Hunter Brown debuted in late 2022 and was quickly dubbed “the next Justin Verlander.” While a lofty expectation for the 2019 fifth-round pick out of Wayne State University, it was easy to put together. He grew up in Detroit idolizing Justin Verlander and looked like a youthful version of JV when he stepped on the mound.

This side-by-side of Hunter Brown and Justin Verlander is 🤯#MLBCentral | #LevelUp | @astros | @xhunterbrownx | @waynestbaseball pic.twitter.com/P2RySudvxT

— MLB Network (@MLBNetwork) September 6, 2022

Equipped with a similarly high-powered fastball and intriguing secondary pitches, it was easy to mark Brown as the next Astros’ developmental success after a 0.89 ERA in 20.1 September innings. However, 2023 wasn’t picking up where he left off: Brown posted a 5.09 ERA in 155.2 IP.

His ERA doesn’t tell the full story (surprise) as Brown’s 2023 can be cut into two parts: he posted a 3.62 ERA in his first 15 starts and a 6.95 ERA in his last 16 starts. His 155.2 innings was a new career high by a substantial margin (29 over 2022 and 55 over 2021), which indicates that fatigue might’ve hampered Brown down the stretch in his rookie season.

Now, going into 2024, Brown has the tools to build off of a promising start to his career but needs to determine who he is as a pitcher to succeed.

Three Different Approaches

Throughout the season, we saw many different versions of Brown as he tinkered with his pitch mix. The drastic changes in usage displayed his development in real-time.

While we’ll get into this more in-depth later, here’s a quick rundown of his arsenal: Brown is equipped with a powerful pitch mix: he’s got a fastball that can touch 99 mph, a slider that sits around 90 mph, and a power curve at 82 mph. He also has a splitter that he occasionally uses for left-handed hitters and also added a sweeper for a month.

Phase One

To start, Brown came out of the gate with a secondary-heavy approach. He only used his fastball 31% of the time in April, relying heavily on his slider in the zone and his curveball as a whiff pitch. The fastball was used both up and down in the zone, primarily as a called strike pitch. The velocity helped him get whiffs as well, which helped fuel a strong 35.1% CSW% early in the year. Once ahead in the count, Brown would try and catch hitters off guard on a slider or spike a curveball into the dirt. The velocity on the slider made it essentially a cutter, which plays well down and away to righties.

Looking at this at-bat against Donovan Solano on April 9th, Brown starts with a high fastball, then peppers the bottom of the zone with sliders and curveballs.

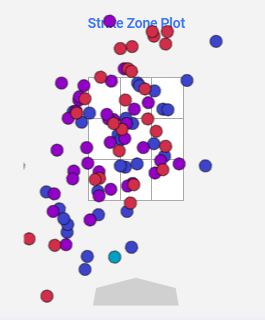

After showing the curve down and away (the gif’d one is the second of two), Brown goes back to a perfectly executed slider and Solano is noticeably late on the pitch. This is an example of the Blake Snell Blueprint: where a pitcher throws elevated fastballs, curveballs in the dirt, and can get slider strikes in the zone. Brown doesn’t fully commit to it as he uses low fastballs to get called strikes occasionally but generally follows the BSB. Although this was a good day for Brown (7 IP, 0 ER, 7 K), the flaw in this approach can be seen in his strike zone plot (FB: red, SL: purple, CB: blue):

He could execute well at times, but a lot of breaking pitches are left up and over the heart of the plate. Although good execution could outrun these problems, they were endemic throughout the season. Brown was in the top 25% of pitches left over the middle-third of the plate on all three pitches in 2023, which leads to hard contact, even on your best days.

After a 2.37 ERA in April, there was a bit of regression in May. In his first start against San Francisco, he had a 45% zone rate and 54% strike rate and was removed after 4.1 IP. The next start was a natural overcorrection: a 53% zone rate and 61% strike rate resulted in his day ending in 4.1 IP against the Angels six days later.

Phase Two

In his next start, we saw phase 2 of his approach. Brown used his fastball 47% of the time, a season-high at that point. His secondaries, which were already inconsistent, failed him again (he got zero whiffs on 48 sliders and curveballs), and he had to turn to heavier fastball usage.

Phase 2 was essentially more fastballs with location dependent on the sliders and curveballs working. When he could get fastballs and sliders in the zone, he would elevate early and hold the curveball in his back pocket when he got to a two-strike count. This at-bat against Jace Peterson shows the full utilization of his arsenal:

Brown goes with a slider that Peterson thinks is off the plate away, nabs the inside corner with a fastball Peterson appears to think was a slider, and then buckles the knees after changing the eye level. A perfectly executed pitch sequence, one that emphasizes that the talent is there.

