Few players are as polarizing as Colorado Rockies right-handed starter German Marquez heading into the 2019 season. The 23-year-old Venezuelan earned his share of diehard fans with a 2018 summer performance that rivaled that of the best pitchers in baseball. Yet, many others are prudently skeptical regarding Marquez’s ability to carry his 2.47 second-half ERA forward while pitching home games in Coors Field, a ballpark which consistently inflates run scoring by 30 to 40% over league average. I’m firmly in the camp of the former, believing that the magnitude of Marquez’s dominance, combined with a variety of underlying adjustments he made throughout the season, position him as a legitimate ace going forward.

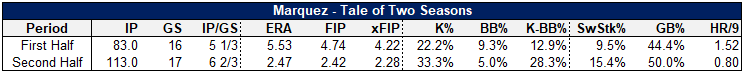

2018 was truly a tale of two seasons for Marquez. In his second full big league season, the young hurler struggled out of the gate, posting a 5.53 ERA across his first 16 starts. The peripheral stats pointed to likely improvement in the second half, as Marquez’s xFIP of 4.22 was over a full run lower than his ERA, but there still wasn’t much to get excited about from either a real-life baseball or fantasy perspective. Things reached a nadir in a June 24th start against the Miami Marlins, where Marquez ceded six earned runs and nine hits in 3-1/3 innings.

But then things changed. In a big, big way. Commencing on a June 30th start against the Los Angeles Dodgers, and ending with an October 1st start against the same team, Marquez hurled an immaculate 113 innings, posting a 2.47 ERA, 2.42 FIP, and 2.28 xFIP. Marquez surrendered more than three earned runs only once, and he earned 15 quality starts out of a possible 17. And encouragingly, the box score dominance was backed up by all of the requisite peripherals. Marquez’s strikeout rate jumped from 22.2% to 33.3%. His swinging strike rate increased from a below average 9.5% to a 95th-percentile 15.4%. He induced more groundballs and gave up fewer home runs. Quite simply, Marquez dominated in every possible facet, and there was nothing fluky about it.

Historical Significance

To operate efficiently, the human brain tends to organize outcomes into neat and often simplistic buckets. Whether we’re evaluating the best pizza places in New York City or the performance of a baseball player, our mind tends to assign favoritism in a simple range of good, average. and bad. It’s not our fault—we’re simply wired to discount scale for the sake of quicker judgments.

But scale, and more specifically, order of magnitude, is important. If a player exceeds a league benchmark by two standard deviations in a small sample, it’s likely that his baseline performance moving forward is higher than a player that only exceeded the benchmark by one standard deviation. What makes Marquez compelling is that not only was his second-half performance two standard deviations above everyone else on traditional estimators like ERA and HR/9, but he also performed just as well, if not better, on advanced metrics like swinging strike rate and xFIP.

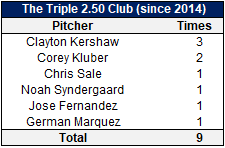

This type of across-the-board dominance, even in a half-season sample, is exceedingly rare. To quantify just how rare, I looked back five years at all the starting pitching half-seasons that met the following criteria: maximum of 2.50 ERA, 2.50 FIP, and 2.50 xFIP, and minimum of 80 innings pitched and 25% K-BB rate.

Six pitchers managed such a feat since 2014. Their names? Clayton Kershaw, Corey Kluber, Chris Sale, Noah Syndergaard, Jose Fernandez, and Marquez.

Marquez wasn’t just good, or even great, in the second half of 2018; he put up one of the best half-seasons we’ve witnessed in five years. You don’t luck into getting put on a list with Kershaw, Kluber, and Sale. As a result, Marquez’s performance baseline going forward is structurally higher.

The Pitch Mix

Marquez’s minor league and early MLB scouting reports focused on the easy velocity of his fastball, which typically sat in the 95 mph range, with the capability of scratching 100 at times. Marquez’s curveball was known as a plus pitch and there were flutterings about a changeup that had potential.

