It’s hard to treat an injury when you don’t know what you’re looking for. When pitchers are dealing with pain in their throwing elbow, an MRI can usually help doctors understand if pain is related to a UCL tear and if Tommy John Surgery is required. When it comes to concussions, though, there’s not a surefire way to assess the severity of the trauma and map out a timetable for recovery.

When you think of concussions in sports, your mind might jump to contact sports such as boxing or football or hockey. You might remember the movie Concussion, headlined by Will Smith (the actor, not the catcher, or the reliever!), that told the story of the forensic pathologist who discovered the first case of CTE. You’ve probably also heard about the NFL and NHL reaching settlements with groups of former players in concussion lawsuits. Through a brain donation program, a group of researchers set out to study the brains of deceased American football players. Their findings were stunning: 110 of 111 brains from the NFL sample showed evidence of the degenerative brain disease CTE.

It’s undeniable that sports have come a long way with regard to concussions. We don’t describe head trauma for boxers as punch drunk syndrome anymore or allow football players to remain in the game when they got their bell rung. Major League Baseball has implemented a rule to curb home plate collisions and is slowly distancing themselves from headhunting being an acceptable way to enforce the game’s unwritten rules. They even implemented the 7-day injured list specifically for concussions.

We’re headed in the right direction, but is this enough? To date, there has only been one known case of CTE in a former MLB player. Ryan Freel was a utilityman who spent most of his career with the Cincinnati Reds. He suffered multiple concussions, including those that came from a collision with a teammate and getting hit in the head by a pick-off throw. Freel died by suicide in 2012 and, through his family’s donation of his brain, was later diagnosed with CTE.

But only focusing on CTE is part of the problem. Catchers take countless foul tips to the face mask, outfielders crash into walls at full speed trying to make a catch, and pitchers get hit with line drives before they’re able to finish their delivery. Individually, these foul tips, collisions, and comebackers may not induce the buildup of tau proteins or shrinkage of brain mass that are common in cases of CTE, but they do lasting damage. Each injury leaves a player more vulnerable to future harm. If baseball isn’t going to make the necessary changes for their players’ health, maybe they’ll pay more attention when concussions are shown to negatively impact a player’s performance.

Francisco Cervelli was in good hands as a young, backup catcher with the Yankees. He only played in a handful of games in the last two weeks of the New York Yankees’ 2008 season, so there’s not much to glean there. But, from his debut with the Yankees until 2014, Cervelli was under the tutelage of two stellar backstops: José Molina and Russell Martin. Jorge Posada was of course the team’s starting catcher and has secured a spot among the Yankee greats, but he was notoriously bad defensively. (This isn’t Yankees slander: Per FanGraphs, Posada has the second-worst DRS among catchers who have logged at least 5,000 innings behind the plate.) Thus, because this is a defensive-focused look at Cervelli’s career, Molina and Martin will be a greater comparative focus than Posada.

A quote from my favorite book, Chad Harbach’s novel The Art of Fielding, goes as follows:

“Baseball was an art, but to excel at it you had to become a machine. It didn’t matter how beautifully you performed sometimes, what you did on your best day, how many spectacular plays you made. You weren’t a painter or a writer – you didn’t work in private and discard your mistakes, and it wasn’t just your masterpieces that counted. What mattered, as for any machine, was repeatability. Moments of inspiration were nothing compared to elimination of error.”

Pitch framing has long been a vastly overlooked part of the game and, although its value has received more recognition lately, it’s not likely that catchers will get their own version of the day’s nastiest pitches. From pitch to pitch, it can be difficult to envision the immense potential that each offering’s movement has. For catchers, this might be by design. The more fluid the motion of framing a pitch, the more natural the start-to-stop is, the more likely the borderline ball becomes a borderline strike. When done consistently, the potential the catcher has to impact the game is monumental. But, you might not be conditioned to see it…moments of inspiration were nothing compared to elimination of error.

Consistency can come naturally as battery-mates build chemistry overtime and pitching staffs begin to assemble from season to season. Without a strong foundation of sound fundamentals, however, a catcher is at risk of falling victim to bad habits which can be reinforced over time.

In a 2013 article for Grantland, Ben Lindbergh highlights the differences between two very similar pitches that were caught by two catchers positioned on the opposite ends of the defensive spectrum. Where José Molina zigged, Ryan Doumit zagged. Lindbergh noted the following differences: The former catcher sets up outside and catches the pitch within the center of his body, presents a low and stable target, keeps his head steady, and moves his glove subtly. The latter catcher sets up more centered and reaches across his body to catch the pitch, presents a higher and more mobile target, jerks his head down, and moves his glove dramatically. These very similar pitches had drastically different outcomes. The pitch Molina caught was called a strike and the pitch Doumit caught was called a ball.

