When you play for large-market teams, you’re put under a microscope. That’s just how it is. For most of his career, Joe Kelly has pitched for the Boston Red Sox, and this year, he’s pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Lately, he’s been more apt to making headlines for brawls than being a force on the mound, because, by results, he’s been more ordinary than elite. Although he’s been a 3.50 ERA and FIP reliever over his career, Kelly is someone who has never seemed to get everything out of his skill set. In any case, he received a contract over the offseason that makes him the 22nd highest-paid reliever by average yearly contract. I would describe his contract as extortionate, but he currently makes more annually than names like Brad Hand, Blake Treinen, Ken Giles and Felipe Vasquez. Presumably, the Dodgers figured they could squeeze a little more production out of him, as they often do with players. Until more recently, that hasn’t been the case, and Kelly has been heavily criticized for his early-season performance.

Coming into this year, the Dodgers immediately had Kelly tinker with his arsenal. He completely ditched his slider and increased his changeup usage. It was…not a good change. How bad was it?

Kelly, through May 28th: 5.56 FIP

After a few months, the Kelly signing looked to be a disaster, albeit a relatively minor one. On the year, Kelly doesn’t have menacing numbers. In fact, by ERA and WAR, you wouldn’t think that anything has changed. That’s because, as you can see above, for two months Kelly was bad, but then, for two months, Kelly has been pretty great.

Kelly, since June 2nd: 2.11 FIP

Similar to many players, his yearly numbers are somewhat misleading. Let’s take a look at Kelly’s past two years, versus his past two months:

| IP | ERA | FIP | xFIP | K-BB% | |

| 2017-2018 | 123.2 | 3.64 | 3.53 | 4.05 | 11.7 |

| Through 5/28 | 18.1 | 8.35 | 5.56 | 4.03 | 11.2 |

| Since 6/2 | 21.2 | 1.66 | 2.11 | 2.43 | 27.0 |

We’re comparing between a large sample, and two smaller samples. There’s a chance that this is a blip—this is a mere 21.2 innings of dominance—but I’m not convinced. There are more substantial changes than a simple shift in pitch usage. And plus, for Kelly, this is pretty unprecedented. I’ll show you what I mean.

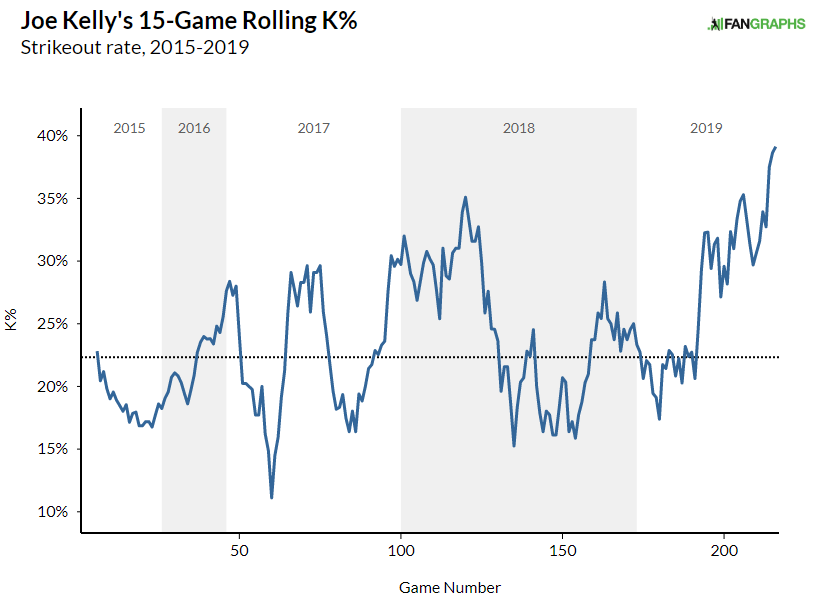

Kelly’s rolling strikeout-percentage:

