This article started as a collection of quirky vignettes about the 1970 season. Like the legendary Dock Ellis LSD no-hitter and Curt Flood taking on the man and challenging the ancient reserve clause. So many odd events occurred that calendar year that on their surface appeared light and fluffy.

As these stories unfurled, however, it became apparent that quirky was the wrong approach. These stories hold a common denominator that mirrored the American experience at the time, a shared thread of frustration, empowerment, and struggling to understand themselves almost as if baseball and the country were coming of age locked arm in arm.

The golden age was over, historic milestones were finally breached, and it was time to start confronting some of the damage ignored for so long.

1969 saw the extremes of Woodstock exploring love and the ill-fated Altamont Free Festival exposing violence. They had Neil Armstrong walking on the Moon as a backdrop to the Vietnam draft lottery and mass protests. The country was beyond questioning the status quo, actively revolting against it, and baseball wasn’t inoculated against this rising social tide. For better and some for worse, this counterculture would come to define the 1970 baseball season.

These four stories are an emblem of their time. Each deserves a book to better tell them – and in some cases actually have books and documentaries – but like looking down your personal genealogy and appreciating where you came from, knowing what foundations modern baseball is built upon inks out that much more enjoyment.

Curt Flood vs The Lords of Baseball

From 1958 to 1969 Curt Flood and his family made St. Louis their home. The center fielder put up solid numbers for the club garnering three All-Star appearances, a smattering of MVP votes, and was a gold glove winner for six straight seasons. His children had roots in the local schools and he even had a burgeoning photography business in the city. Life was good.

Then he asked for a raise. Flood had a great year in ’68, leading the Cardinals to the World Series while winning his fifth gold glove and finishing fourth in the MVP standings. A raise, he believed, was not only natural but well earned. He made $72,500 that year and asked to make $90,000 for the ’69 season. A high salary but nowhere near league top, it simply met his on-field contributions.

The Cardinals balked at the request. The owner of the team came down a few months later in spring training to lecture the players in a direct call-out of Flood’s audacity.

“Too many fans are saying our players are getting fat, that they only think of money, and less of the game itself. The fans will be looking at you this year more critically than ever before to watch how you perform and see whether you really are giving everything you have.”

The ’69 season was played with that ominous dark cloud looming over Flood. The news leaked that the center fielder was looking for a raise, that he was an undesirable willing to throw the good of the team under the bus for his own personal gain. The common thought among the public (and management) was that Flood is already making significantly more than the average American, so what does he have to complain about? Being traded and unable to sign where you want is just the way baseball is.

Flood finished 1969 with a pedestrian season for his standards, and midway through the season had his captaincy of the team stripped. Then, perhaps predictably for challenging the status quo, he was traded to Philadelphia as the off-season began.

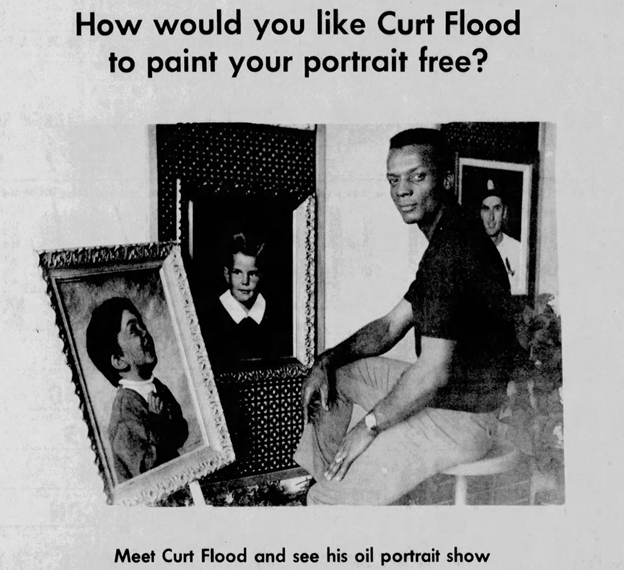

Ad from the “Neighborhood News” St. Louis Newspaper from July, 1969

Like every other player since 1887, Flood’s contract was automatically renewed each year by the team that owned his rights. It was that tried-and-true reserve clause. In no way were players allowed to sign with other teams if their current club couldn’t meet the player’s salary demands. Negotiations (if you could call it that) were often blackmail with no other choice in where to go. The team owned the player in perpetuity, if a player made a comeback at the age of 55 their original team would still hold rights. ‘Till death do they part.

