One method that I use when evaluating a pitcher is to look at their chase rate (O-Swing%), lack of contact in the zone (Z-Contact%), and overall whiff rate. Of course, there are other ways that don’t preclude hurlers who ‘pitch to contact’ but a lot of fans love to watch a hitter look foolish and bellow on about it (“What was he swinging at there?!?). Truth is, the hitter appears foolish because the pitcher did so well practicing the art of deception (tunnels, hiding the pitch, etc). When perusing the charts on Fangraphs, I came across a pitcher who rose to prominence in 2018 who you may not have realized how efficient he really was. It will be worth keeping an eye on him both in the ‘fantasy’ as well as the ‘real’ (which I’ll be focusing on) world of baseball.

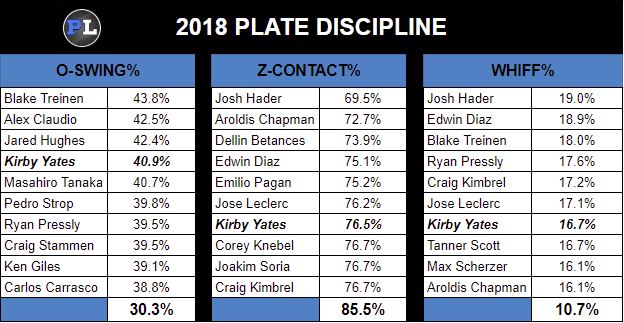

Take a look below at the chart from last season. The criteria for this list was set to a minimum of 50 innings pitched in 2018. There are a couple of pitchers, some prominent, who appear twice, but none of which reach all three sections—except for one. That pitcher would be current San Diego Padres closer, Kirby Yates. Although the Padres aren’t considered one of baseball’s best organizations, being a Major League Baseball closer takes a certain level of skill of which Yates clearly possesses.

Chart 1: Top-10 plate discipline metrics from 2018.

I do need to point out that there is a bit of caution which needs to be exercised. Notice Milwaukee Brewers relief pitcher Josh Hader tops both the zone contact and whiff rate sections. However, he doesn’t show up in the chase rate category. Could that be due to the fact that either he doesn’t throw out of the zone as much, or when he misses, he misses badly? In this case, neither is true but that consideration for others is important because I’m not about to argue that Yates is a better pitcher than Hader (all things considered). Yates might possess a sharper sword, but Hader seems to know how to wield his better.

Yates made a big change in 2018. He added a split-finger, got rid of his decent changeup, and cut way down on his slider usage. His split-finger was rated third overall in effectiveness according to Pitch Info Pitch Value and rated a 4.30 in Quality of Pitch Average (4.13 is league average). Is that weapon change how Yates was able to more than double his WAR from 2017? Or maybe it is why his WHIP dropped below 1.00, his K/BB took a minor jump, and his SIERA dropped more than 0.2 points to 2.26?

Let’s take on the above chart metrics one at a time. First, we’ll start with O-Swing% or ‘chase rate’. It’s hard to hit a pitch (well) when it is out of the zone (.151 BAA high OOZ, .90 BAA low OOZ). It’s an even bigger challenge when a pitch appears to be heading for the zone and then suddenly drops out of it: a ‘Freeze Pitch’ if you will. Typically, breaking pitches work best that way and are just as effective using them in reverse (from outside of to inside of the zone). Yet, I’m certainly not implying that a pitcher should make a regular habit of throwing out of the zone. If you can get a hitter to chase your pitches at a high level, you’re way ahead of the game when it comes to the other intangibles. This can be accomplished by effective pitch sequencing, knowing how to spin your pitches on a useful axis to hit your locations, and of course command.

