Albert Pujols is a Dodger. It feels really weird to write that, as most people in baseball would have assumed Pujols was going to finish his Hall of Fame career with the Angels, but things ended up differently.

A mediocre performance, combined with a surging new talent in Jared Walsh, who’s been scorching hot recently, were looking to relegate Pujols to a bench role, which he apparently didn’t want with the Angels, so they parted ways, leading to the Dodgers signing him up for the rest of the season, oddly enough for a secondary role. This news immediately brought up the corresponding buzz in (fantasy) baseball Twitter/world and the debate around bad contracts restarted, focused on the, supposedly, aging stars’ bad contracts.

It is undeniable that Pujols’ tenure with the Angels was very underwhelming: he accumulated an fWAR of 81.3 with the Cardinals before signing a huge ten year, 240 million dollars contract with LA in 2012, during which he has a 5.6 fWAR, including this year, to show. Simply, that’s $42,857,142.86/fWAR. Although his career 86.9 fWAR is good for the 28th best ever in MLB, the disparity between the two stages, St. Louis and LA, is just too big to ignore.

This fuels the discussion: are mega-contracts in which a team pays that much for so long for an aging star, good at all? Is there any real value or are they a complete waste?

The Problem with Age

We will all succumb under the weight of Father Time (except for Nelson Cruz, of course). Every player will experience a decrement in their output, whatever the way we measure it, as his age increments; that’s known as the aging curve. There have been lots of studies and research around how the aging curve shape represents that behavior and most of them agree that peak performance is achieved around the age 26 to 29 seasons, and the decrement starts at around 30, getting steeper by the age 31-32 seasons.

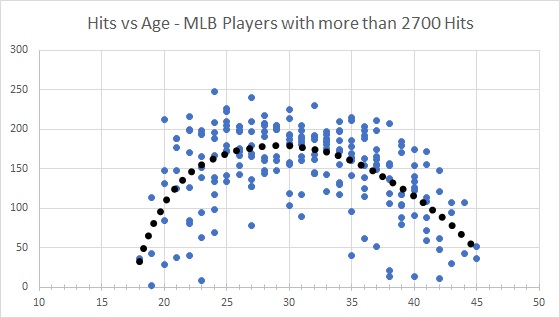

Just for the sake of an example, I took a random sample of ten batters that were able to connect at least 2700 hits during their career and graphed the hits versus age scatter plot and the corresponding trend curve for all of them, it looks like this:

Some names from the list of players in that dataset include Pete Rose, Ty Cobb, Wade Boggs, Babe Ruth, Harold Baines, and Luke Appling. The adjusted curve pretty much resembles what the studies found out, with a special similitude to what the Delta Model with Survivor correction proposes: peak performance at around 26-27 years old, then a steady descending curve for the following years.

This knowledge is not new, of course, teams and people, in general, are very aware of this situation, but it is still surprising the dollars and time invested in contracts for players that are around the declining stages of their careers; some say scarcity moves the needle in that regard, but it might be a combination of factors which we won’t be discussing here. What interested me the most was to try to quantify, what has been the return of investment for those teams that have open their wallets to get these so-called aging stars; how good or bad have those contracts been for them in general? Specifically, I wanted to check on contracts awarded for the age 31 and on seasons, to be on the other side of the hill, so to speak.

With that in mind, I searched on Spotrac, all contracts signed since 2010 for players in their 31 years old season, and refined the data set to just batters, as there are differences on how to evaluate them from pitchers. I ended up with the top 39 contracts by total value and some of those are in the following table (the full list is here):

Some interesting names, on that list. For the purpose of this article, I will use the 2019 season as the ending year for all contracts that reach that far, omitting the performances in 2020 (due to the shortened season) and the current ones.

The next question was, “Which stat or stats should I use to gauge the performances?” Previous studies have used OPS, OPS+, wOBA, wRC+, etc., but I settled for fWAR as it would encompass most of the stuff that we tend to value from a player, on offense and defense. First, I found out the accumulated WAR per player during the duration of those contracts, and on a per-year basis:

Just remember this is just a sample of the total data set, which includes almost 40 contracts. The full list encompasses 122 years of playing time and 191.80 of fWAR production, good for an average of 1.6 fWAR/Year. If we take into account that the AAV for all of them is $16,169,600.00, we get that every Win Above Replacement from this pool of players during these contracts cost about $10,285,147.03 (there is no inflation adjustment here, this is just a good approximation).

