Anibal Sanchez has been in the game for a long time. He’ll be 35-years-old on Feb. 27 (happy early birthday Anibal) and has been in the league since 2001 when the Boston Red Sox signed him as an international free agent.

There’s little doubt that you know who Anibal is if you’ve been following baseball because he was a pretty successful pitcher early on in his career. In his 2006 rookie season with the Florida Marlins, he was excellent, pitching to a 2.83 ERA over 114.1 innings and even throwing a no-hitter.

The rest of Anibal’s career is marked by inconsistency. He followed up that rookie campaign with a 4.80 ERA season and floated around between being an excellent pitcher (he was the AL ERA leader with the Detroit Tigers in 2013 with a 2.57 ERA) and being a really bad one (like his 6.41 ERA in 2017).

After his garbage 2017 season, I think just about everyone was surprised when he, at 34-years-old, turned in one of the best seasons of his career, with a 2.83 ERA, 1.08 WHIP, and 8.89 K/9.

But if you, like me, took a quick glance at his peripherals and saw a 3.62 FIP and a .255 BABIP and said “Bah, just Anibal being lucky, he’ll be back sucking next year,” I wouldn’t blame you.

But I think there’s more to it than that—it looks to me like Anibal made a specific change last year, and that gives me optimism that he might be successful again this year.

Anibal’s Changeup and Cutter

I think the key to Anibal’s success last year is how much he toyed with his repertoire. He totally revamped his changeup and cutter and it worked wonders.

Let’s start with his changeup.

Last year, Anibal’s changeup was the 10th most-chased pitch in all of baseball with a 49.3% chase rate. That chase rate also came along side a 20.9% SwStr rate.

Even if hitters could hit the pitch, they didn’t do anything with it, posting a .185 wOBA and .061 ISO against the pitch. It also ended the season with a 15.1 pVAL, the best pVAL Anibal has every had on a pitch in his career, which was good for the 10th-best changeup in all of baseball by pVAL.

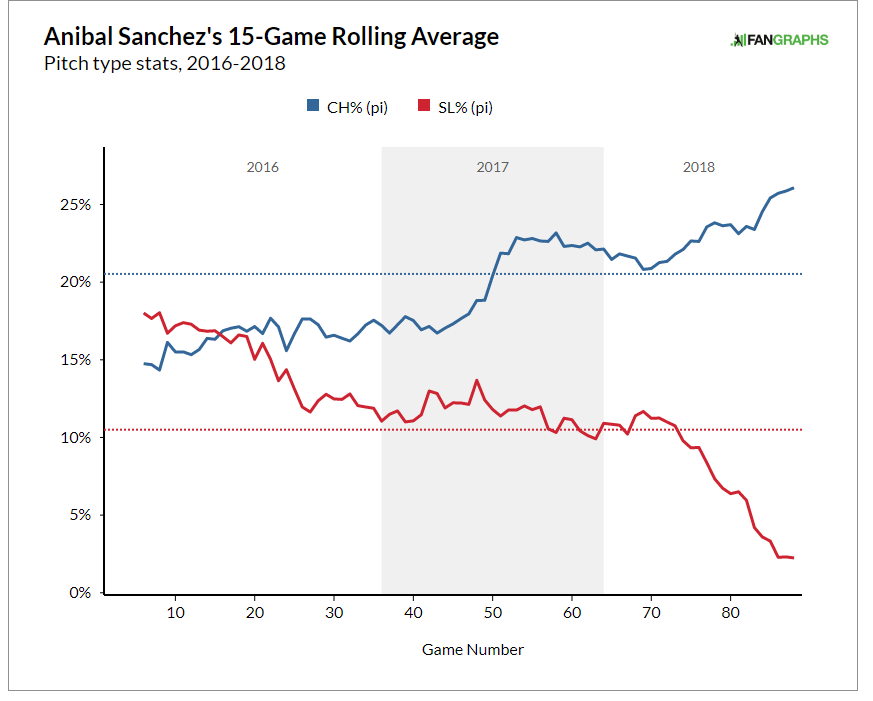

Since the pitch was so effective, Anibal was using it a lot more as a stirkeout breaking pitch. He also started using his slider a lot less.

That’s a good thing, because his slider was not a very good pitch. Last year, it posted a measly 26.2% chase rate and 8.6% SwStr rate, and hitters teed off on it, posting an absurd .417 ISO against the pitch.

