Players who break out in the final month or two of the season often are not quite as accepted as legitimate as guys who have their strongest stretches early on in the season. Part of it is likely that by the final quarter or so of the season, some owners have checked out. Another possibility is just that by the home stretch, many owners often have already started to mentally label and categorize players’ stat lines into buckets. They use assessments which, once assigned, are harder to change drastically because of the biases that develop.

Take Jose Ramirez’s 2018 season for example, he was abysmal over his final 63 games, following up a .302/.401/.628 first half with a paltry .218/.366/.427. Many smart people already had either stopped following his numbers as closely, or already mentally determined he was a stud all year because of how phenomenal he was in the first half, and the result was Ramirez being a consensus top 5 pick in most fantasy leagues coming into this year. His extended struggles were hidden/downplayed, since his final stat line from 2018 still looked phenomenal.

On the other end of the spectrum, Luis Castillo’s 2018 final numbers pointed to a pitcher who was a disappointment. A 4.30 ERA and 1.22 WHIP to accompany a 10-12 record masked how much he had improved and broken out in sustainable ways down the stretch. After pitching to a 5.49 ERA with a 1.38 WHIP in his first 20 starts, he dominated to the tune of a 2.44 ERA and 0.97 WHIP in his final 11 turns. He was striking out a higher percentage of batters, and if fantasy managers paid attention to his growth, they likely reaped the rewards in 2019, as he has been one of the best starting pitchers all season.

While Ramirez and Castillo are examples who support my point, there are certainly situations where players drastically change over the final stretch and it is not more predictive. The primary point is simply that fewer fantasy players are critically analyzing stat lines near the end, for better or for worse, and that when looking at some of the biggest swings in performance for 2019, one player has shown up a lot as somebody that has given notice he may be useful for 2020 is the Milwaukee Brewers’ Adrian Houser.

What Makes Houser Interesting?

When it comes to Houser, he’s already a prime candidate to not be covered significantly. While it’s true he was a 2nd round pick back in the 2011 draft, he’s already 26. Houser debuted very shortly and had only 2 IP way back in 2015, before 13.2 IP in 2018 and had been used exclusively as a reliever. He came into 2019 as a mid-level bullpen arm, and behind young Brewers’ trendy starters like Freddy Peralta, Corbin Burnes, and Brandon Woodruff, there wasn’t any buzz for him.

Houser certainly didn’t do himself any favors to create that buzz early on either. His only appearance in April was as a starter, and he allowed a whopping 10 baserunners and five earned runs over four innings while throwing 78 pitches. From then until the end of June, he was used primarily as a multi-inning reliever, and began to hit his stride. The Brewers decided to give him another chance to build his pitch count up and to work as a starter, and he had mixed results bouncing between the rotation and bullpen. However starting from July 30th on, he has been exclusively deployed a starter. Over the eight starts he’s made, he’s become very intriguing, finishing five or more innings in six of eight appearances, and throwing 89 pitches or more on five occasions after only doing so once previously.

Impressively, he’s allowed exactly one earned run in all but two of those eight starts, with the only exceptions being four earned runs and three earned runs once each. He’s struck out more than a batter per inning over the stretch, and holds a strong 45/12 K/BB ratio in those eight starts. One start specifically worth remembering is his quality start against the Texas Rangers on 8/10, where he struck out 10.

Here’s Nomar Mazara with no chance to get to this ball breaking down and hard in on him:

https://gfycat.com/delectableremarkablegangesdolphin

Even more impressively from that same game, look at how far above the zone he gets Willie Calhoun to expand in an attempt to catch this 95 mph bullet. His ability to reach back for it to end the 5th inning with runners on base and having already thrown over 70 pitches makes it hard not to be excited:

https://gfycat.com/courteousdishonestharvestmen

The decision to let Houser face the heart of the Rangers’ lineup for a third time, as well as his success in stifling them, are very good signs for him moving forward. Here is his final pitch of the night, coming in at 95 mph again to Mazara for Houser’s 10th strikeout on pitch 96:

https://gfycat.com/understatedjaggedgalapagospenguin

Staying Grounded

Houser is an interesting pitcher in another way that stands out from the majority of his peers. In a league with increasingly more and more emphasis placed on lifting the ball in the air, and taking advantage of the juiced ball for more extra-base hits, Houser generates balls on the ground twice as often as he allows balls in the air. The result is that he is less prone to gopher balls, as his 53.8 GB% dwarfs his 24.6 FB% and 21.5 LD%. His 18.8% HR/FB rate is unspectacular, and allows him to get away with some higher numbers for base runners allowed on singles, since he isn’t allowing them to score as often.

