The sinker (or two-seam fastball if you’re not into the whole brevity thing) is one of the coolest pitches in baseball. Call it by either name, it’s essentially the same pitch and can be very aesthetically pleasing look to it. The most recent two-seam/sinker to dazzled me can be seen below and was ultimately the inspiration for this piece.

This is Kansas City Royals‘ Jorge Lopez striking out a spellbound Nolan Arenado. The movement is strong with this one.

A couple of years back Baseball Prospectus published an article (by Matthew Trueblood) discussing the fickle relationship it has with other pitches; we’ll herein refer to the pitch using its common abbreviations, ‘FT/SI’. Because of how the pitch can move, it’s difficult to use in tandem with others especially when you want to create deception. The pitch that seems to work best, along with being the most paired with the FT/SI, is the slider. The potential of this combo’s effectiveness will be revealed in a bit. Let’s get into how I’ve found some special examples of FT/SI and slider pairings.

I’ve spoken ad nauseam about pitch tunnels and while not a necessity of pitching success, it’s a desirable skill for pitchers especially with all the data that hitters now have at their disposal. Four-seam fastballs are easy to tunnel off of so long as its trajectory adheres to the next pitch thrown (e.g.- high location for heavier-breaking pitches). And four-seam fastballs (generally) move much less than any other pitch making them ideal to either start or complete a tunnel. Pitches with extra movement create the possibility of disjointed paths, more so if you don’t have solid control of one or more of your pitches.

The facilitation of a tunnel lies in the ability to have tight release points, as well as generating the right kind of spin under a functional spin axis which allows the pitches to create something of a symbiotic relationship. It goes without saying that velocity spreads between pitches matter a lot as well.

Since the FT/SI is expected to move much differently than a four-seam fastball while still being thrown as hard, I wanted to find out who commands this pitch the best when creating pitch tunnels given the type of movement the FT/SI generally adheres to.

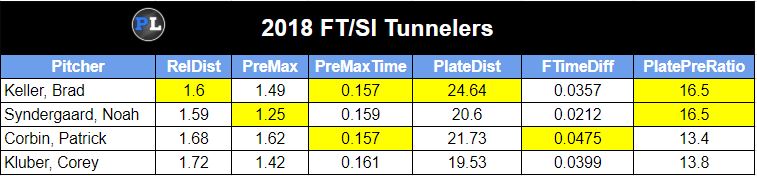

I started by looking at all the BP tunneling data using two-pitch combos featuring an FT/SI. From there, I broke off pitchers who didn’t meet a release distance (RelDist) smaller than 2 inches. The importance of release points is outlined in an earlier article I wrote. To elaborate on what release distance consists of, its a measurement based on a three-dimensional radius of the exact spot the ball was released (arm slots and extensions have the biggest effect on this).

Then I looked at the ratio of how far apart the two pitches ended up after they hit the tunnel point (about 150 ms after release) based upon the distance between the two pitches at the tunnel point (PlatePreRatio). A pitcher with a PlatePreRatio of 10 would be interpreted as having both pitches ending up 10-times further apart than they were once they hit the tunnel point. This matters because it tells us how much the pitch moved at the point the hitter’s eye has to communicate with the brain to make a determination of what is being thrown. For example, the hitter may be expecting fastball but is actually getting a slider. This causes the hitter to adjust his swing for the (incorrectly) expected location and/or velocity.

I inspected each pre-tunnel max times (PreMax) which essentially measures how long the pitches stick together before breaking off at the tunnel point. The closer to the 150 ms point, the better because that’s less time for the hitters to make up their minds about the pitch. I also considered all remaining tunneling data as a supplement for my conclusions and narrowed it down to four pitchers I felt stood out the most using the FT/SI ‘in band’ with other pitches.