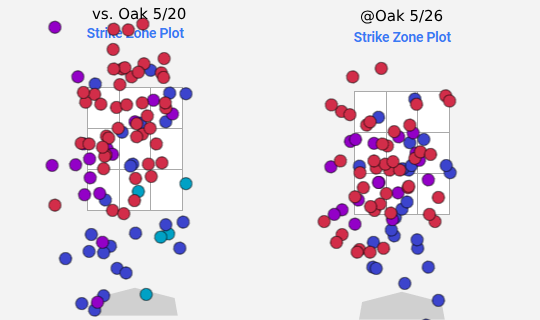

Brown can do this at the top and the bottom of the zone, as exemplified in these back-to-back Oakland starts. There’s only one issue with this dramatic shift in vertical location: the misses start making their way to the center of the zone.

Through June, things were going well. Brown had a 3.62 ERA, 3.54 FIP, 27.4% K%, and 8.5% BB%.

Phase 3

Unfortunately, this is where the season went off the rails for Brown. It could be where fatigue settled in (although only 87 IP through 7/1), but everything exciting we saw from Brown started to disappear.

From July onward, Brown continued to throw more fastballs and more of them were over the heart of the plate. Not only did the location deteriorate, but the pitch itself did too.

Brown lost almost an inch of induced vertical break from June to July and never regained it while seeing a slight decrease in velocity. To add to that, the command completely evaporated in a way that he was either too over the plate or nowhere close.

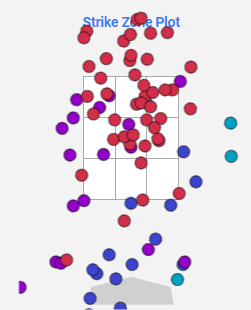

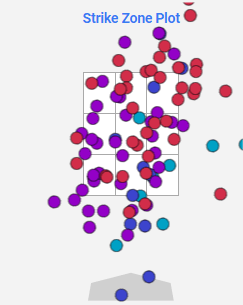

Above is a five-earned-run start against the Mariners where a hefty amount of fastballs are dead center and curveballs are nowhere close. The flip side also occurred, where everything was in the zone, such as this five-earned-run start against the Orioles.

The cost of trying to throw a high volume of elevated fastballs for whiffs was simply too much. All of his pitches leaked into the zone and got hammered. Even though he saw an increase in his fastball’s swinging strike rate, everything else was negatively impacted.