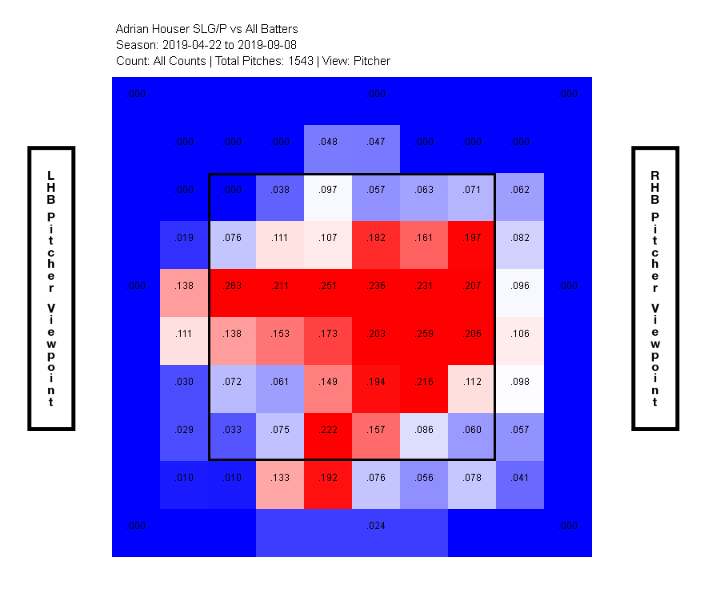

It’s not a revolutionary discovery that pitching up and out of the strike zone, or pitching well below it will be hard for batters to do damage on, but this heat map of the slugging percentage against Houser on pitches makes it pretty clear that he specifically has been successful getting batters out when they expand the zone or go after his offerings in the top of it:

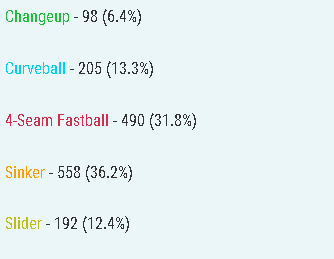

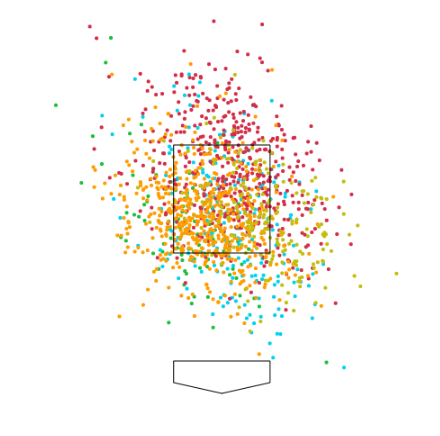

While that image is helpful for seeing where the most damage against Houser has been done, this next one from Baseball Savant is extremely helpful for seeing in more detail what Houser’s plan of attack has been in 2019. He frequently throws his 4-seam fastball high and above the zone, while pounding batters with the sinker in the bottom half of the zone and below before considering attempting to finish them off with secondary pitches if they get to two strikes. It makes sense, given his high amount of contact allowed on the ground in relation to contact allowed in the air, but the graphic does an excellent job showing just how much more often batters are seeing sinking fastballs in the zone compared to every other pitch.

Houser’s sinker has been in the strike zone on 57% of the times he has thrown it, which is notably different from the percentage in the zone of his other pitches he has thrown. Meanwhile, his 4-seam fastball is only in the zone 43% of the time while his slider, curveball, and changeup percentages in the zone are 46%, 44%, and 42% respectively. Houser has widely made an effort to either make hitters chase pitches that are not strikes, or if he ends up needing to throw a strike, then they are likely to hit his sinker on the ground.

In tandem with his ability to limiting fly balls, Houser has a knack for suppressing barreled balls. Among pitchers who have allowed 250+ batted balls in 2019, he has been 7th best at preventing a “barrel”, meaning a ball that is struck with an expected minimum batting average of .500 and 1.500 expected slugging percentage. Houser’s statcast numbers on Baseball Savant support him as a good pitcher as well. Among pitchers with 350+ batters faced in 2019, Houser’s xwOBA of .286 is in the top 25 arms, as his ranking of 22nd is sandwiched by the Dodgers’ Hyun-Jin Ryu and fellow Brewer Brandon Woodruff. With an actual wOBA of .313, it would appear that Houser has been a touch unlucky.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Add all of it together, and the profile for Houser is pretty appealing. Striking out more than a batter per inning, suppressing walks and barrels, and drawing ground balls twice as often as fly balls will play. Skeptics can point to his splits as a starter being worse thus far than as a reliever, but for a pitcher just this year being stretched out and learning the role, it feels forgivable that there have been some growing pains. Another concern is the fact that only one pitch in his arsenal is being thrown for a strike more than 46% of the time, since it may limit his ability to pitch deep into games when batters see the ball well and take him into deep counts waiting for him to give them one in the zone. Improving the percentage of strikes thrown is something conscious that Houser can improve on, and if he is ever going to be efficient in hopes of pitching deeper into starts, he will need to do so to complete his transformation from reliever to starter.

Ultimately Houser is unlikely to be an ace, but his second half is noteworthy and he has made real improvements and gains. If he makes a few more starts in September while maintaining or improving on his level of performance, Houser is definitely somebody that will be on my radar heading into 2020 if it appears in the Spring that he will be given a rotation spot, and I will be taking a flyer on at the back of my rotations once the top 50 or so are off the board.

(Photo by Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire)