(Photo by David Dennis/Icon Sportswire)

Pitch tunneling is a concept that recognizes how a pitch can travel nearly identical paths with movement or break that occurs late in the batter’s reaction process. To make a decision, a batter relies on release point, trajectory, and spin. In the case of tunneling, when you’re only able to identify the spin (which also happens to be the most difficult of the three), the hitter is going to be handcuffed and forced to rely on instinct.

Here’s a quick glance at the concept featuring Houston Astros starter Justin Verlander throwing a four-seam fastball (red) and a slider (blue) with colored pitch trails. The hitter is unable to react until its too late; one pitch is taken while the other is hacked at.

[gfycat data_id=”FavorableCelebratedFritillarybutterfly”]

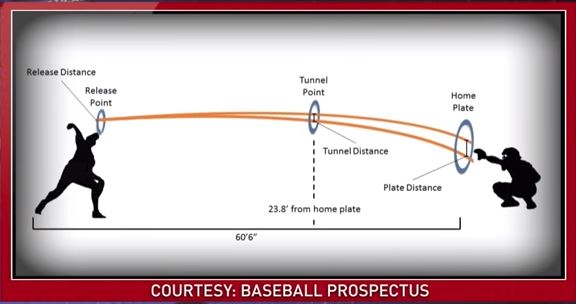

In Chart 1 below, Baseball Prospectus provides a great graphic which depicts how pitch tunneling generally works.

CHART 1

We’re going to take a quick look at few pitchers who recently demonstrated tunneling, starting with Cleveland Indians starter Shane Bieber.

[gfycat data_id=”AmusedAntiqueGalah”]

In the preceding gif, Bieber is throwing an 82 MPH slider in tandem with a 90 MPH fastball. Under close inspection of the gif, you can see he threw both pitches at an indistinguishable release point while keeping the same trajectory until they branch off; usually about halfway between release and catcher’s mitt is where the tunnel breaks. The later the separation, the more difficult it is for the batter.

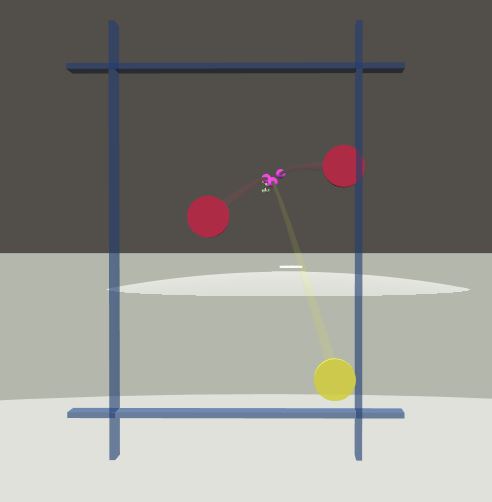

CHART 2

Chart 2 shows the release point for Bieber’s three-pitch at-bat versus Salvator Perez. The sphere on the left and in the middle are four-seam fastballs while the sphere on the far right is a slider. While not perfect, the release points are about as closely situated as you can get.

Have you ever found yourself wondering how in the world a hitter could miss on a pitch that looked so bad (one that was in the dirt, perhaps)? More often than not, this is due to a pitcher who is able to create a tunnel with his arsenal. The batter could be expecting a fastball with light movement, but following the commit point, the ball suddenly breaks and the hitter swipes at the pitch while looking completely lost.

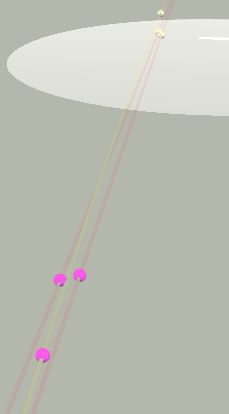

In Chart 3 below, you see the zone perspective of all three pitches. The purple plots indicate where the commit points are for each pitch. We’re talking fractions of an inch at this point from the catchers perspective. It’s at the commitment point where each pitch moves in a new direction; the slider much more drastically.

