Though it’s become somewhat endangered, a pitcher who throws a two-seam (or sinking) fastball can create some of the coolest movements of any pitch. Whether it dips, runs or cuts, the motion isn’t so much graceful as it is aggressive in its trajectory. This isn’t to say that the curveball or slider is without their own merit, but these eyes get easily dazzled by this fastball variation.

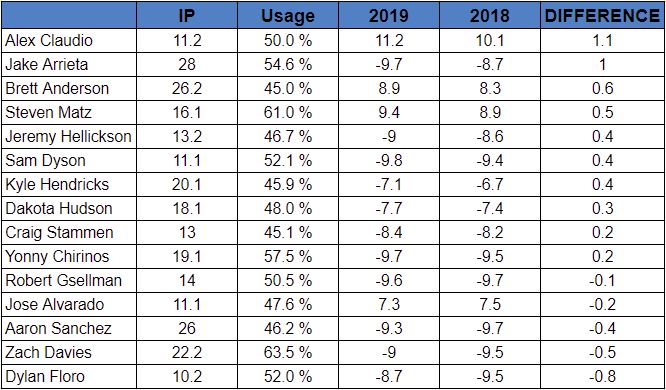

Let’s look at all the pitchers who’ve thrown the two-seam at least 45% of the time (through a minimum of 10 innings pitched as of April 22) and compare their 2018 average horizontal movement with their current metrics, arranged by the variance in movement.

This is obviously the best place to start, but before we get ahead of ourselves, we need to understand that more movement doesn’t mean better movement. Adding an extra inch of horizontal movement, as Alex Claudio and Jake Arrieta have, can have all sorts of implications, and that’s what we’re in search of.

I also need to point out that the pitchers at the bottom of the list shouldn’t be ignored just because they’ve lost movement. Dylan Floro, for example, might have gained extra vertical break on his fastball, which could be making it a more effective pitch at the expense of run. But as I stated before, we’ll be looking more horizontally than vertically, so don’t assume I’m dismissing the rest of this list based upon lack of change or decrease in horizontal movement.

To get a better idea of what kind of impact this might be making on the pitcher’s command, let’s bring our focus on three who have seen the most added run (Claudio, Arrieta, and Brett Anderson) and two who have created a deficit in movement (Zach Davies, Floro) who all have shown more than a half inch extra horizontal break.

The most basic way to look at the implications of this change in movement profile is to look at their release point data.

For the most part, we are looking at a minimal change to horizontal release points, the exception being Davies, who has pulled his release point in by a half inch. I’m only looking at horizontal release because that can give us a better idea about how the pitch is behaving in conjunction with the altered movement.

Instead of lumping our quintuplets into one group, we’ll break each one of them down on the basis of their movement and release point change.

Anderson’s pitch is moving an extra .6 inches while having a .17 inch wider horizontal release in 2019. As I mentioned before, more movement isn’t always good movement and Anderson is exemplifying that. His Pitch Info two-seam rating has gone down over two points this season, from a 1.37 wSI/C to a -1.44.

Likewise, his batting average against has jumped from .253 in 2018 to .308. He’s not throwing the pitch much differently in terms of his grip. A 6-degree axis change isn’t a lot, but if other metrics are changed as well, then that might be enough causation for the movement variation. Anderson’s spin rate has increased by only 20 RPMs and his velocity is up by .3 MPH (the only pitcher in this group to increase his velocity).

So what’s done Anderson’s two-seamer in this year? Location. Have a look at his heat chart from 2018 and his current chart.

His two-seam in 2019 is concentrated more in the middle of the strike zone and a bit outside. That zone produces a league batting average of .337. Whatever has changed for Anderson is causing the pitch to ride into the zone further instead of staying near the edge, where batting average drops over 30 points.

Contrary to Anderson, Arrieta’s sinker is vastly improved according to PI pitch value. A 3.15 improvement has been backed by his batting average against, which has dropped from .270 to .153. Not much has changed in the how and why of Arrieta’s use of the two-seam—he’s still using it a little over 50% of the time, much like he did last season. However, Arrieta is using it on lefties when he gets behind about 20% more often than in 2018 and about 10% more when he’s ahead or with two strikes against right-handed hitters.

So what’s the deal, Jake? His spin axis is only altered by two degrees with little change to both velocity and spin rate. He’s also throwing the pitch out of the same arm slot as last year. What Arrieta appears to be doing is busting the pitch inside with extra arm-side run. In 2018, he was more middle up in the strike zone, where hitters were having a lot of success against the pitch. While Arrieta’s exit velocity against his two-seamer has gone up roughly 2 MPH, he’s focusing the pitch more in the zone where his average EV is actually the lowest.

