On Monday night, Albert Pujols suited up at Chavez Ravine for the Dodgers for the first time. The Machine went 1-for-4 with an RBI grounder and a strikeout. At 41 years old, it is very likely that this shot with LA represents the last hurrah for the future Hall of Famer. He isn’t expected to be much more than a complementary piece for the club, but it’ll be great to see him get a respectable shot at one final title (should he stick out the year with them).

Still – like a lot of people, the Angels’ release of Albert Pujols a few weeks back got me thinking. About his legendary career, yes, but also about the end. About when it’s worth raging against the dying of the light, and when it may be worth considering that good night. There’s a quote that one of my favourite (sorry) hockey players, Trevor Linden, once gave, that I think is really prescient here. I’m paraphrasing, but it goes something like: ‘When an athlete retires as 38 or 39, he retires an old man, but in the eyes of the rest of the world, he’s still a young man.’ Being in my mid-30’s, I think about this quote a lot. I don’t consider myself an old man, but were I an athlete, I’d be considered as in the twilight of my career, had I not been escorted to greener pastures already.

I’ll say it again for those in the back: Albert Pujols is a no-doubt first-ballot Hall of Fame guy. Anyone who thinks otherwise is delusional to the point of fan card revocation. There are many in MLB circles who were upset about the way that Perry Minasian and the Halos brass handled the DFA’ing of the legend, particularly when taking into account that he had actually been producing for the club (5 HR, 12 RBI in 92 PA). But the writing had been on the wall for some time when taking into account his production for the club over the past handful of seasons. Sub-.250 BA in each season since 2016, with a maximum of 23 HR and a .430 SLG. His career AVG may be .298, but he did not hit that mark in a single one of the 9-and-a-half seasons he spent with the Angels. It’s also worth considering, with how long he spent at the club, just what is Pujols’ legacy with the Angels? Does he have a signature moment with the club? There was just one playoff appearance (a 3-game sweep at the hands of the Royals in 2014), and a few walk-off homers. I suppose it’d be the fact that he joined both the 3,000 hit and 600 home run clubs in the uniform. But even then, that record is more a product of his time with the Cards than anything.

So, the question that arises in this situation is if Albert Pujols can’t produce above a replacement level into his twilight years, what does that mean for the rest of us? What does that say about what ‘prime’ in baseball might truly be, and who can we look at as paragons (or pariahs) of late-30’s baseball over the last few decades? I’ve taken one example of both the good and the bad from two Hall-of-Famers (well, Ortiz will be one day), and considered what their final seasons say about them – and, in a sense, about us.

THE GOOD: David Ortiz, 2016 (40 years old)

You knew this was coming. Perhaps no season in baseball history has been a better conclusion to a career than that which Big Papi authored in 2016, at the ripe old age of 40. Though a perennial All-Star and 30 home run threat in the years leading up to his swan song, many considered Ortiz to be on the 18th fairway when he entered 2016.

Of course, you probably know how Ortiz did in 2016. He, quite simply, gave us the single best farewell season that a hitter had ever given. He led the league in Doubles (48), RBI (127), Slugging percentage (.620), and OPS (1.021). Digging deeper, he showed improvements in virtually all of the metrics that matter: his 13.7% strikeout rate was the second-lowest of his career, and his Extra Base Hit % (13.9) was the second-highest he’d ever produced. All of this contributed to a 5.2 WAR, his highest number since 2007. His Home Runs (38) and Slugging % were the highest numbers produced by a hitter in his final season. It’s important to note – as many sources at the time did – that WAR number was actually higher than that of Ted Williams, whose farewell season is often lauded as the gold standard.

| David Ortiz (40 years old) | .315/.401/.620 | 38 HR, 127 RBI, 5.0 oWAR |

| Ted Williams (41) | .316/.451/.645 | 29 HR, 72 RBI, 4.8 oWAR |

| Barry Bonds (42) | .276/.480/.565 | 28 HR, 66 RBI, 4.3 oWAR |

| Mickey Mantle (36) | .237/.385/.398 | 18 HR, 54 RBI, 4.1 oWAR |

| Kirby Puckett (35) | .314/.379/.515 | 23 HR, 99 RBI, 3.9 oWAR |

And Ortiz did this on a game-by-game, month-by-month basis. The lowest OPS he posted for a month was the .903 mark he posted in July. That is to say that he tore the cover off of the ball (and walked), without fail, as much as he had when he was in his early 30’s. He even finished 2nd in wRC+ to Mike Trout.

