Photo by Brian Rothmuller/Icon Sportswire

Ah, November. It’s the thick of the football season, hockey and basketball are back, and the midterm elections have captured the attention of most Americans. As for me, I’ve embarrassingly spent the last few weeks ignoring all of that and focusing on fantasy baseball even though the season is long over. In fairness, I need to preoccupy myself and all the other fantasy baseball-starved people until draft season begins.

So here I find myself writing about Alex Wood.

What got me going on Wood was seeing him go 195th in our mock draft to Scott Chu. As I took Mychal Givens four picks later, I thought to myself: wow, I wish I were picking Alex Wood instead of this boring guy right now. Fortunately, it was just a mock draft, and all such mistakes are forgiven. But Scott’s pick got me thinking. Why is Wood going so late in drafts? One could easily see the value in this pick, as Wood’s 2018 stats left something to be desired (3.68 ERA, 1.21 WHIP, 14.9 K-BB%, 9 wins), but if he were just his 2017 self, he could be a huge steal this late in the draft.

Indeed, in 2017 Wood was arguably an ace, pitching to a 2.72 ERA, 1.06 WHIP, 18.4 K-BB%, and 16 wins. What happened to him in 2018? Part of it is that in 2017 he probably overperformed, as his 3.32 FIP, 3.57 SIERA, .267 BABIP, and 80.1 LOB% all suggest. But could he still be a 3.40 ERA guy pitching on a great team and an excellent value late in drafts?

Wood only pitched one more inning in 2017 than he did in 2018, lending to easy comparisons. He has three pitches:

- A sinker that he throws low- and middle-away for first pitch strikes or, occasionally, to climb the ladder for a put-out.

- A changeup that he throws low-and-away to righties or down-and-in to lefties.

- His money pitch, a knuckle-curveball that he effectively backfoots to righties and throws low-and-away to lefties, with a pristine 47.8 O-Swing%, 42.3 Zone%, and 17.8 SwStr%.