Before I give my findings and explanations, limitations have to be mentioned. Just because these pitchers, on average, created the ‘best’ tunnels does not mean they are the most effective. You can create an amazing tunnel but if the locations aren’t, it’s worthless. Each pitch’s Pitch Info Pitch Value may not be ideal, either. Even that isn’t the best criteria because we don’t know how each pitcher used a certain pitch. Context is everything when dealing with data that requires information that doesn’t create mutual exclusions.

Here are four pitchers who are best set up to cause fits for the hitter with this somewhat elusive ability. Each pitcher is listed with the number of times the combo is thrown in parentheses, followed by the main tunneling data with visuals to demonstrate. Below each gif is a plot pulled from Brooks Baseball giving the 2018 average vertical and horizontal movement. The black dot in between both pitch plots marks the avearage release point.

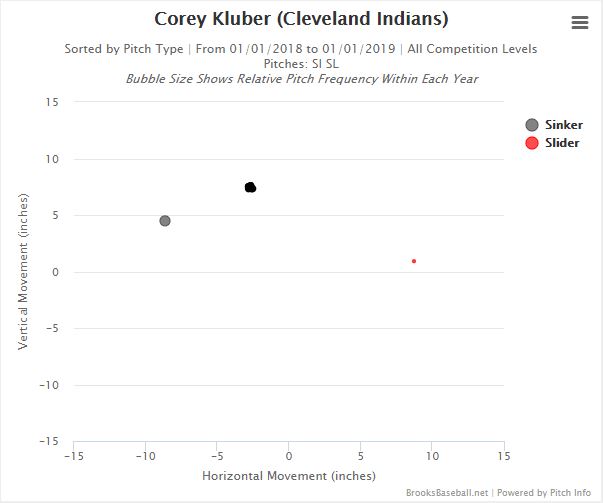

Corey Kluber– Sinker/Slider (66)

1.72″ RelDist, 13.8 PlatePreRatio, 161 ms PreMax

Kluber by far creates the most movement of any other pitcher I included. His release points aren’t quite as tight as the others (1.72″) and the two pitches broke off about 11 ms before the tunnel point. 11 ms seems minute, but it buys the hitter’s response system a little extra time. Despite that, it’s simply amazing how well the duo appears to work off each other. Kluber’s slider was one of the best in baseball (3.54 wSL/C) but his FT/SI wasn’t great (-0.85 wSI/C). Had he thrown this combination more often, perhaps he could have increased its value.

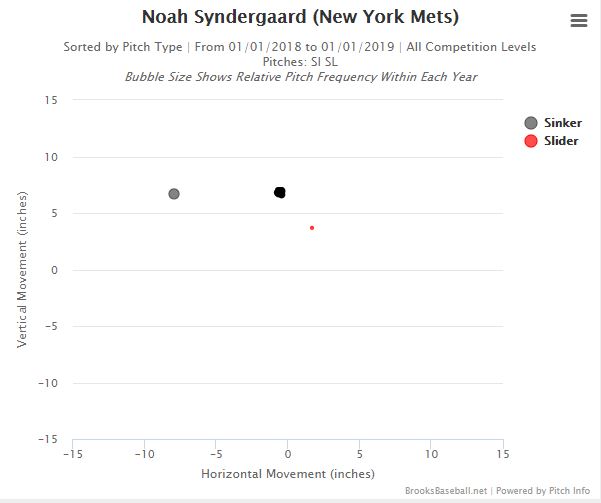

Noah Syndergaard– Sinker/Slider (109)

1.59″ RelDist, 16.5 PlatePreRatio, 159 ms PreMax

Syndergaard gets some insane FT/SI run to the right while his slider doesn’t have as much movement. Because of the FT/SI’s motion, it creates (along with Brad Keller) the biggest ratio spread (from the tunnel point) at home plate. Like Kluber, Syndergaard’s slider was one of the better versions in baseball. His FT/SI wasn’t as good but still produced somewhat positive results (0.41 wSI/C). Again, we don’t know how the latter was used, we are only concerned with the tunneling prospects.