CHART 3

Chart 4 shows both recognition point (yellow) and commit point (purple). The top-down view allows you to see the separation that contrasts the Chart 2 cluster as well as the decision point where the pitches start to do their own thing. The amount of time between the two points is just 67 milliseconds. The human eye takes between 300 and 400 milliseconds to blink (think about that for a second). Assuming that the hitter wasn’t able to pick up on the spin of the pitch, Bieber was able to fool the hitter who had to adjust his swing at the last second to attempt to make contact with the slider.

CHART 4

Next, we have Zach Wheeler who is throwing both a 97 MPH fastball and an 81 MPH curve. Curveballs, especially of the 12-6 variety, are much more difficult to ‘tunnel’ as they tend to start higher than a pitch like a fastball; the release point and angle can vary as well. However, Wheeler has done a masterful job disguising the two pitches.

[gfycat data_id=”ShowyIllCricket”]

According to the break data logged over at Baseball Savant, both of Wheeler’s throws broke 10.8″ horizontally. What Wheeler does, in this case, is deal the pitch in two ways; throwing the fastball and spinning the curve. He’s able to generate a large break in his curve along the same trajectory as this fastball because of the spin rate of his curve. At 2601 RPMs, Wheeler allows his curveball to hang just long enough in the tunnel with his fastball to cause a split-second guessing game for the hitter. What’s more is Wheeler’s extension difference between the two pitches was just two inches. The longer the pitcher’s extension, especially when you can tunnel a pitch, the better your chances of fooling a hitter (nevermind the increase in perceived velocity).

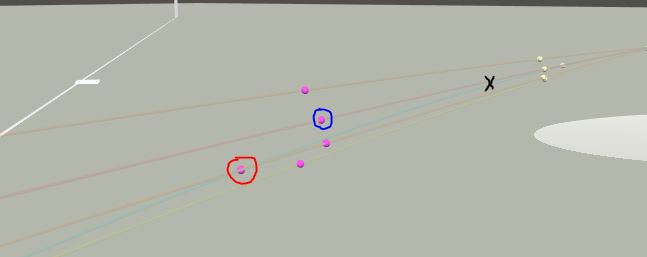

Looking at Chart 5, we see all five pitches from Austin Meadows‘ at-bat which was used in the example gif above. This time, there seems to be a much shorter tunnel (black ‘x’). What causes a problem for the hitter is the difference in commit points. The four-seam commit point (blue circle) appears to be a foot or two sooner than the curve (red circle). That being the case, if the hitter is looking for a fastball when dealt a curve, his commit point will end up being much sooner than it ought to be and he swings early and over the break of the curveball.

CHART 5

Hopefully, now you have a little better understanding of what a broadcaster or analyst means when they reference a ‘pitch tunnel’. I’ve glossed over some of the finer details but this is a general idea. It’s important to note, however, that we need to realize that just because a pitch is released at the same point doesn’t mean it’s going to be tunneled. Several points I’ve made, to include spin rate and extension, can effect the way a pitch behaves and its trajectory to the batter.

Let’s now have a look at a three-pitch overlay from Max Scherzer.

[gfycat data_id=”AgitatedImperturbableArctichare”]

All three pitches are released at the same point in space, break apart a little more quickly than the other examples, but is perhaps still considered ‘tunneling’. Pitchers like Scherzer don’t really need to use a skill like tunneling because his pitches by themselves are just that good. When he does, he’s almost unhittable.

But again, as exemplified below by Houston Astros Gerrit Cole, keeping a pitch inside a tunnel is a huge asset to a pitcher who may not have the greatest stuff but is able to hide certain secondary pitches behind their fastball.

[gfycat data_id=”PerkyAngryIbizanhound”]

I think Lester is one of the best at tunneling. Part of the reason how he is always able to perform better than the FIP and SIERRa

It’s a good question, and I’ve wondered the same thing. My thoughts are, since SIERA includes balls in play, it would make more sense if Lester’s ERA were to outperform FIP & xFIP as they do not include BIP. Lester’s pitch tunneling skills would show up more in SIERA because of the weak contact generated from very good pitch tunneling. Therefore a bigger discrepancy would arise between FIP and ERA.

Do some guys not do this? Are they less successful? It seems like one of the many difficulties of hitting to me. I always thought this was just for cool gifs and not a whole more than a buzzword…