The 2020 season brought with it a lot of questions in terms of how starting pitchers would perform but few SP’s had me more curious than Dylan Bundy. Nick and I had frequently discussed how if he increased his slider usage and exchanged his fastball dependency for a heavier reliance on breaking pitches he could have success. Pitcher List’s own Michael Ajeto echoed these sentiments in a fantastic Going Deep on Bundy back in December.

As a lifelong Orioles fan, I wanted to believe it couldn’t be that simple. After all, if the way to “fix” Dylan Bundy was to simply tweak his pitch usage, there’s just no way the Orioles – led by Mike Elias and Sig Mejdal – wouldn’t simply have told him to do so.

Right?

Wrong.

Let’s take a deeper look into what has changed.

Ahead With the Curve

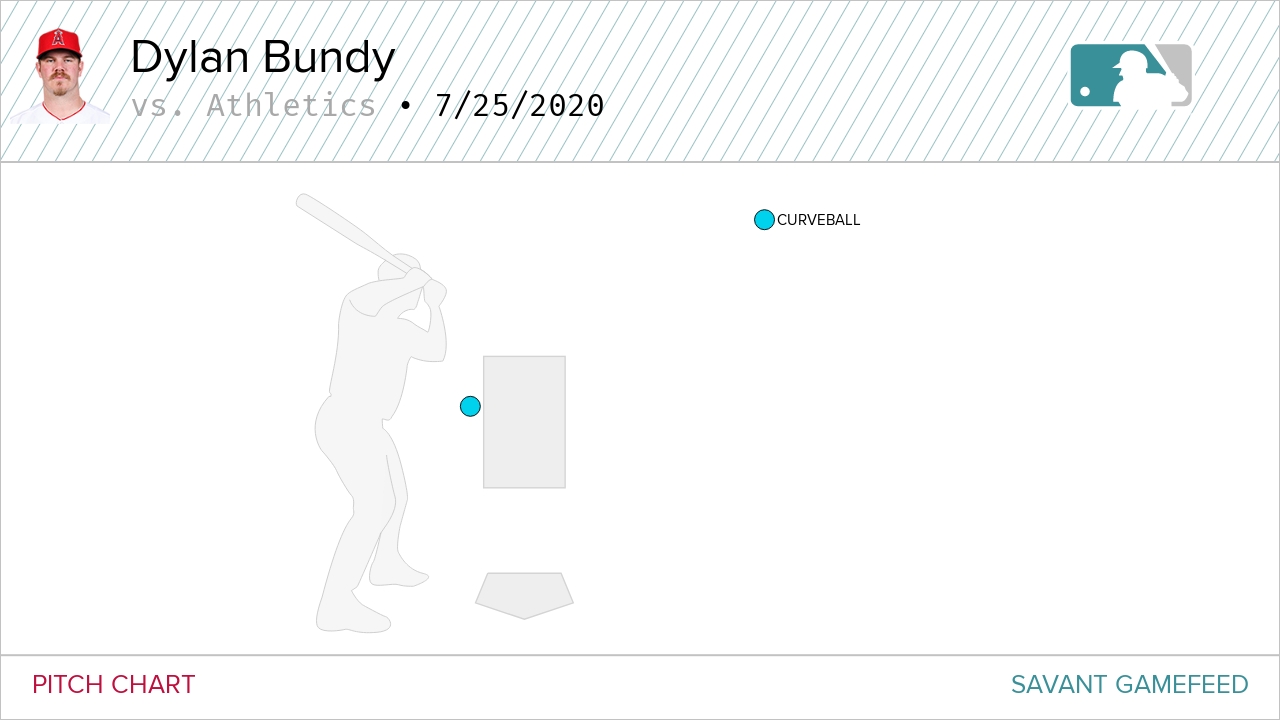

We’ll begin with a pitch by pitch breakdown of Matt Chapman’s at-bat against Dylan Bundy in his 2020 debut.

Pitch #1: Curveball

https://gfycat.com/GlumSolidAtlanticblackgoby

All video courtesy of Baseball Savant

Bundy starts off Chapman with a curve for a called strike* (it’s borderline, but more on that later).