The clubs owned the player and their destiny until the team simply didn’t want them anymore. Not only did that remove player agency from living and playing where they want, this reserve clause also allowed teams to severely hamper salaries for players. The minimum salary in 1970, for example, was $12,000 (slightly above the median income of families in the United States at the time) and the average hovered at $29,000.

When Curt Flood was traded after being in the league for 12 years, he had no say in where he and his family would live and had zero leverage in salary negotiation in this new place he didn’t want to be. Now, Flood was far from the first player who was subjected to this critically unfair treatment and wouldn’t be the last. But Flood did something no other player had done. He challenged the trade.

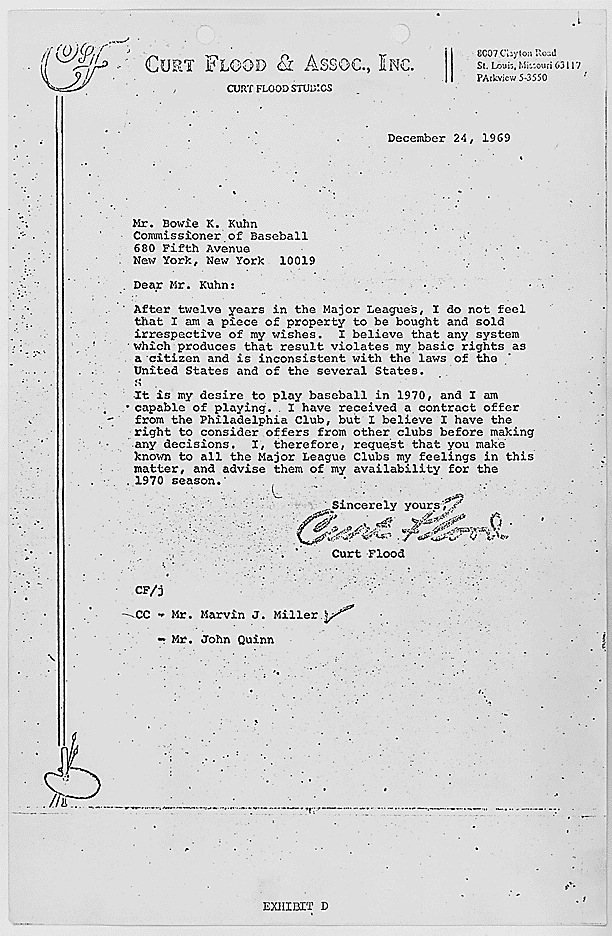

In a letter to MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Flood wrote,

“After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. … I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.”

Predictably the owners circled the wagons, and 1970 would be played without the five-time gold glove winner as he took baseball all the way to the Supreme Court in Flood vs Kuhn.

Players around the league weren’t unanimously behind Flood’s efforts despite this attempt to better their circumstances. In fact, it was reported that maybe just 10% of the players were behind him. Momentous voices shared their displeasure. Ted Williams told people privately Flood was finished, Joe DiMaggio and Carl Yastrzemski were both against him, and Joe Garagiola went so far as to defend the reserve clause in the Supreme Court saying, “To me, this is the best system so far and I haven’t heard anyone come up with a better one,”

Flood went on to lose the case, 5-3 ruling in favor of Major League Baseball. It didn’t help that Flood’s own lawyer told the Court that his argument “was the worst argument I’ve ever made in my life.”

