Pitching is the disruption of timing, as the old saying goes. It’s why a changeup paired with heat is so effective, and it’s even right there in the name. One can’t change up speed without, well, speed.

But what if there was an unhittable pitch on its own? How often could a pitcher throw it while remaining effective? Think of the Japanese former professional hitter who for a game show stood in against a 186-mph fastball and couldn’t see it, or Devin Williams’ changeup.

While we don’t yet have proof of concept of such mythical pitches, we can in fact assess the upper limits we’ve seen on pitches going back to 2002 as pitch-by-pitch data has been made available. For our purposes, I’m defining “effective” for a pitcher as a season in which they pitched at least 50 innings and finished with an above-average expected fielding independent pitching (xFIP-), where 100 is league average.

Here are the upper bounds of throwing a single pitch while remaining an above-average pitcher.

Fastball

Mariano Rivera, 2003 Yankees, 96.8% fastballs, 67 xFIP-

This one seems a bit like cheating, as Rivera obviously threw his cutter which wasn’t classified separately from fastballs in pitch tracking until 2005. In some ways though, this is proof of concept. If ever there was an “unhittable” pitch that batters knew with almost certainty was coming, wouldn’t it have been Mariano’s cutter?

https://gfycat.com/leafykaleidoscopicgypsymoth

If you want a “real” fastball though, you don’t have to look too far. Jake McGee in 2014 threw his fastball a Mariano-like 96.4% of the time for the Rays, en route to a season that was 32% better than the average pitcher (68 xFIP-).

That season, McGee struck out better than 11 batters per nine while throwing 71 innings. Unfortunately, public data on pitch movement isn’t available before 2016, two years after McGee’s fantastic season with his four-seamer. In that 2016 season, however, McGee had 7% more vertical movement and 11% (both in the top 10% in MLB) more horizontal movement than average, and was still throwing 97 on average.

Essentially, you can throw a great fastball as much as you want.