Here’s Bundy’s first pitch curveball usage by year:

| Season | First Pitch CB% |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 31.3 |

| 2016 | 24.8 |

| 2017 | 16.3 |

| 2019 | 15.7 |

| 2018 | 14.7 |

As is the case throughout this piece, we’re dealing with a small sample size but to see a mark above 30% – the highest of his career – leads me to believe we’re seeing a legitimate change in approach.

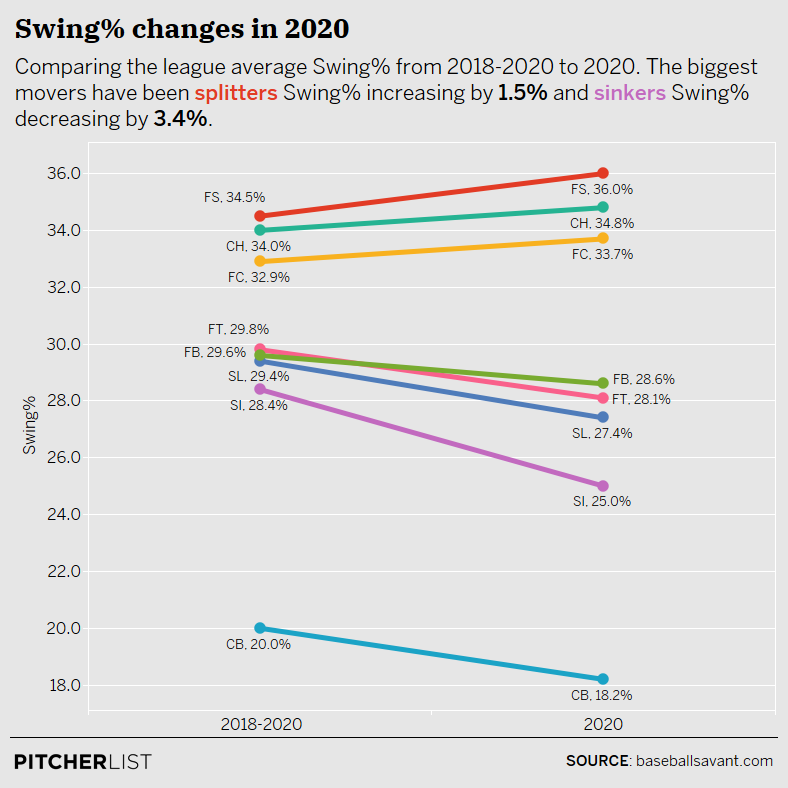

I love first pitch curveballs. Hitters aren’t expecting them, and even when they see them they don’t swing at them.

Data Visualization by Nick Kollauf (@Kollauf on Twitter)

No pitch type is swung at less in 0-0 counts than curveballs (for the sake of transparency, I’ve combined curveballs and knuckle curves in this query). This is true both in 2020’s small sample size and in a larger sample size between 2018 and 2020.

Just because batters aren’t swinging at first pitch curves however, doesn’t mean they’re strikes. After all, they could be laying off because they’re out of the zone.

