As a writer, I’ve come to like writing about pitchers more than hitters. Hitters are fun—I can’t complain about writing Christian Yelich articles—but you wouldn’t believe how interesting and labyrinthine it is to analyze pitchers. Subtle changes can net gigantic improvements, and there are endless amounts of changes pitchers can make. As you’d have it, Lance Lynn is making changes, and he might be catching a second wind at the age of 32. Seriously.

For over a month now, Lynn has been doing this:

| IP | K-BB% | ERA- | FIP- | xFIP- | |

| Last 9 games | 59.1 | 26.5 | 68 | 55 | 69 |

Now, Lynn pitched against the Royals twice, it’s true, but he also was tasked with the Athletics, Astros, and Red Sox, and performed admirably. Lynn has had streaks of dominance before, but he’s never seen this level of dominance in the Statcast era.

Here’s how starting pitchers have stacked up against Lynn since May 21st:

| K-BB% | ERA- | FIP- | xFIP- | WAR | |

| Lance Lynn | 28.4 | 73 | 41 | 64 | 2.2 |

| Max Scherzer | 31.7 | 20 | 38 | 68 | 2.0 |

| Chris Sale | 31.0 | 53 | 43 | 57 | 1.7 |

| Walker Buehler | 32.9 | 46 | 56 | 55 | 1.5 |

| Hyun-Jin Ryu | 18.4 | 22 | 51 | 69 | 1.5 |

In just over a month, Lynn has accumulated 2.2 WAR, which leads the MLB in this time frame. I will admit, the ERA (3.57) isn’t pretty, and he has the advantage of having pitched an extra game over the latter four pitchers, but his .315 wOBA is incongruent with his .291 xwOBA, so that may mean Lynn has been better than his ERA, as his predictors indicate. Regardless, this is awfully impressive. Again, this is Lance Lynn we’re talking about, people!