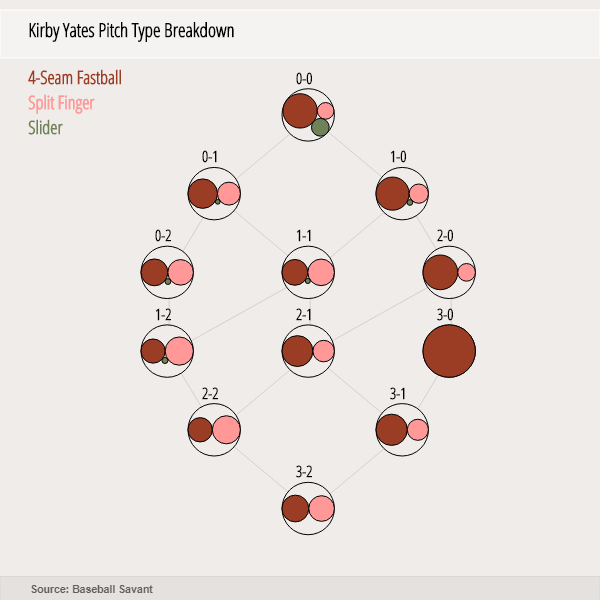

For Yates, 2018 was all about his splitter. See for yourself.

Having drawn whiffs on 43% of swings, the pitch is a big reason why his chase rate was so elevated in 2018. Overall, when looking at what ends up out of the zone for Yates, it’s a pretty even split between his four-seam and split-finger.

OK, so what is he doing so well in the zone? Let’s look into his four-seam fastball, which was good last season but not overwhelming. Its velocity was near league average (94.5 MPH), had an average exit velocity of 90.4 MPH (89.2 MPH is league average), and generated about a 25% whiff rate in 2018. Yates does throw his splitter in the zone, but not nearly as much as his fastball (a bit over a 2:1 ratio). When Yates hangs the splitter in the zone, nothing good comes of it, but has fair results when he keeps it low

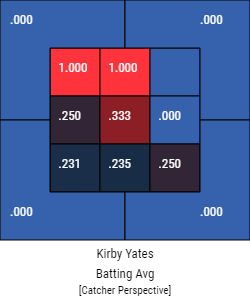

Chart 2: Batting average on splitters in the zone.

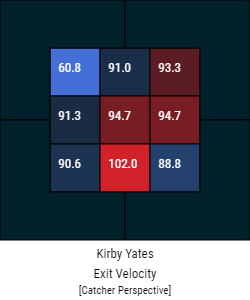

It’s not a shock to realize that trouble occurs when a pitch that’s meant to break (vertically) gets hung. Yates keeps his fastball in the zone more than his splitter (as you do) and hitters produce just a .187 batting average. Yet when hitters make contact with the fastball, Chart 3 shows it’s being walloped with exceptions in zones one and nine.

Chart 3: Exit velocity on four-seam fastballs in the zone.

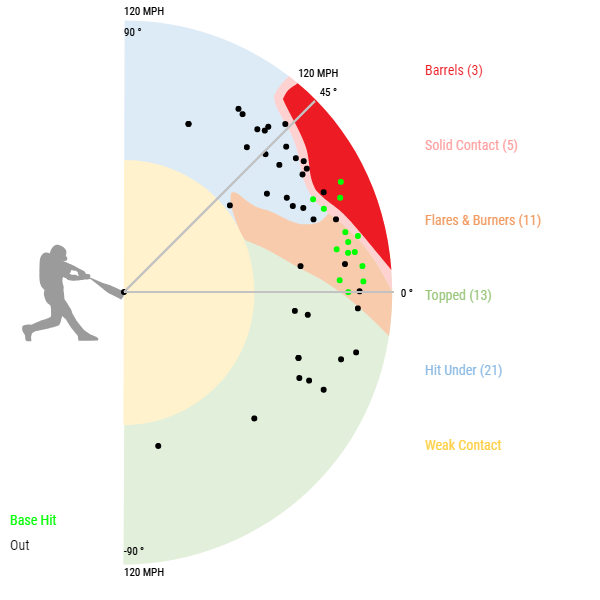

So how did he get around that? How was he able to generate a 25% whiff rate on a pitch that seems to be hit so hard? Well, let’s evaluate the circumstance. It goes without saying that just because a pitch is hit hard, it doesn’t always follow that it’s a failure of a pitch, but you should probably be careful with how and when you use it. This happens to be the case with Yates, judging by his 2018 contact type chart below, which shows that roughly 34% of contact would be considered ‘effective’ or that the pitches have a higher potential to go for base hits (estimated with Baseball Savant’s Hit Probability Breakdown tool).

