Very little has gone according to plan for José Berríos in 2022. Expectations were high after Toronto used two of their top prospects to acquire Berríos from Minnesota at last season’s trade deadline. They followed that up with a seven-year, $131-million extension during the offseason.

His season got off on the wrong foot on Opening Day when he did not survive the first inning against Texas. Six of the seven batters he faced reached base via three hits (one a homer), two walks, and a hit batter (plus a wild pitch for good measure), and what was expected to Berríos’ big day was finished after just 34 pitches.

Opening Day was only a sign of things to come.

Aside from his rough fourteen-start rookie season back in 2016 (8.02 ERA / 6.20 FIP), Berríos has been a model of durability and consistent competence. From 2017 through 2021, every seasonal ERA he’d produced had been between 3.52 and 4.00, and those were supported by seasonal FIP marks that landed between 3.47 and 4.06.

A Down Year

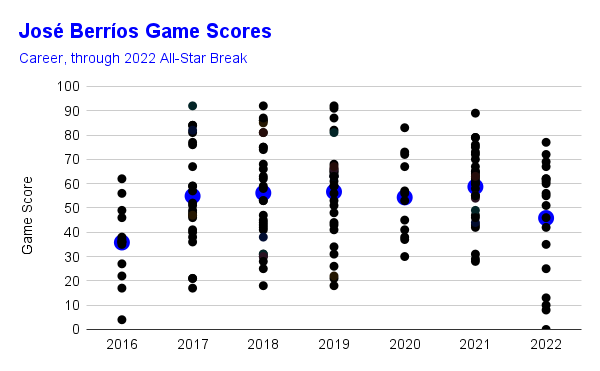

But this season, he’s been anything but consistent and competent. Game Score is a general and simple tool for evaluating starting pitcher outings where 50 is average. Below is a plot of every Game Score of Berríos’ career. Again setting aside the rookie campaign, you can see via the larger blue dots in the plot that Berríos’ seasonal average Game Scores were remarkably consistent (and above average) between 2017 and 2021. You can also see how the range of the dots in each season had gotten tighter over time. The seasonal standard deviations of his Game Scores had decreased from around 21 in 2017 and 2018 to 14.5 last season, indicating more consistent performances.

Data from FanGraphs

This year, his average Game Score sits at a below-average 45.8, and the standard deviation is 23.6, reflecting that he’s been significantly worse overall and much more inconsistent at the same time.

You can also see in the chart above that he’d had just five games in his career with Game Scores worse than 20, with the last of those occurring in 2019. This season, he’s already had four such games (lower right of the chart), including a brutal zero mark from an 8-run, 2.2-inning blowup against Milwaukee on June 26.

At the All-Star break, Berríos was sporting a 5.22 ERA and 4.73 FIP, marks that were among the worst in the league for starting pitchers. By WAR, Berríos (0.4 fWAR, -0.3 bWAR) has essentially been a replacement-level pitcher this season.

The relative closeness of the ERA and FIP numbers suggest the struggles have not been fluky, and that idea is further supported by Berríos’ underlying Statcast metrics, which have backed up in all the wrong ways, especially in terms of strikeouts, whiffs, and preventing hard contact:

As of July 23

Searching for a Cause

In digging into what might be behind the struggles, it was interesting to find that Berríos is more or less the same as he’s been in terms of approach and stuff. His pitch-type mix is nominally similar to the past, although he has made a shift to offer his four-seamer (31.8%) more and his sinker less (23.7%). Given the results those two offerings have generated this season (Four-seam: +2.8 run value/100 pitches, Sinker: -1.4 RV/100), that exchange seems to be ill-advised.

His average pitch velocities are the same or slightly better than last season. He was one of the pitchers whose raw spin rates were most affected by the sticky stuff ban last season, but his spin rate, efficiency, and direction numbers are all in line with last season’s second half when he was very effective in Toronto (3.58 ERA, 3.28 FIP, 26.8% K% in 70.1 IP). His signature sweeping curveball is still excellent (.161 BA, 33.3% whiff).

Berríos is getting more movement on his pitches than he previously has, something that would seem to be a positive development, not a hindrance. All four of his pitch types have both greater horizontal and vertical movement than last season, as the Statcast data below shows:

Altogether, Berríos’ Stuff+ metric was 104.8 as of July 16, just a tick below last season’s ending point of 105.9.