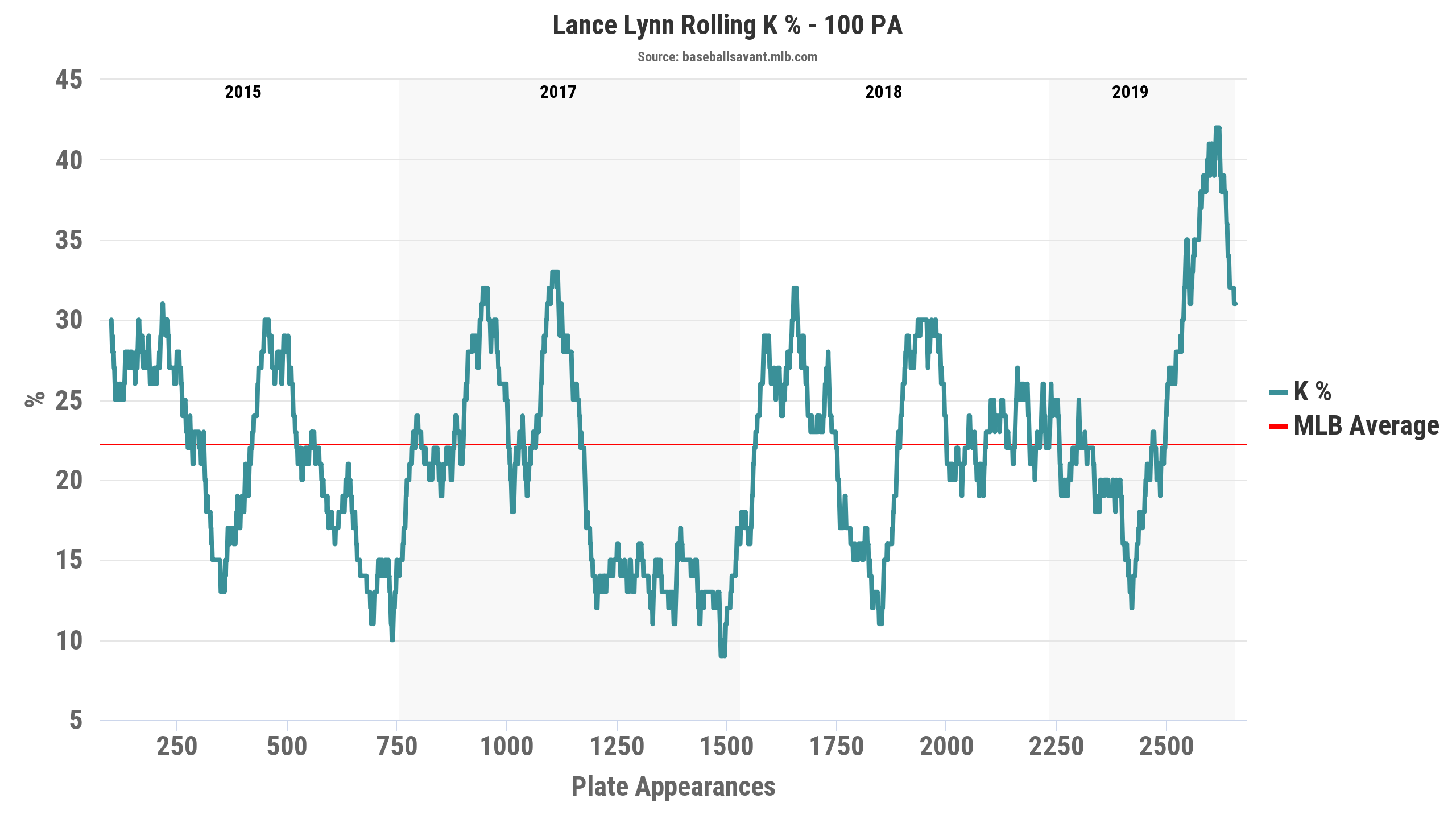

There’s a pretty clear driver behind the revitalization of Lynn. Here’s a graph showing his rolling strikeout-percentage:

Throughout the course of any given year, Lynn often fluctuates between striking hitters out and not striking hitters out. But in 2019, his strikeout rate has skyrocketed. This is a little surprising, because, for the most part, Lynn relies heavily on fastballs. More than three-quarters of his pitches are of a fastball variant—he throws a four-seam half of the time and mixes in his sinker and cutter. Every so often, he sprinkles in a curveball, and even more infrequently he has a changeup. Given his repertoire, you won’t be surprised that—while he gets a fair amount of strikeouts—Lynn also allows a lot of contact. What’s surprising is that he’s much better at limiting hard contact than you probably imagine he is.

By xwoBACON, Lynn is in the 65th percentile, so he’s actually above average on balls on contact. From the table above, we see some familiar names in his vicinity by xwoBACON: Buehler, Sale, and Scherzer (who actually is tied with Lynn). In sum, Lynn has been striking out hitters at what is essentially a Buehlerian rate while limiting hard contact like Scherzer for over a month now. Paired with a limited number of walks, he’s checked most of the boxes you can to be an elite pitcher. So how has he done it?

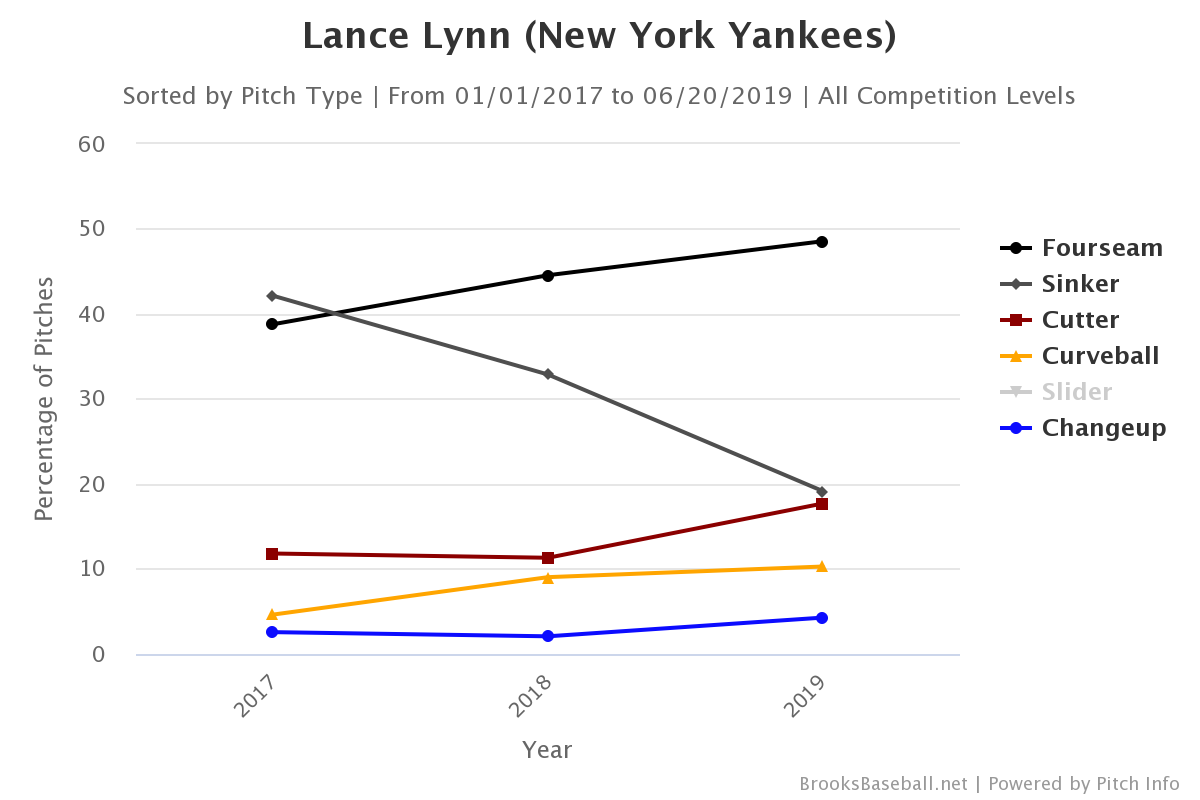

The most obvious change is Lynn is moving towards his four-seamer and cutter, which are good, and away from his sinker, which is not good.