Fortunately, repetition can help rework bad habits into good ones. A catcher that is bad at pitch framing can become better by making mechanical adjustments that may generate more called strikes on borderline pitches. This can be done through the tweaking of where the catcher positions his body, sets his glove, and by becoming more fluid and smooth with his movements behind the plate.

Paul Brendel’s 2020 article here at Pitcher List explored catcher defense and its relation to pitcher’s production while also considering variables such as age factors and year-to-year consistency. He also looked at FanGraphs’ framing metric (FRM) among the league’s catchers who caught 500 innings in each of three consecutive seasons from 2017-2019. Outside of a few outliers among the group of 19, framing remained relatively consistent from year-to-year among both age groups of young and old catchers. Paul concluded that, aside from the few outliers, “the catchers generally stay within the top/middle/bottom of the pack.”

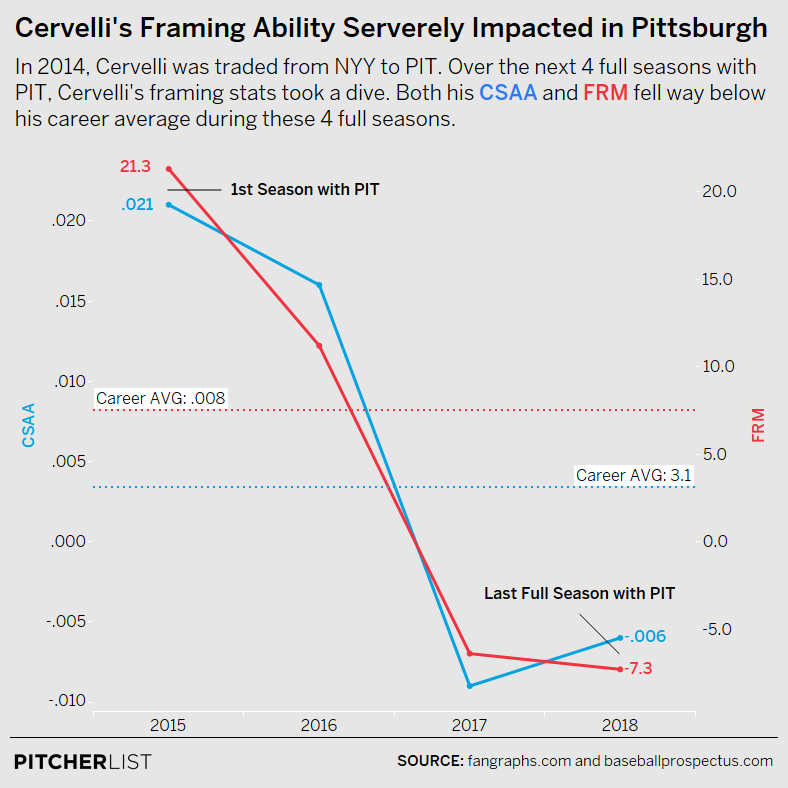

So, this takes me back to Cervelli. How did he, almost suddenly, go from one of the best pitch framers in baseball to one of the worst? We’ll take a look at two defensive metrics for catchers: CSAA and FRM. These two statistics are closely related and FRM, specifically, is used here because the aforementioned Going Deep article explored the stability of this metric.

CSAA stands for Called Strikes Above Average and can be found at Baseball Prospectus. The gist of CSAA is that an average catcher will not make a ball look like a strike, or a strike look like a ball. Because the average catcher will not impact the call, they have a CSAA of 0.000. So, a catcher with a positive CSAA is able to receive pitches out of the strike zone in a way that makes them look like a strike. A catcher with a negative CSAA receives pitches that are normally strikes in a way that brings them outside of the strike zone and called a ball. For reference, a good framing catcher may have a CSAA of 0.010 and a bad framing catcher may have a CSAA of -0.010. The higher the CSAA, the better framer.

FRM stands for catcher framing and can be found at FanGraphs. FRM shows us the extra strikes a catcher received in terms of runs, which may be easier to visualize than strikes with CSAA. The idea remains the same: a catcher who receives pitches well enough to get extra strikes will save their team more runs over the course of a season; a catcher who receives pitches poorly and loses strikes will cost their team runs over the course of a season. For reference, a good framing catcher may save his team 4-6 runs per season and a bad framing catcher may cost his team 4-6 runs per season based on pitch framing alone. It’s important to note that one site may calculate runs slightly different than another site, but the trend is generally the same.

Cervelli’s playing time was sparse with the Yankees. A broken wrist, broken foot, and two concussion piled up between 2008-2011, leaving the little playing time he saw as Posada’s backup to dwindle even further. When he was finally healthy in 2012, this opportunity had dissipated and Cervelli was relegated to Triple-A for all but three games. Still, he kept working. In an article for The Players’ Tribune that Cervelli penned in 2016, he admits that the nearly-17 year old the Yankees signed in 2003 had never caught before. He learned the position in the Yankees organization and, in the playing time he did get, the results were promising. By 2009-2010, Cervelli was getting 0.006 CSAA. He raised that number to 0.023 in 2011 and kept the same rate when he returned to the big leagues in 2013. After another consistent year in 2014, Cervelli was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates and leapt at the opportunity to be their starting catcher.