Beyond stuff, Berríos’ plate discipline numbers also do not reveal an obvious issue. His 5.5% walk rate is the lowest of his career and his rates of strikes (68.3%), first pitch strikes (69.8%), pitches in the strike zone (48.3%), early count strikes (26.2%), and plus pitches (61.2%) have all increased over last season. The Statcast summary shown earlier showed that he’s still getting chases out of the zone (32.7%) at well above average rates.

So, the approach and stuff are mostly the same and he’s in and around the strike zone more than ever. Yet, his strikeout rate is down to 21.1% from 26.1%, his whiff rate has gone from 23.7% to 21.4%, his average exit velocity allowed is up to 90.5 mph from 88.4 mph, his average launch angle allowed has increased from 12.4 degrees to 15.3 degrees thanks to the highest fly ball rate of his career (26.3%), and he’s already allowed 20 homers (career-high is 26 in a season).

Clearly, something is different, but it doesn’t seem to be any kind of change in physical ability.

Lost Command

It has long been generally accepted that control refers to a pitcher’s ability to throw their pitches in the strike zone. That is subtly distinct from command, which refers to a pitcher’s ability to throw their pitches to precise locations. The laundry list of data I’ve thrown at you above suggests that Berríos’ control has been fine, but his command has been suspect. He confirmed as much before a June start against Minnesota, saying “I’ve been throwing a lot of strike fastballs but not quality fastballs and that’s led to a lot of damage.” … “That’s one of the things I’ve been working on.”

The data backs him up on that diagnosis. The table below contains a pitch result breakdown comparison of this season’s fastballs against the average of the prior five years:

This data clearly lays out that Berríos’ fastballs are more inviting to hitters than they have been in the past. This season there have been more foul balls, hits, and balls in play and significantly fewer called balls.

In contrast to what we might most often think when a pitcher is having command issues, it seems Berríos’ challenge this year is that he’s been missing more on the plate, instead of out of the zone. His command shortcomings are causing him to throw too many strikes and give batters too many good pitches to hit, especially with his fastballs.

If you dig back through the archives of articles about Berríos, something that will stand out is the commentary about his unique delivery. In an era where many pitchers have been coached for high-efficiency, minimal motion mechanics, Berríos stands out for his flowing, athletic delivery with lots of moving parts. He throws across his body from the extreme third base side of the rubber (somewhat of a rarity for starting pitchers), an angle that adds deception and helps him take full advantage of the horizontal movement profiles of his fastballs and big, sweeping breaking ball.

José Berríos, 94mph Two Seamer and 83mph Curveball, Overlay. 😳

Two Seamer = 20 inches of run

Curveball = 17 inches of break pic.twitter.com/QTauIjvCM3— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) July 12, 2022

The volume of moving parts plus the unique point of release have meant that Berríos’ mechanics occasionally get out of whack. You can see above that his delivery includes a long arm swing that sometimes wraps behind his body and throws off the timing of the rest of the chain. An off-and-on theme throughout his years in Minnesota was his work with pitching coaches to “stay on a straight line to home plate” and avoid “getting too rotational” in his delivery. When he has struggled with these issues, his command has suffered and he’s been hit harder.

Those mechanical challenges seem to be what has been happening this season, as former Mets General Manager Steve Phillips recently wrote for TSN. That Berríos’ pitches are moving a bit differently (especially horizontally) than before also complicates matters. It makes sense that he’s struggled to command his pitches as precisely as in the past.

The good news is that he’s found his way out of similar, albeit less prolonged, stretches before. Those have usually involved some kind of mechanical adjustment to simplify his sometimes noisy mechanics or changing his starting point on the rubber to a line that enables him to execute as desired.