Lynn, pitch usage:

By wOBA, Lynn has the eleventh-best cutter in baseball, and by xwOBA, it’s the eighth-best cutter in the league. His cutter xwOBA ties Martin Perez’s cutter xwOBA—no wonder Lynn has started to incorporate it. Lynn has already nearly doubled his cutter usage from last year, but Perez is evidence that, if Lynn wanted to, I suspect he could throw his cutter somewhere around a third of the time. Obviously, there comes a point of diminishing returns—Lynn’s cutter plays off of his four-seamer, so he can’t just throw a cutter. With that said, I have no doubt in my mind that he could (and should!) use it more than he is right now.

Hit Me With Your Best (Arm) Slot

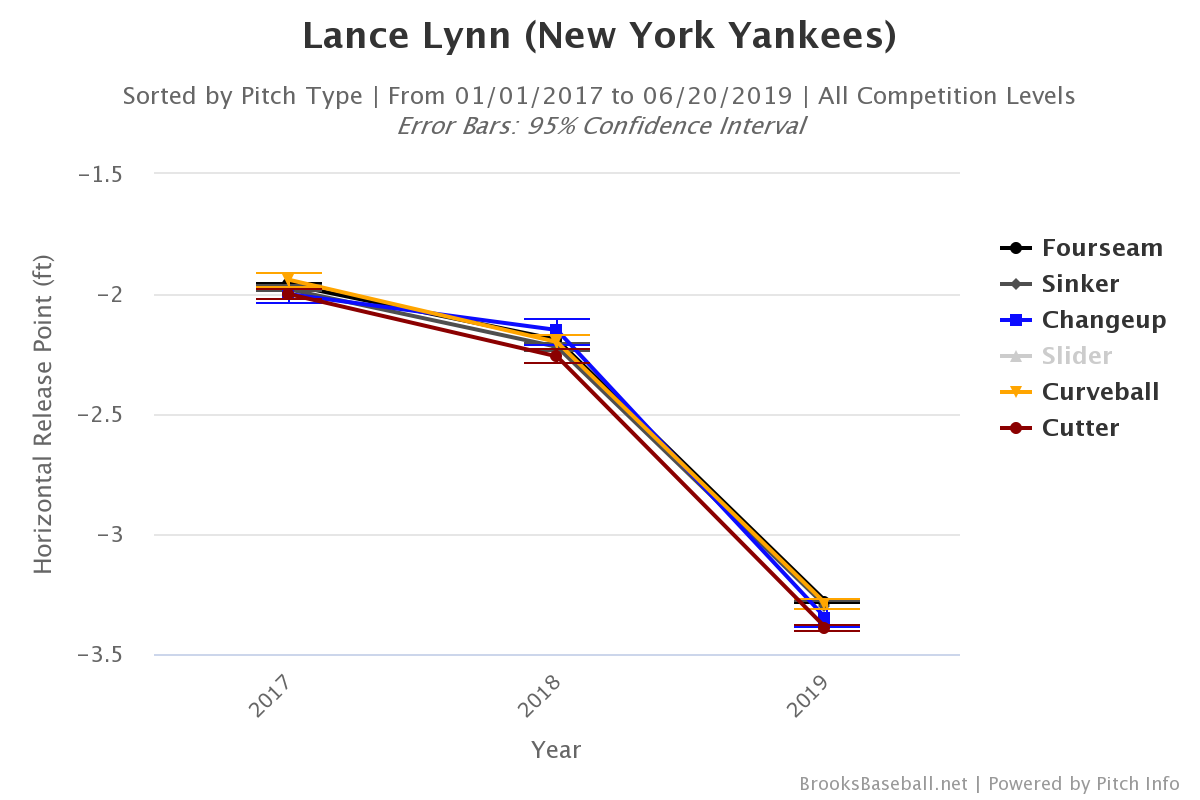

Other changes aren’t as obvious—at least to the passive observer. Lynn has dramatically changed his arm slot. Lynn’s horizontal arm slot:

We can see that this is a drastic change, but maybe this isn’t all that easy to visualize.

Lynn’s release points, 2018 versus 2019:

Lynn has shifted his release point an entire foot to his arm-side. It seems intuitive that he’s found more of a natural arm slot. From 2011 to 2017, Lynn has been progressively losing velocity. In 2018, he jumped up about 1.5 mph to a career-high in velocity, and now he’s seen another jump this year.

Often, when a pitcher changes their release point, it comes with side effects. It can change pitch velocity—we’ve seen this with, say, James Paxton—but also, it changes pitch movement. In 2018, Lynn had the eighth most horizontal movement on his cutter in the league. This year, he has the seventh least horizontal movement on his cutter. His cutter wasn’t bad before, but the 2017 and 2019 versions of his cutter with lesser horizontal movement have proven to be much superior to his 2018 cutter. His cutter is the pitch that has benefited the most from his change in arm slot, both because of change in movement and velocity differential.