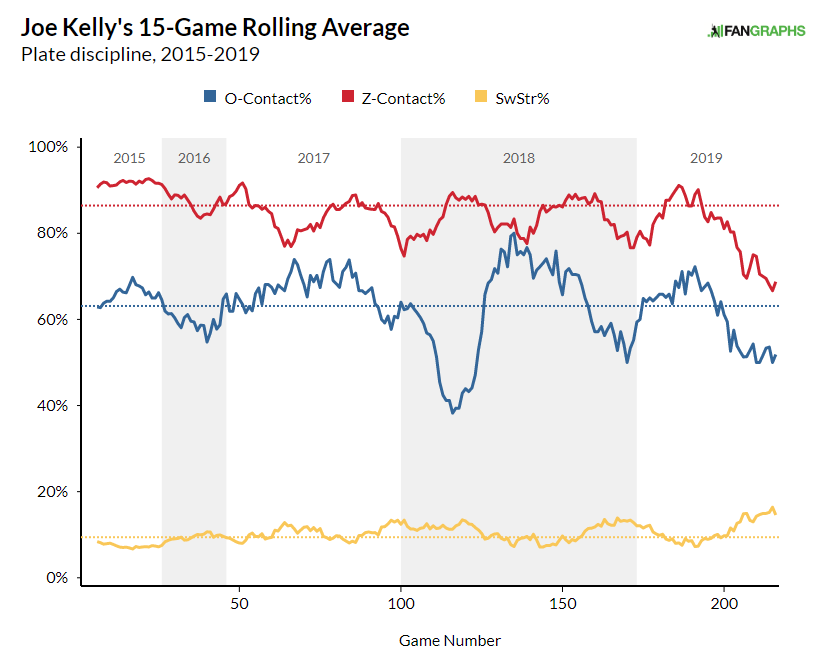

Kelly’s rolling outside-contact, zone-contact and swinging-strike percentage:

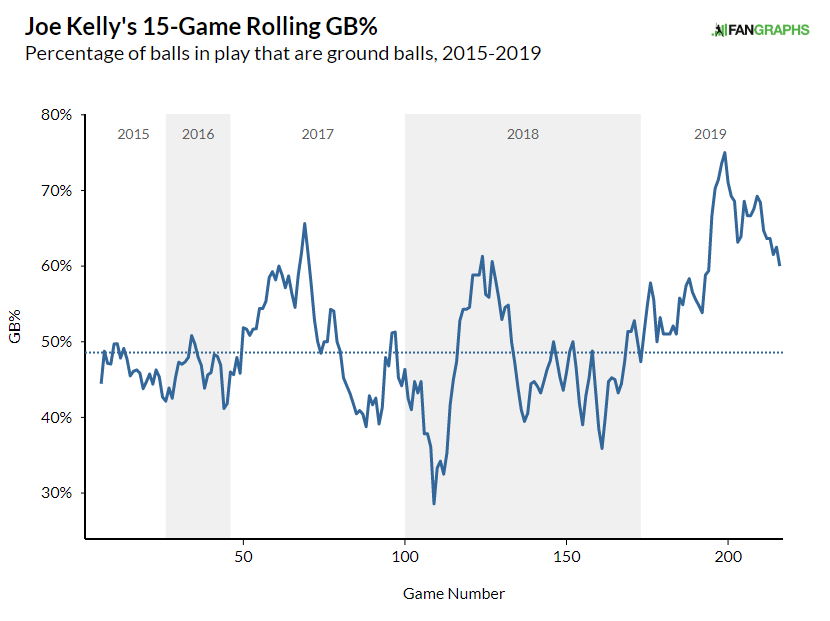

And lastly, Kelly’s rolling ground-ball percentage:

Here, we have five metrics that have all been moving in the right direction. We’ll get to it all in due time, but it’s encouraging that there are concrete changes to support all of these outcomes, and that helps to believe in the sustainability of Kelly as a greatly improved reliever. If we want to look at next-season sustainability, xFIP and SIERA will be the metrics we’ll want to use. But since SIERA has far more inputs, it’s safe to say that xFIP is the superior option here. It’s a cheap, reliable way to look at the projectability of a smaller sample. Since June 2nd, Kelly ranks 3rd among relievers by xFIP. That’s a touch below Kirby Yates and a touch above Liam Hendriks. Kelly is in good company, and it all starts with his curveball.

