Never at any point over the first four months of this season did I think I’d be writing about Néstor Cortes Jr. for the second consecutive week, but here I am!

Now, there is a good reason to write about him. He’s having a great season, after being entirely mediocre (at best) throughout his career. He’s also one of the most unorthodox, fun-to-watch pitchers in the game, as I discussed last week when I explored what’s driving his newfound success thus far. I came to the conclusion that while the sustainability of his performance is questionable (as these types of breakouts often are), he was finding legitimate success through a combination of great command and a supreme penchant for unpredictability, mixing his pitches well and breaking up the rhythm of his standard windup with a whole toolbox full of timing and release point tricks. Like so:

Nestor Cortes, Messing with Timing. ? pic.twitter.com/7a0vRyFoB1

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 11, 2021

That’s cool, but in spite of Néstor’s good results and everything I found last week, it still didn’t really answer the nagging question of whether “messing with timing” actually works. There’s a ton that goes into pitching well, and it could very well just be one questionably effective item out of the many things he throws at the wall to see what sticks.

Anecdotally and experientially, it’s fair to say that in small doses, it probably does something. Baseball is such a game of repetition and routine that it’s hard to believe an infrequent but stark change in rhythm won’t throw the batter off in some sense of the term. And it’s nothing new, either. We’ve been watching Johnny Cueto emulate Luis Tiant since before Pitcher GIFs (the site and concept) was a twinkle in Nick Pollack’s eye.

Relatedly, I came across this “video” while looking for sources to verify that, statement and couldn’t not include it in some capacity.

Anyway! Back to the question at hand: does it actually work? It’s pretty impossible to say, as there’s nothing that tracks it automatically, and as far as I can tell, there’s never been any deep study on it. Current Yankees pitching coach Matt Blake talked about it mechanically in great depth all the way back in 2014 in a guest post for Eric Cressey’s blog all the way back in 2014. The Baseball Cloud blog ran a single-game study on Johnny Cueto’s timing variations, though it didn’t really focus on results. Marcus Stroman has talked about it in quite interesting fashion, but again, there are no large-sample stats that tell us much of anything about its effectiveness.

All this means if we want to find pitch pitch- and PA-level results, there’s not much we can do but watch all the pitches and track them manually. So that’s what I did.

What?

Yeah. The thing is, Johnny Cueto and Marcus Stroman have combined to make 49 starts and throw nearly 275 innings this year. That’s over 4,000 pitches thrown. As the saying goes…

Néstor Cortes, on the other hand? He’s thrown exactly 1,000 pitches on the season. Thanks to the magic of MLB Film Room’s autoplay, that’s a pretty manageable number for a neurodivergent nerd like myself. So, the big question: did I watch all 1,000 of Néstor Cortes’s pitches this season and take semi-detailed notes about the outcome of each one? You bet I did!

Before I go into the results, here’s a link to the dataset, if anyone has any doubts or wants to check it out.

The tracking I did was pretty simple. In addition to noting whether he did some weird stuff with his windup or release point, I marked down whether Cortes was pitching from the windup or stretch, whether the hitter was righty or lefty, what kind of pitch he threw, and what the result was, with results broken up into seven categories: ball, called strike, swinging strike, foul ball, ball in play hit, ball in play out, and ball in play error.

The first thing I needed to do was give at least a semi-clear definition of what constitutes a “yes” in the “messing with timing” column. I didn’t want to just look at the most extreme timing variations, the ones that make for hilarious GIFs. I wanted to include the less-loud but no less distinct changes to timing, leg swing, and arm slot that could reasonably have the same effect.