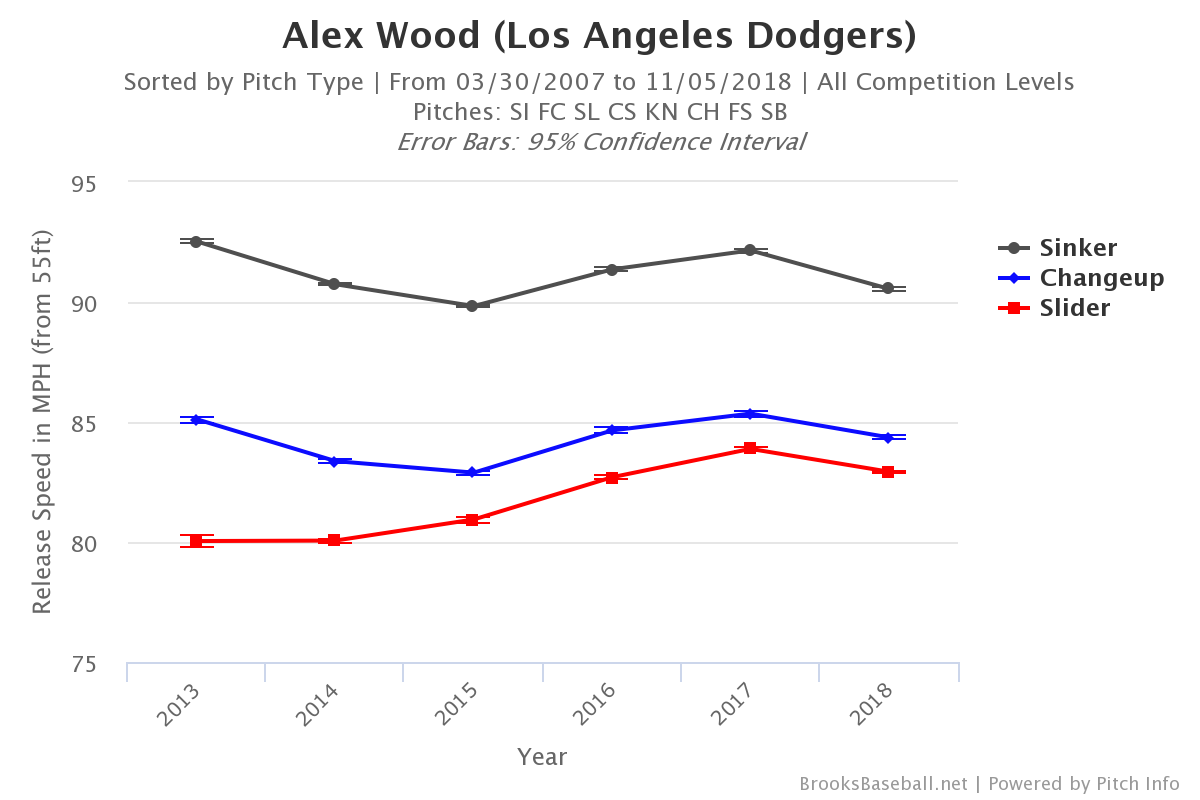

With that background, let’s dive right in. Part of what explains the dropoff in 2018 is that Wood experienced a dip in velocity across the board:

Brooks Baseball and Fangraphs at times incorrectly label the knuckle-curve as a slider, as in this case.

He lost over a tick on each of his three pitches. Unfortunately for Wood, this negatively impacted all three of them.