He came back to baseball for the 1971 season but came back to abuse. He routinely found death threats in notes left on his car, fans threw beer at him, and someone even left a black wreath on his locker. One of Curt’s teammates described him at the time as “…the saddest person he had ever met or seen. It was awful.” He played just 13 games before retiring.

Any player rarely has as big of an impact on the game that Curt Flood did. As a direct result of his sacrifice – and it was a sacrifice – free agency finally took hold in 1976 with the nullification of the reserve clause. Players were finally paid a salary more reflective of the value they brought to the game.

Denny McLain and the Syrian Mafia

Denny McLain was fresh off back-to-back Cy Young Awards in 1970, even taking home the MVP in ’68 when he won a historic 31 games. That year he led the Tigers to the World Series and on paper was a superstar of the league. He worked fast on the mound, daring batters to hit the same pitch twice, offering them the chance to call their own location, and wore his cap down low like a predator hunting his prey.

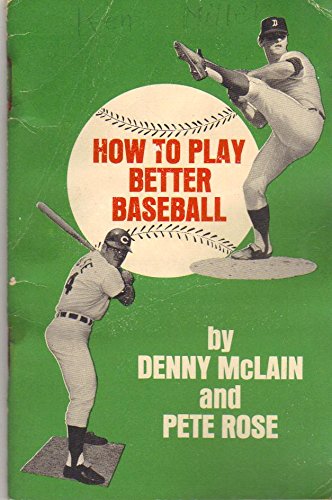

Off the field, his face was constantly on television, appearing on talk shows, radio, playing the organ and singing to audiences, even writing a book with Pete Rose. Like Rose, McLain was notorious in the clubhouse as a gambler and was known for easy money on the poor bets he made – earning himself the nickname Dolphin because he was a fish at card games. He burned with reckless abandon on and off the field.

“How to Play Better Baseball” Published January 1, 1969 by Frank Scott Associates

After taking home his second Cy Young in as many years and living loose and carefree, the 25-year-old felt the weight of reality crunch him. On February 23, 1970 Sports Illustrated published from the “Neighborhood News” St. Louis Newspapered a piece called “The Downfall of a Hero”. The piece detailed Denny McLain’s involvement with a bookie named Jigs Hazell and the Syrian mob.

The report revealed how a foot injury in 1967, likely costing the Tigers the pennant, wasn’t the result of a stubbed toe or chasing raccoons as McLain said, but instead was caused when a 6′, 210 lb mob enforcer named Tony Giacalone dislocated two of McLain’s toes over failure to pay a $46,600 bet. It was also revealed that Giacalone had bet that the Angels would win the final game of the 1967 season, a game where McLain pitched and only lasted 2.2 innings.

The article ignited outrage across baseball, though McLain denied nearly everything. Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn revealed, “There [was] no indication that [McLain’s] activities in any way involve the player or outcome of baseball games” but still acted swiftly, suspending him “from all organized baseball activities.”

When the pitcher did come back in the middle of 1970, he made poor decisions that may have been brushed aside if he were a clean superstar. He earned a seven-day suspension when he poured ice water on two journalists and was again suspended, this time for the remainder of the season when he took a gun aboard a team flight.

In 1968 he won 31 games, and in the 1971 season, he lost 22. He was out of baseball completely just four years after winning the MVP and months after being considered one of the best players in the league.

He went on to make a living in a variety of ways, like making $160,000 for smuggling a criminal out of the country, owning a bar, hustling golf, promoting a minor league hockey team, and a variety of other hustles. The life of one hustle to the next caught up to him, and in 1984 he was convicted of racketeering, embezzlement, and cocaine trafficking. McLain served five years out of a 30-year sentence. When he got out, the former pitcher was indicted on charges of embezzlement, money laundering, mail fraud, and conspiracy when he and an associate bought a meatpacking plant. He served another seven years in prison.

There’s no atonement story for Denny McLain. He’s a figure beloved for his historic if brief, success on the mound but whose off-the-field decisions cut short his hall of fame trajectory.

