Back in mid-April, our own Nick Gerli wrote an incredible article covering a brand new statistic he, himself, invented: Two-Strike Rate (or 2-Stk%). It’s a rather intuitive concept that you want to “get ahead in the count” as a pitcher, so Nick was inspired to dig into this concept further in order to find out WHY “getting ahead” is so important and to see how correlative the skill is to meaningful outcomes for a pitcher like ERA. As it turns out, Nick was on to something big, as 2-Stk% wound up correlating almost exactly as strongly as Swinging-Strike rate to Strikeout rate, ERA and FIP while actually stabilizing quicker. It’s a fantastic finding that gives all of us another significant skillset to track and incorporate into the analytical puzzle that we continue to find more pieces for, and I have been working closely with Nick in an effort to expand the 2-Stk realm and dial in its forecasting capabilities. It’s important to remember that 2-Stk counts include counts in which the pitcher is “ahead” with two strikes, so 2-Stk% is the number of pitches thrown in 0-2, 1-2 and 2-2 counts as a percentage of total pitches thrown. With that covered, let’s dive in.

A Quick Recap…

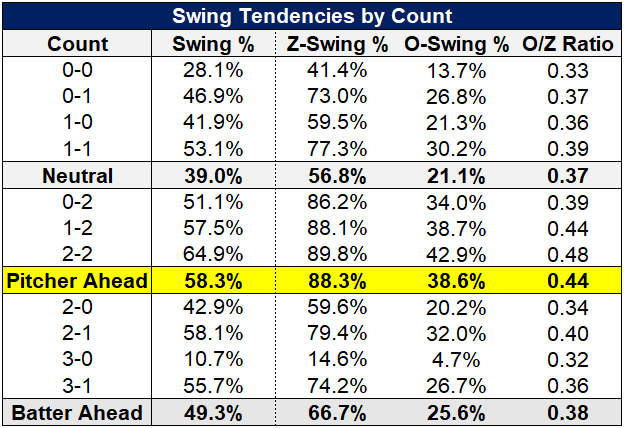

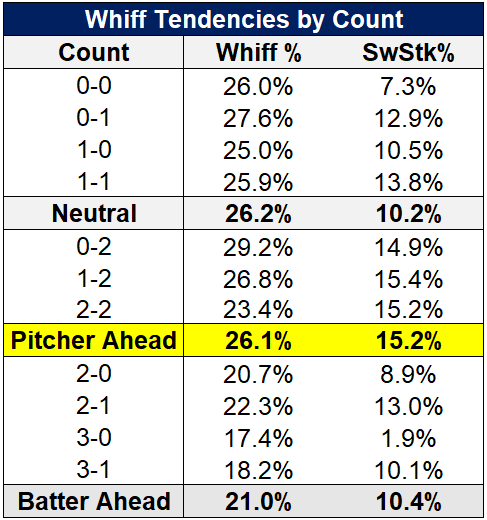

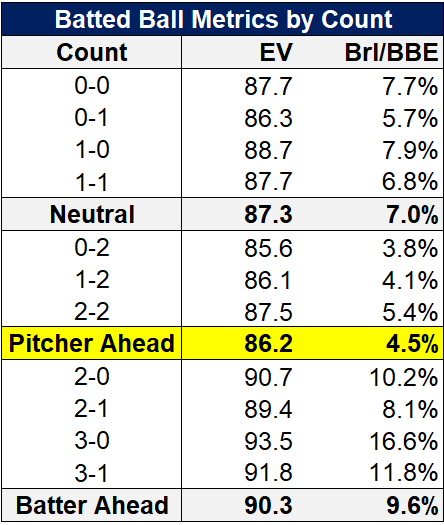

It doesn’t do justice do Nick’s article to summarize it with three charts, but these encapsulate the beauty of 2-Stk% extremely well. Essentially, the value exists in that, on average, hitters have extremely different tendencies depending on the current count of the at-bat in terms of both their behavior and their results.

What can we pull from this data? In 2-Stk counts, hitters will, on average, swing more both in and out of the zone, swing and miss more on a per pitch basis, and make much weaker contact when they don’t swing and miss. Additionally, when batters are ahead, they’re more selective with their swings, which means they don’t whiff nearly as much and put themselves in positions to optimize the contact they do make. All of this is fairly intuitive on the surface, but it’s eye-opening to see the concept illustrated in such a vivid manner.