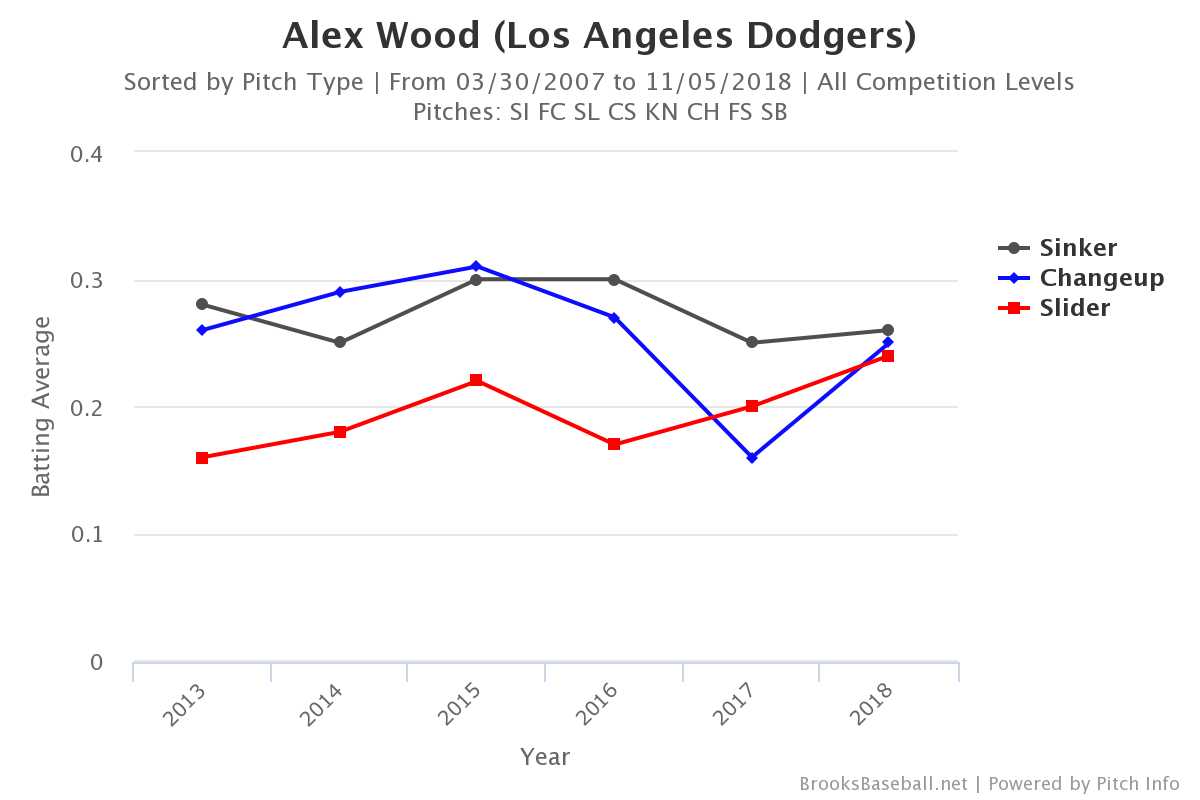

While all three pitches still retained positive pVALs in 2018, they fell dramatically from 2017 levels.

| pVAL | Sinker | Changeup | Knuckle-curve |

| 2017 | 7.0 | 16.2 | 5.0 |

| 2018 | 5.6 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

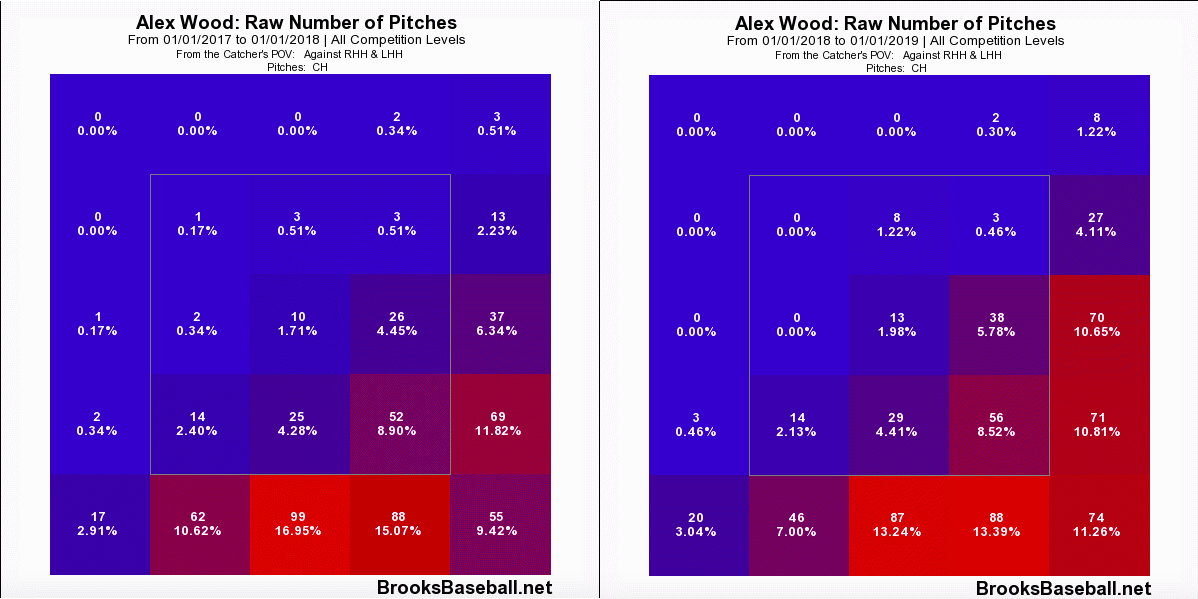

Oddly, like Scarlet, his changeup took a tumble, losing 12.3 pVAL in just one season. While the slight velocity dip wouldn’t completely explain a drop in its effectiveness (a changeup is an offspeed pitch after all), it may be that, as batters could better contend with his sinker, they were fooled less by his changeup, which is evidenced by the 8.6 point drop in O-Swing% on the pitch. Additionally, he struggled to get it down in 2018 (pictured right) as much as he did in 2017 (left).

In combination with a declining fastball, missing up with the change rendered it more hittable. In fact, Wood managed just an 11.4 SwStr% on it, a 4.7 point drop from 2017, and its batting average against went up 79 points.