Now, much of this has to do with the fact that Ortiz is a full-time Designated Hitter. It stands to reason that, without the rigor and injury potential inherent to playing an outfield position, his body was significantly better rested than that of a 40-year old second baseman. The last time Ortiz suffered any kind of significant injury was back in 2012 when he played just 90 games. Ortiz was never a denizen of some of the game’s more risky plays – layout catches, stolen bases, having a UCL – and so his body was still relatively intact at 40.

So what’s to be learned from the success of Big Papi at 40? There is something to be said about workload, of course. Being a Designated Hitter negates some of the more significant body stressors that a ballplayer is likely to accumulate. Papi also played on one of the biggest stages in all of baseball, which meant that his every move, success or otherwise, was magnified in the national media eye. His power profile wouldn’t seem to translate. Power is one of the first things to go, even from elite players. But he adjusted his approach in a significant manner. His walk rate, fly-ball rate, hard-hit %, contact %, and swinging-strike rate were all among the best numbers of his career. His 92.9 mph average exit velocity would put him near the top of the leaderboard in virtually every Statcast-era season. Papi also had something to play for all year, as the Red Sox were in a battle all year with the Orioles and Blue Jays for the AL East title.

So, what does Papi’s record-setting age-40 season tell us about aging in baseball? Something that we probably could’ve anticipated. A lessened workload means a healthier body and a greater chance at subduing father time. Having something to play for certainly helps, too. The Red Sox pursuit of a division title meant that they had to play Ortiz as often as possible. He sat only 3 times in the final 62 games and played 151 total games on the season, his highest total since 2005.

THE NOT-SO GOOD: Trevor Hoffman, 2010 (42 years old)

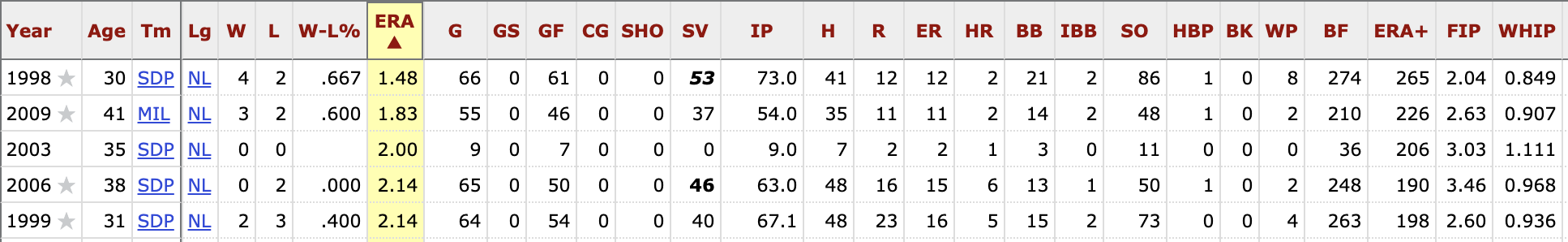

The Hall of Fame closer had a virtually unimpeachable career. In 16 years with the Padres, he posted an ERA of 2.76, 552 Saves in 952 innings, and only posted a K/9 below 8.0 twice in his 16 years. He was the first pitcher to reach the 500 and 600 save plateaus and is second to Mariano Rivera in total career saves. That he did it on consistently mediocre Padres teams meant that he was often not a guy who was in the spotlight, despite holding the Major League Saves record for a (short) time.