Ahead Of The Curve

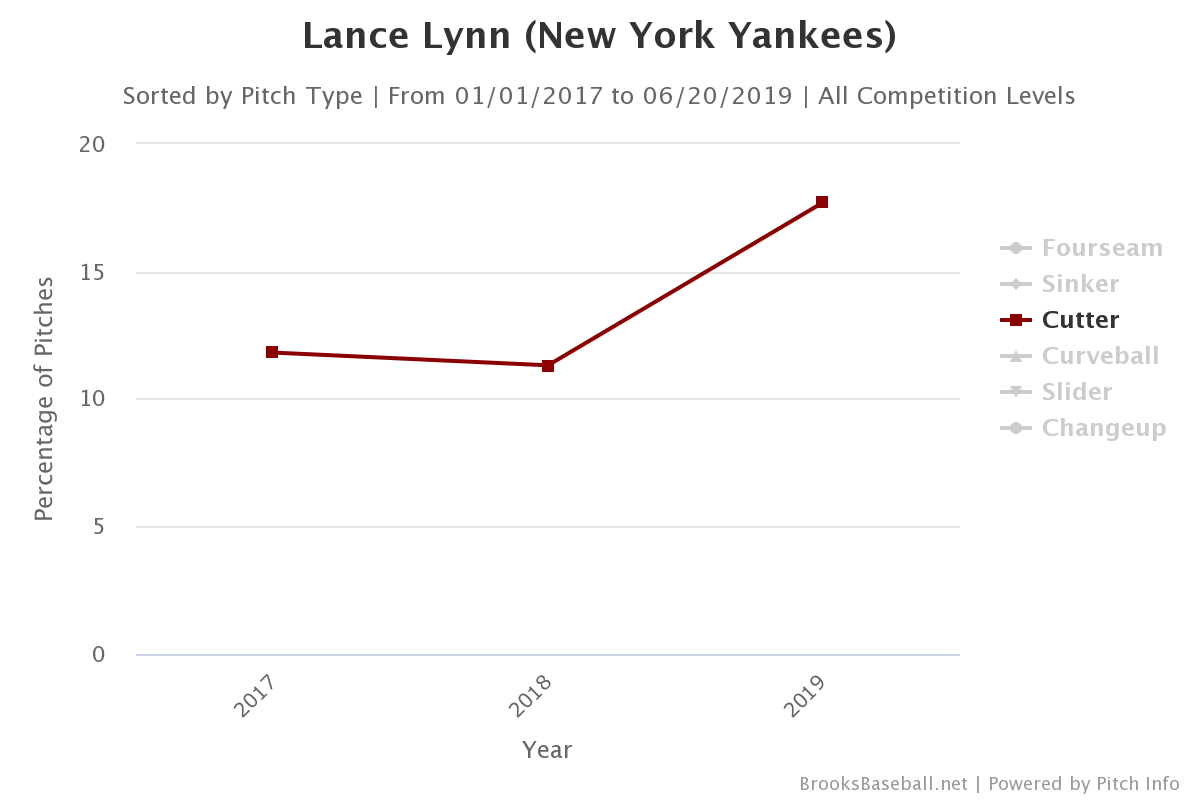

To reiterate, Lynn has done this with his cutter usage:

