David Price has always done whatever he can to help his team win games. The former number one pick came up in 2008 and got the final outs of a tight Game 7 in the American League Championship Series, only a year after he was drafted out of Vanderbilt University. In subsequent seasons, the left-hander evolved into the dominant starter befitting of his draft selection, including winning the 2012 AL Cy Young.

When he found himself in Boston after signing a high-priced free-agent contract, Price had elbow troubles in 2017 and moved to the bullpen to be there for his team. A year later, Price started and ended up being the leading force behind the Red Sox’s fourth title of the century.

It should then be no surprise that the southpaw told Dodgers manager Dave Roberts in the spring that he’d be fine in the bullpen, to which he started the season—and he’s done well to this point, pitching to a 3.23 ERA (3.69 FIP/ 3.93 xERA). But with the Dodgers’ rotation now in flux, Price is now being stretched out again to be a workhorse every fifth day.

In Price’s first start of this season against the Diamondbacks a week ago, the left-hander pitched three scoreless innings but only struck out three batters against 15 batters faced. Amongst his 51 pitches thrown, Price had 12 called strikes—five of them on the sinker—while only generating four swinging strikes. This has been a larger concern for him this season, where he’s currently posting his lowest strikeout percentage since 2013 at 21.5%. While he’s throwing a career-low percentage of pitches in two-strike counts, which undoubtedly hurts his ability to strike out hitters, Price’s inability to garner whiffs from hitters consistently is why balls are put in play rather than racking up strikeouts.

For Price, his penchant for punchouts has been fulfilled by throwing his terrific changeup.

Price’s changeup has been a Money Pitch across all his offerings thrown in his career — for someone that’s pitched since 2008, that’s incredibly impressive. And with that pitch, it’s easy to see why the veteran southpaw has been so successful for as long as he has. But this season, the pitch has suffered across the board, with the biggest drop in its swinging strike percentage. The reason for that requires looking at a couple of things — what the pitch looks like and how it’s being used.

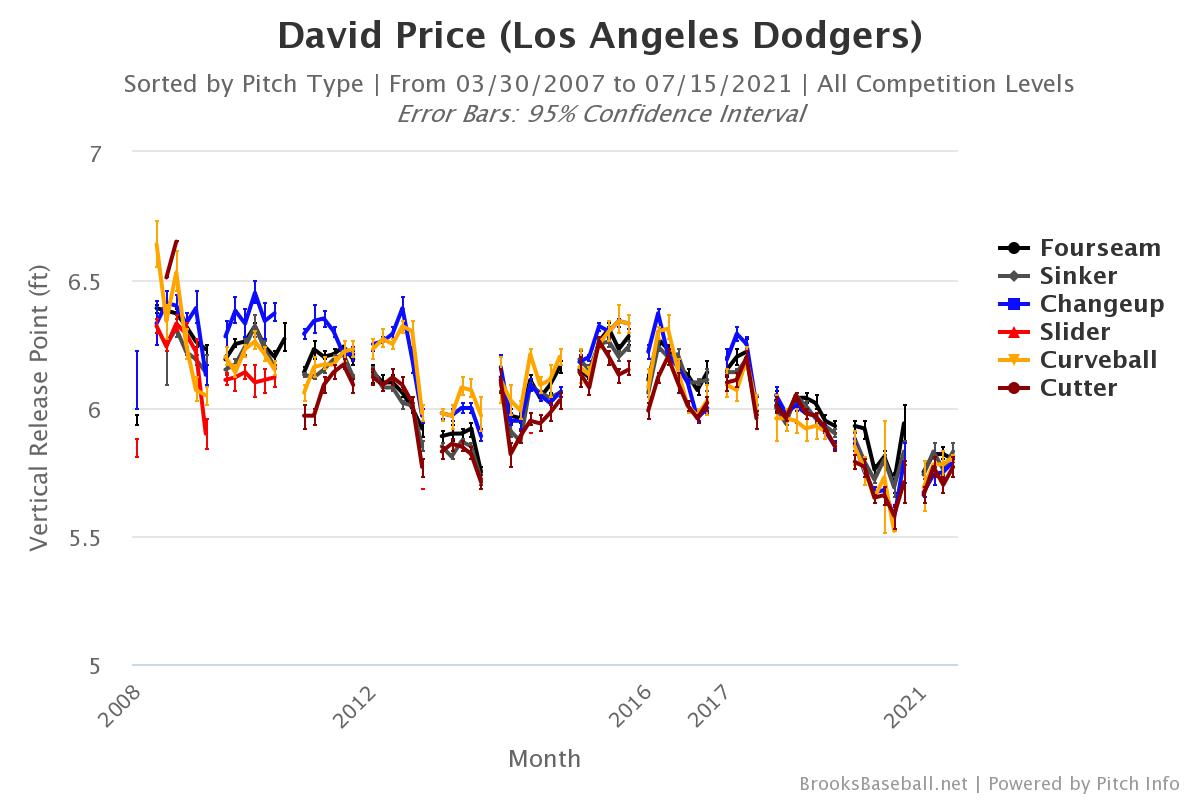

After not pitching last season, Price has endured some noticeable changes this season from 2019, particularly with his arm slot, which has dipped as the years have gone on.