That’s generally been the case with the pitch over the years—in 2017, it had a .258 ISO against, in 2016 it was .257, and in 2015 it was .241. So it was a very good idea for Anibal to throw it way less (it was his least-thrown pitch last year).

Now for his cutter.

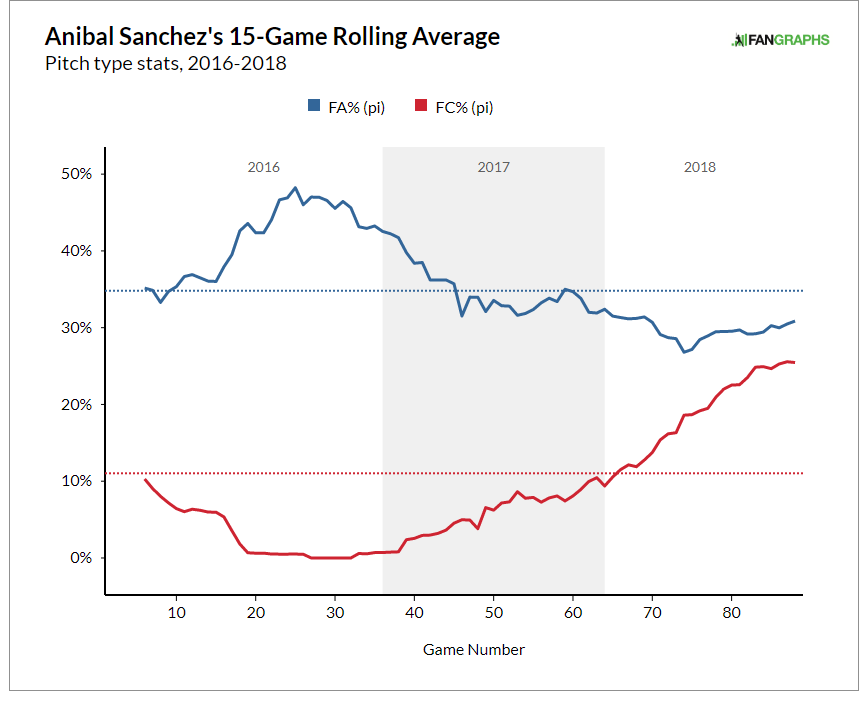

Anibal has only been throwing his cutter since 2015, and since he started throwing it, it’s been his least-used pitch. That is, until last year, when all of a sudden it jumped up to his third-most used pitch as he started using it in place of his fastball.

Similar to him replacing his slider with his changeup, Anibal increasing the usage of his cutter and cutting (you’re welcome) down on the usage of his fastball is a good thing. Last year, opposing hitters had a .382 wOBA and .228 ISO against his fastball. Against his cutter? They had just a .242 wOBA and .120 ISO.

Also, remember how I said Anibal’s changeup posted the best pVAL of his career? Well his cutter posted the second-best pVAL of his career at 12.4, good for the fourth-best cutter in baseball when ranked by pVAL.

And yes, if you noticed, Anibal had two different pitches ranked in the top 10 of their respective pitch type when ranked by pVAL. The only other player in baseball to do that last year? Jacob deGrom.