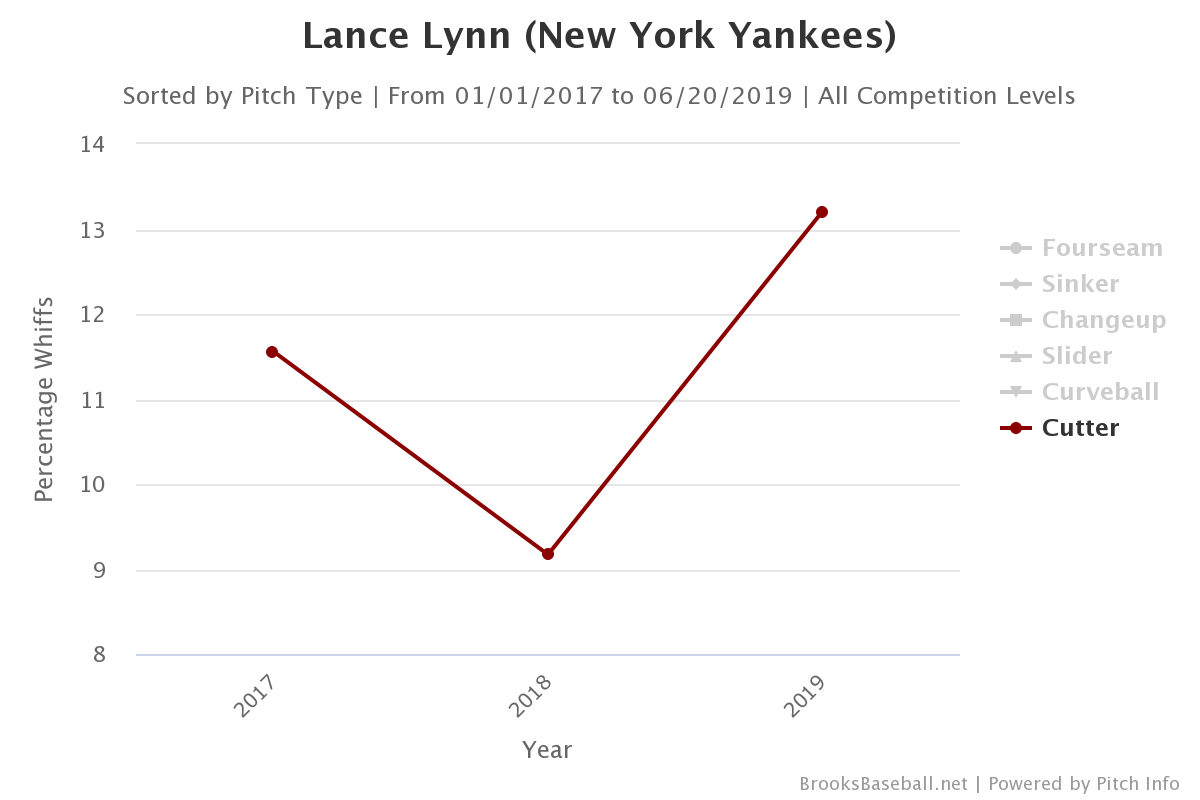

And here’s how his cutter has responded, by whiff percentage:

His cutter has gotten all of the fanfare. Most have focused on his cutter—and even I have made it a focal point thus far—but it seems his curveball has gone unnoticed. Especially in the past month.

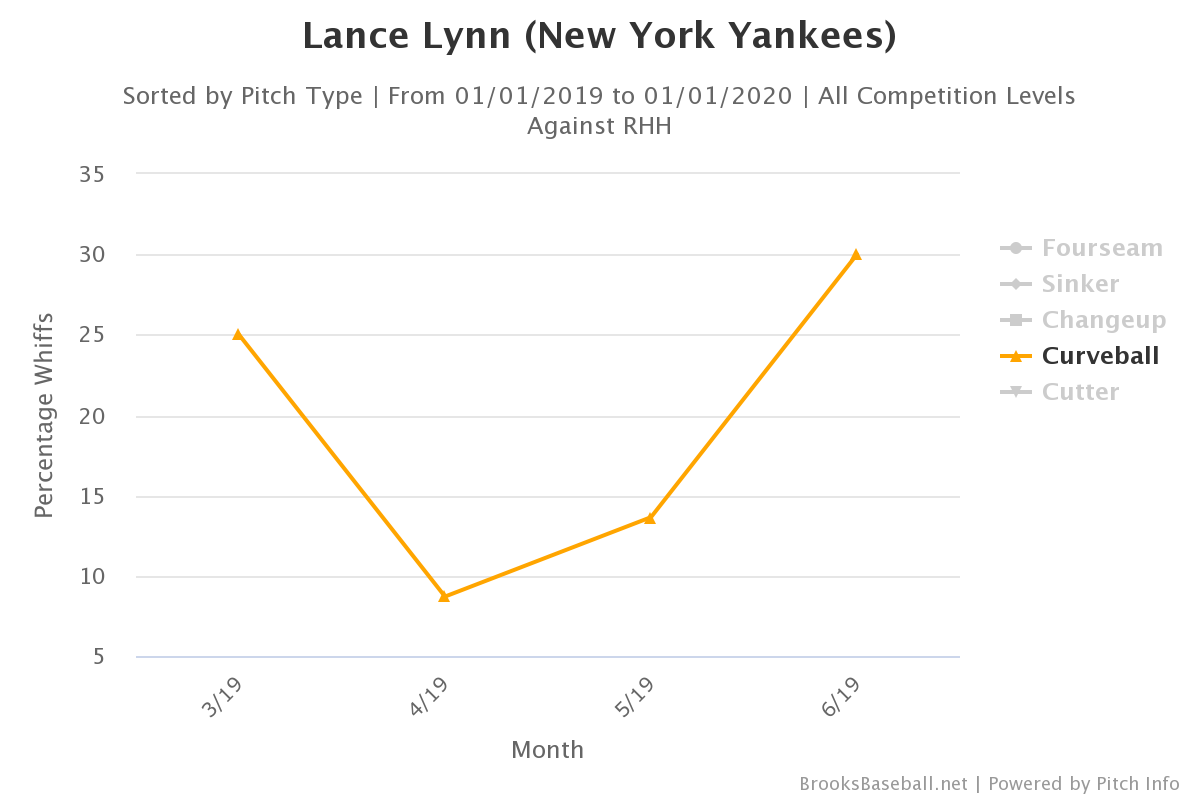

By month, his curveball’s whiff percentage in 2019:

The resurrection of his cutter is a meaningful development, especially since it deepens his repertoire, but I’m not convinced that his curveball shouldn’t be demanding a majority of the conversation. He’s only thrown 30 of them in June, but he’s made every one count. We’ll come back to this later.