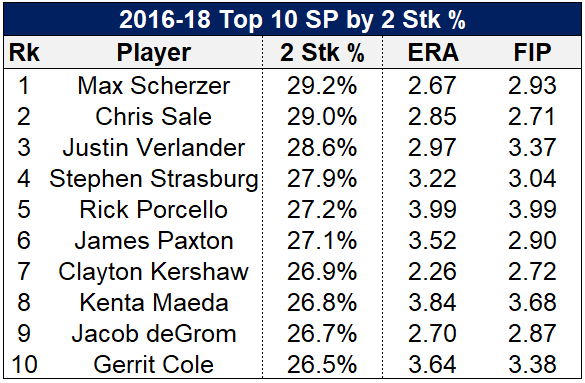

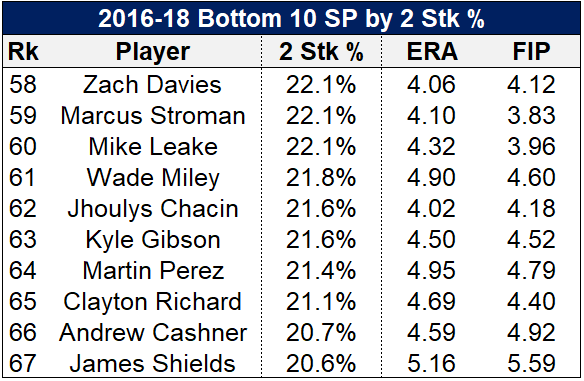

Nick’s findings then inspired him to look at 2018, and after finding second half risers such as Blake Snell, German Marquez and Trevor Williams with upticks in 2-Stk% that correlated to definitive breakouts down the stretch, he knew he had something brewing. That led to him grabbing a larger sample size from 2016-2018 with pitchers who had pitched a minimum of 400 innings and thrown a minimum of 5000 pitches. As you can see from the above graphic, the sample was quite telling. You have a who’s-who of Cy Young contenders up top, and zero pitchers with an ERA under 4.02 at the bottom. This was exactly the type of output you would hope for given the behavioral changes we covered earlier.

That being said, we still have an outlier up top: Rick Porcello.

What is it about Porcello that puts him on the border of a 4.00 FIP while the rest of the group sits from the mid-2’s to mid-3’s? Well the obvious observation is that the other nine starters are all elite whiff-getters, while Porcello is average at best, and that’s where our expansion of 2-Stk rate analysis begins.

It’s important to understand that no single stat can fully explain or forecast the performance of a pitcher. Pitching is complex and it relies on a combination of skills in order to establish a floor and a ceiling for the person doing it. So using different metrics in conjunction with one another will often paint a much clearer picture as to why a particular pitcher is getting certain results.

2-Stk Whiff%

When I first thought about how to best compare pitchers within the 2-Stk realm, I immediately looked to whiff rate, which is swings and misses per swing. I did this for a couple of reasons:

- I noticed that getting called strikes in 2-Stk counts was extremely difficult. Called-Strike% goes from 21.9% in neutral or hitter’s counts to a measly 4.3% in 2-Stk counts. This makes sense given our earlier recap where we identified the immense increase in both Z-Swing and O-Swing as hitters expand the zone when they fall behind. With this knowledge, I decided to create a tighter vacuum of comparison from pitcher to pitcher (which we do by reducing the sample from total pitches to total swings) to see who is still getting to strike-3 despite the fact that they will almost definitely need to whiff the batter to do so.

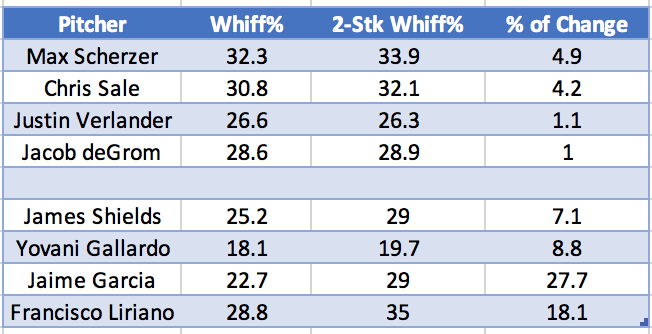

- We also know that on average, whiff rate, unlike swinging-strike rate, stays the same from neutral to 2-Stk counts, but plummets by about 20% (26.1% to 20%) in hitter’s counts. So, hypothetically, we can expect pitchers who are getting into 2-Stk counts frequently to have relatively similar overall and 2-Stk Whiff rates, while pitchers who spend less time in 2-Stk counts will have 2-Stk Whiff rates that outperform their overall whiff rate.