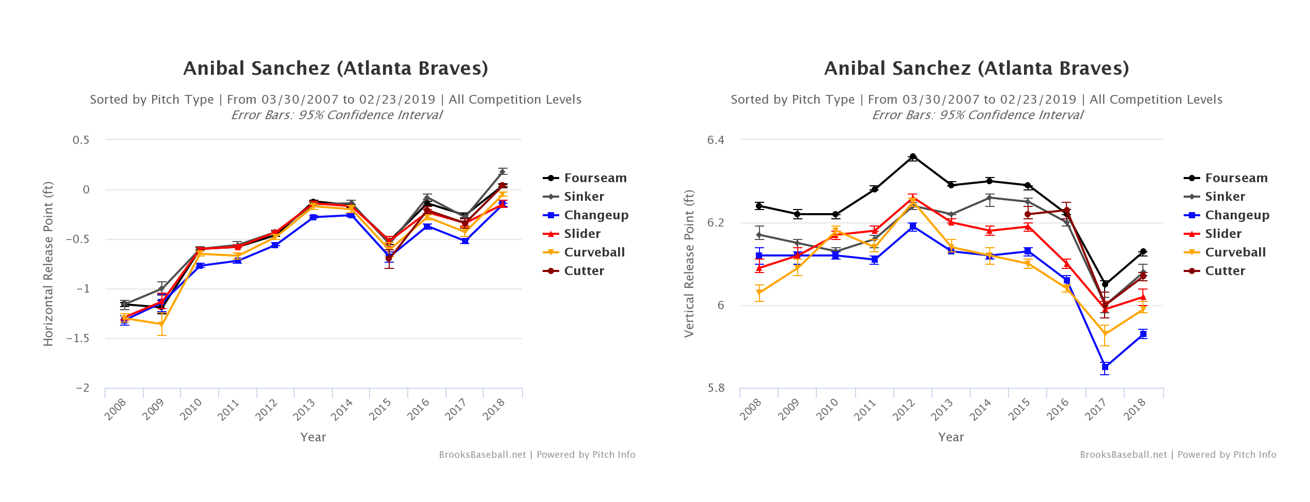

There’s also one other small change Anibal made to his game last year that I want to point out—he changed his release points, both vertical and horizontal.

This isn’t a huge change, but it’s a noticeable one, and could help explain part of his success last year.

The Results

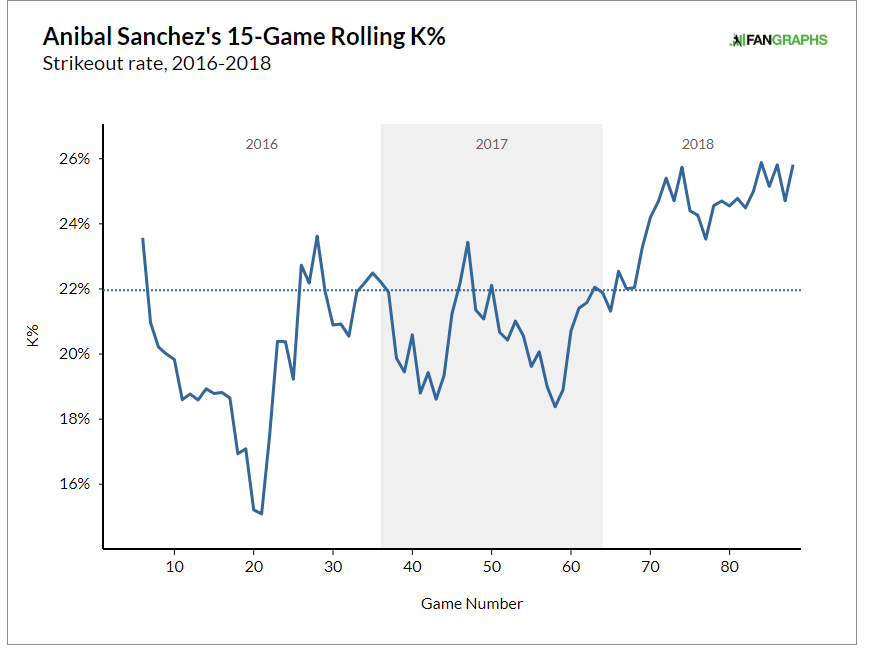

So what affect did these changes that Anibal made have on his game? Well, he started causing a lot of swings and misses and started striking guys out more.