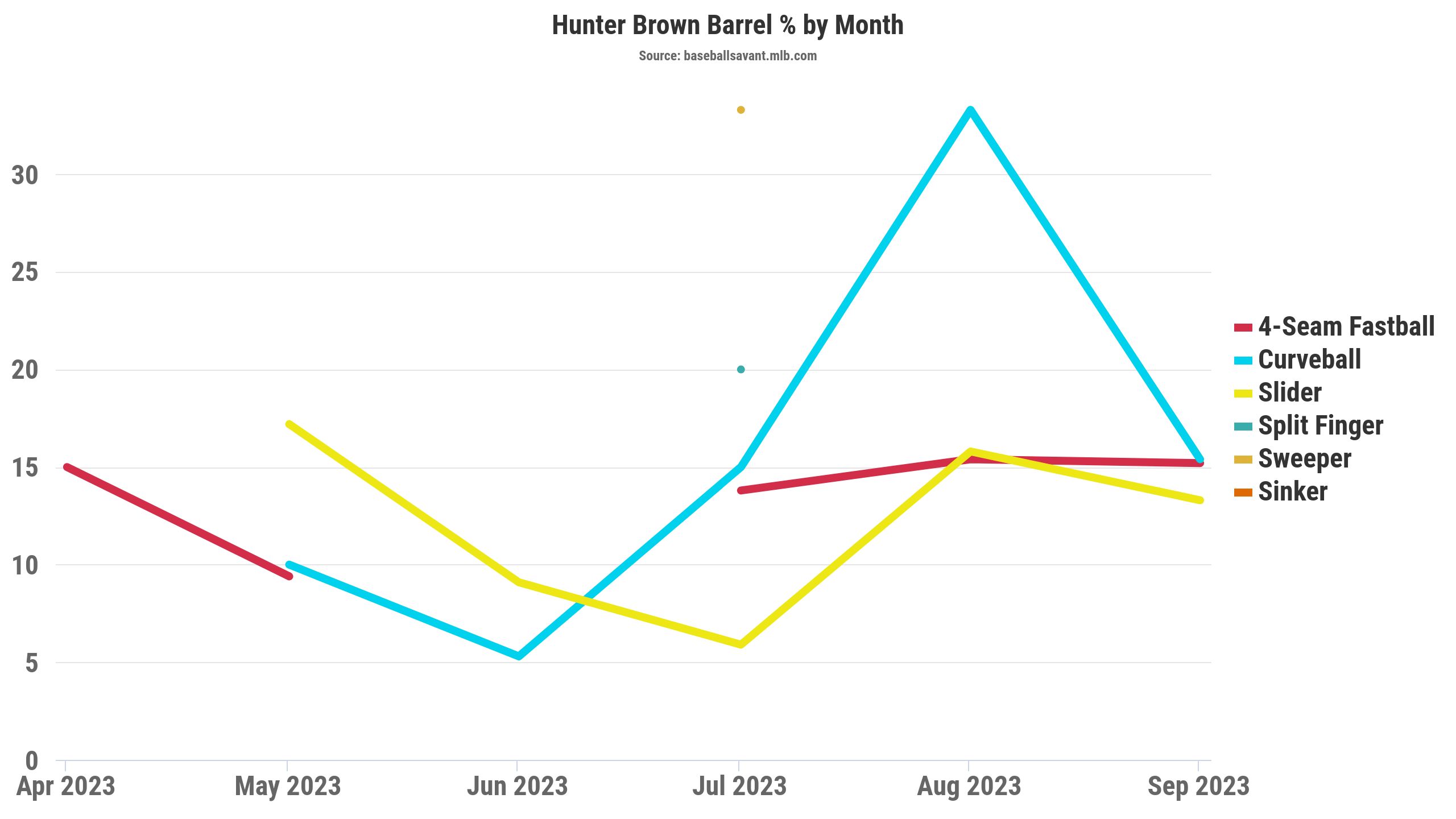

In August and September, all three main offerings posted 10%+ barrel rates, a number usually associated with a good hitter, not the three main pitches of a starter. Brown also tinkered with a sweeper, which has potential, but saw the same fate as his curveball. According to Baseball Savant, 48% of his sweepers were in the heart of the zone or waste, which ranked 3rd among all sweepers (min. 25). The shadow and chase zones are where you want to put a sweeper (or any breaking/offspeed pitch), and Brown was struggling to do that.

The final July-September stats were ugly: 6.95 ERA, 5.42 FIP, 26.0% K%, and 8.0% BB%.

Although the strikeout and walk rates don’t show a huge change, the amount of hard contact he gave up makes way for a ballooning ERA & FIP. His HR/9 went from 0.9 to 2.2, something that on the surface seems like a fluke but the underlying pitch locations make it understandable. In the later months, hitters were waiting for anything close in the zone to pounce on and could lay off non-competitive waste pitches.

Which Version Do We Get in 2024?

For an article titled “Hunter Brown is ready for Liftoff,” the last 400 words do not inspire confidence about the young pitcher for this year. And yet, I’m confident that Brown is going to come out strong this year.

Brown has seen year after year of innings increases, which takes its toll on young pitchers as they get ramped up to big league workloads. 2023 also showed frustration from Brown, as the secondaries falling apart made him turn over to a depleted fastball more. We’ve seen multiple different approaches from Brown and two out of the three have shown to have success. Coming into a fresh season, I trust that he and a smart team like the Astros will commit to a successful approach and stick with it.

First, Brown commits to the Blake Snell Blueprint, where he elevates fastballs, goes in the zone with sliders, and below the knees with curveballs. This worked well with low fastball usage and consistent slider command. The curveball only needs to be a whiff pitch well below the zone.

Second, he increased the fastball usage and located it depending on what pitches were working. This was successful at first: he could adapt to his pitches struggling and still be able to manage on the mound. When needed, he could get whiffs up or called strikes down with the fastball and put hitters in knots with the breaking pitches. However, he occasionally saw everything meet in the heart of the zone and became susceptible to hard contact.

Third, Brown upped the elevated fastball usage and tried to survive with breaking pitches. This approach failed because his fastball simply doesn’t have the shape to work nor does he have the command to make the breaking pitches competitive consistently.

I believe Brown will settle in at a 40% fastball usage, which will allow him to get called strikes low in the zone and elevate when needed. As long as he doesn’t make his approach fastball-centric, the pitch will be effective. Despite the elevated fastballs being the trendy option, Brown hasn’t succeded with it and that’s okay.

He has a 90mph slider that can work all over the zone and a power curveball that can get whiffs, and that’s what Brown needs to emphasize if he wants to succeed in 2024. We’ve seen that it can work, it just needs to be a concerted effort to stick to that plan to see a full season of success.