It’s always nice to see old friends succeed. And, for me, Evan Marshall is an old friend. Back in 2017, Marshall spent some time with the Mariners. Six games, to be exact. Over those six games, Marshall walked a lot of hitters and hardly struck out any, which isn’t a great combination, but for whatever reason, I’ve always been fond of him nonetheless. Just the other day, the White Sox signed marquee free agent Liam Hendriks, and Aaron Bummer is great himself, but Marshall deserves your consideration too. He’s made a pretty simple fix. Twice!

Marshall has historically leaned on a sinker that isn’t very good. In 2017 and 2018, Marshall didn’t pitch a whole lot, but up until that point, he mostly threw sinkers and supplemented fairly evenly between his other pitches. Since 2017, Marshall’s sinker has returned a 21.5% CSW, which ranks him in the 13th percentile. Now, a pitcher doesn’t have to convert pitches into strikes, so long as he’s inducing weak contact. The problem is that Marshall didn’t do that either. In the same time frame, he posted a .368 xwOBAcon with his sinker, which is almost exactly league-average.

Given that he hadn’t found much success since his 2014 debut, Marshall moved away from his sinker in 2019 — dropping its usage nearly in half from 37.5% to 20.7%, and lowering his curveball usage by exactly 5.0%. In their place, Marshall bumped up the usage of his change from 23.0% to 39.2%.

That got him part of the way there! His overall .310 xwOBA was the lowest of his career to date, but his K-BB% was underwhelming, and his CSW even dropped a touch, too. Even though he worsened by strikeout percentage and stayed steady by CSW, he took a legitimate step forward by being a pitcher that creates a lot of pitcher-friendly contact. And sustainably, too! It was a minute, but legitimate, step forward.

Adding the changeup wasn’t enough, though. With a newfound ability to suppress hard contact, Marshall needed to be able to throw more strikes. Changeups are generally thrown out of the zone and relatively contactable pitches, which means that even when they post high swinging-strike percentage numbers, they usually don’t earn enough called strikes for a high CSW. Marshall’s slow ball is no different. His sinker obviously wasn’t going to do the job, and his four-seam fastball is only so much better. Marshall made the easy decision to turn his curveball, which proved to be quite judicious.

When I wrote about Tejay Antone the other day, I was creating various search queries and noticed something quite shocking. Sorting by CSW, Marshall’s curveball is the best in the league, with a 50.4% CSW that edges out Joe Musgrove, Dylan Bundy, and Aaron Nola. In other words, when Marshall throws his curveball, it’s a strike, half of the time. It’s staggering.

Like Antone, the vast majority of Marshall’s strikes came from called strikes. Of course, Marshall’s curveball isn’t Bundy’s — it doesn’t have a 13.0% zone-swing percentage — but his 32.7% zone-swing percentage is still one of the lowest in the league. When zooming out and considering curveballs since 2017, Marshall’s curveball’s 30.2% zone-swing percentage is the lowest of all pitchers. Although he has just 260 curveballs thrown since that point, no pitcher’s curveball gets offered at in the zone less than Marshall — at least in this sample. It’s incredible.