The weird thing is, Lynn has thrown his four-seam fastball in the zone more than ever, but hitters are swinging at them less—his in-zone swing percentage is down on his fastball from 71.1% to 64%. That’s the lowest it’s been since 2012. Accordingly, by xwOBA, his four-seamer is the best it’s ever been. It’s fascinating, yet perplexing.

In 2017, the number of Lynn’s four-seamers that went for called strikes was 17.5%. In 2018? 17.0%. In 2019, though, that number has jumped to 20.2%. On top of this, hitters have taken far more two-strike four-seam fastballs for called strikes. In 2018, 4.1% of Lynn’s four-seam fastballs in two-strike counts were taken for a strike. In 2019, though, that number has more than doubled to 8.8%.

This raises a few obvious questions: Why are hitters taking more pitches for strike three? Why are hitters taking more if he’s throwing in the zone more? The answer, I gather, is deception. More specifically: pitch tunneling. It’s not the answer alone—it never is—but to me, it’s the biggest reason.

Pitch Tunneling

One thing we can do to look at deception is to check the differential between zone-swing percentage and outside-swing percentage. If hitters are taking pitches in the zone, and offering at pitches out of the zone, then we can deduce that the pitcher has been deceptive. We’ll experiment with Lynn.

Lynn’s overall zone-swing/outside-swing percentage differential from 2017-2019:

| O-Swing% | Z-Swing% | Z-O% | |

| 2017 | 25.3 | 65.6 | 40.3 |

| 2018 | 27.6 | 68.5 | 40.9 |

| 2019 | 26.7 | 65.9 | 39.2 |

We’re looking at an ever-so-slight improvement. His zone-swing percentage is one of the better numbers in the league, but Lynn doesn’t get hitters to chase nearly as much as he should (or could). It’s slight, but it is his lowest number (lower is better) since 2014. While these are his yearly numbers—and we know Lynn has been very different between the two time frames—this isn’t enough to draw any conclusions with any sort of certainty.

Lynn’s zone-swing/outside-swing percentage differential, from 2017 to 2019. This time, only for his cutter:

| O-Swing% | Z-Swing% | Z-O% | |

| 2017 | 26.2 | 68.9 | 42.7 |

| 2018 | 22.7 | 67.8 | 45.1 |

| 2019 | 32.7 | 62.4 | 29.7 |

On his cutter, he’s getting hitters to chase at a career-high, and getting hitters to take for a career-low. In both ways, he’s moving in the right direction, thus why his zone minus outside percentage is so robust.

We don’t have to rely on peripheral metrics to see how well Lynn is tunneling, though. Baseball Prospectus has some pitch tunneling metrics, and although they’re in their infancy, they appear to be very legitimate.

We’ll look at two: Pre-Tunnel Max, and Pre-Tunnel Max Time. You can read their words directly, but Pre-Tunnel Max tells us, at the decision point, how far apart back-to-back pitches were. Pre-Tunnel Max Time tells us when the second pitch in the pairing is at the greatest distance for the first. For Pre-Tunnel Max, a lower value is better. For Pre-Tunnel Max Time, the closer to 0.150, the better.

Here are Lynn’s tunneling numbers, from 2017 to 2019:

| Value | Percentile | |

| Pre-Tunnel Max, 2017 | 1.47 | 75 |

| Pre-Tunnel Max, 2018 | 1.43 | 86 |

| Pre-Tunnel Max, 2019 | 1.34 | 94 |

| Pre-Tunnel Max Time, 2017 | 0.163 | 94 |

| Pre-Tunnel Max Time, 2018 | 0.166 | 75 |

| Pre-Tunnel Max Time, 2019 | 0.164 | 86 |

You can see that Lynn has significantly improved his Pre-Tunnel Max from the previous two years, and although it seems like an insignificant improvement—we’re talking two milliseconds—he has also improved his Pre-Tunnel Max Time by a substantial amount since last year. It appears that, although his Pre-Tunnel Max Time was better in 2017, Pre-Tunnel Max has been a more important factor for Lynn. This seems intuitive, as an improvement of 0.13 inches in Pre-Tunnel Max seems more meaningful than a one millisecond difference in Pre-Tunnel Max Time—at least here it rings true. Regardless, Lynn has shown an increased ability to tunnel his pitches.

My hypothesis for why is simple. In 2017, Lynn had too much ride on his fastball. Even though the shape of his cutter was similar to his cutter now, the 8.9 inches of horizontal movement on his four-seamer was undermining his pitch tunnel. In 2018, he reduced the ride on his fastball—his 5.4 inches of horizontal movement are essentially unchanged today—but the shape of his cutter had too much vertical and horizontal movement. Today, his horizontal movement on his cutter is minimal, and his fastball has less ride. As I’ve mentioned, he’s added even more velocity to his fastball and cutter. As it turns out, faster pitches and better tunneling is a delicious combination.

Approach, Approach, Approach

This year, there’s been a bad Lance Lynn, and an elite Lance Lynn. The real one is probably somewhere in between, but we’ll break them up into two time frames. To save you some time, I’ll say that, while Lynn has remained equally mediocre against left-handed hitters, he’s really started to come on against right-handed hitters.

