General Manager Andrew Friedman had the third pick in the 2006 MLB draft. For a team like the Tampa Bay Rays, the laughing stock of the league for years up to that point, the importance of nailing that pick was crucial. The Rays selected Evan Longoria from California State University, Long Beach, to be their franchise third baseman. At 6’1″ and 210 pounds, Longoria easily fit the part of stalwart at the hot corner the Rays desperately needed. He soared through the minor leagues and made his debut April 12, 2008. It did not take long for Longoria to become the face of the franchise, as he became an integral part of the upstart Rays that went to the World Series—an improbable feat considering a year earlier Tampa lost 96 games.

As the years went on, Longoria continued putting up nearly 30 home runs and 100 RBI every season and was rewarded with a handsome extension by Tampa standards—potentially worth $144.6 million over 11 seasons. But starting around 2014, Longoria’s production dipped toward the level of an average hitter, and with the exception of a resurgent 2016 campaign, continued at that pace until he got sent off to the San Francisco Giants just before the 2018 season. As his 2018 campaign resulted in his lowest wRC+ of his career, 85—15 percent below average—the baseball universe officially wrote off Longoria.

This season, Longoria’s production has only equated to a 100 wRC+—a league-average hitter—so it would seem that he’s continued on his recent mediocre track. Though if you scratch under the surface, you’ll find quite an intriguing story.

Young, Wild and Free

Longoria always had an unbelievable ability at the plate, never struggling in the minor leagues and then continuing to mash in the big leagues, hitting 162 home runs over his first six seasons, including 17 over an injury-shortened 2012 campaign in which he only played 74 games.

This was a result of his pure, easy swing. In an open stance, he would drift toward the plate and fire his hands through the zone, and the ball would jump off the bat.

Here is Longoria’s first postseason home run his rookie season:

That same smooth, pleasant swing led to powerful results.

| wRC+ | ISO | HR/FB | |

| 2008 | 128 | .259 | 19.4% |

| 2009 | 132 | .245 | 17.6% |

| 2010 | 139 | .213 | 11.1% |

| 2011 | 136 | .251 | 17.6% |

| 2012 | 146 | .238 | 19.5% |

| 2013 | 132 | .230 | 15.7% |

Despite the great production in his first six seasons, Longoria seemed to develop some bad habits. Look at these swings, the first from 2011 and the second from 2013:

Just prior to getting into his load position, Longoria has a little wiggle in his bat. Considering he already has an open stance, any lag in his bat path would disrupt his timing. The wiggle is not that prominent in those swings, but any sort of exaggeration of that movement would have an extremely negative impact.

Who Am I?

During this period, Longoria fell from one of the most productive hitters to generally an average hitter. This is a direct result of our earlier discussion. Here we’ll look at some home runs from 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively:

In 2014, Longoria seemed to have adopted a completely different stance. He was fairly erect in stature, while in past seasons he generally had a slight dip in his legs. That was an additional problem in his decreased power numbers. The following season Longoria corrected that issue, sitting more in his legs. We can also see Longoria has a much more open stance, similar to earlier in his career. The only issue is that there is now a more prominent hitch, which makes it problematic for his timing and getting into his load position. In 2016, he closed his stance again while reverting to standing relatively upright. That combination clicked, as he was able to overcome the hitch in his swing—resulting in his best season in several years with a 123 wRC+.

However, in his 2017 and 2018 swings, things seemed to get worse.

In those two swings, you’ll notice that his bat head ended up pointing directly toward the pitcher, and then he brings the bat all the way back toward his load position. In the past, it was not nearly as drastic. He was able to use the closed stance to negate a less severe hitch, but it then reached a point where he was late on his load and had to compensate.

| Contact% | ISO | HR/FB | |

| 2008-2016 | 77.2 | .219 | 14.9% |

| 2017-2018 | 80.9 | .166 | 10.6% |

Longoria ended up trading power for contact derived from his inability to get his hands in the right position. This made him a far less potent hitter, aiding his career-low output.