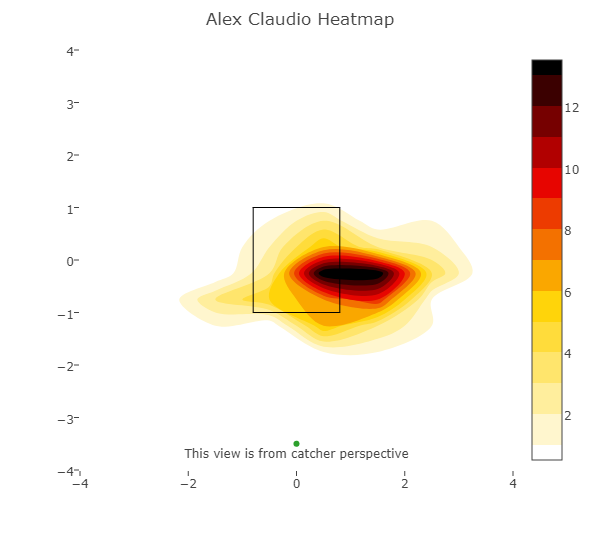

Claudio, a bonafide side-armer, leads the pack in movement, albeit by just a tenth of an inch. He’s using his two-seam a lot more when he falls behind lefties and a little less to put away righties. The pitch is much improved so far in 2019, despite the fact that its lost 1.6 MPH. Velocity loss isn’t always a bad thing if you understand how to compensate in other ways. Claudo has increased his spin rate by 30 RPM on average while still maintaining all other proclivities from 2018.

It’s hard to say if that extra 30 RPM coupled with the loss in velocity is what’s helping create the extra movement. If we use Bauer Units (BU), we find his BU score was 22.96 while his loss in velocity and gain in spin rate has his current BUs at 23.75. Does that mean he’s getting more out of the pitch (in terms of effective spin)? Maybe. Claudio’s 75-degree spin axis would lend itself to more backspin (drop) than sidespin, but because of the arm angle, he throws from it induces more run than drop.

Claudio’s heatmap shows the two-seam has become more of a ‘back-door’ pitch as opposed to his 2018 version.

He’s not getting hitters to chase the pitch out of the zone as much as he did last season (38.6% vs 24.1%) and his whiff rate is down. You would think with the additional horizontal movement, he’d miss bats more, but Claudio is actually causing hitters to drive the pitch into the ground on 82.4% of contact. With not that much extra vertical break (.18 inches more), it’s interesting that the ground-ball rate is so high on the pitch. His 2018 batting average on the two-seam was .337 last year. In 2019? .250. Do keep in mind, though, that we are working with a pretty small sample size thus far with Claudio being a relief pitcher.

Davies is one of our two ‘losers’ whom I’ll briefly profile as a contrast to the pitchers who are adding on to their movement. Right out of the gate, Davies has changed his horizontal arm slot by almost half an inch this season and has seen his spin axis altered by 8 degrees in favor of a more sidespin release.

Here’s a slow motion example of Davies 2018 (right arm) vs 2019 (left) arm slot.

2018- Blue, 2019- Red

The pitch is about as effective as it was last season, but Davies has subtracted about 1.5 MPH and added 110 RPM. He’s still locating the pitch, mainly down and in to righties, and what makes Davies case unique is that his arm adjustment is directly correlated to his movement reduction. That said, any change in the movement for Davies has had a negligible impact of the overall performance of the pitch. Davies’ more vertical arm slot, coupled with the additional spin rate, has allowed his two-seam to drop almost two inches more than his 2018 version. So, he’s basically traded run for drop. The only negative to speak of for Davies is that the pitch is allowing an extra 15 points in terms of batting average (.269).

Floro has lost almost a full inch of horizontal break on his two-seam. Like Davies, his spin axis has changed by 8 degrees in favor of more sidespin and has also gained additional vertical break—just over a full inch with little to no adjustment to his release point. Floro’s spin rate increased by 66 RPM while he only lost maybe .4 MPH on the pitch. His batting average against is down 58 points, while his PI pitch value is up 1.89 points (0.54 in 2018). His 2018 two-seam use contrasted against his 2019 use shows Floro is attacking hitters with the two-seam earlier in the count and leaning on it more when hitters have the advantage.

With the exception of Anderson, all pitchers we looked at saw some level of improvement early on in 2019 regardless of how much more or less they are getting the pitch to run. In some cases, the pitchers adjust their mechanics (release point, spin axis, etc) to create more of a vertical break than a horizontal break. Or, it’s also possible we are dealing with pitchers who are standing at a different spot on the pitching rubber. This is a stab that might be worth looking into down the road. But as we see, a change in movement profile doesn’t always correlate to an improvement or degradation of a pitch.

–All data has been appropriated from Fangraphs, Brooks Baseball, and Baseball Savant.

Photo by Dan Sanger/Icon Sportswire.