Summer, 1963: “They’ll put a man on the moon before [Gaylord] Perry hits a home run!”

July 20, 1969, 1:17 pm: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

July 20, 1969, 1:41 pm: “Perry swings and hits a high fly ball out to centerfield! And it’s way outta here! Home run!”

As far as legends go, this is one of my favorites. Sometime in the summer of 1963, San Francisco beat writer Harry Jupiter and Giants manager Alvin Dark were watching the team take batting practice. After the young pitcher Gaylord Perry took a few hacks that ended up over the wall, Jupiter commented he wouldn’t be surprised if Gaylord hit a few out during the season. Dark didn’t miss a beat. “Mark my words, they’ll put a man on the moon before he hits a home run!”

It lacked the audacity of John F. Kennedy proclaiming We choose to go to the Moon, sure, but it was every bit as prophetic and seemingly every bit as daunting. For over five hundred plate appearances leading up to the first Moon landing, Perry had only a small handful of extra-base hits and zero home runs, all the while NASA and the Soviets sent mission after mission to space, bounding ever closer to their own goal of putting a human on the moon.

Perry certainly wasn’t the worst hitting pitcher in the league. There were plenty of pitchers who were the unfortunate definition of hapless, but Perry wasn’t always one of them. He nearly hit .200 in 1966 – which says more about those other pitchers that fared worse – but was comfortably above the century mark every other year. But through his first 70 plate appearances in 1969, he was in a slump even for those standards. 6 hits. 3 walks. 23 strikeouts. A .100 batting average. Negative OPS+.

The faithful day began minutes before sunrise at 5:52 am when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin entered Eagle, the Lunar Module, that would transport them down to the lunar surface. Gaylord Perry was likely still asleep. After he rose with a good cup of coffee and some pitching day breakfast, Perry headed down to Candlestick Park for the early afternoon ballgame.

At 11:11 am, the two Moon-bound astronauts separated from the Command Module. Michael Collins was left alone to orbit the Moon while Perry, absentmindedly swinging at batting practice, was thinking about how to get Manny Mota out.

At 12:08 pm as the future Hall of Famer may have taken a soft jog in the outfield, that Lunar Module fired up and began lowering down to the surface of the Moon.

At 12:52 pm, Gaylord Perry would’ve been taking his final warmup pitches when Armstrong switched on the landing radar for the final descent.

Just a few minutes after first pitch at 1:04 pm, Perry found himself in a bind on the mound. The Dodger shortstop Maury Williams got an infield hit and was followed by a long Manny Mota triple. Neil and Buzz were a mere 50,000 feet above the lunar surface.

Six minutes later both Perry and Apollo 11 were in trouble. The Dodgers had already scored twice with runners still on first and second. Then Perry walked Bill Sudakis to load the bases with one out. A few hundred thousand miles away, an alarm began to blare in Columbia. The famous (in space circles) 1202 alarm. Neil, Buzz, and the folks back in Houston spent thousands upon thousands of hours studying every contingency and every bolt of the Lunar Module. Though when that alarm went off, Neil said something no one wanted to hear, “It’s a 1202 … What is that?” and Mission Control scrambled.

Gaylord Perry got Ted Sizemore to fly out to right for the second out.

Moments later, Mission Control figured it out and sent back, “Eagle, looking great. You’re Go.” The alarm could be ignored and an abort was avoided, they were now 30,000 feet from landing as Perry got a flyball to end the threat.

Wouldn’t that have been a magical timeline?

The start time of the ballgame jumps around between sources, what I know for sure is that the Moon landing occurred at 1:17 pm California time. Had first pitch been at 1 pm as reported by at least one source, the above would’ve been a play-by-play. But unless the next two innings took 7 minutes total, it would be unlikely.

What’s for sure is that during the top of the 3rd inning at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, the public address announcer’s voice echoed through the stadium, “Ladies and gentleman, please rise in a moment of silence as we honor our astronauts who have just landed on the moon!” The umpires waved their arms to pause play and the fielders looked around in confusion before realizing what was going on, and Willie Mays stood in center holding his hat over his heart with the flag waving behind him. How the crowd stood in silence, I’ll never know.

One presidential promise down of landing on the Moon, one managerial prophecy left to fulfill.

Gaylord Perry was due up 3rd in the bottom of the 3rd. The first two batters were quick outs – I’m sure most of the crowd was still chattering about just landing on the moon when Gaylord Perry strolled to the plate. The Gaylord Perry of a .100 batting average, but the Gaylord Perry with a prophecy to fulfill. He connected on a Claude Osteen hanger and sent it over 400 feet to dead center.