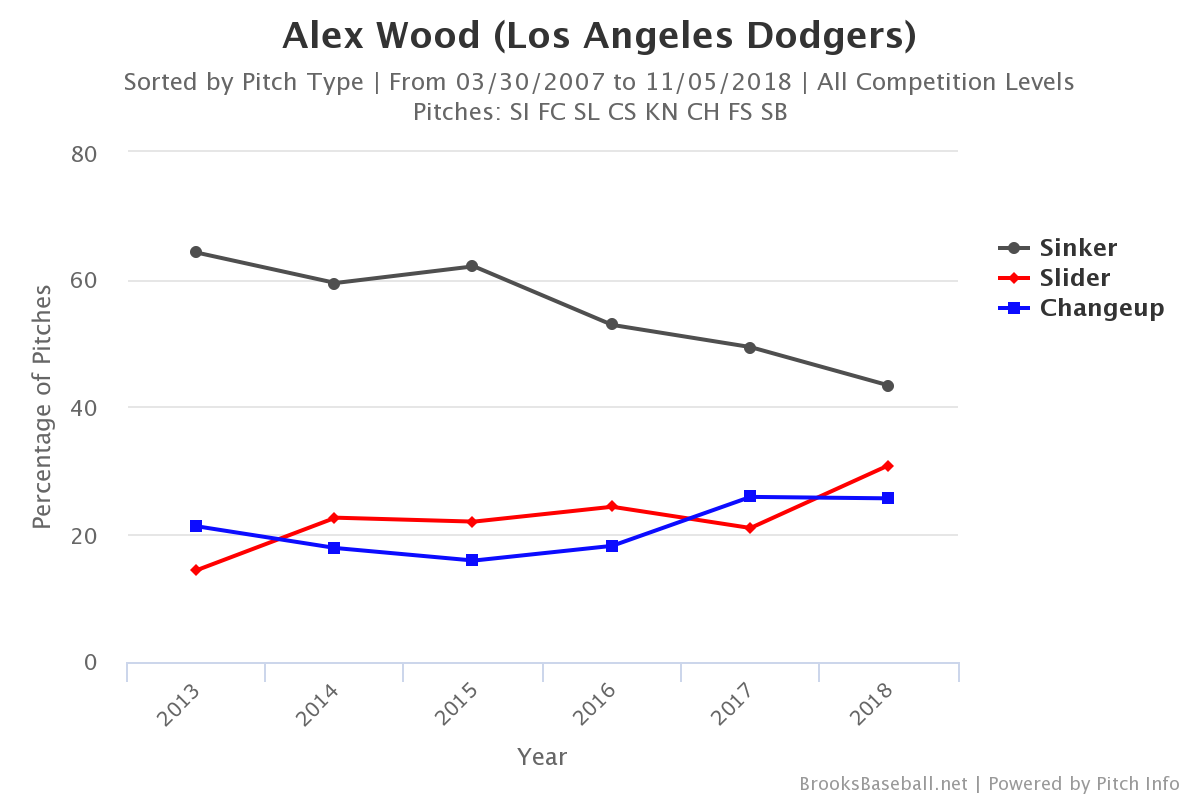

With the sinker losing velocity and the changeup becoming less effective, Wood decided to mix it up in 2018.

And there’s his change in approach! Wood’s going to his knuckle-curve (incorrectly labeled as a slider) far more often than ever before at the expense of his change and sinker. Wood is “McCullersing,” or “Corbining,” or whatever you want to call the fact that he’s beginning to turn his knuckle-curve into his primary pitch. But, you say, look at the graph dummy, Wood still throws the sinker more than the slider! Well sure, but as the season progressed, this change in repertoire became increasingly pronounced.

| Sinker% | Changeup% | Knuckle-curve% | |

| 2017 | 50.4 | 25.4 | 24.1 |

| 2018 – First Half* | 44.2 | 27.9 | 28.0 |

| 2018 – Second Half* | 41.8 | 24.8 | 33.3 |

| 2018 – August and September | 39.4 | 23.2 | 37.4 |

*I divided Wood’s season at his June 22 start because that is the halfway mark for his innings total.