Changeup

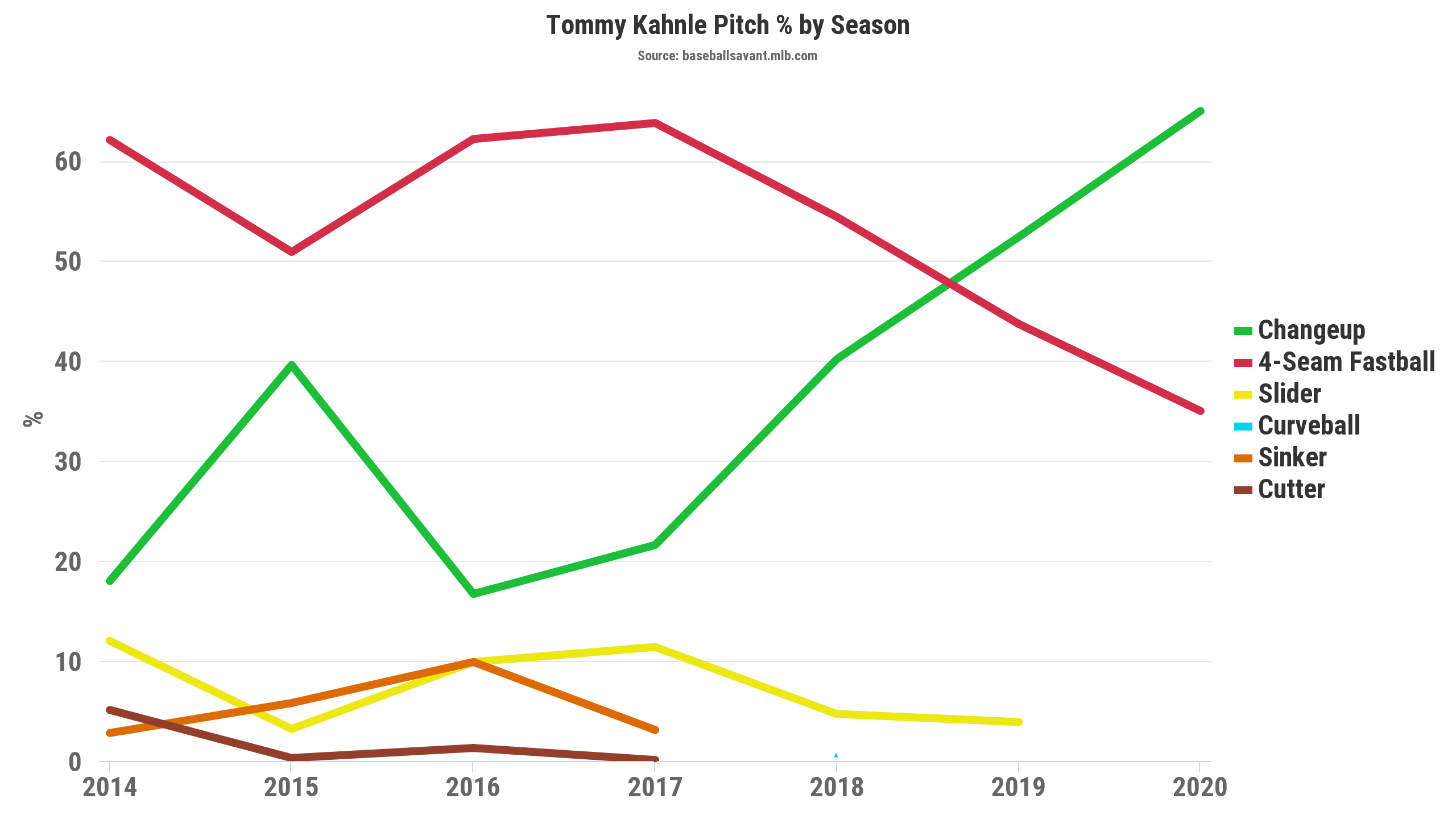

Tommy Kahnle, 2019 Yankees, 51.9% changeups, 59 xFIP-

The change, on the other hand, and possibly unsurprisingly, does not have its own Mariano Rivera that gets by solely throwing that pitch. Technically, if one only throws changeups you’re just a slow pitcher. (Hey, maybe I’m the Mariano Rivera of changeups! Call me, Brewers.)

It takes guts to throw your slow stuff the majority of your pitches, and in fact, only three players have done so in the pitch-tracking era. In fact, only 18 players have thrown it 40% of the time or more, and as a group, they’ve been just a bit above league average, with a 91 xFIP-.

We truly are in a golden age of pitching, though, as the all-time leader for throwing a change and still maintaining effectiveness was Tommy Kahnle’s 2019.

https://gfycat.com/deepsarcasticbobcat

Unfortunately, Kahnle missed most of 2020 due to Tommy John and isn’t expected to return until 2022. At that time, we’ll see if Kahnle will continue his four-year trend of throwing his four-seamer less while increasing that changeup usage and setting a new mark for effectiveness with a majority-offspeed offering.

Curveball

Scott Sauerbeck, 2002 Pirates, 70.6% curveball, 68 xFIP-

Ah yes, who can forget Scott Sauerbeck’s 2002 with the Pirates? In all seriousness, Sauerbeck had an amazing season, as one might surmise from his xFIP-. In just 62.2 innings pitched, he managed two wins above replacement, which was eclipsed on that Pirates team only by Kip Wells, who managed 2.8 WAR in more than three times as many innings.

More amazing is the distance in which Sauerbeck has separated himself from his closest competitor to throwing the curve more often in a season. Ryne Harper in 2019 threw his curveball the second-most all-time, and he did it more than 10% less than Sauerbeck. Lance McCullers is known as a curve-heavy pitcher and has never thrown it more than 50% in a qualifying season. Sauerbeck threw it 70% of the time!

If you’re looking for an unbreakable record in terms of a single pitch, this might be it. Sauerbeck split time the following season between Pittsburgh and Boston, where he cut his curve usage down by nearly 20% (still good for the fourth-most all-time), but wasn’t nearly as effective, as he was below-average across 56 innings.

https://gfycat.com/dopeytotalbufflehead

Sauerbeck’s curve from 2001

Knuckleball

Tim Wakefield, 2002 Red Sox, 88.6% knuckleball, 93 xFIP-

It’s tough to succeed as a knuckleball pitcher. Only two pitchers have thrown their knuckleball more than 4% of the time and held an above-average performance for the season in the pitch-tracking era. Tim Wakefield did it three times, and R.A. Dickey once.

This pitch more than any other is truly an all-or-nothing offering, as there are 27 player seasons of knuckleball usage between 92% and 64%, and then the next-highest usage rate is just 19% followed by 3.6%.

It is a bit surprising that in that time there haven’t been more knuckles that have turned in above-average seasons, and that the only knuckler to turn in a season better than 10% above average was R.A. Dickey in 2012. That season was the second-highest usage rate for fastballs in Dickey’s career, as well.

If ever there was a pitch to throw all the time, the knuckleball would be a good choice for the title. If the pitcher doesn’t even know where it’s going to go, what chance would the batter have? Yet when the knuckler goes wrong, it goes really wrong.

The axiom in baseball is that you don’t develop a knuckleball until you need one, but there may be room for an enterprising team to try out a knuckler as an offspeed pitch to pair with other offerings. In the pitch-tracking era, there have only been four pitchers to throw their knuckleball a majority of the time over multiple seasons, and both Steven Wright and R.A. Dickey had their best years when they threw their fastballs the most.

https://gfycat.com/hardtofindtensekitfox

Of course, there’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation, because if you can throw 95 you’re probably not too worried about developing a knuckler, and with all the time it takes to learn and perfect you’re probably better off with a changeup or slider.

So, these appear to be the upper limits of effectiveness for these pitch types. The most gif-able pitches are only that way because they need another buddy to be their best selves. Maybe there’s a lesson in that.

Then again, maybe there’s just no substitute for heat.

Thanks to @jaredfritz for the question on Twitter!

Pitch classification via Fangraphs

Photos by Jeanine Leech/Nick Wosika/Mark Goldman (Icon Sportswire) | Design by Aaron Polcare