We’ll let Hal Bock from the Associated Press take it away the next day:

The way Gaylord Perry swings a bat, he stands as much chance of hitting a home run as… oh… as a man does of walking on the moon. Well, Perry and astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin made it together Sunday. The San Francisco right-hander tagged his first career homer… while the astronauts took a moon stroll that tightened up the universe.

There we have it.

Except it’s never that easy. Like any good legend, there’s room for interpretation. Some sources say manager Alvin Dark (or somebody) said that quote in 1962, ’63, ’67, or even ’68. The legend slaying website Snopes is skeptical that the quote was ever muttered. These tall-tales sometimes take years to grow legs (like a good Yogi-ism), but the earliest connection I can find happened only eight days after the home run. Journalist Ed Minteer recounted the exact story with the full quote by Dark – and goes on to write a nugget about Perry hitting his next home run when people land on Mars, a goal Vice President Spiro Agnew had set for the distant year 2000.

Gaylord Perry even said the event took place in the early ’60s. Unfortunately, there’s no direct quote from 1963 in any newspaper about the offhanded remark made by Alvin Dark. But there is an odd, almost incredible connection between Gaylord Perry’s bat and the space program. For that reason, I think the legend must be true.

Along with having his first career home run minutes after Apollo 11, the Hall of Famer’s first career double took place June 16th, 1963 the same day the Soviets launched Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman and civilian, into space (right after that hit, Houston catcher Jim Campbell tied a record for three assists in one inning). Two extra-base hits, two historic firsts.

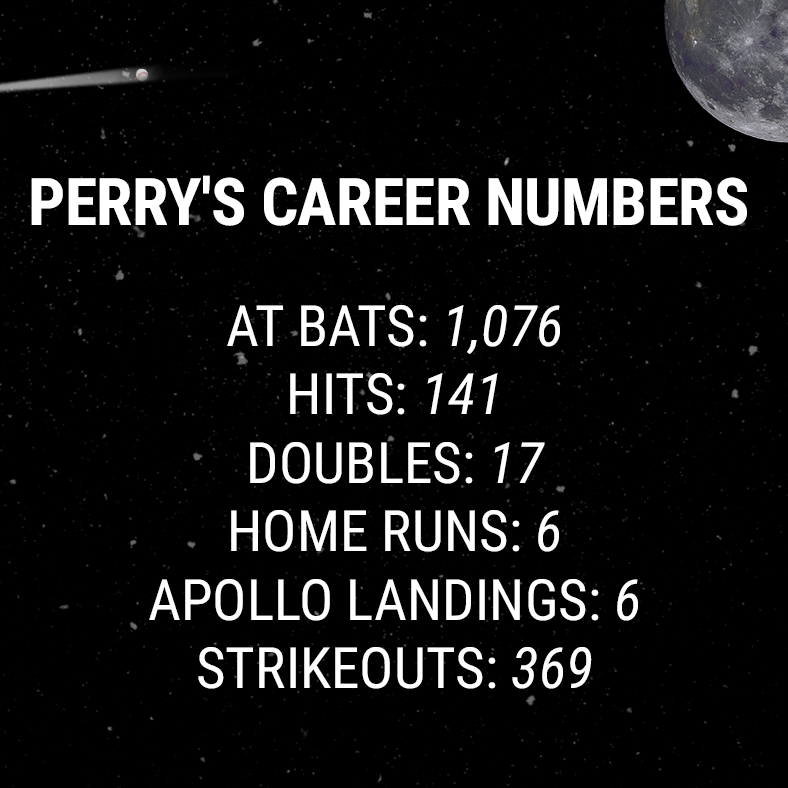

The connection keeps going. Every year the Apollo program intended to land on the Moon, Perry hit a home run.

| Year | Mission | Homeruns |

|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Apollo 11, 12 | #1 |

| 1970 | Apollo 13* | #2 |

| 1971 | Apollo 14, 15 | #3 |

| 1972 | Apollo 16, 17 | #4 |

| 1973 | N/A | N/A |

Perry was traded to Cleveland in 1972 and the Designated Hitter entered the American League the following year, and the Apollo program was canceled (leave it up to the DH to ruin yet another American pastime like landing on the Moon). Perry hit no more.

Until he was traded back to National League where for good measure he hit another homerun in 1979, the same year Skylab – the first US space station and last vestige of the Apollo program – deorbited back to earth. That one’s a little strenuous to connect, I’ll grant you. But Perry’s bat had one last space event to welcome. After Apollo 17 landed back safely on Earth back in 1972, NASA went to work developing a new type of ship: the Space Shuttle. It was under development for nearly a decade when in 1981 the Space Shuttle Columbia launched into outer space.

Then Gaylord Perry hit another homerun.

Featured Article Image adapted by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)