If you followed baseball at all in 2020, I don’t need to tell you who Randy Arozarena is. He set the baseball world on fire with an otherworldly 2020 postseason performance, setting the bar awfully high for himself. And by many marks, he delivered during his first full season in 2021. He finished with exactly 20 homers and 20 steals, posted an OPS north of .800, and was crowned the AL Rookie of the Year—all while doing stuff like this to keep us entertained:

https://gfycat.com/veneratedmadicelandgull

2022, however, hasn’t told the same story:

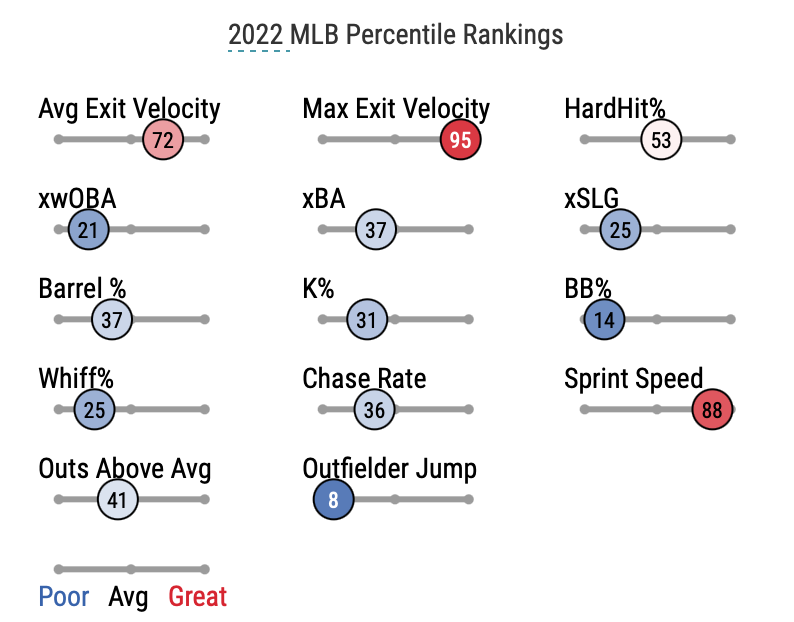

This isn’t what you’d expect from the guy who was channeling Barry Bonds against some of the best talent in the game, and it certainly isn’t what fantasy managers wanted from someone who was going as high as the fifth round in drafts. The expected stats say he’s earned exactly what he’s put up. To put it simply, he’s not living up to his potential—but there is still a path forward for him to do so.

Failure To Launch

Two numbers speak to a big reason Randy is so tantalizing as a player: 95th-percentile max exit velocity and 88th-percentile sprint speed. Power/speed is an uncommon combination in today’s game, so when a player flashes both, it puts people on notice.

However, raw strength doesn’t mean a whole lot if you’re hitting the baseball straight into the ground. According to Baseball Savant’s leaderboards, out of 161 qualified batters this season, Randy has the 13th-highest ground ball rate. He also has the 4th-highest rate of “topped” batted balls—such batted balls almost always have a negative launch angle and rarely turn into something other than a groundout. It speaks to a hitter who’s not making the contact he should be making if he wants to take advantage of his power.

Randy’s batted ball profile already looked like a warning sign last year, and all of these metrics have gone in the wrong direction. Altogether, Randy’s profile is an interesting case study of the limitations of Max EV and what it can tell us about a batter’s power. Having the ability to knock the stuffing out of the ball is well and good, but it needs to be paired with an ability to square the ball up well to start to mean anything.

It is worth noting that Randy’s speed helps buoy his average a little bit—he’s tied for second among qualified hitters with 13 infield hits. But hustling out a couple of grounders here and there isn’t the threshold between okay and superstar. Besides, we want to see Randy make the most of his skills by tapping into that power potential like we know he can.

A Twin Spirit?

When thinking about how Randy might be able to turn a corner and become the hitter we imagined he might be, there is another outfielder who could serve as a model, someone who was looking like a burnt-out prospect before he took baseball by storm: Byron Buxton.