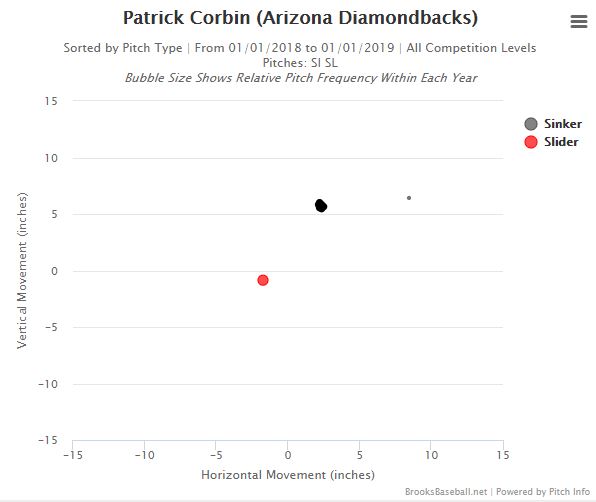

Patrick Corbin– Sinker/Slider (211)

1.68″ RelDist, 13.4 PlatePreRatio, 157 ms PreMax

Corbin loves his slider (1.35 wSL/C) and he’s one of the few (starting) pitchers who use a breaking pitch more often than a fastball. We see that Corbin produces a large spread between the two pitches, with his FT/SI breaking in to righties and the slider dropping off diagonally to the left. Corbin uses this combo more than any other pitcher who made the initial cuts. Could that have anything to do with his breakout 2018 season?

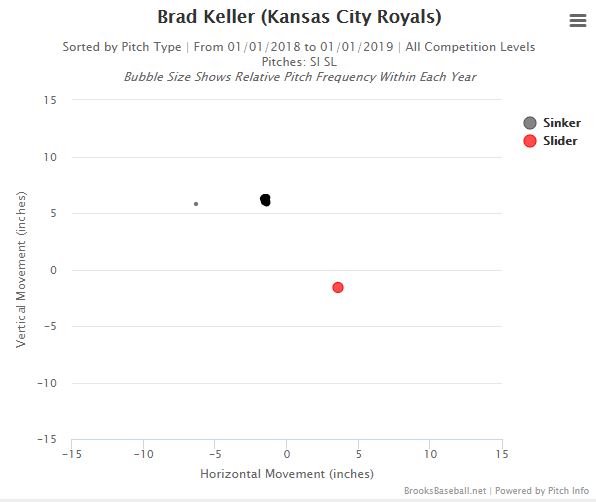

Brad Keller– Sinker/Slider (72)

1.60″ RelDis, 16.5 PlatePreRatio, 157 ms PreMax

Keller might be my favorite up and coming pitcher to watch this coming season. At times his FT/SI was dynamite (11th overall in 2018). His league average slider could be considered a slurve considering how the pitch breaks. Keller’s duo mirrors that of Corbin with quite a bit more break on the slider/slurve. Keller could be even more effective should Cam Gallagher be his batterymate on a somewhat regular basis.

Now that the elite has been presented, here is all the data I collected on each of them. Yellow boxes are the best in their respective categories.

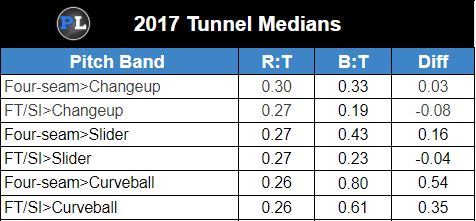

The research conducted in the referenced BP article shows that pairing the three main offspeed/breaking pitches clearly work better with the four-seam than the FT/SI. These are not averages but figures from the median pitcher in each category. R:T is Release:Tunnel is the ratio of the difference between the release point and when the pitch reaches the tunnel point. B:T or Break:Tunnel is the ratio differential from the tunnel point to the time the pitch reaches the plate.

data via Baseball Prospectus

The curveball is the pitch that seems to work best with the FT/SI. Interestingly, no pitchers using the curve with the FT/SI came close to being considered as my subjects because the tunneling data just wasn’t impressive.