Drop It Like It’s Hot

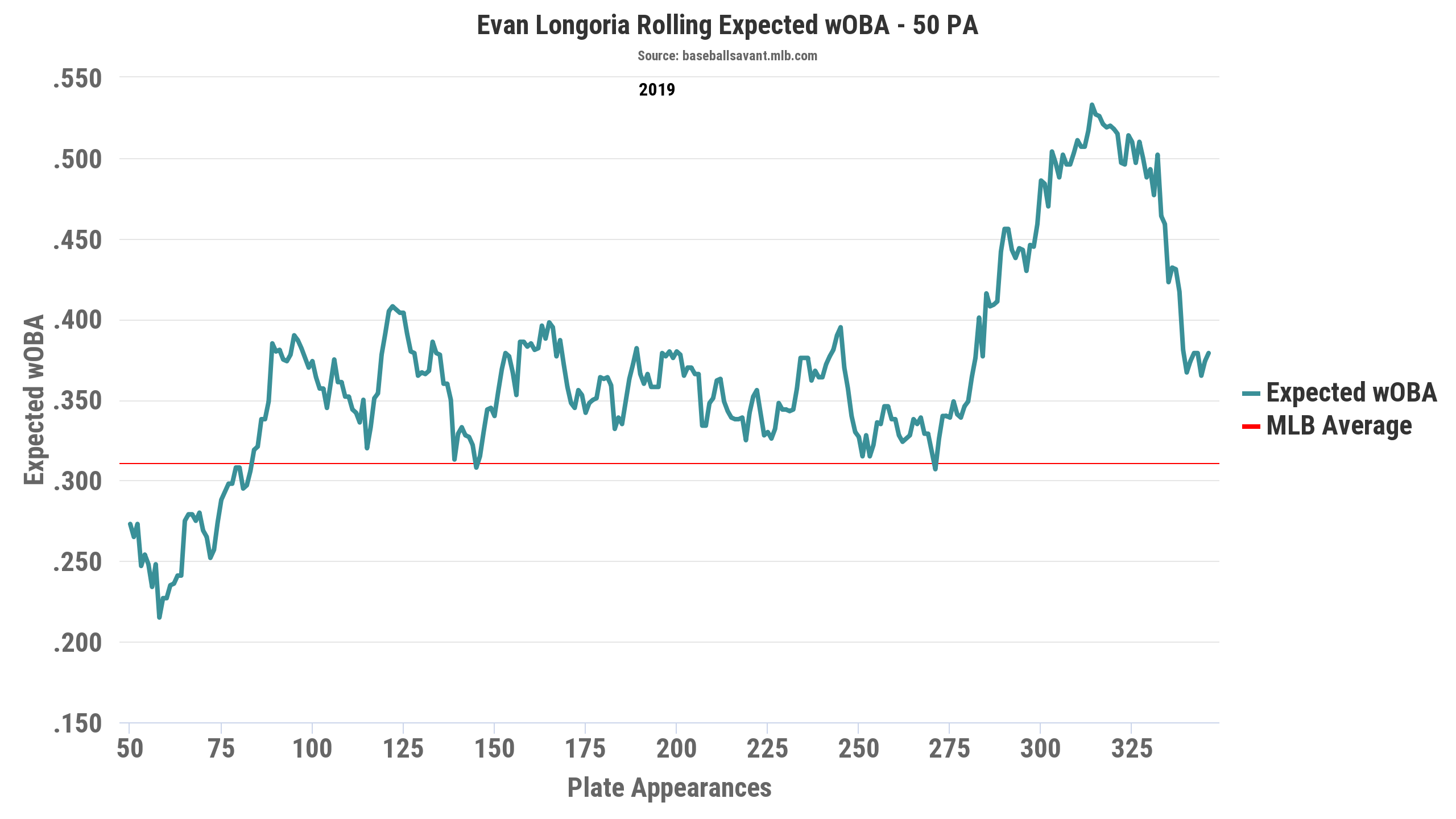

This season, Longoria has reached new heights after a fairly slow start to the season.