In 2008, at the age of 40, Hoffman recorded 30 saves in what would be his final season with the Padres. Many figured he would just ride off into the sunset as a UFA, as the Padres, whose owner John Moores was infamously in a cost-cutting mode that off-season, elected not to renew his contract. But Hoffman clearly believed he had something left in the tank and signed on with the Milwaukee Brewers for a season. He quickly inherited the club’s closer role and channeled that into a stellar Age-41 season. He posted the second-lowest ERA of his career (1.83) while recording 37 saves in 41 attempts and being named an All-Star for the 7th time in his career. He had proven, at least for a season, that he still had it.

Hoffman’s 2009 renaissance with the Brewers was among the best seasons of his career

Hoffman returned to Milwaukee for his Age-42 season in 2010. Unfortunately, the end of his efficacy of a closer came fast and furious. With reduced control of his changeup, an increased home run rate, and the lowest strikeout rate of his career, Hoffman saw his role de-leveraged. He was moved to middle relief and spent the remainder of his final season mentoring young Brewers relievers and pitching in unfamiliar 6th and 7th innings. He did manage to get his 600th save towards the tail end of the year, but with a reduced role and signpost numbers that were easily the worst of his career, it’s fair to say that Hoffman went out with more of a whimper than he deserved. That is if you exclude the epic celebration his Brewers teammates gave him after he recorded that 600th save.

None of this is to say that Hoffman’s Hall of Fame career was at all sullied by a disappointing season; only, that it is very, very difficult for players in any sport to go out ‘on top’. Not everyone can be Jeter, and not everyone can be Ortiz. Even in a sport like baseball, in which players are far more effective late into their 30s and early 40s than in any other major team sport (hello, Jamie Moyer?), physical deterioration is often rapid, and unforgiving. Father Time, as they say, is undefeated.

If anything, it’ll be fun to see how Albert Pujols plays out his final season with the Dodgers. His addition gives that roster 4 MVPs and a healthy heart of the order that should terrify all comers. It’s unlikely that, when the club is fully healthy, Pujols will see regular playing time. His early returns in 2021 have been respectable: entering Monday, he had an xwOBA of .348, an expected slugging of .513, and 7 Barrels in 73 batted ball events, which suggests there’s still some juice in his bat. He also has a 3.3% walk rate, a .176 BABIP, and the slowest sprint speed in the league, though.

So what does all of this say about elite players, peaks, aging, and how one can ‘go out on top’? Well, really, that much of it comes down to the environment. If you’re a player, like a Jeter or an Ortiz, who has built himself up a career as the iconic face of a franchise, sometimes it’s better to reach a consensus with the club on when the tunnel ends and the light comes. There are countless instances of players who stuck it out for a year or two past their peak and ended up wearing jerseys that ostensibly become trivia questions. Mike Piazza as an Athletic? Willie Mays as a Met? Michael Jordan as a Washington Wizard?

Albert Pujols already making in impact for the defending champs 🔥

RBI single in just his second AB

(via @Dodgers)pic.twitter.com/9z3w8whbTP

— SportsCenter (@SportsCenter) May 18, 2021

There was talk that Pujols tried to make it work on a return to the franchise with which he is the most associated. But the Cardinals, for reasons more competitive than sentimental, elected to pass. So we will now be able to add ‘Albert Pujols as a Dodger’ to the pile of ‘Did you know he played there?’ pub trivia. Let’s just hope that Pujols is given ample chance to rage against the dying of that light, though. Goodness knows he deserves it.

PREACH, my brothah!!!:

“I’ll say it again for those in the back: Albert Pujols is a no-doubt first-ballot Hall of Fame guy. Anyone who thinks otherwise is delusional to the point of fan card revocation.”

Anyone that thinks otherwise is the same type that thinks that the Yankees just DESERVE a WS title (and I’m a Yankees fan, but I was around during the 80’s, lol, I know what a Yankees title drought is like. These kids that grew up in and around the shadow of the 90’s dynasty are spoiled AF!)

Pujols is a no-doubt first-ballot guy, IMO.

Still wouldn’t have signed him, even if I were the Dodgers. That’s a 40-man black-hole.

Also *cough, cough Ortiz 2003… cough, cough Mitchell Report, cough, cough…*