Since then, Marquez has developed a slider and two-seam fastball as secondary offerings and largely left the changeup as a once-per-inning, “show me” pitch. The relationship between Marquez’s curveball and slider is an interesting one, as they differed in velocity by only three mph and at times looked similar in 2018.

https://gfycat.com/separategorgeouscorydorascatfish

The curveball clocks in at 82.1 mph, faster than your average hook, and features a fairly typical 3-to-9 break. He uses it equally against righties and lefties and induces well above average whiffs and weak ground balls on it.

https://gfycat.com/darlingamusedbernesemountaindog

The slider is a bit faster at 85 mph and features less downward break than the curve, although it shows impressive depth on the above strikeout of Ryan Braun in the 2018 NLDS. Marquez prioritizes the slider against same-handed hitters, with a 75% usage rate against righties compared to 25% against lefties.

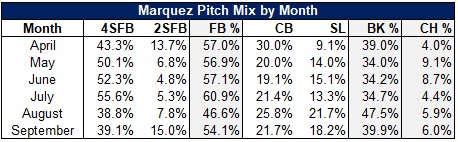

I highlighted the curveball and slider because they were integral to Marquez’s breakout in 2018. However, this was not simply a case of a pitcher vaulting to success by throwing breaking balls more. In fact, Marquez’s breaking ball usage, outside of a surge in August, stayed fairly consistent in the 34 to 39% range throughout the season.

Marquez’s fastball, breaking, and offspeed groupings remained in a stable range each month. The biggest adjustment he made was trading four-seam fastball usage for two-seamers late in the year; however, he had a full month of dominance in July before making that switch.

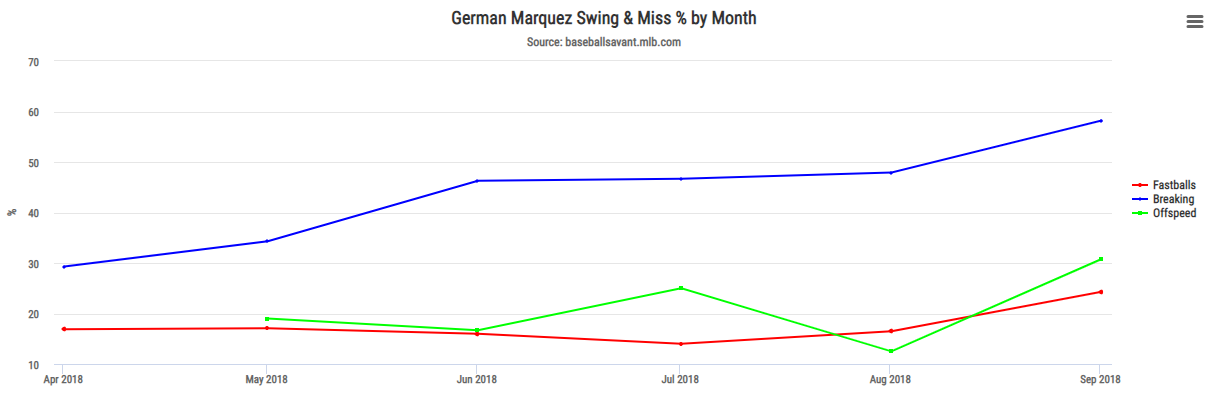

Despite keeping the overall pitch mix status quo, Marquez’s breaking pitches became increasingly dominant as the season went along. In April and May, they earned a 30 to 35% whiff rate (calculated as swings and misses, divided by swings), fairly in line with the MLB average of 34.5%.

By June, Marquez’s breaking ball whiff rate surged all the way up to 47%! It hovered in this range through August, and then vaulted to an astronomical 58% in September! Sorry for the exclamation points, but that’s some serious dominance on his sliders and curveballs. Surely enough, Marquez’s 52.1% breaking ball whiff rate was second in baseball from June 30th onward.

Getting Ahead

It’s evident that Marquez’s breaking ball took a massive step forward around June of last season and that this improvement was one of the primary catalysts behind his second-half dominance. What else did Marquez do to improve?