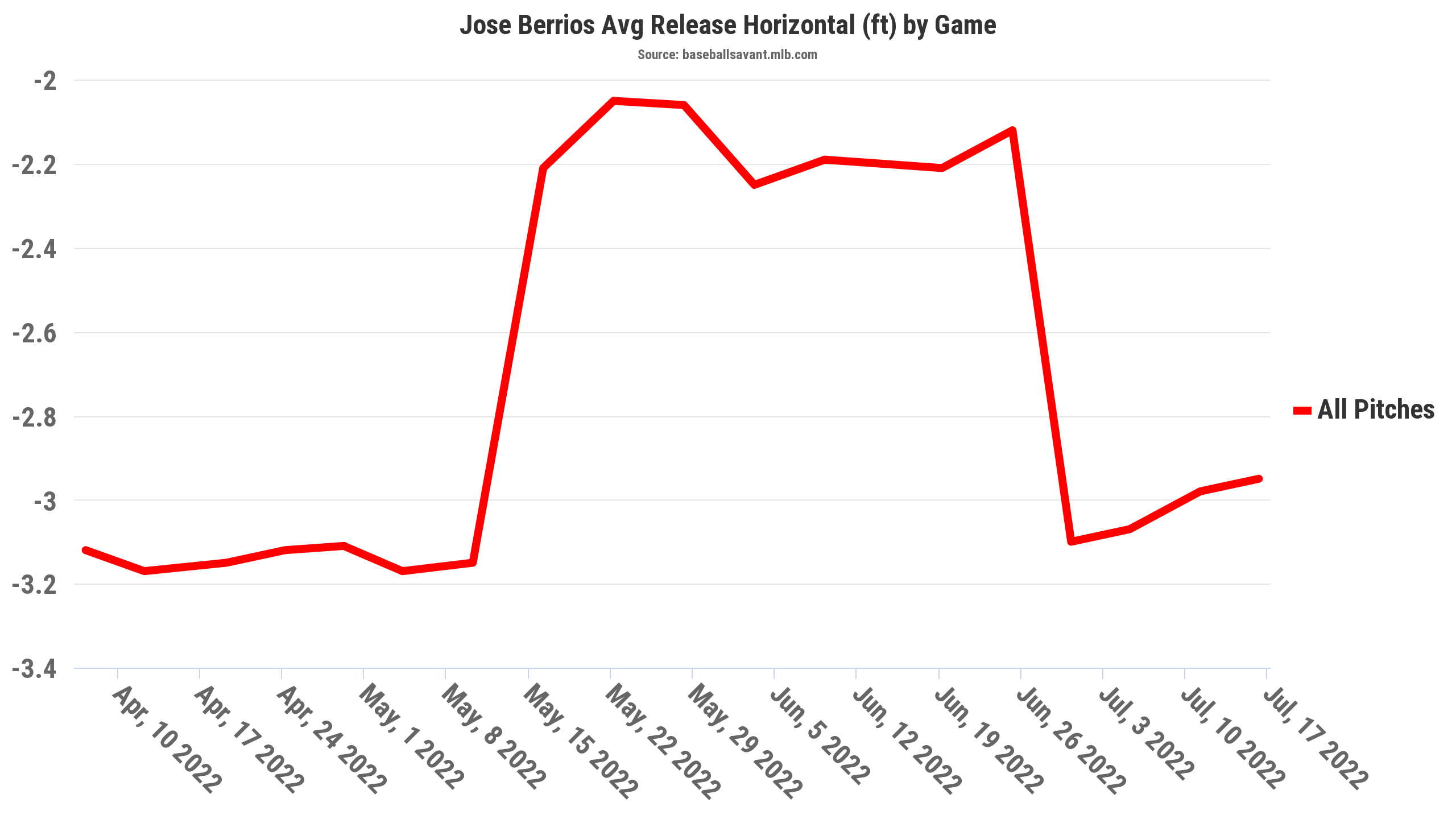

This season’s data shows that Berríos’ experimented with a more centered starting position, moving more than a foot toward first base for seven starts mid-May through mid-June. Such an adjustment was no doubt targeted toward helping him work on a more direct line toward home plate.

Beyond adjustments like that, Berríos’ starts are full of on-field body language consistent with a player trying to fight through a mechanical issue. You can see him constantly reminding himself of what he should be doing. Here’s a clip from that miserable day in Milwaukee in June where Berríos demonstratively reminds himself to work online after a bad miss:

https://gfycat.com/alienatedimmensechinesecrocodilelizard

What’s Next?

In the second half, Berríos will be looking to turn his season around. With his mechanical issues identified, he may already be on that path. He’s slid his starting point back toward the third base side and featured his four-seamer less (24.5%) and results have started to follow. In five July starts, Berríos worked 29.0 innings, with much more characteristic 3.41 ERA, 3.15 FIP, 29.0% strikeout rate, 45.0% ground ball rate, 88.8 mph average exit velocity allowed, and an average Game Score of 55.

Berríos will be trying to build some consistency and extend from that strong stretch. Given his history of competent consistency, ability to identify problems and physically make adjustments throughout a season, and still-quality stuff, we shouldn’t be surprised if José Berríos turns the corner and is much more like himself down the stretch. If he does, more precise command will likely be a big reason why.

Photo by Joe Robbins/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

take a look at his spin rate by month going back to last year, then look at his whiff rate by month. he lost a little something when they took the sticky stuff away. it may not be the full story, but he’s little change in his pitch usage, control, or batted ball breakdown, and is just not whiffing guys like he used to and getting crushed more often.