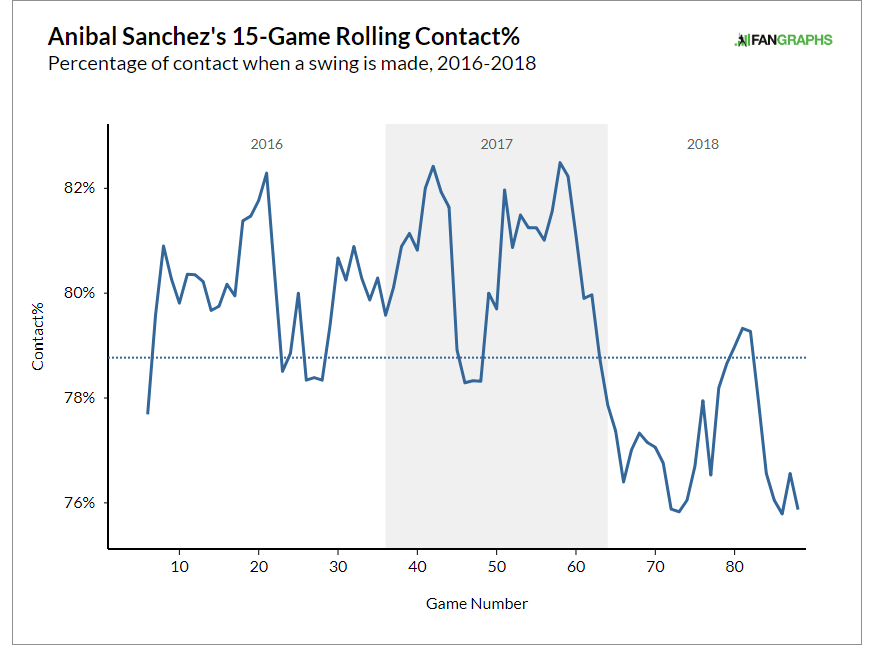

And as a result, hitters started making a lot less contact against him.

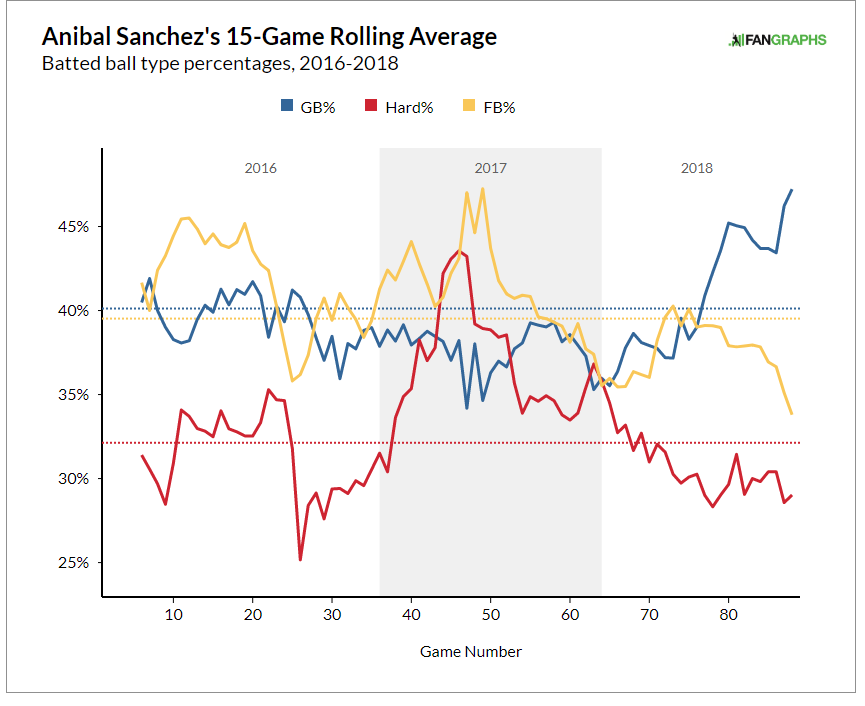

And even if they did make contact, it wasn’t good contact, as his hard-hit rate and fly ball rate started dropping and his ground ball rate went up.

In fact, if you take a closer look into his batted ball data, it looks really good, especially when you compare it to the past few years.

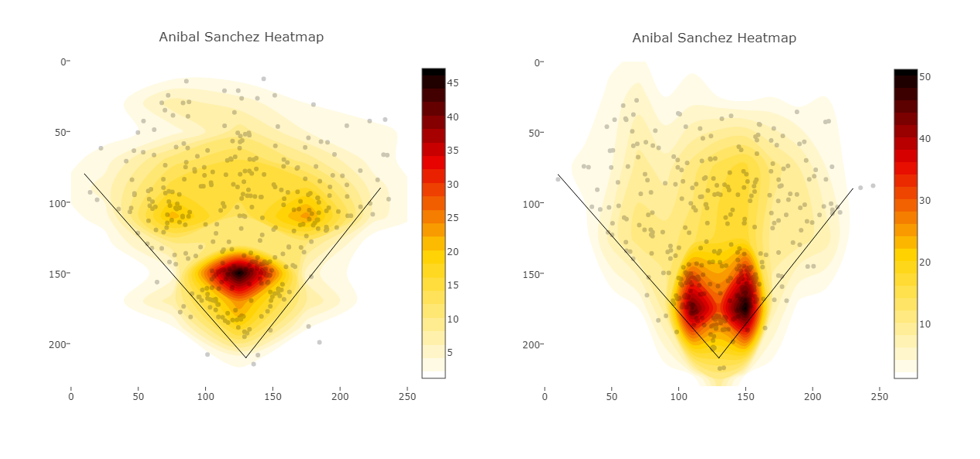

First, let’s take a look at a heatmap of where hit balls went for Anibal (2017 on the left, 2018 on the right).