The top 10 breaking ball whiff performers from June 30th onward also includes names like Julio Teheran, Kyle Gibson, Robbie Ray, and Joey Lucchesi, decent arms who are more akin to number three starters than frontline aces. The fatal flaw for these players is that they have poor control, which is understandable given that they rely heavily on throwing breaking pitches outside of the strike zone.

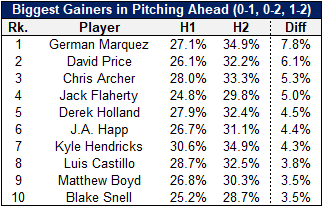

Marquez separates himself from the aforementioned group by combining his elite breaking ball whiff rates with excellent control, evidenced by a microscopic 5.0% second-half walk rate. One of the reasons Marquez was able to keep the walks to a minimum was that he consistently found himself ahead of hitters in the count. In fact, Marquez was by far the biggest gainer from the first to second half in pitching ahead, highlighted by the percentage of pitches he threw in 0-1, 0-2, and 1-2 counts.

Marquez’s 34.9% second-half pitching ahead rate was fourth in baseball among pitchers with a minimum of 1,000 pitches thrown. Justin Verlander, Jacob deGrom and, Miles Mikolas were slotted ahead, while Kyle Hendricks, Gerrit Cole, and Aaron Nola immediately trailed. Fancy that: another stat where Marquez ranks next to baseball’s best starters.

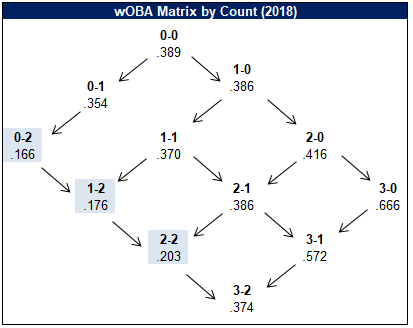

Pitching ahead in counts works to the pitcher’s benefit in two ways. First, it edges the pitcher closer to a strikeout and away from walks, which is obviously a good thing. Second, hitters get defensive with two strikes, enabling the pitcher to suppress hard contact. Sure enough, the league average wOBA differentials by count are striking, with hitters declining from a .389 wOBA at 0-0, to a .354 wOBA at 0-1, and a .166 wOBA at 0-2. Batters are particularly susceptible with two strikes, maxing out across a .203 wOBA in 0-2, 1-2, and 2-2 counts.

As a result, the genesis of Marquez’s success is more clear. He’s combining elite breaking balls with elite command of the count, which allows him to pitch ahead and keep hitters off balance. That combination is kryptonite to MLB hitters.

Aggressiveness

Marquez sat at a 27.1% pitch-ahead rate in the first half prior to ascending to 34.9% in the second half. That’s a massive improvement. How did he do it? Marquez’s overall pitch mix did not shift much over the course of the season. Similarly, his overall zone rate (the percentage of pitches thrown in the strike zone) didn’t change much either, increasing slightly from 46.9% to 47.1% according to FanGraphs.

But overall numbers can be deceiving. It turns out that, while Marquez’s averages didn’t change, his pitch arsenal and location at different points within an at-bat diverged significantly. For instance, Marquez increased his early-count zone rate from 52.6% to 58.0%. This increase led to a drastically improved first-pitch strike rate, rising from 60.1% to 68.6%.

Marquez proceeded to take the opposite approach later in the count with two strikes. In the first half, he threw 50.0% fastballs in 1-2, 2-2, and 3-2 counts, but lowered that to 39.6% in the second half. Correspondingly, his breaking ball usage late in counts went up from 45.3% to 57.7%. His zone rate on those breaking balls also plummeted from 42.6% to 33.8%.

To put it another way, Marquez became much more aggressive as the season went along, challenging hitters early in counts and displaying the confidence to throw his breaking ball out of the strike zone later in counts. The early-count aggressive approach allowed Marquez to get ahead, which put hitters in a defensive posture. From there, Marquez utilized his upper echelon breaking pitches to drop the hammer and rack up strikeouts.