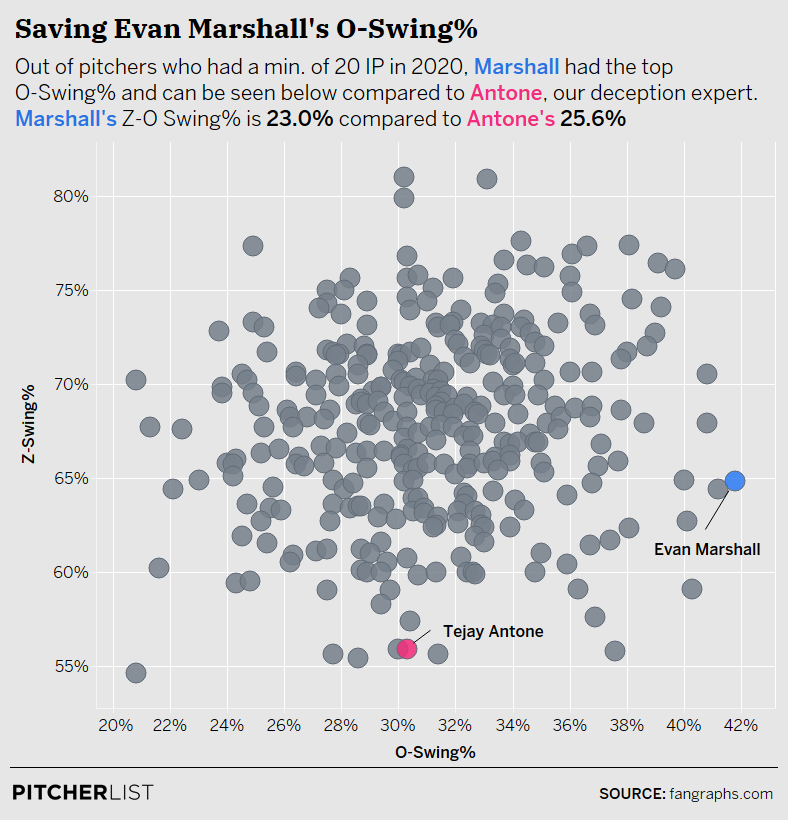

While hitters swing at Marshall’s pitches in the zone more than Antone’s, he ranks much more favorably on pitches outside the zone. To help you visualize this, here’s a scatterplot, via our resident data visualizations wizard Nick Kollauf, comparing the two to the rest of the pack by zone-swing percentage and chase percentage:

Data Visualization by @Kollauf on Twitter

In looking at the scatterplot, Marshall gets hitters to chase more than, well, anyone. That’s impressive enough, but he also gets hitters to take more than a lot of pitchers. In this way, Antone and Marshall go about it in different ways, but they come to a similar end result, with Antone’s 25.6% zone-swing percentage minus chase percentage (Z-O%) being just short of Marshall’s 23.0%. In other words, they’re both two of the more deceptive pitchers in MLB—at least by Z-O%.

What’s even more encouraging, though, is that his pitch mix change and ensuing results aren’t occurring in isolation. It’s hard to say how much is due to the small sample size, and how much is legitimate change. Using it less is one thing. If hitters are increasingly looking changeup or curveball, then it might make it that much more likely that a four-seam fastball or sinker sneaks by for a strike, or causes enough hesitance that it misses a bat. At least theoretically.

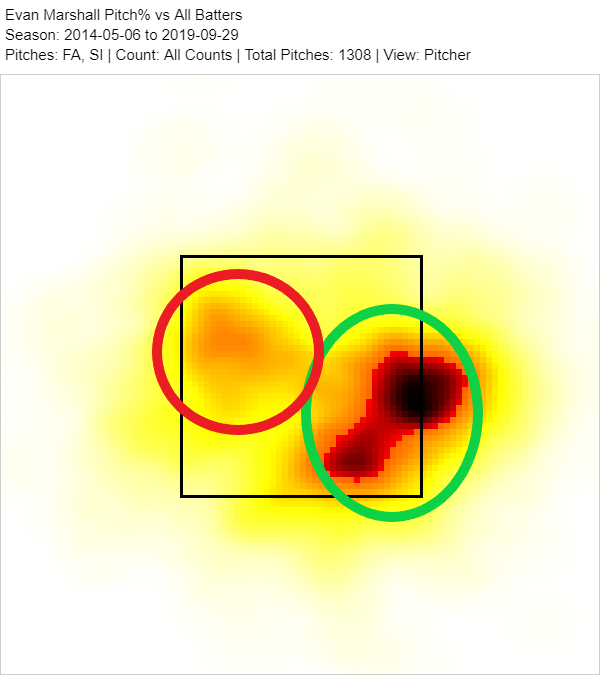

Here’s Marshall’s sinker/four-seamer location from 2014 to 2019, with the green circle signifying his sinker and the red circle his four-seamer:

Four-seamers up and glove-side, and sinkers lower in the zone, arm-side. This isn’t especially unique! In fact, I’d say this is fairly common. What interested me is how Marshall adjusted his fastballs this past year.