Chart 4: Contact type against Yates’ fastball.

And despite some ugliness in the aforementioned metrics, Yates was accomplished in distorting hitter’s timing, which then created a fair amount of undesirable contact. His pitch selection shown in Chart 5, along with the average velocity spread between his four-seam and splitter being about 8 MPH, demonstrates his ability to keep hitters off-balance.

Chart 5: Yates’s pitch type by count.

Here’s a good example of the way Yates attacks hitters. Here he only needs three pitches to dispose of Houston Astros star shortstop Carlos Correa.

You can see really good liquidity in his pitch choice until Yates fell behind the hitter (which isn’t very often). You can assess that hitters generally have a 50/50 shot of guessing the right pitch. Those are really, really good odds, right? Of course. But…

Notice how Colorado Rockies hitter Trevor Story timed his swing. First, he was late on the four-seam fastball and fouled it off. Because the next pitch, the splitter, which was thrown at the same release point and stayed in the tunnel right up until the commit point, he was likely fooled into thinking it was another four-seam fastball and wasn’t close. Is this situation typical of Yates? Somewhat, and when he did pull it off, he was able to dismantle the hitter.

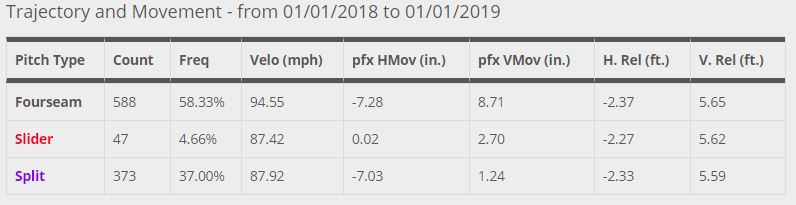

That leads me to my final points with Yates. Take a look at his release point metrics in Chart 6 (H. Rel and V. Rel) as well as his movement in chart Chart 7.

Chart 6: Yates’s pitch trajectory and movement.

You see both average release points vary by only several hundredths of an inch. That’s a huge advantage for a pitcher. The farther away each pitch is at the release point, the better equipped a hitter is to judge what is coming. That makes for a solid blueprint to tunneling success.

Chart 7: Yates’s movement by pitch type.

His movement on both the splitter and four-seam is basically built to tunnel off of each other. Even the slider would work in conjunction if he used it more. Yates’s (vertical) movement differential between the four-seam and splitter is pretty much the same as top-tier guys of splitter-happy pitchers. So it’s not an anomaly, but a distinct advantage to exploit nonetheless.

I’m not about to crown Yates a top-tier closer just yet. He’ll have to at least duplicate what he did in 2018 before he can be in that discussion. In the fantasy baseball spectrum, due to the fact that he pitched for the Padres, he flew under the radar a bit. Regardless, he’s got great stuff and the tools to become even better if he can build upon the momentum he created in 2018. Should the Padres falter late spring 2019, I wouldn’t be surprised if Yates is the most-coveted reliever as the trade deadline draws near.

(Photo by Bob Kupbens/Icon Sportswire)

Great article. It effectively explained how Yates seemingly became so good “overnight” — actually over about two years. It’s unusual to see a pitcher his age add a new pitch and make some other adjustments and go from being a guy with great strikeout rates but ugly ERAs into perhaps the game’s best closer.