Against righties:

| IP | K-BB% | ERA | FIP | xFIP | |

| 3/31 – 5/9 | 18.2 | 8.1 | 7.23 | 4.51 | 5.41 |

| 5/10 – 6/22 | 30.1 | 43.8 | 3.26 | 2.35 | 1.61 |

The difference between the two is immense, and it all comes as a result of a better pitching approach. We’ll examine how Lynn has changed throughout the course of the year.

Here are some pitch plots of four starts from the first time frame, all against righties:

And five starts from the second time frame, again, strictly against righties:

To save you the time and annoyance of scrolling back and forth and comparing, I’ll summarize it for you.

Time frame one:

- Fastball all over the place

- Sinker over the plate

- Wasted curveballs

- Can’t decide where the cutter goes

Time frame two:

- Fastballs up, away, or up and away

- Sinkers in and off the plate, or non-existent

- Cutter down and away

- More consistent curveball location, with purpose

It’s far from perfect, and there’s quite a bit of variation between games, but there’s a lot of good stuff going on here. First and foremost, he’s locating his four-seam fastball in more favorable spots. Specifically, he’s throwing inside to hitters far less frequently. More recently, he’s started to move away from his sinker, but when he has used it, he’s kept it in on the hands of hitters. Whether it’s plan or execution, Lynn is doing a better job grouping his curveballs and cutters together. Additionally, he’s keeping them away from hitters, but in spots where they’re alluring enough to offer at. Nevertheless, everything starts with the fastball.

The numbers support the eye test, too. What is perhaps inconspicuous is Lynn is doing a better job of staying away from the middle of the plate. On all of his pitches, he has gone from 9.2% pitches located middle-middle to 6.9%. Similarly (but not the same), he has reduced his amount of pitches in the “heart” of the plate from 28.6% to 23.7%.

He’s done a better job of keeping his cutter and curveball out of the zone, too. From time frame one to two, he’s gone from 25.7% cutters out of the zone to 34.0%—this is, in part, why we’ve seen the cutter emerge as a weapon. For his curveball, he’s gone from 28.0% pitches out of the zone to 33.0%.

Levitate, Levitate, Levitate, Levitate

The thing is, I’m not convinced that Lynn can’t unlock one more aspect to his game. It’s gotten to the point where I’ve written about it so much lately, that I’ve been trying to get away from it. Alas, here I am. By fastball velocity, Lynn is middle of the road: 47th percentile. But by spin rate, he’s in the 86th percentile.

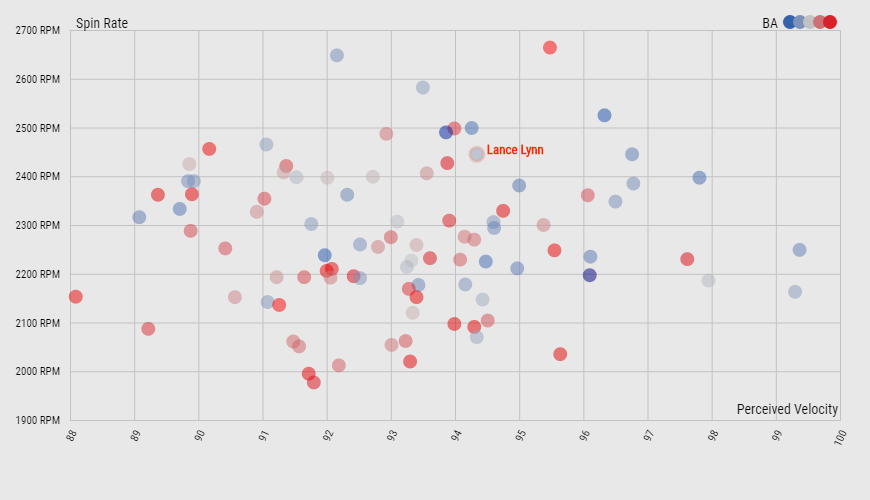

I present to you a scatter plot, plotted by perceived fastball velocity and spin rate:

As you’d have it, Lynn throws his fastball about as hard as Trevor Bauer, Justin Verlander, Lucas Giolito, and Max Scherzer. While Lynn has lower spin than Scherzer and Verlander, he gets a significant amount of spin over Giolito and Bauer. That blue dot right above Lynn? It’s Scherzer. Lynn’s fastball, as is, is quite good, but this begs the question, why isn’t it even better?