Whether it’s been with age or just a change in philosophy, it’s undoubtedly changed his pitch arsenal.

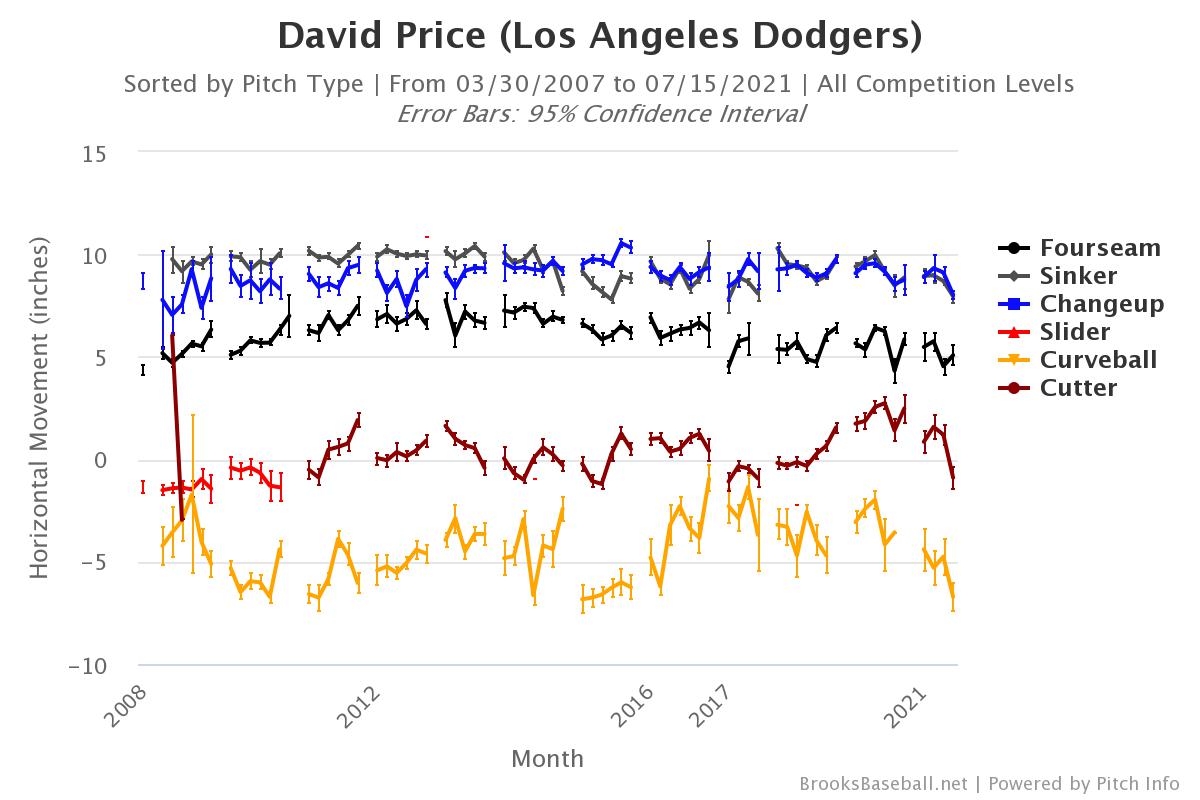

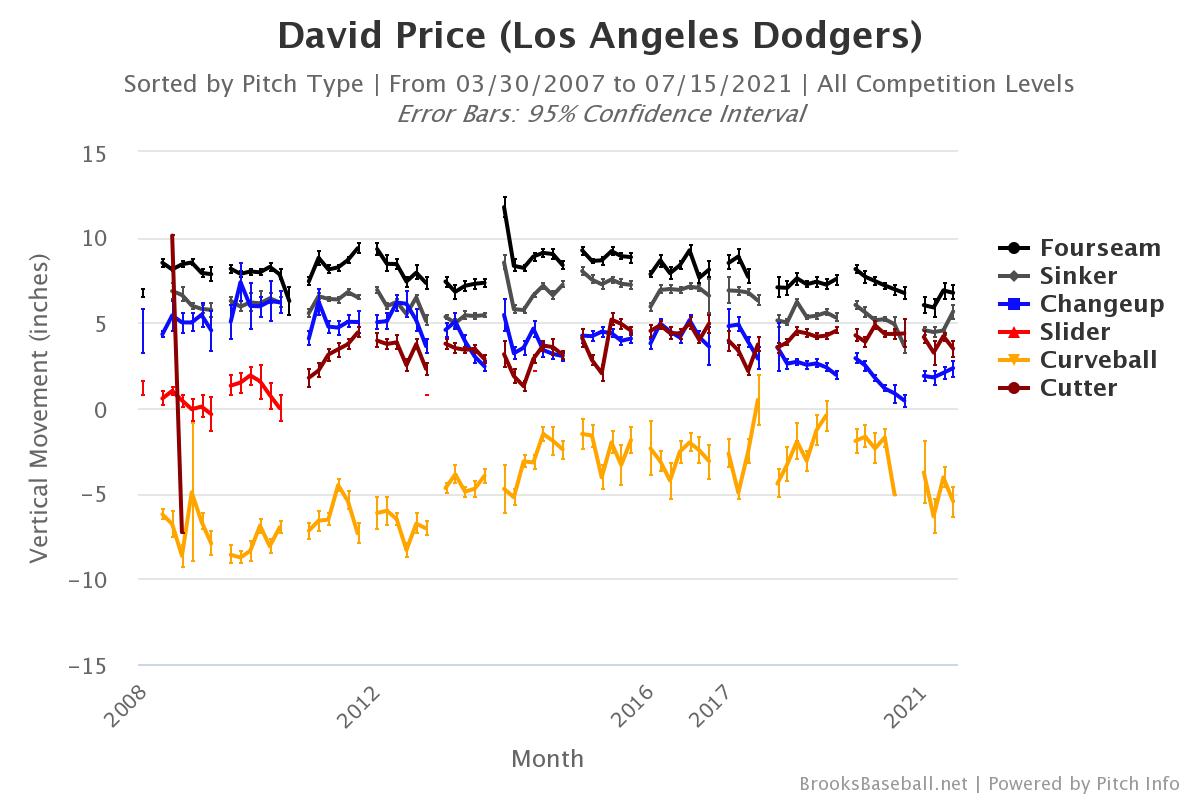

His pitches have generally lost vertical movement while maintaining relatively the same amount of horizontal movement as before. While losing vertical movement on the four-seamer is worrisome, the same can’t be said for the sinker, as having less upward force on the ball has helped Price keep the ball on the ground 58.5% of all batted balls against the pitch.

But, again, the strikeouts are what will make Price a dominant pitcher through the end of the year, which brings us back to the changeup. There has been a slight increase in vertical movement while keeping the same amount of arm side run as he’s always had. While not dropping the same amount as it had in the previous few seasons, it shouldn’t be enough to cut the whiffs so significantly. That’s where our next exercise comes into play.