Dock Ellis’s Redemption

You know the story. The young Pittsburgh Pirates flamethrower allegedly tossed a no-hitter while throwing the ball down a technicolor rainbow road of LSD fog. It’s a legendary baseball story that scratches the itch of the baseball mythology while blissfully ignorant of far deeper issues. Not only did Dock Ellis throw a no-hitter on LSD, Dock Ellis by his own admission never pitched a game sober.

The Pirates were on a road trip through California to play the Giants, Padres, and Dodgers. Dock Ellis, 25 years old at the time, was still finding his footing in the early season. His earned run average was well above league average and had only lasted five innings his previous outing, but Ellis’s season dramatically turned around on June 12. Well, starting on June 10. Having grown up in Los Angeles, Ellis asked the team if he could visit friends in the city while the team went to San Diego. He wasn’t scheduled to pitch for a few days so the Pirates agreed.

The young player timed his drive just right so that when he took LSD on the road, it would hit right as he arrived in LA. That’s when the blur began. Lost in the haze of vodka, LSD, marijuana, and friends.

He woke up at noon, took another dose of acid, and fell back asleep.

At 2:00 pm, a time lost to Ellis, a friend woke him up saying, “Dock, you have to pitch today in San Diego!” He said he didn’t pitch until Friday. “It is Friday!”

The friends banded together to get Ellis on a 3:00 pm flight, and he arrived just 90 minutes before the first pitch still in a haze. He later said the ball felt like a heavy beach ball at first, then switched to a small golf ball, and he threw the pitches down a rainbow road. “I started having a crazy idea in the fourth inning,” Ellis later said, “that Richard Nixon was the home plate umpire, and once I thought I was pitching a baseball to Jimi Hendrix, who to me was holding a guitar and swinging it over the plate”

Eight walks and nine innings later, the first and only LSD assisted no-hitter was complete. That story is ingrained in baseball’s culture by now. But Ellis’s story was just beginning. He continued to have a solid year, then became an All-Star in 1971 pitching against Vida Blue, marking the first time – and still only time – two black pitchers started the game. That was a monumental moment for Ellis, having fought for the two best pitchers to start the game saying, “Ain’t no way they gonna start two brothers against each other in the All-Star Game … when it comes to black players, baseball is backwards and everyone knows it.” He pitched effectively the rest of his Pirates career, then bounced around the league as arm troubles set in and he retired in ’79.

2,128 innings pitched in his career, and for none of them, he claimed, was he sober. His first drink came as a young kid when he drank his grandfather’s vodka thinking it was his water. Then Dock and his friend would steal bottles of wine from stores, mixing them with Kool-Aid, and drinking them in a makeshift cardboard fort. He continued drinking growing up, then finding a variety of drugs like greenies that were abundant in baseball and Dexamyl to get evened out. There was also cocaine, heroin, and pills he called “red devils”. Looking back, he said, he couldn’t remember most of 1969 and 1970.

Dock checked into rehab for alcohol and drug addiction the year his playing career came to an end. He stayed at the clinic in Arizona for a month and a half, two weeks longer than insurance allowed because he was horrified of relapsing.

He joined support groups back home in Los Angeles, then began studying psychology at Irvine and became a substance abuse counselor, dedicating his life to helping others trying to claw out of addiction. He would continue to help young professionals, prisoners, folks unable to afford treatment, and anyone else along his path. Dock even tried to head up Major League Baseball’s drug treatment problem in the early 90s – though the league held contempt for Dock due to his boisterous and often confrontational demeanor, never afraid to call out injustices.

Dock Ellis’s LSD no-hitter belongs in the inner-circle lore of the game, absolutely, but his actions after his playing career had a far deeper impact in his life and in others.

Tony Horton

Major League Baseball hid Tony Horton’s story for 27 years, brushing him under the rug with other hard realities they refused to confront. That ended when Bill Madden published an article in 1997 for the New York Daily News.