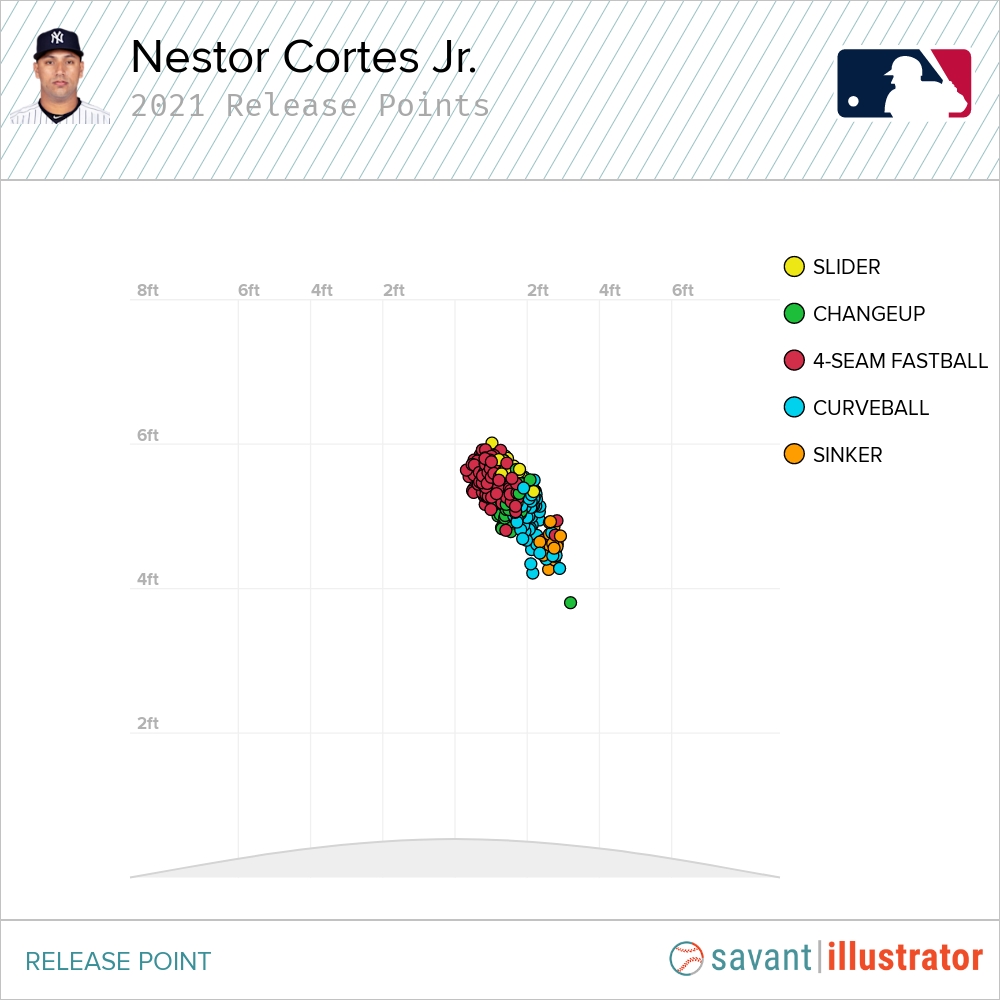

That being the case, I ran into the spectrum issue. Bringing back Cortes’s release point chart for last week, it’s obvious that there’s not quite a clear and definite line between his “normal” delivery and its many variations.

That being the case, I took the Supreme-Court-On-Pornography approach to some of the tracking. I know it when I see it. If you have a problem with that, well, you can go watch all one thousand of those pitches yourself. And to be clear and fair, there weren’t too many close calls. It’s just recognizing that the changes he makes to his release point isn’t always necessarily a trick; it’s partially how he manipulates the movement on his pitches. So while these two pitches come from roughly similar release points, I thought it was fair to say that this didn’t particularly fit the definition of messing with timing…

While this one probably does.

It’s all about context. The latter pitch is clearly a drop-down change-in-delivery to mess with the hitter, the former is just his standard motion while getting around his curveball a little more than he typically does. That’s not the kind of chicanery we’re concerned about here.