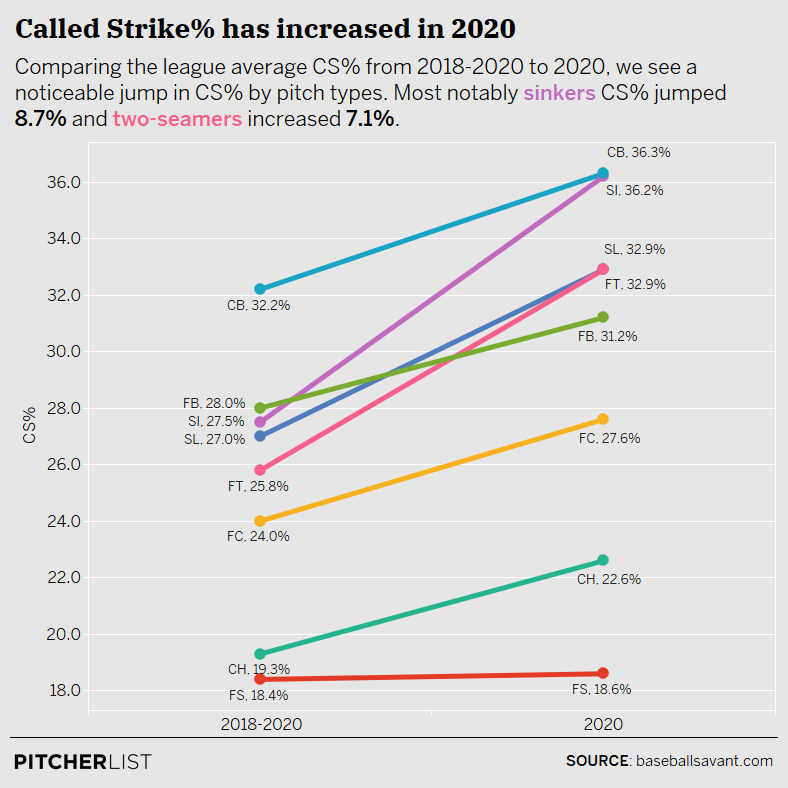

So lets take a look at called strikes in 0-0 counts by pitch type.

Data Visualization by Nick Kollauf (@Kollauf on Twitter)

No pitch type – both in 2020 and in the last three seasons combined – has recorded a higher called strike percentage in 0-0 counts than curveballs.

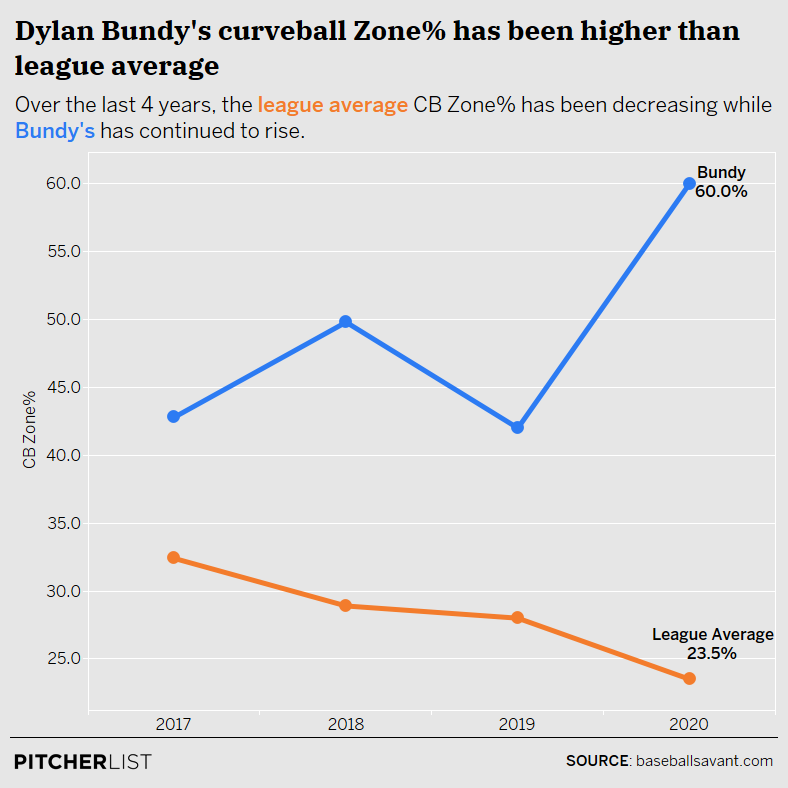

This is all well and good but is predicated upon Bundy’s ability to throw curveballs for strikes.

Data Visualization by Nick Kollauf (@Kollauf on Twitter)

Though we’re looking at just one pitch here, it represents a lot. Bundy is able to get ahead with a breaking pitch that he can consistently put in the zone. The pitch has a 50% CSW, and while it has zero swinging strikes, it has yet to give up a hit and has an xwOBA of .124. That’s a nice weapon to have in your arsenal and to see its usage increased is incredibly encouraging.

Pitch #2: Slider

https://gfycat.com/BlindRightAoudad

This is a gorgeous slider that catches the outside corner for a called strike. At the time of this article, only 15.5% of sliders thrown have been called strikes. Dylan Bundy’s slider called strike rate is 25%, 3rd best in baseball.

If he’s going to have success though, he’ll need to be able to repeat that.

Pitch #3: Slider

https://gfycat.com/WanFeistyIzuthrush

Looks like he can repeat it just fine.

That’s back-to-back sliders which represents the most exciting change for Bundy: an increase in slider usage.

