For Game 1 of their Wild Card Series against the Astros this year, the Twins did something that hadn’t been done in nearly four years when they handed the ball to Kenta Maeda to start a postseason game.

Maeda had carved out a role as a solid member of the Dodgers’ rotation ever since he came over from Japan in early 2016, but for each of the team’s three playoff runs from 2017 through 2019, he was relegated to bullpen duty despite his objections to doing so each year. Maeda expressed his desire to prove himself as a reliable, full-time starter following the 2019 season, and a trade to Minnesota in February gave him the opportunity to do so.

Once the 2020 campaign finally kicked off, Maeda was able to capitalize on his fresh start in a huge way, posting a 2.70 ERA and 3.00 FIP in 66.2 innings while finishing second in the AL Cy Young voting. In just one year, Maeda transformed himself from a longtime mid-rotation guy that couldn’t secure a playoff start to a top-of-the-rotation-caliber pitcher that the Twins felt confident in opening a series. This shift seems sudden when considering how his career path with the Dodgers had gone leading up to this past year, but when you dig deeper into Maeda’s 2020 performance, you’ll see some intriguing changes that bode well for his ability to replicate it.

Mixing it Up

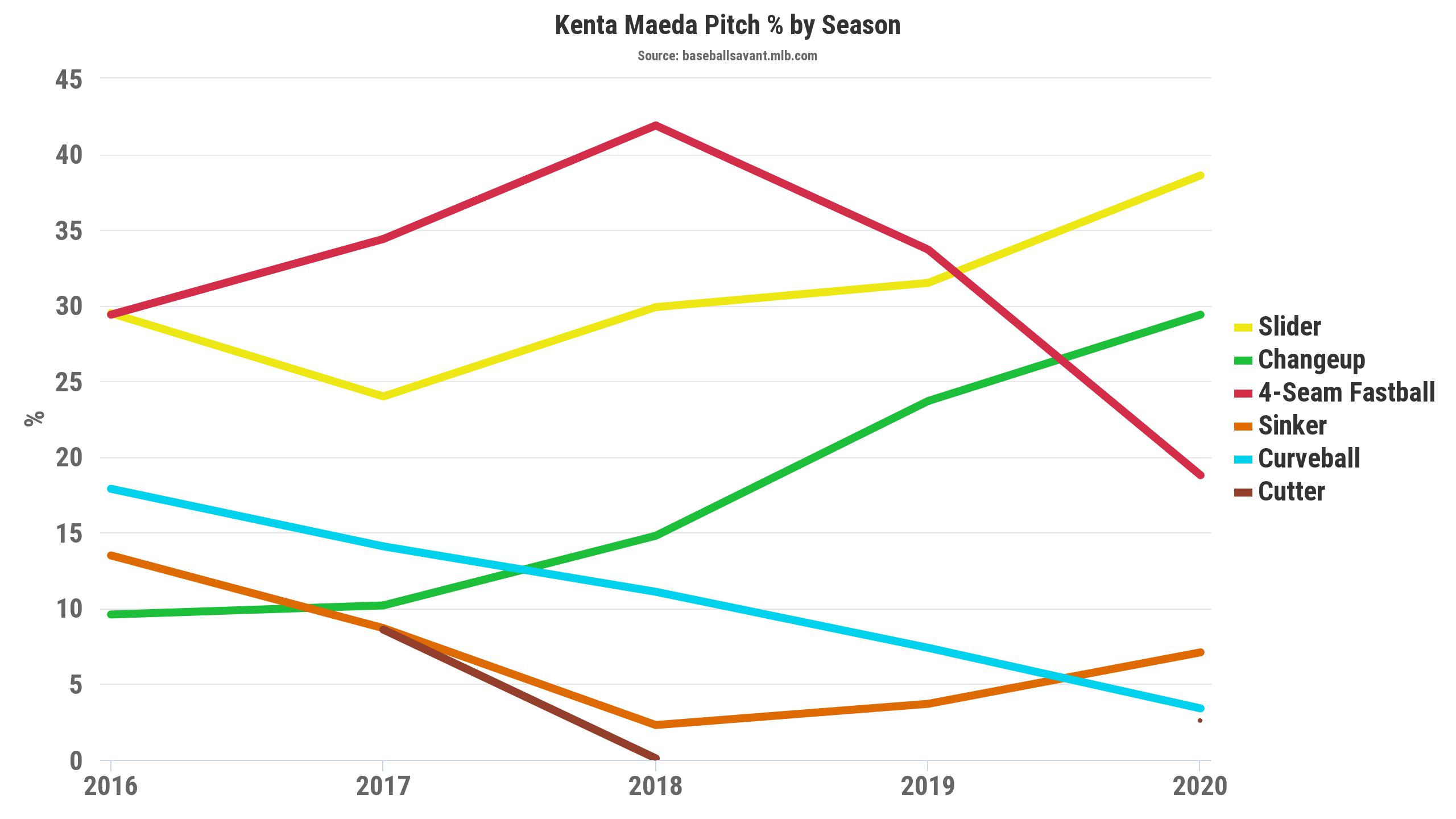

The single biggest adjustment that Maeda made in 2020 was to his overall pitch usage, specifically regarding his main offerings. For Maeda’s entire major league career leading up to this past season, his most commonly thrown pitch was his fastball, which peaked in usage at 41.9% in 2018 and finished 2019 at just under 34%. This amount of usage with his fastball is pretty significant when you consider the fact that Maeda has four other pitches that he has used on at least a semi-consistent basis throughout his career, so a logical assumption to make would be that he has had a lot of success with the heater to justify it.