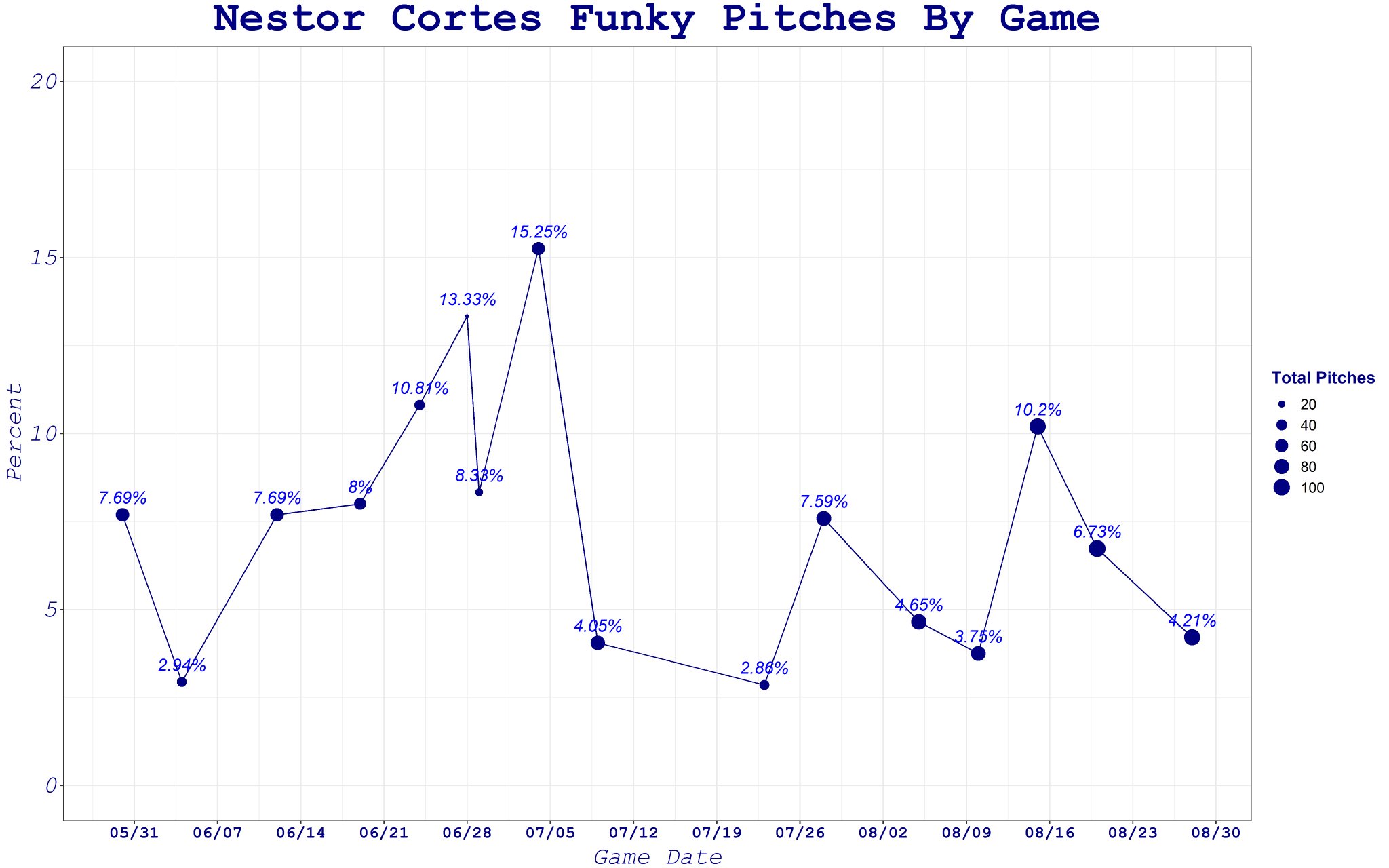

Now that you trust me and my judgment, here are some of the numbers! For starters, of the 1000 tracked pitches Cortes has thrown this year, 70 of them fit my definition of messing with timing, whereby Cortes clearly and purposefully altered his windup and/or release from its typical places. That’s an even 7%, which seems small but is actually a lot of variation when you’re talking about pitchers who are trained to repeat the exact same motion hundreds of times on any given day.

On a game-by-game basis, Cortes has been pretty consistent with that 7% mark, dropping down with the weirdness usually somewhere between four and seven times an outing. Some days, he’s really feeling it, changing things up a full 15% of the time against the Mets on July 4th, and a season-high ten times out of 98 pitches against the White Sox on August 15th..

On first glance, the results don’t show much success. Throwing a ball 50% of the time generally isn’t a good thing, particularly if the subset of pitches aren’t secondary pitches chasing whiffs out of the zone. It’s not super surprising, either. It’s hard to have good control of a pitch when you throw it differently than the other 80 times you’re throwing it that day.

On the swing level, there doesn’t seem to be much there either. An 8.6% swinging strike rate isn’t horrible—league average is around 11%—but it’s nothing to write home about, for sure. That it got an equivalent number of called strikes is more surprising. One would think that the aim would be at least in part to freeze hitters and get a free called strike. But that’s not really happening, making for a 17% CSW that wouldn’t fly if these were any other kind of pitch. The deception isn’t making for many more foul balls, either, as that 18% number is just a hair above league average.

So do we write off “messing with timing” as a wash? Not exactly. There’s more there than what happens on the actual pitches themselves.

No pitch happens in a vacuum. There’s always context: the plate appearance the hitter is in the midst of, the plate appearances they’ve already had against that pitcher that game or that season, the plate appearances and pitches thrown to other batters over the course of the game. It’s a reasonable conjecture that if Cortes does something like this—so ridiculous that the pitch wasn’t even delivered—it’s going to stick in the hitter’s head in some capacity for the rest of their time at the plate.

Nestor Cortes was not in ANY hurry to pitch to Shohei Ohtani ?

(via @PitchingNinja) pic.twitter.com/0DKVmTULnb

— FOX Sports: MLB (@MLBONFOX) June 30, 2021

Ohtani flew out on the very next pitch. When I looked a little deeper into the numbers, I was shocked by how common of an occurrence that seemed to be. Those 70 funky pitches thrown by Cortes came over the course of 52 different plate appearances, and for the most part, those plate appearances did not end well for the hitter.

Woah. Small sample size warnings abound, but that’s pretty remarkable. Néstor Cortes and his 90 mph fastball have a 36.5% strikeout rate in plate appearances in which he messes with timing and release! For context, the league average is about 23%. This is not supposed to happen with stuff like his. And with a 9% walk rate that’s just a touch above his season-long rate of 7.6%, it doesn’t seem to be adversely affecting his control of his other pitches.