The second point was easy to surface check, as I took a large, stable sampling of pitchers from 2015-2018 and then took four of the best and four of the worst in 2-Stk% to compare their relative percentage of change from overall whiff rate to 2-Stk Whiff rate.

As we expected, the relative percentage of change for the elite 2-Stk pitchers’ whiff rates were pretty marginal compared to those of the worst 2-Stk pitchers. This is something I plan to study even further, but nonetheless, it provides a level of confirmation of our hypothesis from above and gives us a tremendous tool to spot potential regression candidates over smaller samples within seasons, which I will do for 2019 shortly.

The Big Picture

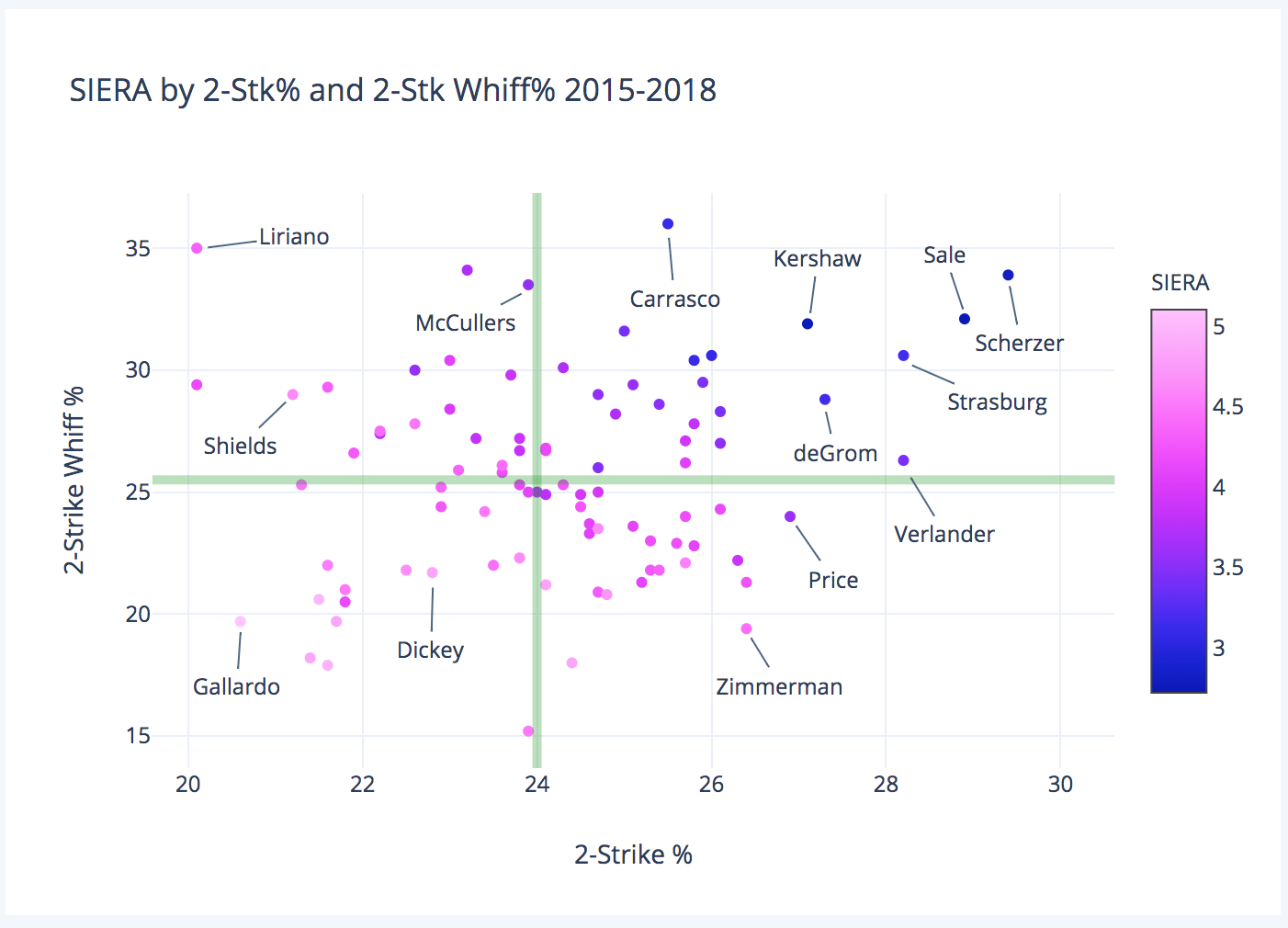

So, that 2015-2018 sample… it really tells the story well. The idea for the analysis is simple: see how the skills of not only getting to two strikes, but also finishing a hitter off with a whiff correlate to an ERA-estimator. I chose SIERA in order bring in just a little bit more ball-in-play analysis, as I found FIP to be a bit too volatile, given its hyper-focused formula looking at home runs, walks and strikeouts. The graph below plots a pitcher by 2-Stk rate and 2-Stk Whiff rate and then colors the dots by SIERA. The green lines create quadrants based on league averages for both statistics.

Immediately, we have a quite intuitive takeaway: being in 2-Stk counts and getting a lot of whiffs in those counts makes you a pretty good pitcher. However, the other important takeaway is that being good at one of these skills but not the other, does not inherently make you a good pitcher. David Price and Jordan Zimmerman are two great examples of this.

Both pitchers are known for their good control and clearly have an elite ability to work their way into friendly 2-Stk counts. Price works just below league average with his whiff rate, which, while capping his upside as a strikeout pitcher, still allows him to dictate at-bats and sit just inside the top 20 of SIERA for this time frame. Zimmerman is one of the worst whiff-getters in baseball, allowing hitters to stay alive more and often put the ball in play, which puts him just inside the BOTTOM 20 of SIERA for this time frame.

On the opposite end of the spectrum for 2-Stk rate, we get guys like Francisco Liriano and Yovani Gallardo. Liriano has demonstrated high upside over short stretches in the past, but has been a middling pitcher with poor control over the majority of the last four seasons. So when he gets into 2-Stk counts, he can be great, but he’s in them so infrequently that it basically doesn’t matter. Gallardo has been arguably the worst pitcher in baseball, and this is backed up here by him not only being incapable of getting into 2-Stk counts, but also being completely hopeless in terms of getting swings and misses even with the hitter at a disadvantage.