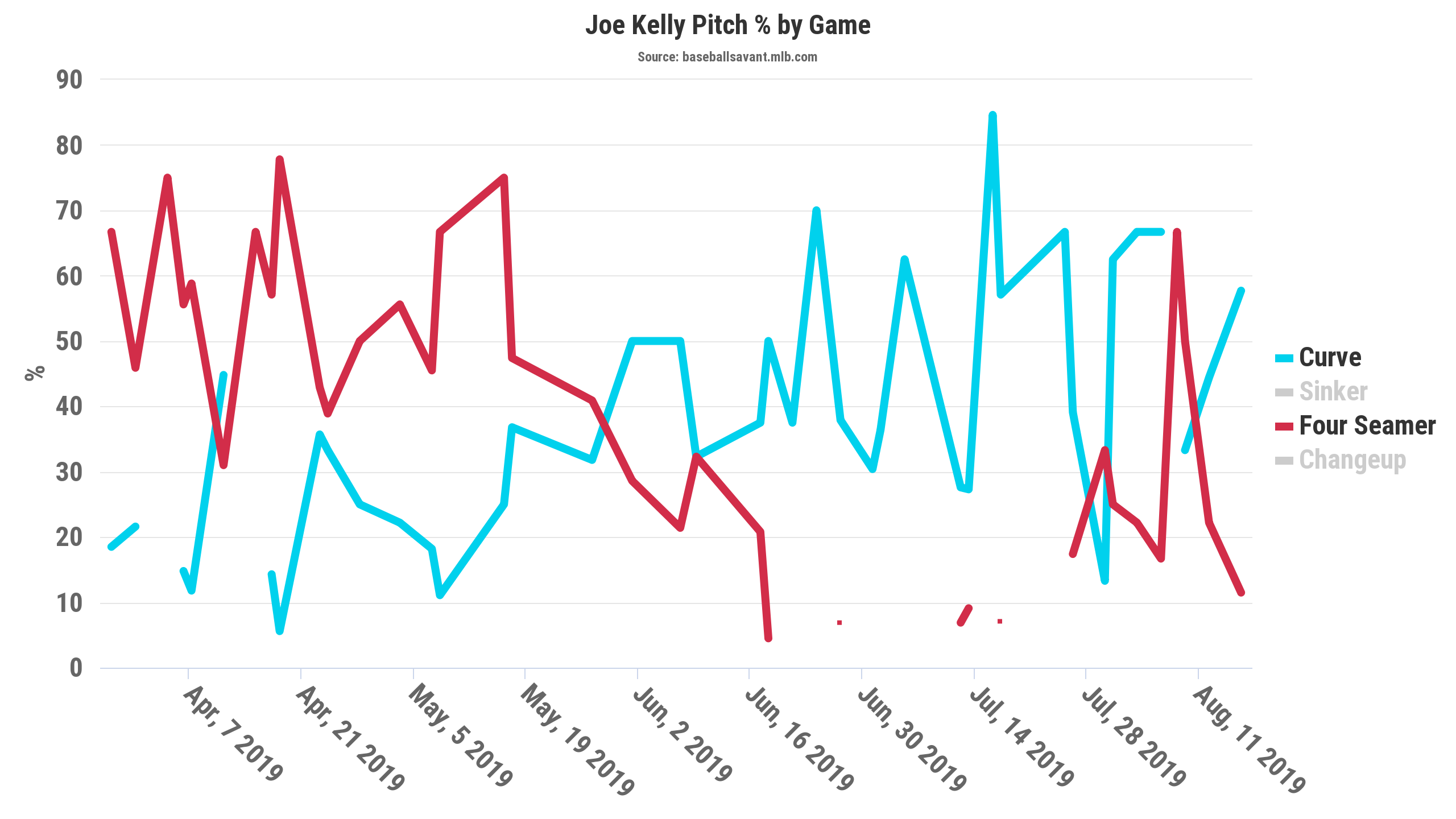

Starting in June, Kelly began to fade his fastball in favor of his curveball:

Sometimes, pitches produce mediocre results despite the fact that they’re good pitches. We know that Kelly has started to factor in his curveball far more, but he hasn’t done much in the way of where he’s locating his curveball. Plus, a change in curveball usage isn’t all that compelling as the sole reason for his improvements—over his career, he’s accumulated a -1.4 pVAL on his curveball, and that’s factoring in the 4.2 pVAL he’s added onto that this year. So clearly, there’s more here. What gives?