The .212 batting average against that we get out of those 11 hits isn’t super misleading either, as only three of those hits went for extra bases. Having watched all of those pitches and all of those strikeouts, my untrained inner-scout can’t help but think that changing up his delivery is absolutely doing something positive for Cortes. Sometimes it’s super visible. Take this Josh Donaldson strikeout from Cortes’s standard delivery:

By just about any measure, Donaldson is a Very Good Hitter who’s also known for having a very discerning eye for the strike zone. How does one catch a former MVP napping with an entirely pedestrian low-90s fastball that gets all of the strike zone? One way might be to spend half the at-bat to that point giving them looks like these:

That still could just be a case of Donaldson thinking he has ball four and just being wrong. But there are enough at-bats like those throughout Cortes’ season that it becomes really hard to chalk up all those strikeouts to random variation. Another instructive example might be Cortes’ matchup with backup catcher Seby Zavala during his August 15th start against the White Sox. With a runner on first and two outs, Cortes starts the at-bat with a pretty pedestrian get-me-over curveball that Zavala can’t quite time up, but didn’t have any issues tracking:

That’s what we’d consider his “regular” motion out of the stretch. Roughly 95% of the pitches he throws with runners on base look like that. Then, with an 0-1 count, he comes back with something a little bit different:

It’s not much, but it’s enough of a departure from his standard fare that Zavala swung miles behind a fastball right down the middle that clocked in at just 89 MPH. One could make the valid argument that Zavala is a Quad-A catcher, but that’s a bit beside the point. Cortes has a three-run lead with a runner on first, and hitters following Zavala are Tim Anderson, Luis Robert, and José Abreu. With velocity and stuff that’s liable to get sent over the fence if it catches too much plate, Cortes needs this out. So what does he do on an 0-2 count? He goes the opposite direction and slows the leg lift down to an even longer stretch than the first pitch.

That misses for a ball. No big deal. The work has already been done: Zavala is thoroughly flummoxed. It took just one more pitch for Cortes to end the at-bat.

Again, right down the middle! But also again, Zavala is a borderline major leaguer, and only that because of his catching ability. Possibly not the greatest example in the world. Fear not, reader. There’s plenty more to choose from. Luis Robert is no Seby Zavala, but Cortes had no issues handling him twice like he did Donaldson, first on a quick-pitch and then on a stolen sidearm strike that Robert was probably never going to swing at under any circumstance.

Yandy Díaz might not be a star in the vein of Donaldson or Robert, but he’s also one of the better hitters in the game at not striking out, doing so nearly 10% less than league average since the start of last season. Critically, he’s also one of baseball’s best at not swinging at pitches out of the zone. His 18.3% chase rate is in the 97th percentile this season. Yet the soft-tossing Cortes got him to do both of those things at once, striking out on a pitch that wasn’t in the zone and never particularly threatened to come near the zone.

That one is less drastic than many of the other examples, but that’s partially the point. The dramatic triple-leg-swings are what reach Twitter, but they’re really just the tip of the iceberg as far as these tricks go. They might have nothing to do with each other (for nothing is certain!), but what I see is that all it takes is that extra pause on the leg-lift (while staring at the baserunner) to take a hitter just a little bit out of their element when he doesn’t do the same thing on the next pitch, or the one after that. It’s like a show-me changeup or get-me-over curveball, in some ways. It’s not necessarily the quality of the pitch itself that matters, but rather it’s very fact of its existence that gives a hitter pause and adds another extra thing they need to think about during a pitcher’s delivery.

Is that enough examples for you? Those are just the highlights, obviously. There were plenty of times where the soft contact or hard outs that followed such changes in pace are harder to directly connect to Cortes’s cunning. Still, there were enough to take note of, and in spite of the sample size, the numbers are still surprising. Until MLB decides to make public the movement-tracking data and technology that they’re now in possession of privately, it’s going to be pretty much impossible to quantify messing with timing. Nonetheless, a microscopic look at one particular pitcher can still be enlightening. As is often the case, it seems like conventional baseball wisdom might have something to it. Warren Spahn famously said that hitting is timing, and pitching is upsetting the hitter’s timing. Néstor Cortes Jr. seems to be demonstrating that upsetting the hitter’s timing can go so far as to help make a major leaguer out of a 36th-rounder.

Photos from Icon Sportswire & Pexels | Feature Image by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)

Not to mention that it messes with guys in the on deck circle before they even get in the box and the opponents running game.

Crafty lefty, indeed.

Wow, dude. Great reading with my morning coffee. Thank you for that. First visit here; very impressed.

Is there any possibility of quantifying this? No.