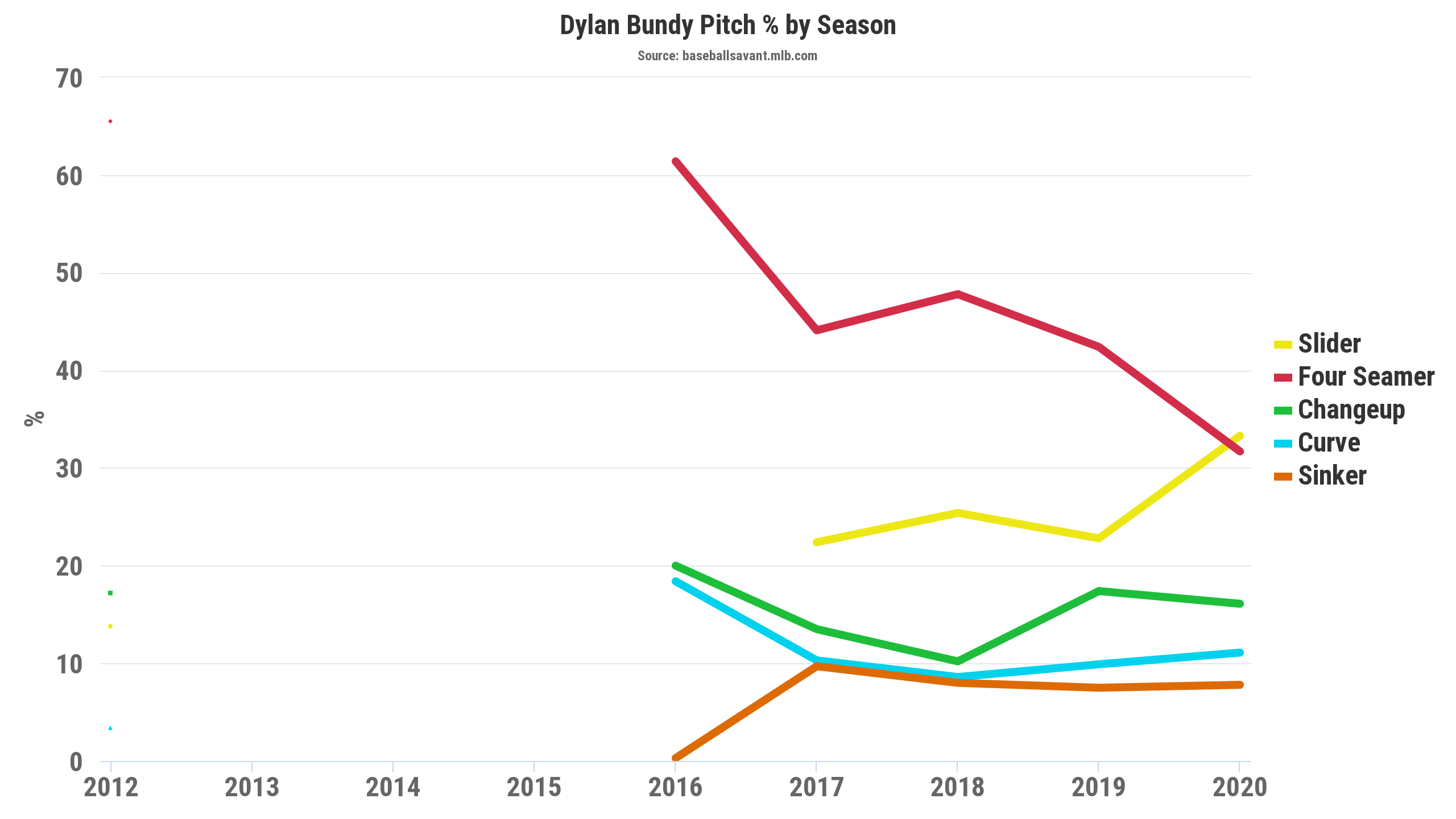

For the first time in his career, Bundy is throwing more sliders than fastballs. While I can’t say for certain that the slider usage will maintain above 30% for the entirety of the 2020 campaign, I believe it’s safe to assume he’s on a path towards having the highest slider usage of his career.

To recap the at-bat: Dylan Bundy threw a curveball, a slider, and a slider. Three breaking pitches. Three called strikes.