His curveball has changed! A table, comparing speed and movement profiles of his curveball, from 2017-2019:

| Velo | H-Mov | V-Mov (w/ gravity) | |

| 2017 | 84.4 | 3.2 | -45.6 |

| 2018 | 84.9 | 5.7 | -48.1 |

| 2019 | 87.1 | 5.8 | -43.7 |

So, he’s added velocity, while losing some vertical movement. Perhaps most importantly, he’s reduced his fastball-curveball velocity differential from about 14 or 15 mph to about 10 mph. While his pitch tunneling metrics don’t seem to have improved, apparently his velocity differential is more important. In hindsight, maybe this makes some sense. It’s difficult to catch up to upper-90s heat as is, but that becomes harder when the gap closes between one’s fastball and breaking stuff. As the year has progressed, that gap has started to close even more for Kelly, too. His curveball velocity has begun to revert towards his velocity from the beginning of the year (i.e., 86-87 mph) more recently, but his curveball was sitting 89 mph in the middle of July, and he’s touched 91 mph with his curveball too.

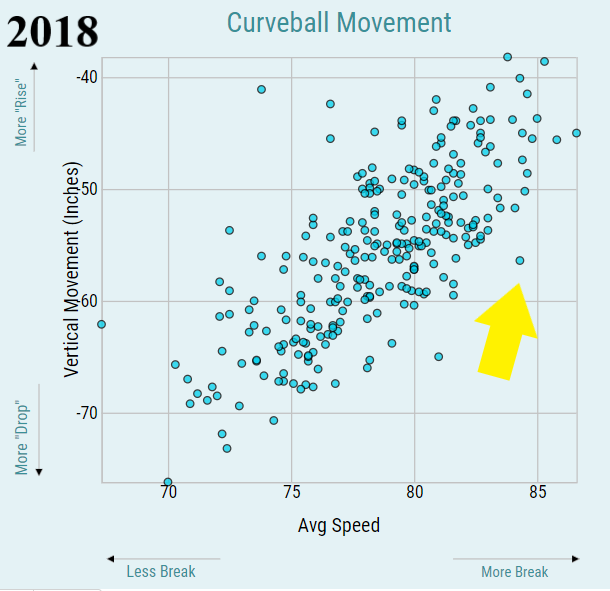

Here, we have a group of qualified curveballs (plotted by vertical movement and velocity) with Kelly’s curveball denoted by a yellow arrow, in 2018:

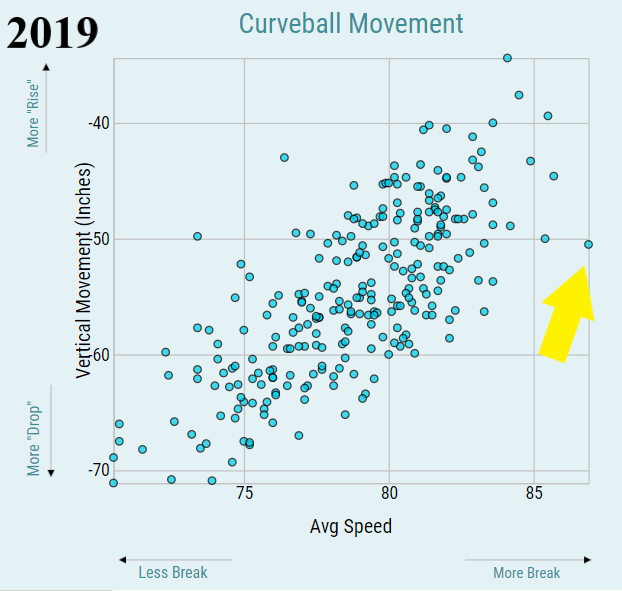

And here, we have the same thing, this time in 2019:

You’ll notice that, in 2018, Kelly had a rather unique curveball. In 2019, though, I’d argue that Kelly’s curveball is in a league of its own, aside from Matt Barnes‘ curve. But even then, Kelly’s curveball bests Barnes’ by two ticks, and that’s a pretty considerable amount.

Kelly has seemingly perfected a blend of elite curveball velocity, but with movement too. Historically, no one has really done this. There’s one player who’s done it recently: Craig Kimbrel. Here, I’ve compared velocity and vertical movement between Kelly (2019) and Kimbrel (2015-2018):

We can compare them solely by movement, too:

In becoming more akin to Kimbrel, Kelly has flourished. Yet, I have yet to say just how strong of a pitch his curveball has been this year. From 2015 to 2018, Kelly had a CSW of 34.4% on his curveball, which is pretty solid. This year, though, his curveball’s CSW has risen to 42.7%, which, by CSW, makes it the best curveball in the league. Next is Hyun-Jin Ryu’s at 41.9%. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Kelly’s 42.7% CSW on his deuce is remarkably Kimbrelian—Kimbrel posted a 43.4% CSW on his curveball from 2015-2018, which is the best in that time frame. It should be clear by now, but Kelly’s become quite a stud. At 31 years of age!