Additionally, while Wood continued to open at-bats with the sinker, his two-strike approach completely changed. He climbed the ladder far less often, instead primarily relying on his knuckle-curve to backfoot righties. In 2017, with two strikes, Wood threw 261 sinkers, 192 changeups, and 186 knuckle-curves. In 2018, he threw 262 sinkers, 203 changeups, and 324 knuckle-curves.

I get why he’s doing it. That knuckle-curve truly can be excellent. Here’s an example of the way he fools righties, as it disappears to make a Hall of Fame candidate look downright silly.

[gfycat data_id=”LividAlertAfricancivet”]

However, this approach still concerns me. The groundball rate on Wood’s knuckle-curve went down 16.9 points in 2018, which accounted for the fact that his overall groundball rate dropped to 48.9%, the lowest such mark for Wood since 2014. Combined with the fact that the knuckle-curve lost velocity (which depresses groundball rate), it also lost some vertical drop. And yet he’s relying on it more than ever before.

While I understand that the knuckle-curve was an effective pitch, I’m not sure that converting his best out pitch into his primary pitch is the solution to the dip in velocity across his arsenal and the resulting ineffectiveness of his sinker and changeup.

My concerns are borne out in the numbers, too. In the second half of 2018 (as I defined above), Wood utilized the knuckle-curve significantly more and managed a 3.18 ERA with a higher groundball rate of 51.6%. Nevertheless, that ERA was belied by his WHIP ballooning to 1.23 and his FIP and SIERA increasing to 3.68 and 4.04, respectively. Further, his SwStr% dropped to 10.2% (from 11.7% in 2017), his K-BB% fell from its excellent 2017 mark to a pedestrian 12.9%, and his hard contact rate increased to 37.6% while his soft contact rate declined to 16.4%. In particular, his walk rate spiked to 7.7%, which is not exactly surprising considering the knuckle-curve is at its best below the zone. He basically became a less exciting groundball pitcher with mediocre ratios and low strikeout upside.

Based on the usage rates, Wood’s close to making the knuckle-curve his primary pitch in 2019. As explained above, I get why he’s going away from the changeup and it’s obvious why he’s throwing his sinker less: it managed a low 5.0 SwStr% and its groundball rate fell to 41.2%. Just leaning on the knuckle-curve clearly isn’t enough, however, given the drop in his overall numbers in the second half of the season. I’d like to see him embrace a new pitch instead.

Ideally, he would command a four-seam fastball like fellow lefties James Paxton and Blake Snell. As it stands, almost everything Wood throws is down in the zone, but with a four-seamer, he’d have something to throw up in the zone that he could use both as a strike pitch and a putaway pitch. He sometimes utilizes his sinker to climb the ladder, but sinkers have downward movement, whereas four-seamers feature rise, making them more effective up in the zone. And as a lefty, he could go up-and-in to righties, providing an effective velocity boost to alleviate some velocity concerns. In those ways, a four-seamer would literally add another dimension to his game by enabling him to pitch up and down in the zone.

Until I see a change in pitch mix, even if it’s not necessarily the one I suggest, I’m going to remain concerned. With back-to-back seasons of only 150 IP and a crowded Dodgers rotation (coupled with the increasing likelihood that the Dodgers shuffle their pitchers between the DL, rotation, and bullpen), Wood may not make up in quantity next season what he might lack in quality. I’d expect 150 IP, a high 3s ERA with a 1.20 WHIP, and an 8.0 K/9, with very little upside for more given the direction he’s going. Personally, I Wood rather go with someone else.

lol, great scarlet takes a tumble reference. how long were you waiting to do that?

I think you hit the nail on the head in the last couple paragraphs – the ratio performance hurdle for a Dodgers starter is simply a lot stricter than most other teams. We need that low 3.00-era and sub 1.15 whip since we can only realistically count on 150-160 innings (note: no pitcher on the Dodgers has eclipsed 175 innings over the last three years) and thereby depressed K, QS and W stats.

Added it and deleted it to each article I’ve written thus far until I finally made it work