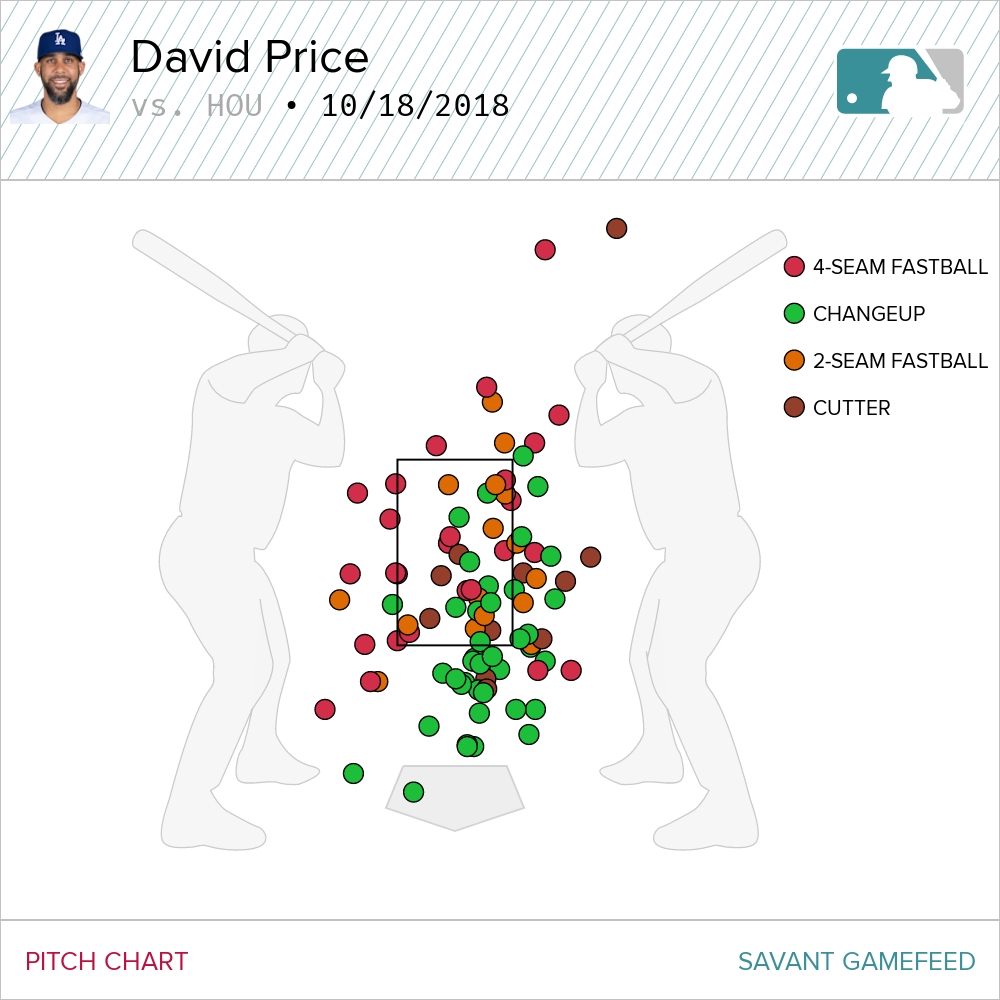

As a Red Sox fan, the most impressive start I ever saw Price pitch was Game 5 of the 2018 ALCS in Houston—his first win as a starter in the postseason. Striking out nine men across six scoreless frames was a superb effort given that the left-hander was not only working on short rest but threw in the bullpen the night before while dealing with his playoff demons. It was simply a superb performance and one that also highlights the importance of his changeup. The dominance of the pitch was on full display as Price used the offering 40 times in his 93 pitches, with 12 of those being swings and misses—especially considering he only got three whiffs on his other 53 pitches. Though, it wasn’t just the changeup that did the damage. Take a look at the pitch chart from that game.

There were many changeups down and arm side, which resulted from facing eight right-handed hitters that day, with Tony Kemp as the only lefty. But take a look at those fastballs on the other side of the plate. It’s a classic approach of hard in and soft away to retire hitters. The best example of this is an at-bat against George Springer in the first inning, resulting in a strikeout.

The first pitch here is a heater far inside that makes Springer move his feet.

https://gfycat.com/inexperiencedthirdhochstettersfrog

Price then follows it up with a changeup beneath the zone, but vertically down the middle so Springer thinks it’s a fastball when he commits to swinging.

https://gfycat.com/pleasingsizzlingkitten

Springer then chases a heater inside that seemingly has a bit of cut.

https://gfycat.com/regalleadingatlanticbluetang

So after working Springer inside again, this next pitch is supposed to be another changeup beneath the zone—the same as the second pitch. However, it’s too far beneath the zone and the hitter can lay off.

https://gfycat.com/imaginativerewardingafricanharrierhawk

This is where Boston’s battery thinks they’ve got Springer looking changeup, so they try to dot a four-seamer on the outside corner down and away but Price yanks the pitch inside resulting in a foul ball.

https://gfycat.com/appropriateweepyhusky

Working inside most of the at-bat, Springer now is looking inside, leaving himself vulnerable to any offering away from him. Cue the changeup.

https://gfycat.com/fearlesssomberapisdorsatalaboriosa

Notice how Springer’s feet are stuck in place, as his front foot refuses to move towards the pitch and forces him to reach for the pitch without a stable base. That is a byproduct of facing all those pitches inside, where the hitter couldn’t sit on the pitch away.

To further illustrate the point, just take this swing from Gary Sánchez in Game 2 of the 2018 ALDS, a couple of weeks before the at-bat we just discussed.

https://gfycat.com/coolacclaimedgrison

That is a well-executed cutter down and away, a pitch that certainly shouldn’t be hit out of the park—unless the hitter was looking for it. The pitch prior was also a cutter away, that was taken for a strike. The pitch before that was also meant to be away. Falling into this predictable pattern of going away from hitters has hurt Price during his career, making him far less effective.

To both left-handed and right-handed hitters, Price’s best seasons have come when he’s worked his fastballs—four-seamer, sinker, and cutter—inside (using the respective shadow and chase regions). Just as we saw in the Springer at-bat, working the hitter inside and making them conscious of that inner half makes them hesitant about pitches away from them. That split-second indecision is all Price needs for his changeup to clean up hitters. But this year, you can see the usages of the heater inside is at or near the bottom to both-handed hitters for his career and, similar to the trend we’ve expressed, has shown a middling number of swings and misses on his changeup.

Currently sporting a BABIP of .402, Price should be a reliable option for the Dodgers going down the stretch considering he’s only yielded a 4% Barrel/BBE and a nearly 52% groundball rate through the first half of this season. But to be more than just reliable and the force Los Angeles needs in lieu of Clayton Kershaw, working his fastballs inside will be key in helping play up his changeup and punch out more hitters.

Photo by Ric Tapia/Icon Sportswire | Design by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)

The NL west race will be close.