So by velocity, we see similarities between Kelly and Kimbrel, but then by movement, we can see similarities too. I’m sure you’re wondering: if Kelly’s pitches have the same velocity and the same movement, he could conceivably pitch like peak Kimbrel, right?

Well, there’s one thing that Kimbrel has that Kelly does not:

Kimbrel, 2015-2019 fastball spin rate: 90th percentile

Kelly, 2019 fastball spin rate: 22nd percentile

Despite the big velocity, this is the thing that has always stopped Kelly from being more dominant. Interestingly, Kelly’s fastball has historically gotten fewer whiffs than fastballs similar in shape and velocity to his.

Using Alex Chamberlain’s PITCHf/x database, I pulled four-seam fastballs from 2015 that had the following qualities: velocity above 95 mph, spin rate between 2,000-2,300, vertical movement below 18.0 inches and horizontal movement greater than -6.0. Kelly’s underwhelming 7.6% swinging-strike percentage ranked 11th out of the 17 pitchers, right with the likes of German Marquez, Nathan Eovaldi, and Jon Gray, which isn’t great. This year, his heater has gotten even worse—his four-seamer’s swinging-strike percentage has plummeted to 5.0% and he’s posted a 26.1% CSW with the pitch on the year. That’s well below average and about the same as Corbin Burnes‘ fastball…yuck. This is, perhaps, one reason Kelly has turned to his sinker as the year has progressed.

And maybe he should continue to switch out his sinker in favor of his four-seam fastball. On the year, he’s been throwing his sinker one mph faster than his four-seam fastball and it’s been one of the best sinkers in the league. That’s not hyperbole: his 36.4% CSW on his sinker ranks third in a sample of 152 players and by xwOBA (.257), it’s been a great pitch as well. This could be simply no more than small sample size, but one could speculate that it’s legitimately a better pitch now because it forms a stronger tunnel with his other pitches. After all, his sinker has been a better pitch than in 2017, when he threw it a touch harder. In any case, we should see him continue to turn to it because he’s had more success commanding it than his four-seam fastball. It should come as no surprise, then, that Kelly’s control has correlated with his sinker usage this year.

Related to his sinker, I want to refer back to the beginning of this piece,when I mentioned that Kelly’s ground-ball rate has risen. This is one thing of many things that makes me optimistic about Kelly going forward, but there are a few different (yet similar) things going on.

First, his pitches are all starting to become more groundball-heavy. Most notably, his curveball has seen a significant increase in ground-ball percentage from a career 64.0% to 75.0% this year. That makes it the most groundball-heavy curveball in the league and it gets whiffs too. His four-seam fastball is also inducing a few more ground balls than usual, and his sinker and changeup have also seen drastic increases in ground-ball percentage, relative to his career averages.

Second, he’s starting to use groundball-heavy pitches more. He’s the sixth-most groundball-heavy pitcher on the year and fifth most since June 2nd. He’s never going to be Zack Britton in terms of being a worm-killer, but it’s hard not to feel good about a pitcher who induces whiffs and balls beat into the ground.

Ultimately, there’s a compelling argument to be made that Kelly is becoming something of a relief ace. I’ll admit that there’s also one significant hole in that argument: he hasn’t pitched in huge spots. Since June 2nd, he ranks in the 35th percentile by pLI (pitch leverage). The counterargument here is that by WPA/LI (i.e., context-neutral), Kelly ranks in the 88th percentile. In any case, Kelly is set to get more save opportunities moving forward and so this argument should be somewhat resolved by the end of the year.

Since June 2nd, Kelly has been one of the best pitchers in the league. By xwOBA, he’s been the best pitcher in the league. What’s most encouraging is that there are reasons why he’s been so effective. It’s not yet clear what kind of pitcher Kelly is going to end up being, but it seems clear that he’s going to be quite a good one. At the end of the day, he isn’t exactly threatening Kenley Jansen’s job—and I have my doubts that this would ever happen— but at this point in their careers, maybe he should be.

Featured image by Nathan Mills (@NathanMillsPL).