Tony Horton, as teammate Graig Nettles succinctly put it, “was a stud.” He was called up to the Red Sox at the young age of nineteen and became a mainstay for the Boston club. Ted Williams watched Horton swinging in the cage his rookie season and said, “This kid is a natural. You don’t fool with a swing like that.” A former three-sport star who turned down basketball scholarships to UCLA and USC, the Red Sox signed the 6’3’’, 210-pound player right out of high school. He had all the tools in the world. But Horton was wired for perfection. He never relaxed. Always gritting his teeth. He could never quite reach the expectations he set for himself.

The Red Sox traded Horton to Cleveland in 1967 and he started tasting that potential. He became an above-average hitter immediately, even leading his team in home runs during the infamous year of the pitcher. After three years and at only 25 years old, he appeared on the MVP ballot for the first time in 1970 – which would prove to be his last season.

Horton asked Cleveland for a raise prior to the 1970 season, and with the reserve clause still alive and well, the ball club refused to even entertain the offer saying that if Horton doesn’t play for his current salary, the team will just have another player helm first base. Horton was forced to sign for $19,000 less than what he asked for. He immediately put pressure on himself to play so well that the team would be required to pay the salary he wanted.

Of course, word got out that Horton had asked for a substantial raise. Once again the fans and media believed being paid to play a game was rewarding enough, and Horton began to hear the boos. His manager Alvin Dark would later say, “[Horton] gave everything he had and just couldn’t understand why they were booing him.”

He would hit below his career averages through the season as he pressed in on himself.

In a late June game, Horton faced down Yankee Steve Hamilton, famous for his cartoonish eephus pitch that lackadaisically bounded into the air, catching batters expecting a fastball off guard often with embarrassing results. The first eephus Horton barely fouled off. On the second long looper, Horton meekly popped up to the catcher. He dropped to his hand and knees and crawled back to the dugout in mock embarrassment. The dugouts got a kick out of it.

It wasn’t funny to Tony.

The season wore on and his struggles continued. He folded more inwards even when he began to find his swing again. Horton would walk around dazed in the clubhouse with shower slippers, and once stood at first base once the stadium cleared out not realizing the game had ended. The signs were there, blaring out for help, only in 1970, there was no one to read them.

The immense pressure he put himself under came to a head-on on August 28 when it became apparent to teammates and management that something was wrong, but they simply didn’t know how to help. They pulled him from the second game of a doubleheader and sent him home, back to the motel where he was living.

The difficult details that followed are described in Madden’s article. Horton was found in his car before sunrise and was rushed to the hospital with self-inflicted wounds.

The doctors patched him up but strongly recommended he stay away from baseball. It was obvious to them that the burden of stress and anxiety would inevitably lead to another breakdown, only the next time may not end in a hospital. Tony Horton would never play another game of baseball despite being listed on the MVP ballot for the first time in 1970. He was just 25 years old when he stepped away.

The suicide attempt was never reported in the press, nor did Cleveland offer an explanation beyond statements of recovery from a nervous breakdown. Horton shunned all contact from the baseball world, never being heard by teammates or managers again. Journalists have attempted to reach out to Tony and talk about his playing days, but he’s requested not to be contacted.

Baseball

The 1970 season brought growing pains to Major League Baseball. They were painful at the moment and remain painful in retrospect, but the game, and most importantly the people who live in it, are better off today because of those pains. Players and other people in the game can now better control their own destiny through not only free agency, but the ability to seek counseling, and bringing topics once layered in stigma to the front of the conversation.

Baseball and our culture at large still have progress to make, and that progress begins with people like Dock Ellis and Curt Flood, and cautionary tales to learn from like Tony Horton and Denny McLain.

Photos by Michelle McEwen/Unsplash and Salam Habash/Unsplash | Adapted by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)

I love this site, I’ve come here nearly every day from Feb-Nov for years now, and this is probably the most important article I’ve ever read on the site. Thanks for compiling these stories, Brandon.

Next on the docket should be a genuine and detailed look into the life of minor leaguers that didn’t get huge signing bonuses.

PS – Obviously, they should be unnamed in said article

What do Syrians have to do with the Mob?

Awesome job.