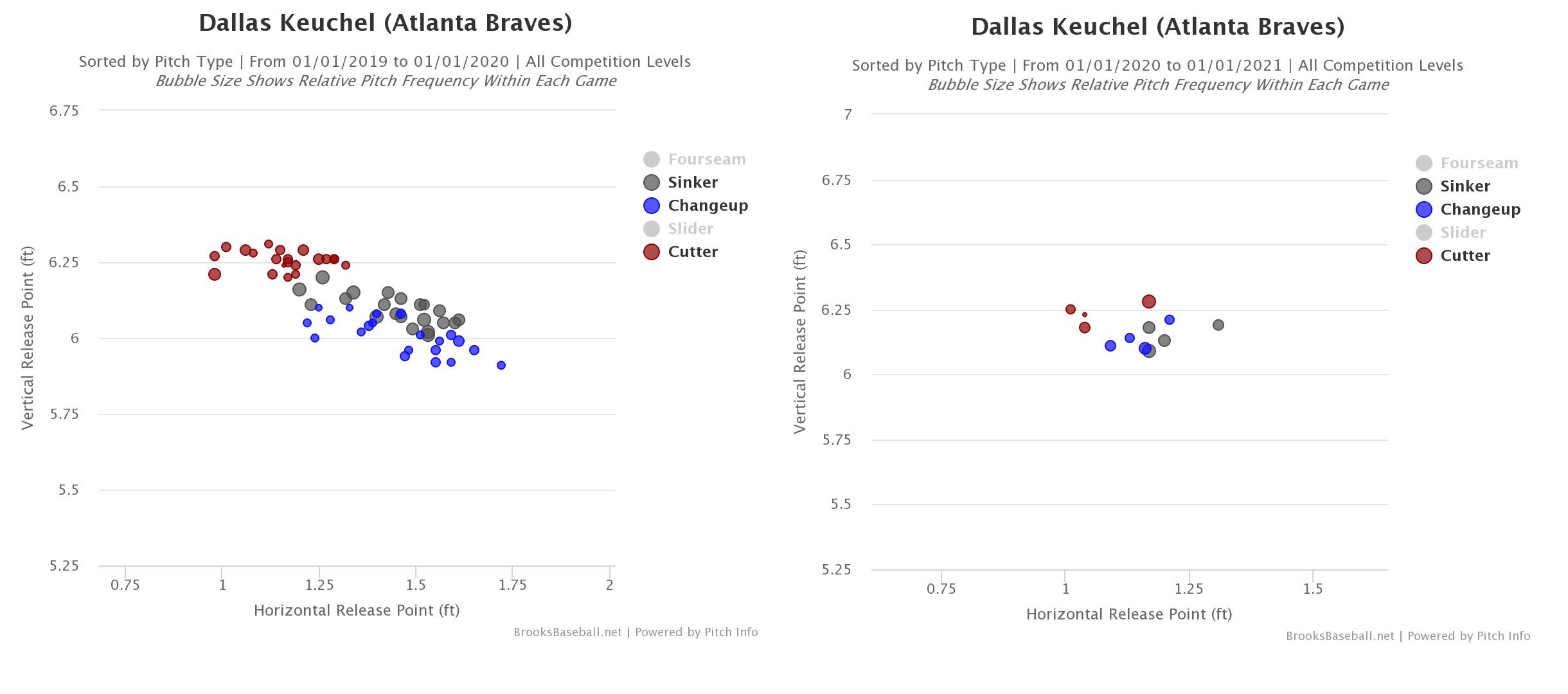

But it’s also something Keuchel may have already fixed. Take a look at his sinker, cutter, and changeup release points last year compared to the current campaign:

(Source: Brooks Baseball)

Why it still has him playing for the Braves I don’t know, but his release points is clearly much tighter than it was a year ago. The blue and red circles on the left barely ever even come close to each other, but the intermingling on the right looks much more promising. In theory, this could be working in tandem with the tunnel already present in Keuchel’s cutter/changeup mix to make them even deceptive and tougher to hit solidly than in the past.

I might also be totally off-base! Depending on the trajectory of the pitches, it’s entirely possible that a closer release point will actually lead to more distance between the pitches at the commit point, would would totally throw our hypothesis here into the deep blue sea. Only time will tell! Or at least, the eventual release of 2020 pitch tunneling data will. Anyway, enjoy Keuchel making Keston Hiura — an outstanding hitter! — look a bit silly by busting him inside with the cutter before mercilessly pulling the string on a changeup.

Out of the Tunnel

Even for a great sinker like the one Keuchel has featured for most of the past decade, 87 mph is simply too slow to be a viable primary weapon. Unless you’re Kyle Hendricks, but we can’t all be blessed with surgical, witch doctor-esque command. For Keuchel, it’s probably actually been true for a couple years now; 2017 was the last time we saw him truly resemble a top-of-the-rotation starter anyway. He’s just now adjusting his approach accordingly and using what was his A-pitch as a change-of-pace offering to keep hitters from timing up his other stuff. That other stuff is pretty tough to square up when it’s used right!

Tonight, Keuchel makes his fourth start of the year against a surprisingly competitive Detroit offense. He still probably won’t be missing many bats, but I’ll be keeping an eye on how he’s using those off-speed pitches. He’s still the same big-bearded, soft-tossing, grounder-happy Dallas Keuchel — he’s just finding new ways to be the best possible version of that Dallas Keuchel.

Photo by Zach Bolinger/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

I picked him up today dropping Chatwood and hoping for a good stream against Detriot. Fingers crossed. So it was cool to see this article come out. I’ll likely be dropping him after tonight and picking up Turnbull — even though I don’t like the matchup with Clevland coming up.