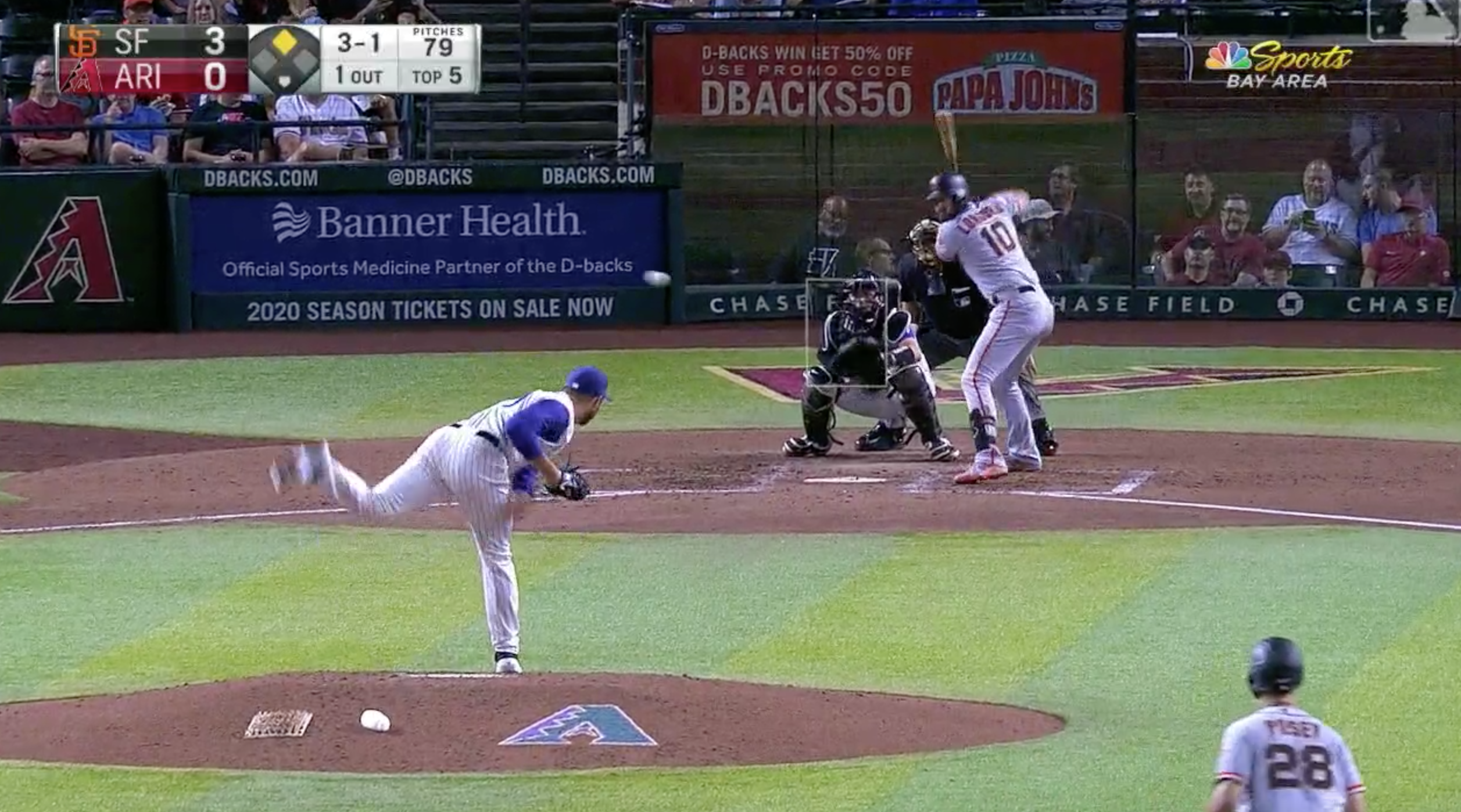

This coincides with Longoria breaking out his trademark swing—displayed as recently as Thursday:

Longoria has taken out some of the bat inefficiencies prior to loading, which has helped a ton with his timing. This has allowed him to open up his stance a little more, bringing back some of the rhythm he used to have back in his heyday. Just look at where his bat is just prior to swinging compared to last season:

2018

2019

His bat is much higher, where the bat head is pointed up and coiled behind his head just a little more this season. This results in increased ferocity in the swing, thus getting the desired power. This all comes from having the time to get into a power position.

Clearing up some of those hindrances have helped Longoria see a marked improvement from last season in power, reversing the trade-off he made the past two seasons.

| Contact% | ISO | HR/FB | |

| 2019 | 77.9 | .198 | 15.9% |

The confidence Longoria has shown at the plate has made him a much more destructive force and that’s a great sight to see after such a tumultuous period.

Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang

Longoria took a while to get back to his old form, but it seems he’s finally reached it—in terms of hitting ability. His wOBA is .327, reflecting middling production. For as bad as his wOBA statistic is, it’s really just a case of bad luck. Longoria’s xwOBA of .361—nearly identical to his .362 xwOBA in 2016—reflects a negative differential of .034 between his wOBA and xwOBA, which is the 22nd-largest negative differential in MLB among hitters with at least 100 plate appearances this season.

Why is there such a large discrepancy? The answer is San Francisco. Look at his splits between home and away this year:

| ISO | xISO | |

| Home | .128 | .173 |

| Away | .284 | .281 |

| Overall | .198 | .221 |

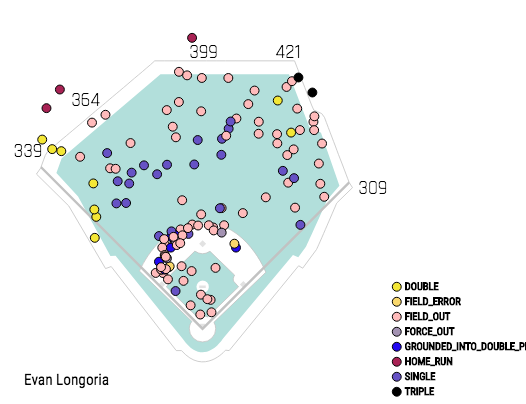

Not that Longoria has been lighting it up at home, either, as seen from his expected ISO, but it’s still far higher than his actual number. You can see from his spray chart of the balls he’s hit this season what issues he might have.

Look at the number of fly balls that end up on the warning track that die out there—particularly in Triples Alley. The right fielder is generally shaded toward right-center for that reason. If you add the fact that San Francisco at night has fairly dense air with lots of wind, a lot of those balls could be extra-base hits anywhere else.

If Longoria were playing somewhere else, maybe his numbers would reflect a player who was not going under the radar, but rather the prominent, recognizable force he’s always been.

(Photo by Justin Fine/Icon Sportswire)