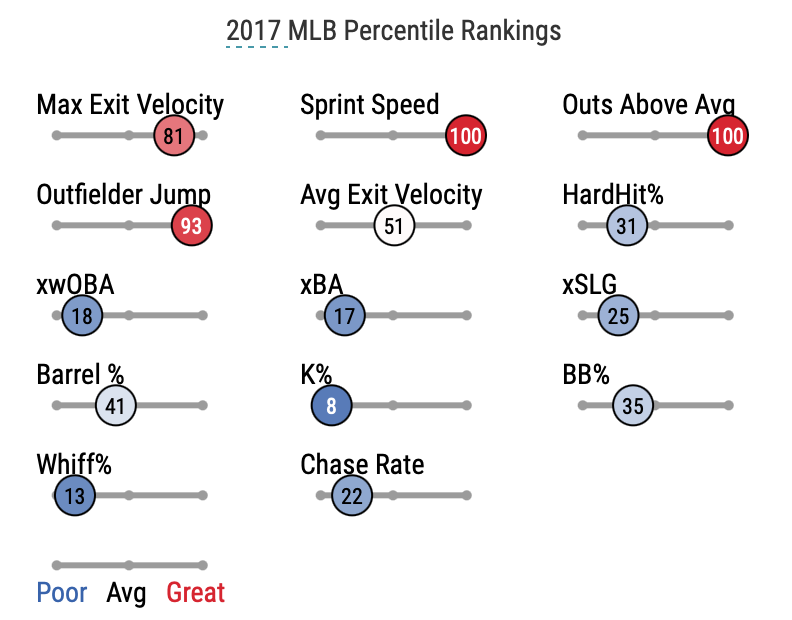

True, a big thing holding Buxton back from coming into his own was the injury bug. But let’s take a look back at Buxton’s 2017 season for a little comparison and see if we can find anything that Randy can learn from. Why 2017? Well, part of the reason is that it’s a big enough sample size to be interesting—Buxton played in 140 games that season but didn’t play in more than 87 from 2018-2020. But more importantly, 2017 is a good starting point because Buxton’s profile then and Randy’s profile now are eerily similar:

Save for Buxton (left) vastly outperforming Randy on the defensive side of things, there’s clearly quite a bit in common here: two guys with Statcast profiles hinting at great raw skills but lacking the on-field results to back it up.

2021 was Buxton’s breakout year, but the pieces started falling into place before then. Moving forward from 2017: he only played in 28 games in ’18, so there’s not much we can learn there. He only managed a little more than half a season in ’19, but we started to see some changes. The first was that he stopped hitting the ball into the ground so much.

The second was that he cut back on his strikeouts. With those changes, he worked on dialing in his new skillset. Come 2021, Buxton backed up his strikeout gains by chasing at a career-low rate, made harder contact than ever, and launched baseballs all over the place.

With all this in mind, let’s turn our attention back to Randy. The batted ball quality, as we’ve discussed, is wanting. Randy needs to start lifting the ball in the air more for the power results to come through. His plate discipline this year has been a mixed bag compared to last year:

The strikeout rate is down a few ticks, which is a good thing. It’s tied to a drop in his whiff rate, which is also something we like to see. However, the chase rate is way up—which is out of character for him. Coming up as a prospect, one of Randy’s calling cards was his pitch recognition skills and the ability to lay off close pitches. It’s what helped him get away with having a higher whiff rate.

Last year, he was in the 68th percentile for chase rate; this year, he is in the 36th percentile, and his walk rate has been cut nearly in half. While it’s a good thing to make more contact and strike out less, Randy is expanding the zone too much. He looks a lot less like that deadly hitter we saw glimpses of, the one who would wait for the perfect pitch and pounce on it.

Also, on the subject of things that were once strengths and are becoming weaknesses: Randy is having significantly less success against fastballs this year. He’s managed only a measly .310 wOBA against them, over 100 points lower than how he fared against heaters last season. You know what Buxton started crushing when he broke out in ’21? Yup, fastballs—to the tune of a .464 wOBA. Randy needs to get that swagger back against heaters to regain feared-hitter status.

There is one more factor that should be noted if we’re going to talk about this Randy/Buxton comp. In 2017, Buxton was only 24 and had a lot of baseball ahead of him. His 2021 breakout came in his age-27 season, the same age Randy is now. This is the age in a player’s career when they would want to be entering their prime, not still figuring things out. It’s not like the Grim Reaper is coming for Randy anytime soon, but he’s not a kid anymore. It’s an interesting position to be in: his MLB career hasn’t been that long, but he’s not quite of an age where you would pin him as a player still developing.

Looking Ahead

There is a path for Randy to re-emerge as the terror we saw during the 2020 playoffs—Byron Buxton is evidence of that. But it’s going to take an overhaul of the contact he makes, a tightening up of his plate discipline, and far better outcomes against heaters. When Randy is playing at his best, the game of baseball is better for it. He has more than enough talent to break out for real, but there’s a lot that needs to go right for that to happen.

Photo by: Randy Litzinger/Icon Sportswire. Adapted by Matt Fletcher (@little.gnt on Instagram)

Fwiw, if you throw out Randy’s horrendous April (.507 OPS with a 66% GB rate and 29.6% K rate), the numbers look a lot better, albeit not amazing (.275/.332/.446 with 7 HR, 14 SB and a 22.9% K rate), really pretty similar to his 2021 statline with more SBs. Maybe this is just who he is?