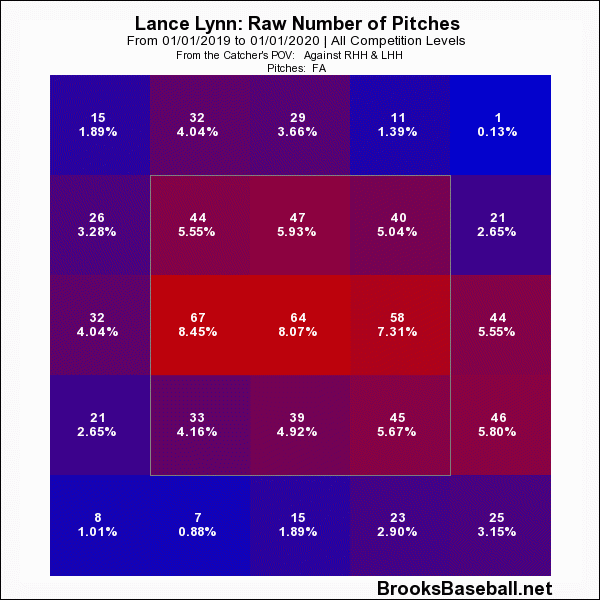

Here’s where Lynn has thrown his fastball in 2019:

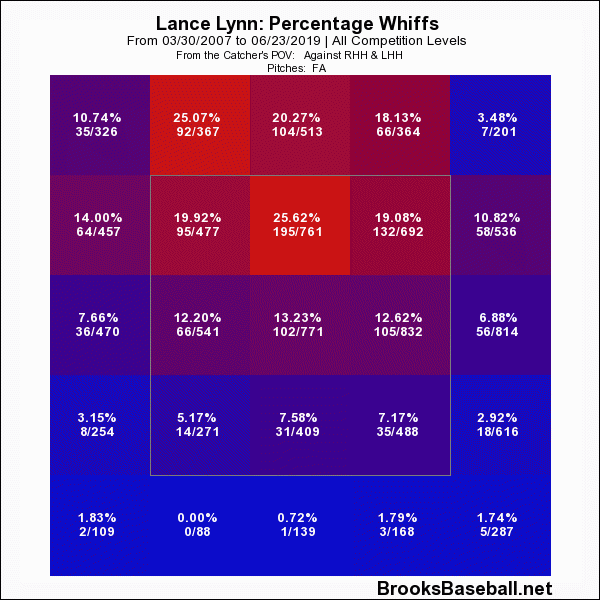

But here’s where Lynn has gotten his whiffs, over his career:

Lynn’s been throwing his fastball to the center of the plate an awful lot, but that’s not his optimal zone. When Lynn pitches to the upper-third of the zone or out of the zone: whiff city. But Lynn pitches down in the zone about as often he pitches up in the zone. It’s hard to know for certain how elevating his fastball would affect his newfound pitch tunnel, but I can only imagine it would be a lethal combination with his curveball, and probably his cutter too. Regardless of whether or not he starts to elevate his fastball—which, he’s done more of recently and I hope he continues to do—I would like to see an uptick in cutter and curveball usage.

There’s potential room for improvement, but it’s hard to argue with the results. Lance Lynn has never sniffed elite territory, but for more than a month, he’s been pitching with the best of them. His approach isn’t bulletproof, and the results aren’t wholly sustainable, but there’s no reason he shouldn’t be able to preserve some of the improvements he’s made. He’s always had the tools, but now he’s added improved pitch tunneling, velocity, and approach into the mix. He almost surely hasn’t made himself anything even vaguely resembling an ace, but he’s at least made himself more interesting. Keep an eye on that curveball.

Featured image by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

Lance Lynn has been interesting most of his career. He was great in 2017. Heck, he was even interesting for a big chunk of 2018. It is kind of odd that you don’t talk about Lynn’s TJ more – you mention the declining velocity (which coincided with a TJ) and now velocity is improving and he is changing his arm slot which also coincides with being a few years removed from TJ. Arm slots are usually about what feels most comfortable – a lack of pain and increased flexibility is going to help with that. To me, the TJ is the whole story and I talk about Lynn a lot on these digital pages! He is a fun guy to watch pitch – its fastballs and more fastballs – he changes speeds and cuts them really well. He is kind of a poor-man’s Greg Maddux in that way. Personally, I think tunneling is just superficial analysis laid over the top of what he has always done. I would argue that Lynn has been really good for long stretches before – he was among the WHIP leaders for the entire first half of 2017. I know WHIP is not the stat of the day, but I think it is good a measure as any and he has done a good job with that in the past at times. Its all part of the same story though – he is really good with his FB and that is almost entirely what he throws. Moderate improvements or declines in feel for his FB have a huge effect on the end results because it is all he does. On days where he doesn’t have command he will just try to paint regardless of count and walk 6 guys, on days where he has good feel he will induce tons of weak contact and some swings and misses. He has good feel more often than not, but it gets ugly quick when he loses it. In any case, he is older and has TJ on his resume – this could all fall apart any day but he has been a great streaming option this year. Always happy to see a positive spotlight on a veteran player.

I’m not sure I agree with the sentiment that Lynn has been interesting before. At least, not for half a decade. His xwOBA in the Statcast era has been league, and this is the first time it’s been — 20 points better than his league average!

You may have a point in that I should have mentioned his TJ, but as a 2500+ word article, I tried to omit as much as possible. I disagree that arm slots are always about what’s comfortable — James Paxton used to throw directly over the top — but I would agree that that’s often where it *should* be. That’s what I’ve said about Lynn. This is a *career high* velo we’re talking about.

Also, I’d push back on tunneling not being an important part of what he’s doing. It’s obvious (at least, to me) that his newer approach is more conducive to tunneling, and the numbers support that.