The 2019 Landscape

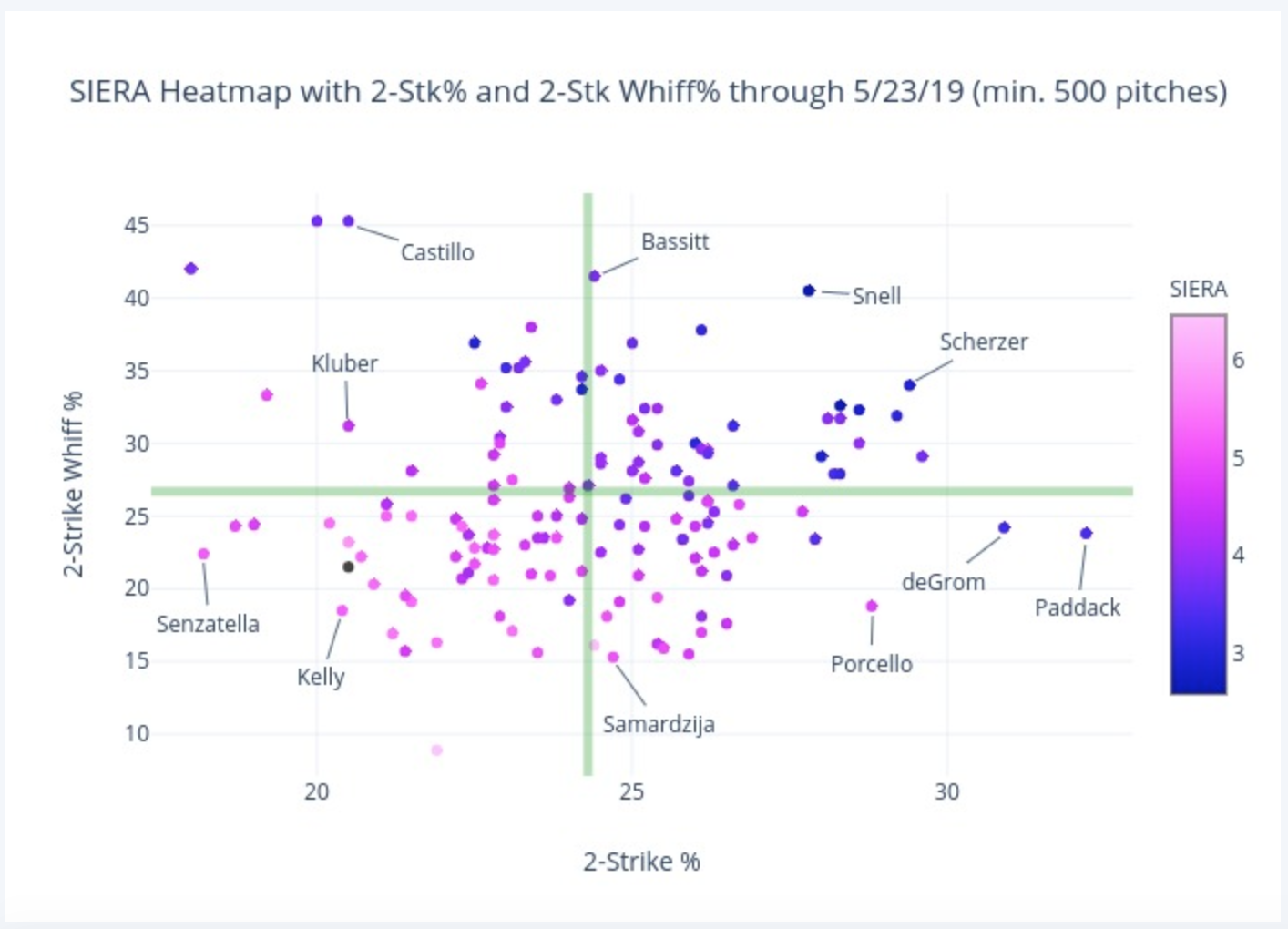

With the larger, stabler sample taken care of, let’s use what we’ve learned and apply it to pitchers in 2019.

Surprised? Fascinated? Relieved? Yea, me too.

The first thing that stuck out to me was Chris Paddack. He’s been incredible, and these peripherals support it. He’s a 2-Stk god amongst men. He’s sitting at a 32.2%, which is absolutely elite. It sits well above the high water marks of the past four seasons, but it still makes a ton of sense. We love Paddack’s fastball and the way he seems to fire in there like a sharpshooting sheriff. He is amongst the league leaders in CSW rate and it’s because of that pitch and how he’s able to consistently get ahead with called strikes.

Here’s where things get interesting for Paddack, though: he’s very much an average whiff-getter on a per swing basis. He keeps hitters off-balance, induces very weak contact, and gets a lot of foul balls with his pinpoint command, but he only has one truly developed secondary pitch, and that’s his changeup. On average, breaking balls (ex. curveball, slider) will have higher whiff rates than offspeed pitches (ex. changeup, split-finger) and both will have significantly higher whiff rates than fastballs. Paddack is insanely gifted, but with a heavy reliance on his fastball as an out-pitch and an underdeveloped (for lack of a better term) curveball, he is currently capped in terms of his ceiling compared to that of a super-ace