As a pitcher, you don’t want a whole bunch of pitches going right up the middle, because those are not going to be easy outs (they’re often the line drives or ground balls that go right into the outfield past the second baseman or shortstop).

Instead, Anibal saw contact against him shift to the corners, essentially right where his third baseman and first baseman would be. And given that we know his ground ball rate jumped up, we can surmise that he saw a fair number of weak ball hit to the corners.

Actually, we don’t even need to surmise that, we have that data. Let’s take a look at his batted ball data via Andrew Perpetua’s xStats. There are six types of hits here:

- Dribble balls (DB)—these balls are the weakest-hit balls and typically don’t leave the infield. They have a very low batting average and extra base hit rate.

- Ground balls (GB)—these are the next step up from dribble. They’re ground balls hit a bit more sharply than dribble balls but still rarely result in extra base hits (though they do often result in singles—hitters had a .351 average on ground balls last year).

- Low drives (LD)—these pitches have very high success rates (hitters had a .766 average on low drives last year) but still don’t often result in extra base hits.

- High drives (HD)—these are the best hits a hitter can make. They’re not overly common, but they’re great. Last year, hitters had a .656 average and, more importantly, a 2.059 slugging percentage on high drives.

- Fly balls (FB)—these are pretty much exactly what you think they are—fly balls hit into the outfield that don’t always result in a hit. Last year, hitters had a .253 average on fly balls. They’re not bad hits, but they’re not great either.

- Pop ups (PU)—similar to fly balls, these are exactly what you think they are—pop up hits that hit high in the air and almost always result in an out. So much so that hitters had a .024 average on pop ups last year.

So let’s take a look at Anibal’s xStats quality of contact from 2015 through last year:

| DB% | GB% | LD% | HD% | FB% | PU% | |

| 2015 | 23.5% | 18.4% | 17.8% | 9.3% | 10.8% | 20.1% |

| 2016 | 20.2% | 22.1% | 14.7% | 11.8% | 10.1% | 21.1% |

| 2017 | 19.7% | 19.7% | 16.5% | 12.5% | 11.0% | 20.6% |

| 2018 | 31.2% | 16.4% | 14.5% | 9.4% | 9.7% | 18.8% |

So what does that tell us? It tells us that Anibal started inducing a lot of very weak contact last year, as evidenced by his huge jump in percentage of dribble balls. So like I said earlier, a lot of the balls hit against him were poorly-hit balls rolling to the corners, easily fielded for an out. It’s also worth noting that he saw the worst kinds of hits for him to give up—line drives and high drives—drop fairly noticeably last year.

Conclusion

Now, look, I’m not going to tell you that Anibal is going to repeat his 2018, I don’t think that he is. However, what I will say is that it’s pretty clear to me that Anibal made some significant, noticeable changes to the way he was pitching last year, and that suggests to me that this could be somewhat sustainable.

He’s with the Washington Nationals now, and there’s a pretty safe bet he’ll have a rotation spot. While I do think some regression is in order, I could easily see him being a guy with an ERA in the mid-3s with a decent strikeout rate.

Right now, Anibal’s ADP is 294, so right at the end of drafts, and I think he’s 100% worth a look at the tail end of your draft, because there’s a chance he could be a pretty solid pitcher once again.

Photo by David John Griffin/Icon Sportswire

I don’t think this article really tells the story accurately. His change-up has always been good, but it was less effective the last few years because he had nothing to play it off. The slider hasn’t been a big part of his repertoire since 2014. What happened was that he replaced his normal fastball with a cutter. The cutter worked for him, but what it really did was allow the change-up to play up again.

The question for him will be whether the cutter continues to be such a strong pitch for him. If not, he is likely to completely collapse, because the change-up will no longer be effective, and 2017 Anibal will be back.

I think we’re sort of in agreement here. I mentioned the cutter/fastball replacement, and I agree, his success this year will in part hinge on how effective his cutter is.

As for the slider, you’re right, usage of the slider has been dropping for a bit now, but it dropped significantly this past year. He cut the usage of his slider nearly in half to a career-low usage (11.6% usage in 2017, 5.4% last year), and his changeup went up to a career-high usage (24.9% last year). So while he wasn’t using his slider a *ton* in the past, he was still using it a decent amount, and he clearly made a pretty specific effort to almost never use it last year.