This is not the case, however, as Maeda’s fastball has actually been one of the worst pitches in his arsenal. Its velocity has always graded out as subpar throughout Maeda’s big league tenure (it landed in the 36th percentile at just 92.1 mph on average in 2019), and both its horizontal and vertical movement fell to the point of being below average as well. Its consistently above-average spin rate has been the heater’s lone redeeming quality, but even that wasn’t enough to keep it from getting rocked to the tune of a .517 slugging percentage and a .381 wOBA in Maeda’s final season in Los Angeles.

Maeda’s high reliance on his fastball despite these less than stellar results was concerning on its own, but it gets even more perplexing when you look at how his two most frequent secondary pitches fared at the same time.

| Usage | SLG | wOBA | Whiff% | Average EV (mph) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastball | 33.70% | 0.517 | 0.381 | 21.10% | 89 |

| Slider | 31.50% | 0.288 | 0.211 | 40.70% | 83.4 |

| Changeup | 23.70% | 0.317 | 0.239 | 36.20% | 86.2 |

Maeda’s slider and changeup were significantly better offerings than his fastball in 2019, yet they both saw less usage than it. His slider was by far his best pitch and graded out as one of the better sliders in all of baseball by run value, and his changeup, while not as good, was still very effective as a secondary breaking pitch. Both pitches were very good at getting swings and misses, and they both were big driving forces behind Maeda’s ability to induce weak contact, which has always been his biggest strength as a pitcher.

When taking all these facts into account, the changes that Maeda needed to implement to make the jump from good to great look both simple and obvious: throw his best pitches more often and his worse pitches less often. Maeda certainly recognized this himself, as he did that and then some in 2020.

The changes that Maeda made to his pitch mix were pretty drastic – a nearly 15% drop in fastball usage alongside a 7.1% increase in sliders and a 5.7% increase in changeups. This shift in philosophy wasn’t anything revolutionary (Dylan Bundy last year and Patrick Corbin in 2018 are two examples of guys having success after doing something similar), but it is what helped Maeda reach new heights in his game, as the way that he attacked hitters suddenly made a lot more sense. His best and second-best pitches were now the ones that hitters were seeing most of the time, and his traditionally weak fastball wasn’t asked to do as much heavy lifting. Speaking of that fastball, you’ll see something interesting when you look at the 2020 equivalent of the numbers from earlier.

| Usage | SLG | wOBA | Whiff% | Average EV (mph) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastball | 18.80% | 0.114 | 0.101 | 25.70% | 83.4 |

| Slider | 38.60% | 0.466 | 0.299 | 33.50% | 84.8 |

| Changeup | 29.40% | 0.156 | 0.136 | 45.60% | 83.1 |

Maeda’s slider and changeup were effective once again (the slider regressed a bit but remained a good pitch while the changeup actually took its place as one of the better secondary pitches in baseball), but his fastball suddenly took a huge step forward. The average exit velocity against Maeda’s heater fell by almost six miles per hour, and the slugging percentage and wOBA allowed against it ranked among the league’s best. On the surface, this seems really random, especially when you consider the fact that the pitch’s average velocity and spin rate actually fell from where they were in 2019. There is a reason for this, though, and it has to do with how Maeda specifically utilized his fastball.

The first image in this GIF is Maeda’s pitch usage in specific counts during the 2019 season, and the second one is the same for 2020. The main difference between the two that jumps out right away is that Maeda all but stopped throwing his fastball in the hitters’ counts (1-0, 2-0, 3-0, and 3-1) seen on the right side, replacing it mainly with his slider.

This was a very smart change and one that can explain his fastball’s sudden improvement very well. Hitters are typically looking for pitches to do damage with when they get to these favorable counts, and more often than not, their pitch of choice is a fastball. By forgoing his heater for his slider in these traditional fastball situations, Maeda minimized the number of opportunities to do damage against it, which made it an overall better pitch as a result. This turned out to be huge for Maeda, as it helped keep opposing hitters in check by making sure they couldn’t key in on any one pitch of his too closely. The plate discipline metrics of opposing hitters show this better than anything, as the figures Maeda posted in those categories placed him in some unfamiliar territory:

| O-Swing% | O-Contact% | SwStr% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 34.80% | 55.90% | 14.60% |

| 2020 | 40.80% | 48.20% | 17.20% |

| 2020 MLB Ranking | 1 | 3 | 3 |

Hitters swung at a lot more of Maeda’s pitches outside of the zone than they had previously, but made contact significantly less on those very same pitches. What this illustrates is that Maeda had hitters fooled more in 2020 than at any other point in his career, and the optimization of his pitch mix was the biggest catalyst for this. By changing both how often he used his most common pitches and when he threw them, Maeda found himself with three legitimately good options in his arsenal, all with characteristics distinct enough to keep his opponents off balance more often than not. This is something that Maeda never had to the extent that he did in 2020, and it proved to be the last piece of the puzzle in unlocking a new level of performance for him.

Future Outlook

Like with many things this year, it’s difficult to determine how real Maeda’s performance in 2020 was due to the small sample size resulting from the shortened season. His breakout occurred over the span of just 66.2 innings, after all, which is a very small percentage of the nearly 600 good (but not great) innings that came before it. The change that he made to his pitch usage is a very encouraging one, though, and the simple nature of it makes it feel like one that can be repeated in 2021 and beyond. Only time will tell whether the ace version of Maeda that we saw this year is the one that we can expect to see going forward, but if his adjustments prove to be sustainable, the Twins will likely have no choice but to hand him the ball for their biggest games, just as he has wanted all along.