Conclusions

This article attempted to do two things. First, it sought to highlight the magnitude of Marquez’s dominance from June 30, 2018, onward and then contextualize how special that performance was. Second, it dug into how Marquez adapted his approach to achieve those results. It appears that much of his success was derived from working ahead in counts and then using his upper echelon slider and curveball to induce strikeouts.

Many will highlight Coors Field as an obvious detriment to Marquez’s success moving forward. I’m not buying it. When a pitcher achieves a sub 2.50 FIP and xFIP, backed up by a 28% K-BB rate, he largely insulates himself from park factors by keeping the ball either in the catcher’s mitt or on the ground. Moreover, 47 of Marquez’s second-half innings came at home, with his numbers proving even more dominant in Denver, pitching to a 1.90 ERA / 2.02 FIP / 1.48 xFIP. While it will be difficult to expect that level of dominance in the future, 47 innings with those metrics indicate that Marquez can probably be a consistently above average pitcher at Coors.

Some have also started comparing Marquez to fellow Rockies hurler Jon Gray. Both are young righties with hard fastballs and a slider/curveball combination. Gray had a promising finish to 2017 and many wondered whether he could be the starter to “break” Coors in 2018. But by mid-summer, Gray was in AAA and he ended the season with a 5.12 ERA. But there are key differences between Marquez and Gray. First, Gray never experienced a run of success like Marquez did last year (remember: few pitchers have, and their names are in the realm of Kershaw and Sale). Moreover, Gray’s 3.67 ERA / 3.45 xFIP in 2017 was backed by a pedestrian 8.8% swinging strike rate, indicating that there were reasons to be skeptical about his performance outside of a potential Coors-induced regression.

We also can’t get lost on the fact that Marquez is only 23 years old. Most pitchers are still toiling in the minors at that age. Yet Marquez already has a half-season of dominance up there with the game’s greats. Hitters will likely adapt to some of the adjustments that Marquez made last year; however, I’m sure he’s up to the task of fighting back. Pitcher List’s Michael Augustine wrote a terrific article in December that highlighted some areas where Marquez can improve. One of those areas is to learn to elevate his four-seam fastball more, especially against right-handed hitters. This type of adjustment would likely vault Marquez into Justin Verlander territory and make him a perennial Cy Young candidate.

Graphic by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

Great analysis here. I have Marquez at a very keepable $10, but have been wavering on him after being burned by Castillo last year at the same price. The only other comp I can think of to this run of dominance by Marquez was Kris Medlen in 2012 when he pitched 138 innings with a 1.52 ERA, 2.42 FIP, and 19 K/BB ratio. The next year Medlen put up a solid season, but nothing remarkable at all. I still feel like Marquez is a high risk choice, but you make a great case that the upside is massive

Interesting comp!

It’s really a shame Medlen succumbed to injuries because he looked like a very good pitcher with his high swinging strike and ground ball rates. His career pitching line was a 3.33 ERA / 3.40 xFIP / 3.60 FIP.

The difference is that Marquez’s swinging strike and strikeout dominance puts him in a better position to hold his numbers.

Crazy to think that he’s only 23 years old. Marquez had a .796 OPS vs L. Any idea why this was? His ceiling may always be limited in Coors, but it’ll also be limited if he can’t figure out how to pitch to L. Nice article. Thank you bud

I was shocked when I learned he was still just 23. It seems like he’s been around for a while.

Marquez’s tale of two seasons also applied to his splits against lefties. In his first 16 starts, lefties produced a .374 wOBA off Marquez. That plummeted to .312 in his next 17.

Also, in 2017 Marquez was actually significantly better against lefties than righties.

Those numbers, combined with his dominant curveball, which gives lefties fits, makes me comfortable there isn’t a platoon issue.

My man!

You do amazing work. Please don’t stop.

Chuck

Agree. This is probably the best thing on the site so far in 2019

I have the option to keep Marquez at 12th round keeper or Taillon in the 9th… I was leaning Marquez before reading this great piece, and I’m still going that direction, but I’d love the extra certainty of your blessing.

Alan,

I take Marquez in the 12th and don’t look back. I’m fairly confident he exceeds Taillon’s overall production by quite a bit this year.

Nick P. would likely have a different take though! ; )