like Blake Snell, Max Scherzer, or Chris Sale. Don’t get me wrong, he’s still an incredible fantasy pitcher (and real-life pitcher), and the future for him is extremely bright! As Nick Pollack would say, “he’s dope, and you should feel dope for owning him.” He has not had enough volume of innings as a professional to perfect his entire repertoire quite yet, but he will, and I don’t think we’re far away from him being in the “Best in Baseball” conversation.

Here are a couple more encouraging names who’s performances are supported by the 2-Stk realm in 2019:

Lucas Giolito (28.3% 2-Stk, 31.7% 2-Stk Whiff) – Oh, Lucas, you sneaky boy! Getting all good all of a sudden. Giolito’s breakout appears to be legit. He was actually the second biggest riser in 2-Stk% at the end of 2018 behind David Price (as pointed out in Nick’s original article), and he’s carried over that newfound approach into early 2019. He sits in that bundle south of Snell and north of Porcello and deGrom amongst names like Scherzer, Sale and Gerrit Cole and northeast of names like Caleb Smith, James Paxton and Clayton Kershaw. Like seriously, what is happening?? Giolito’s aggressive approach in the zone (56.1% zone rate is good for 3rd highest in the league, minimum 500 pitches) is clearly allowing him to either get ahead or battle back in most at-bats, and his slider/changeup mix is combining to make him a dangerous strikeout pitcher once the hitter is behind. This is all extremely exciting stuff.