To explain the above figures, we see that most pitch bands have relatively the same R:T ratio but the B:T tells a different story. Look at the example of the FT/SI and changeup. We see that there is a very small break, which is by far the smallest of all on this chart, after the pitch hits the tunnel point. It’s much more effective using a changeup with a four-seam fastball.

That being said, while working on this research I found that Kyle Hendricks to be the only pitcher that can pair them with a level of effectiveness, though he only employed it 82 times last season. See for yourself.

Notice the pitches move very similar because Hendricks’ spin rate and axis on both pitches are nearly identical despite the difference in spin direction. His FT/SI spin rate is lower than the league average and his changeup is above. Since the changeup is thrown much slower (about 17 MPH less on average), the Magnus effect is at play which created a lower trajectory for the changeup.

FT/SI use has dropped significantly in the past several years and there are various reasons for that. One is the possibility of injuries due to overuse (see: Dallas Keuchel, Zach Britton). That makes those that still rely on it interesting if only because it’s fallen out of favor. If you’ve got great movement and velocity (see: Jordan Hicks), it can be a filthy ‘money’ pitch. Being able to pair it with another pitch, so well that it makes a hitter have to wait until its nearly too late to make up his mind, you’re going to be very tough to beat.

Some can regularly/easily create tunnels, yet it doesn’t make much difference to a hitter. Others don’t tunnel as well or as often, yet can regularly beat a hitter when they pair an FT/SI with another pitch. The key is knowing how, when and where to match it.

(Photo by Stephen Hopson/Icon Sportswire)

What are your thoughts on Flahrety this year? How likely do you think it is that he’ll be a top 20 pitcher?

I don’t think a sinker and two-seamer are the same thing. Its a sinker if you get enough sinking action on it, but for Kenley Jansen is called a cutter. I’ll be the first to say that some people’s two seamer is a sinker, but some two seamers are not necessarily sinkers unless the pitch classification is oversimplified (all advanced metrics are as they attempt digitally sample and categorize analog data). For example, a submariner isn’t going to throw sinkers on the same grip as an over-the-top pitcher just due to arm slot and effective spin – at least not the same sinker a vertical arm slot would create. That seems like a major pitch categorization error. I really do think that improper binning of pitches and batted ball outcomes are a major hurdle in making quality progress forward. If we were studying better bins and problems with what we use, we would be racing ahead of analysis of bad data – I imagine this is what happens/already happened in secret behind the public data. I think a lot of the more “interesting” findings of advanced metrics are really just highlighting bad bins. The exceptional ones very well could be the ones that are being misclassified. Comparing apples to oranges is interesting for sure! More bins are better.

I wonder if simply matching the arm slot is a crude way to measure how well they maintain arm speed and the way they hold/release the ball for pitches? It could be – the more elements of the delivery that are the same, the more similarities thorough the chain of events and the easiest thing to measure is the point where the ball leaves the hand – it is likely a proxy for many things. I say this because sometimes (often) people say things like a pitcher needs to raise an arm slot or something and I am not sure that is much more productive than telling a hitter they need to increase their EV.

I don’t think Arenado was spellbound at that pitch – I think he thought it was a ball – its not like it split the plate or even was even well located. He missed the location of chase pitch down. Whether that caught a corner or not is pretty close. On paper, that pitch is might be a beaut but I don’t think it was a lot more than luck. At the belt and out over the plate to Arendao at Coors is a bad bet. That was a pissed off look back at the umpire, not admiration of the pitch lol.

I appreciate the work you are doing. I think it is rough territory and I think you do a good job with what you have to work with. The problem of bad bins and oversimplification is a problem for everyone who works with data. Its weird, because the gatekeepers hold the data and they release what they feel like. I am sure they like it this way… I would bet that if you got hired by an MLB team you might see many more bins.