It would be a lot easier for me to write off this one particular at-bat as just an at-bat if it weren’t for what Bundy did just three batters later.

https://gfycat.com/ThoughtfulAccomplishedChevrotain

Once again, a first pitch curve for a strike. Once again back-to-back sliders. This time however, Bundy reaffirms what we’ve always known: that slider can get whiffs-a-plenty.

Not So Fast

The most glaring takeaway from both of the above at-bats may be the one thing that we didn’t see: a fastball. It’s no secret that Bundy’s biggest weakness is his heater. It has recorded three straight seasons of negative pVAL’s and hasn’t recorded a sub .350 wOBA since 2016. Between 2017 and 2020, the pitch gave up 48 HR, which is the third most HR any pitch has given up in that time period. It’s not great.

The importance of Bundy becoming less reliant on his four-seamer cannot be understated. As featured in the above pitch utilization graphic from Savant, Bundy’s FB usage has plummeted in 2020 from 42% to 32%. A 10% decrease in fastball usage is not a small sample size fluke, it’s a legitimate change that makes Bundy better. This isn’t just because Bundy is throwing his worst pitch less – though that’s a big part of it – it’s also because he’s replacing his worst pitch with his best pitch in his slider. The drop in four-seam utilization also allows Bundy to be a bit more effective with the pitch. You can see that in Kyle Lewis’s at-bat in Bundy’s next start against the Mariners.

https://gfycat.com/ReadyWaterloggedBarb

Again we see a first pitch curveball for a called strike. Any questions about how important that first pitch curve is should be answered by the second pitch: a 90 mph fastball that Kyle Lewis has no idea is coming. It’s a wonderful example of Bundy’s breaking pitches improving the performance of his sub-par heater. At this point, Bundy is now fully in control of the at-bat and he can do whatever he wants to do: changeup at the legs, curveball in the dirt or, what he ends up choosing, a slider away.

Here’s an overlay of all three pitches just to highlight how tough a go of it Lewis had.

https://gfycat.com/WeakScholarlyGrayfox

While Bundy’s change in pitch mix is largely responsible for his 2.41 FIP and 2.81 SIERA, he’s getting help from behind the plate, too.

Sticking with Stassi

I want to return to that first pitch curveball featured in the Matt Chapman at-bat.

According to Baseball Savant that pitch is a ball but, thanks to Max Stassi, it’s a called strike. The back-up catcher for the Angels was the 7th best pitch framer in 2019 by Runs Extra Strikes, a Savant metric that “converts strikes to runs saved on a .125 run/strike basis, and includes park and pitcher adjustments”. More importantly, Stassi excels at turning pitches on the east/west side of the plate into a strike as can be seen here:

https://gfycat.com/boringwholeapisdorsatalaboriosa

And here:

https://gfycat.com/SmallBoldBlackfootedferret

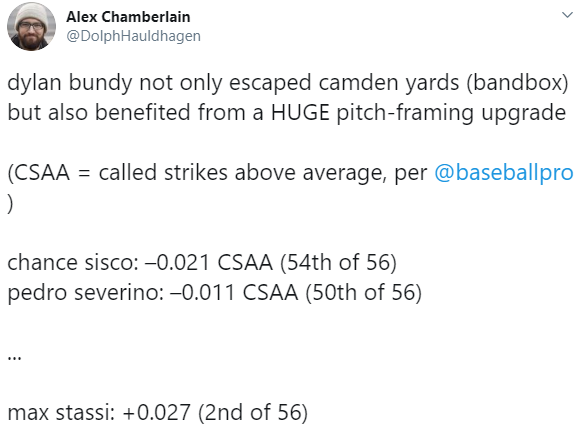

According to Baseball Prospectus’ Called Strikes Above Average, another catcher framing metric, Stassi was actually the 2nd (and 3rd oddly enough) best catcher at getting called stikes. As Alex Chamberlain noted in a recent tweet, this is a significant step up from Bundy’s former battery mates.

To give you a good idea of how impactful an above average pitch framer can be, let’s take a look at Bundy’s called strike% year over year as well as where that ranked league wide.

| Season | Called Strike% | MLB Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 25.6 | 1 |

| 2019 | 16.1 | 167 |

| 2018 | 16.4 | 173 |

| 2017 | 15.9 | 193 |

| 2016 | 15.1 | 231 |

While Bundy’s zone rates don’t lead me to believe he has a problem throwing pitches over the plate, having a top 10 catch framer in Max Stassi only makes him more of a threat.