The lone caution I spot with Giolito at the moment (at least peripherally) is that his 2-Stk Whiff rate is far superior to his overall whiff rate (31.7% compared to an overall 26.6%). Given how often he’s in 2-Stk counts, we would expect those numbers to be a bit more symmetrical, and I’m certainly wondering if he’s due for a bit of negative regression because of this. Do I think that it will impact him severely? No, I don’t. But he’s certainly someone you should be monitoring to see if his skillset levels off, slightly declines, or continues its upward trajectory.

Matt Boyd (26.6% 2-Stk, 31.2% 2-Stk Whiff) – There are quite a few Boyd Boys in the PitcherList community, and for good reason. This dude is good. His performance his backed up by both an above average 2-Stk rate and an above average 2-Stk whiff rate, helping him achieve the 12th best SIERA in the league. Boyd is fascinating. He heavily features an elite slider (35% of his total pitches) and yet he sits amongst the top 25 pitchers in terms of zone rate. He induces an above average rate of first-pitch swings, but a below average rate of first-pitch contact. On top of that, he has an average called-strike rate to go with an above average whiff rate and gets above average O-Swing that aligns naturally with his elite 2-Stk rate.

So Boyd keeps you honest, keeps you guessing and has good enough stuff to get considerable whiffs when you swing. Even if his 31.2% 2-Stk whiff rate regresses to meet his 29.6% overall whiff rate, you’re still looking at a pitcher who is sitting comfortably in the upper-right quadrant. To those of you who were doubting Boyd’s breakout, you can stop now. He’s a tremendous talent and he’s starting to make the most of his repertoire.

Now for a few names to be wary of:

Luis Castillo (20.5% 2-Stk, 45.3% 2-Stk Whiff) – I know! Weird, right?? Who would’ve thought that there was anything wrong with a guy who has a 14.9% swinging-strike rate, a 20% K-BB rate, a barrel rate that sits well below league average and an average exit velocity, xBA, and xSLG that all sit in the top 4% of the league?

Unfortunately, we do have things to worry about with Castillo. He is in the bottom 9% (!!) of 2-Stk rate. Of course this called for immediate investigation, and thus quite the level of evidence was found. Castillo is dead last in baseball in zone rate at an absolutely absurd 39.6%, and this is a consistent trait across all counts. When he’s in 2-Stk counts, he throws a mere 30.4% of his pitches in the zone. Is it fair for him to expect a hitter to expand the zone and chase in those counts? Absolutely. And with his absolutely devastating changeup, I don’t doubt that he can fool hitters as well as, if not better than, any pitcher in the game. This is blatantly evident by his virtually unmatched (only by reliever Corbin Burnes) 45.3% 2-Stk whiff rate. However, that 30.4% runs WELL below the league average 38.2% zone rate in 2-Stk counts, and Castillo continually lives outside of the zone in neutral counts (39.4%) and even sits at a mere 49.7% when he’s behind. In other words, if you’re in a 2-0, 2-1, 3-0, or 3-1 count, the odds of of Castillo throwing you a strike are currently less than 50%. That’s pretty crazy. And to make things even tougher on himself, his zone rate even on the very first pitch of the at-bat is 36.6%. He’s setting himself up to battle from behind the vast majority of the time.

Now, with all of that said, do I believe that Castillo is a bad pitcher? That is a HARD no. I think Castillo sits well within the top 20 SPs and probably within the top 15 in this current landscape. He sits amongst the very elite in everything from whiff rate to xwOBA and CSW rate. His changeup is clearly a special pitch, and he could certainly continue to dominate a lot of teams with his current repertoire and how he’s deploying it. However, it’s important for owners to recognize that he’s fragile. The sky is the limit when he is actually able to get ahead, but it looks like hitters are bailing him out quite a bit this season, and if they stop doing that, the floor is very low from start to start.

Castillo doesn’t just lack 2-Stk pitches, he leads the majors in pitches thrown in hitter counts (2-0, 2-1, 3-0, or 3-1). Knowing that he’s unlikely to throw them a strike and that even if he does, they will be in a count where he’s even less likely to throw them a strike, hitters have a very simple adjustment that they can make. They can put the onus on Castillo to truly challenge them in the strike zone. His 10.9% walk rate is the eighth worst in baseball right now, and if hitters become more patient and selective while facing him, that K-BB rate will continue to shrink and we could become spectators of some really poor outings for Castillo during the rest of the season. My advice? Sell him very high. Like I said, I think he’s possibly top 15 and certainly top 20, but if you can get a buyer to give you a top 5-10 SP type of return for him, I would do that deal in a heartbeat.