So, is that bad, good, nefarious, glorious? Well, it depends, of course.As with many things in baseball, there is not a consensus on what’s the best-approximated value for a Win Above Replacement (WAR). I’ll refer to some very extensive studies, and they tend to point into the 7.5 to 9 million dollars range for the past two years of free agency, so I’ll settle to a middle point of 8.5 million dollars.

With that benchmark, we have a rough estimate that teams overpaid, on average, around 21% for each win above replacement for these 39 contracts. This number should go a little higher if we do some inflation adjustment, so a ballpark figure of 25-30% is reasonable. A thorough study should go deep into things that are beyond the scope of what I tried to do here: there are hidden costs and values in a lot of this type of contract.

As an example of hidden costs in Pujols case: because of the size of the contract, the Angels, for many years, felt like they had to play him every day, while a well beyond replacement player like Jared Walsh missed playing time. We already know that Pujols’ has put up a minimal (to negative) statistical contribution this year but, on top of that, other players on the roster did not play because of him. Jared Walsh has been able to contribute the 1.4 fWAR he’s produced so far, good for 30th among all qualifying batters in MLB. Pujols’ playing time was a double tax on LA’s global output.

On the other hand, there are hidden values to account for too, as the economic returns on merchandise sales and television contracts that a signing like Pujols’ means should be part of the equation. It’s not a secret that the $3 billion 20 years television deal the Angels signed in 2011 is closely entangled with the Pujols signing, as both contracts benefited from each other: Pujols was one of the biggest names in baseball at the moment, a very desired player to have in any TV broadcast, sparking the interest from the network to have him on screen with the Angels. The influx of the TV money would easily make it possible to pay Pujols so, in a nutshell, that made financial sense at that moment. Things like that, reinforce the idea that there are just too many variables to have a straightforward answer about the real value of aging stars’ contracts.

Nevertheless, from what we have found out, we can still get the cautious conclusion that it is pretty much certain, in terms of pure on-field individual production, that these specific contracts (players in their age-31 season at the beginning of the contract) are also on the bad side of its curves, around 25% worse than the average free-agent contract.

Not all contracts to aging stars are bad, however. There have been terrific signings of 31-year-old players in the past decade, Adrián Beltré being the primary example of that. The six-year period from 2011 to 2016 of his age 31 contract was one of the best in his Hall of Fame-worthy career, averaging a 5.4 fWAR per year during that time frame (although, the following contract with Texas, on his two last years of career, this average dropped to 2.0 per year). That was an extremely good contract for Texas in terms of the on-field production Beltré achieved during it. Michael Brantley’s deal with Houston in 2019, with a 4.2 fWAR that season and 1.3 during 2020 one, is another example of a very good age 31 contract.

The thing is that for every Beltré or Brantley successful deal, there are plenty of Mark Trumbo (-0.4 WAR/Year), Ian Desmond (-0.6 WAR/Year), Alex Gordon (0.8) or Yoénis Céspedes (0.8) signings that bring down the averages as a whole to the 1.6 WAR/Year figure we found out earlier. Does that make age 31 contracts avoid-at-all-risk deals?

Sometimes, teams need to make some moves because they feel that it is their best option, and they end up assuming these risks. But, to me, signing a long deal for an older player is a very risky position, and history seems to back up that thinking.

Photos by Juan DeLeon/Icon Sportswire, Marianne O’Leary/Flickr, Rick Briggs/Flickr | Design by J.R. Caines (@JRCainesDesign on Twitter and @caines_design on Instagram).

Its not even entirely that the players are old. Those contracts are just long and ill advised from the start. There is not one day where people are like, wow, what a bargain. There is also the strange reality of the entire mess, where the people signing the guy to a terrible contract know that they won’t be around when it turns sour. I think giant contracts are PR moves more than anything else – its the only way you can justify them to start. What I find really crazy is how a team will pay one guy, but make no effort to field an entire team. I suspect that managing a franchise doesn’t have much to do with baseball. What is really interesting about the whole age thing is that if they are not breaking down, their best years often come in the danger zone. You can see it in that hit chart, in the lower 30s. I think there is also something to be said that any WAR derivative is going to be biased against aging players. Those dudes are paid to swing the bat… that doesn’t make the contracts any better, but WAR is awful and that is always worth mentioning. I think it would be interesting to look at the annual production of all large contracts.

I think I agree with 70% of your ideas, but not on the WAR stuff.

I know it is far from perfect, that’s true, but I find it to be a more than adequate tool to gauge performance.

Thanks for the comment!