Looking Ahead

The foundation of this article is two games worth of data which, in the grand scheme of things, is absolutely nothing. There are still fundamental issues with Bundy. His fastball velocity is 90.7 mph – 124th among starters – and the pitch still gives up a good amount of hard contact (his .426/.422 wOBA/xwOBA are way above the .342/.370 league average). Bundy still struggles against lefties – all 4 of his 2020 ER came off the bats of LHH – and his curveball doesn’t have a fantastic amount of active spin to it.

What’s so alluring about Bundy this season however, is the changes that he’s made to his pitch selection seem to address his flaws. By increasing his breaking pitch usage and showing that he can throw those breakers for strikes, batters can no longer just sit fastball. Bundy’s lessening reliance on four-seamers is keeping hitters off-balance and increasing the effectiveness of virtually all of Bundy’s other pitches. The slider hasn’t allowed a single hit yet and has a 25.6% SwSt (the 2nd highest of Bundy’s career). The curveball is a called strike machine and the change-up – perennially one of his better offerings – is posting a career high 20.7% SwSt and making LHH hitters look like this:

https://gfycat.com/felinegiftedfunnelweaverspider

Believe it or not, even with all these changes, I think there’s room for even more growth. Bundy has a second fastball offering in his sinker that, as Michael Ajeto pointed out to me, may benefit him if he increases its usage.

| Metric | FB | SI |

|---|---|---|

| GB | 4.3 | 10.2 |

| HR% | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| BIP | 17.6 | 20.7 |

| wOBA | .383 | .337 |

| Hard Hit | 39.3 | 35.6 |

| wOBAcon | .417 | .393 |

| xwOBAcon | .422 | .391 |

Bolded metrics are from Brooks Baseball and are a % of total pitches as opposed to BIP

When comparing the two fastballs, you can see that Bundy’s sinker elicits more ground balls, gives up fewer HRs and generates weaker contact. While the pitch is by no means elite, it’s a nice offering should Bundy fall behind in the count and not want to rely on his more homer-prone heater. It also seems to tunnel pretty well with that change-up. In the overlay below, the sinker is coming in at 91 mph while the change-up comes in 10 mph slower.

https://gfycat.com/RadiantLightHorsefly

Bundy has never thrown the sinker more than 10% on average in his career but I think if he were to replace a few ticks of four-seam usage with sinker usage, he may find himself with another tool in his shed should he fall behind in counts and not want to rely on his breaking pitches. If, with increased usage, his sinker’s batted ball metrics start to mirror those of his four-seamer, he could always drop its usage once again as he did at the end of 2019.

wOe Is Me

What strikes me about all of this is there isn’t a huge change here for Bundy. There’s no crazy mechanical tweak, the release points aren’t drastically different, the spin rates haven’t spiked, the grips – from what I can see – are the same. All Bundy needed to do was what many speculated he should be doing: dropping his fastball usage and increasing his breaking pitch usage.

It’s both easy and unfair for me to sit behind a keyboard and harpoon the Orioles for not doing this. After all, I don’t know what goes on behind the scenes in the front office. I don’t know if there are underlying injury concerns or if they don’t think this is sustainable, or if Bundy wasn’t interested in making these tweaks in the past but now he is. I also don’t know if Bundy will end the year with a sub 3 ERA and 30%+ slider usage. All I can say for certain is that the Angels were able to take Dylan Bundy’s skillset and make it work better for him.

Great job ALEX. Excellent content as usual.

Thanks a lot!

Life-long Os fan here. Bundy’s starts are historically quite inconsistent. He can go weeks where he pitches like Cy Young. Then the wheels come off and he’ll go 6 or 8 starts where he gives up 3 HRs a game. And not just at Camden Yards. He’s a bulldog, likable and never loses his cool. I hope he maintains his recent great work.

Thanks for checking the piece out, Jerry. I, too, wish Dylan nothing but the best. Excited to see if this can be sustained

Wow. Good information.

Love this article, Alex! I especially love when the answer is as simple as it looks to be with Bundy (Tho I can understand your semi-frustration as an O’s fan). If he still had that 95 MPH heat he used to, I can only imagine what he could’ve been (not that he can’t be effective now of course).