Yu Darvish (22.9% 2-Stk, 30% 2-Stk Whiff) – Yu sonaova #@&$%. Yu gotta be kidding me. Yu can’t be serious. All things that Darvish owners have likely muttered or straight up screamed this season. Well, bad news. It’s probably not getting brighter anytime soon. He’s dropped into a dangerous range with his 2-Stk rate at 22.9% and he doesn’t have a Castillo-like whiff rate to make up for his lost ground. He already sits below league average in zone rate at 47.4% and he’s one of the worst in baseball this season at actually getting to an 0-1 count at 45.2% (90th of 99 pitchers with at least 200 at-bats against). So he doesn’t throw the ball in the zone very much, he’s usually working from behind, and then he relies on breaking pitches to get himself back into competitive counts. Darvish’s fastball has been very bad in 2019, and as a result, he’s been leading with his cutter in May (179 cutters and sliders vs 177 total fastballs). He’s pretty much junk-balling at this point with an inconsistent approach and a heavy dependence on the hitter to swing.

His batted-ball data and his strikeout rate may seem encouraging, but he’s walking hitters at an almost unbelievable 16.6% clip. When a combined 45.2% of your opponents aren’t even putting the ball in play early in the season, your batted-ball data is going to be volatile and potentially skewed. The only pitcher spending more time in hitter counts than Darvish with a minimum of 500 total pitches is Castillo, and when you live in those counts, you subject yourself to more selective swings and better contact from the hitter. If he maintains this early count approach, Darvish is either going to continue ballooning your WHIP with his insane walk rate or he’s going to be at risk of giving up more hard contact and more barrels. Either way, he has a lot to change before he can be trusted again.

Now, his CSW rate sits at 30.3% and it’s because he’s continuing to show an elite ability to get swings and misses despite having a somewhat incomplete repertoire. Additionally, he has two likely directions he can go in terms of his 2-Stk performance and they’re both positive. Either he finds a way to get ahead more consistently and increase his 2-Stk rate to move toward that upper-right quadrant of our graph, or he sees his 2-Stk Whiff rate regress positively. He’s currently holding a 30% 2-Stk Whiff rate compared to a 32.2% overall Whiff rate, and given his below average 2-Stk rate and our theory from earlier regarding the difference in the two whiff rates, it would not surprise me to see his 2-Stk Whiff rate close the gap and eventually surpass his overall whiff rate by quite a bit (assuming his 2-Stk rate remains the same). So, should you own Darvish? Yes, I think keeping him stashed is a fair play. Should you start him? No. Regardless of matchup, I just do not see enough from Darvish to trust him at the moment. Cross your fingers and tread lightly.

Key Takeaways

So what have we learned?

- 2-Stk rate and 2-Stk Whiff rate on their own are not enough to fully forecast a pitcher’s success. Using them in conjunction is what allows us to establish a range of outcomes for a given pitcher.

- Even these two statistics don’t paint the full picture. A big part what I covered was the comparison of 2-Stk Whiff rate and overall whiff rate in order to seek out potential regression. Use the 2-Stk realm to seek out potential diamonds in the rough and then kickstart a deeper dive to see if that pitcher’s current performance is sustainable or not.

- Don’t forget about CSW rate! It’s just as robust at 2-Stk rate in terms of forecasting a pitcher and it tells a complimentary story. CSW rate provides us with a baseline of knowing how capable a pitcher is at getting contactless strikes in the first place. Remember, even without an elite swinging-strike rate, pitchers can still consistently work their way into 2-Stk counts with good command to set themselves up for a higher likelihood of swinging-strikes. A high CSW rate will reflect a level of efficiency and reliability in the approach of a pitcher that we do not want to ignore.

2-Stk rate will be a focus for both me and Nick Gerli over the course of the season, and we hope to slowly dial in its applicability to help all of you in the near future and beyond.

(Photo by Jimmy Simmons/Icon Sportswire).

Where does Kyle Gibson land in this sort of analysis? Seems like an arm with measurable improvement, he has the prospect pedigree, is he severely undervalued? And what are your thoughts on him moving forward? Thanks this article was fantastic!!

