(Photo by Wilfred Perez/Icon Sportswire)

Former Arizona Diamondbacks pitcher Patrick Corbin has found a new home in the National League East with the Washington Nationals. One (big) reason that Corbin was such a hot commodity this offseason was due to his jump in WAR. Prior to 2018, he topped out at 3.5 WAR in 2013 and flirted with that mark again in 2017 (3.0). A 6.3 WAR is a major increase and can either be a demand for justifiable recognition or a money-oriented motive. It’s impossible to say which, especially in a (potential) walk year, caused a player to improve so drastically. I’d like to think that most players just happen to recognize how to get better at the right time and I think that has a lot to with how Corbin became a top-flight starter in 2018.

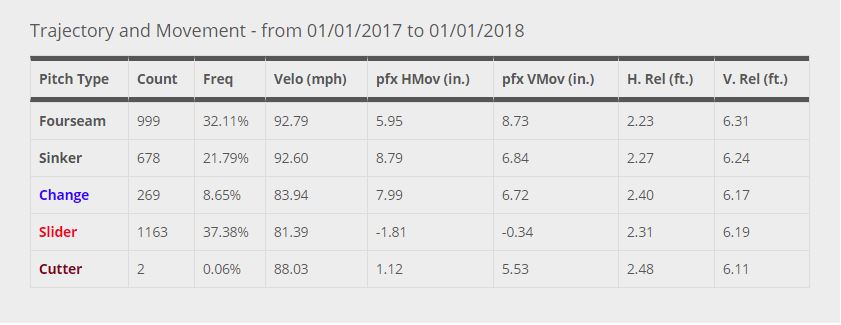

Corbin used his fastball a lot in 2017. He also had a changeup he liked to toss in, albeit at just under 10%. In 2018, that fastball usage dropped by about 5% and his changeup was almost non-existent. Corbin adjusted his repertoire to feature his slider more and introduced a curveball at a rate of 9%.

When looking at his Pitch Info Pitch Values (scaled to 100 pitches), his fastball (two and four-seam) went from a -1.13 wFB/c in 2017 to a 0.54. The last time his fastball registered positive? His 3.5 WAR 2013 season, although his fastball usage was at a much higher level (I can’t speak to that now, in the interest of my hypothesis aim). The slider also improved by over 1 point in value. Additionally his chase rate increased by about 5% and his overall contact rate dropped nearly 10%.

One mark that I found interesting was that Corbin’s hard-hit rate when up from about 31% to 41% with a 4% increase in line drives. Corbin’s velocity didn’t increase and he threw fewer fastballs. I have some ideas on this, mainly from an Effective Velocity standpoint, but I’m going to stick with my main idea in order not to convolute this theory. Keep in mind that hard contact doesn’t tell the whole story because we don’t know the context. We could surmise since his BABIP went down .020, hitters were just unlucky with batted ball events, but I digress.

Take a look below at Corbin’s trajectory and movement charts from both 2017 (Chart 1) and 2018 (Chart 2).

CHART 1

CHART 2

Corbin’s horizontal movement on his fastball dropped over 1 inch on average in 2018 with about a half inch extra movement on the fourseam. His sinker had fairly negligible change. But what makes this interesting is the slider. Its average vertical movement dropped .1 inches with the horizontal break improving by over half an inch. While the latter might not seem like a lot, under the right circumstances it can make all the difference in the world.

Notice his vertical release points for his fastballs moved up a bit with his slider matching in kind. Almost no change horizontally on his fastballs but a minor adjustment on the slider’s.

Aware that his slider now has much more vertical break, he was able to create more separation between the two pitches. That coupled with the decrease in horizontal movement, that can mean a bit more time in a tunnel for the slider. When we’re talking about fractions of a second, that has the potential to throw off a hitter just enough. From an Ev perspective, we aren’t necessarily concerned with swing and miss but morose the ability to throw a hitter’s timing off.

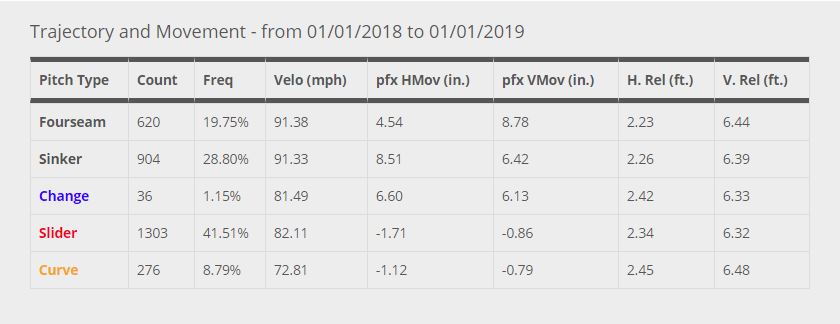

Lets take a look at this three-pitch at bat sequence from Corbin where he throws two straight fastballs and a slider for the strikeout.

This isn’t a great sequence, nor is it ideal. It works because Corbin disguises the slider well behind the fastball. Have a look at the 3D pitch chart to see how close Corbin kept the fastballs in relation to the slider (yellow).

While the release points aren’t exact (maybe a quarter-inch longer extension for the fastballs), they are good enough and the tunnels are still able to be formed.

Here is the trail overlay of the second fastball (fouled) with the slider. You’ll notice a little bit of an arch on the slider but not much serious separation from the trajectory of the two pitches. I usually like to say any trajectory difference greater than a baseball doesn’t count for an effective tunnel in my eyes. Corbin teeters on that boundary here, horizontally.

A good tunnel with decent separation just past the commit point. Same can be said for the first-pitch fastball and third pitch slider below.

The only thing to add here is you can tell Corbin made a much tighter tunnel than the previous sequence. This is just a one at-bat example of how Corbin may have been using the pitches to greater effect in 2018.

So what I feel may have happened is Corbin worked better with his slider’s spin axis. Talking trajectory on a breaking pitch, the slider moves to one side or another with vertical movement based upon its spin rate. The key factor is the aforementioned axis. You don’t want to throw the slider with the axis straight on where you want the pitch to move to. You won’t get much, if any, beneficial movement. If you release the slider with your release momentum going the same direction as your fastball, a good spin axis will create strong movement/break and can stay in a tunnel much longer. This is what I’m going to theorize happened with Corbin this year based upon his movement data via Brooks Baseball. His spin axis became more effective and he was able to generate more useful spin on his slider. Using it in tandem with his fastball made him more deceptive and a vastly improved pitcher.

If this is the case, and he can keep it up, Corbin will prove that 2018 was no anomaly.

People have varying opinions on this, but something about Corbin’s lack of zone time rubs me the wrong way. I mean, can someone really be continually effective by throwing 2/3 of his pitches outside the strike zone?

If batters start to adopt a more patient approach to Corbin I can see him struggling, especially with his unimpressive velocity.