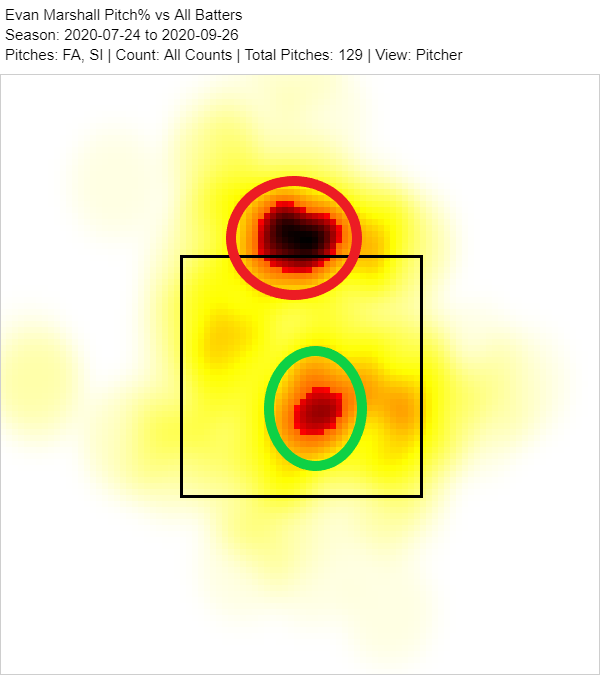

This time, Marshall’s sinker/four-seamer location in 2020, with the same color-coding:

Very different! Very, very different. The fastball has drifted up and to the horizontal-middle of the plate, and the sinker has done the same horizontally. This gets away from the east-west, in and out approach and helps Marshall move towards more of a north-south approach. For now, that’s netted him more swinging-strikes on his fastball, which isn’t at all surprising, but he’s also significantly raised his sinker CSW.

Of course, he’s raised his fastball’s swinging-strike percentage, but its overall CSW has remained steady, and, depending on what tracking system you’re using, the sinker has been extremely effective, although, with 36 pitches, it should be taken with a grain of salt. And so we will!

The change in fastball locations, that’s interesting. But how they’re complementing his other pitches is what I’m really after. His fastballs set him up to do the following with his once-secondary pitches:

He throws both pitches to the bottom of the zone an awful lot. The velocity gap between Marshall’s fastballs and changeup has been closing — and the same goes for the difference in vertical movement — but Marshall’s changeup has continued to thrive nonetheless, which is probably due to Marshall generating seam-shifted wake effects on his changeup. Its 51.6% chase percentage leads all changeups since 2019, and yet when compared to his peers, Marshall hasn’t done a good job of converting his changeup into called strikes or swinging strikes, which sort of leads me to believe that he’s not locating it optimally.

But also, his zone-contact percentage and outside-zone-contact percentage aren’t dissimilar. That’s because, out of all qualified pitchers, no other pitcher’s changeup gets contacted outside of the zone as much as Marshall’s. So, unfortunately for Marshall, it may have as much to do with location as the pitch itself. The curveball, though? It’s been about as good as it gets.

Marshall was like a lot of pitchers, and now he’s unlike a lot of pitchers. He has a whiff pitch in his changeup, and his curveball serves as an elite strike-getter, establishing itself well as a whiff pitch, but also via called strikes. He may not be Liam Hendriks — hell, he might not even be Aaron Bummer — but if he keeps throwing his changeup and curveball as he’s done, he should continue to net strikes at a high clip. Marshall is a perfect example of the modern-day pitcher; his secondaries are no longer secondaries, and his fastballs are used infrequently, but with purpose. There are a lot of pitchers who could use a small but far-reaching tweak, but Evan Marshall is no longer one of them.

Photos by Tony Quinn/Icon Sportswire, Lincoln Ficek | Design by Quincey Dong (@threerundong on Twitter)