Great question, Clayton! Gibson is certainly a fascinating guy by these metrics. Last season, he sat VERY low in 2-Stk% (22.0%, well within the outliers at the bottom of the spectrum). He was able to find balance by sitting as a positive outlier on the 2-Stk Whiff% scale.

One of the things that I pointed out above with Darvish was that he’s playing with fire because he’s trading off high walk rates for decent batted ball data (something you have to do when you’re constantly behind and rely on breaking pitches and a low zone rate). Gibson did something similar last year by staying below league avg in barrel% while being above league average with walk rate. Well, this season, Gibson as improved his 2-Stk% to a rate just below average with an insanely (and quite possibly unsustainable) 38% 2-Stk Whiff%. His walk rate is significantly down, but now his batted ball data looks a lot worse! So again, we see an example of how being below average is 2-Stk rate creates fragility for a pitcher, because he’s constantly having to work from counts in which he’s at a statistical disadvantage. Gibson relies heavily on his slider and spends a lot of time outside of the zone. He doesn’t have a good enough fastball to battle back in counts. Again, he’s very good in 2-Stk counts when he can get there, but he’s not in them enough for it to move the needle. Track his 2-Stk% throughout the season and see if he things change! But my guess is that he’ll probably continue to be a guy to deploy against weak lineups with confidence and sit in situations where you don’t have to risk it.

Just the kind of analysis i was looking to read. Love the knowledge and thought you put behind your words. Thanks!

Great work!

Taking your analysis at rudimentary face value, would you swap Castillo for Paddock straight up? Would it be close?

Thanks Jake! That question has a range of answers depending on league details. In a redraft league, I’m probably holding Castillo, as there’s still a significant chance Paddack has more “stiff necks” throughout the course of the season (if you catch my drift). The Padres will not want to challenge his volume. Castillo is still a dominant arm with immense upside this season, and I would rather stick with him than risk possibly getting a mere 50-70 more innings out of Paddack this year. In keeper and dynasty leagues, I personally like Paddack more. I think his approach is way more sustainable, as he’s a true strike-getter with pinpoint competitive command, not simply a whiff-getter. As he matures, I expect him to be one of the very best.

This revelation is called protecting with two strikes. Any hitter could tell you that they swing more with two strikes. Id imagine that list of k/9 leaders looks a lot like 2 strike swing rate leaders. I would expect a rate like this to be skewed towards breakouts as thier pitch mix is not as well understood which is unsustainable.

Never said this was a revelation. We aren’t discovering baseball. We’re statistically representing skillsets that we know intuitively lead to success.

As for the K/9 leaders looking a lot like 2-Strike Whiff% leaders, I don’t doubt it. A lot of these pitching statistics will correlate strongly to one another. Increase in SwStr will strongly correlate to increase in K/9, which will correlate strongly to increase in K%, which will correlate strongly to K-BB%, which will correlate strongly to FIP, which will correlate strongly to ERA. Everything is connected. But the goal should always be to find enough high-level statistics to streamline our analysis and set ourselves up for quick comparisons. 2-Stk% tells me how capable a pitcher is at getting strikes that aren’t balls in play while simultaneously giving me a foundational expectation of what his batted ball data should look like. 2-Stk Whiff% gives me an illustration of a pitcher’s upside and can be used in conjunction with 2-Stk% to spot regression through comparison to overall Whiff%. With that knowledge, I now know exactly what a pitcher SHOULD look like peripherally and compare that to what he is.

As for 2-Stk% being “skewed toward breakouts”, I’m not sure exactly what you mean by that. Do you mean that a pitcher who significantly changes his approach or is young and unseen will perform well in the 2-Stk realm? I mean his approach would have to be a good one, but sure. Again, you have to get to 2-Stk counts first before you can exploit the advantages of being in them. It’s absolutely true that hitters could adjust to a vulnerable aspect of an approach (say, jumping on first pitch meatballs with a guy who sits in the zone on 60-80% of first-pitches), but if you can get to 2-Stks, that tells me you’re getting a second strike in the at-bat quickly, which is hard, and if you have a high 2-Stk Whiff%, that tells me you’re very capable of getting a third strike, which is the the hardest one to get. Once we’ve established an ability to be proficient in both of these skills, simply “adjusting to the pitch mix” is much easier said than done. That pitcher does a lot of things extremely well, so where do you start? They aren’t fragile.