Data Visualization by @Kollauf on Twitter

Cervelli’s first two years in Pittsburgh were astounding. But arguably even more astounding is the divide between 2015-2016 and 2017-2018. Cervelli was a top 10 framing catcher in both 2015 and 2016. He saved 21.3 runs by framing pitches in 2015, which was second-best among all catchers in baseball. He was slightly less effective in 2016, but his 11.2 FRM was still eighth best in the league. This two year stretch was also the healthiest he had been in his career. He remained injury free all of 2015 and missed just over a month in 2016 due to a broken hand. His first 231 games as a Pirate were a success.

Right here, however, is when things begin to take a turn for the worst. There’s a scary moment in a game during the 2017 season in which Cervelli is crouched behind the plate in a tie game in the ninth inning. With two strikes and two outs, the Baltimore Orioles were down to their last strike if they want a chance to keep the game from going to extra innings. Tony Watson delivered the pitch, Caleb Joseph took a hack, and in an instant, a foul ball crashes into Cervelli’s mask and he falls back into the arms of the home plate umpire.

This foul tip would start the cycle to and from the injured list for Cervelli over the rest of his career. The last two full seasons Cervelli spent in Pittsburgh, he landed on the injured list four times with a concussion or post-concussion syndrome. In 2017, he was on the injured list for 7 days, was activated and appeared in 4 games, then returned to the injured list for 13 days. In 2018, he sustained another concussion which sent him to the injured list for 16 days, was activated and appeared in 5 games, then returned to the injured list for 12 days.

When you consider what’s going on inside of the brain of someone dealing with a concussion, it’s easy to see how devastating they can be. You might have heard the jello analogy: your brain is protected by your skull like Jell-O in a jar. A collision or sudden jolt to the jar will shake the contents violently into the sides of the jar, possibly separating a few pieces of Jell-O. A concussion is similar: The sudden movement and force shakes your brain and neurons can stretch or break apart from each other. Once these neural pathways are disrupted, communication within the brain becomes much more difficult. Basic tasks that were once completed automatically now require conscious effort, so it’s understandable that normal functioning would be much more difficult.

A serious problem arises when the individual who has sustained a concussion returns to normal activities before the brain is fully recovered. Further, a second concussion sustained within this window of recovery can be life-threatening. This isn’t meant to induce fear or point fingers. My hope is that we begin to pause and reconsider the way we react when a player is removed from a game or misses time with a head injury. It shouldn’t come down to how many strikes a catcher loses for his pitcher, how many games the fans are forced to root for the back-up, or how many points a player’s strikeouts dock fantasy teams. There’s no such thing as “suck it up” or “tough it out” when it comes to head trauma.

In talking with a treatment specialist who uses neurofeedback to treat individuals with traumatic brain injuries, it became clear that disregarding Cervelli’s extensive concussion history when assessing the severe decline he experienced behind the plate would be irresponsible. Head trauma can weigh on a player’s ability to concentrate, balance, and react. Headaches and sensitivity to a loud or busy environment are also common. The treatment specialist noted how demanding playing a sport at such a high level is normally. To do his job, a catcher must exude calm. Tune out the crowd, connect with the pitcher, consider the game plan, watch the runner at first, receive the ball. Then, do it all over again. This is nearly impossible to do, even at an average level, with debilitating symptoms.

Before the 2017 season, Pirates pitchers applauded Cervelli’s consistency behind the plate. Jameson Taillon told Adam Berry of MLB.com that Cervelli’s “sharp eyes and strong wrists” help make him the successful catcher he is. Steven Brault credited his “low, ‘spider’-like setup” and the way he reacts and catches pitches out front to make them appear closer to the strike zone. Now, did Cervelli’s wrists all of a sudden become weaker from the time Taillon made those comments to when the season started just a few months later? No, probably not. Did Cervelli begin setting up differently since Brault made that observation? Video from season to season says no. The other noteworthy skills both Taillon and Brault mentioned — hand-eye coordination and reaction time — would be things that a concussion could impact. The specialist I talked to agreed.

After the tumultuous seasons he endured in 2017 and 2018, Cervelli was healthy and started 22 of the Pirates’ first 27 games in 2019. Then a broken bat caught Cervelli behind the plate in May and he would return to the injured list with another concussion, this time for 88 days. After being released and signing with Atlanta for the rest of 2019, Cervelli came to Miami for the 2020 season hoping to impact the Marlins’ young pitchers with his veteran presence. A foul tip would wind up ending his season and career.

When he announced his retirement in a post on his Instagram page, Cervelli ended the caption with the following: This game will always be my greatest love, because… well, THAT’S AMORE!”

I watched that final game live and there was one thing that stuck with me, as both a fan and a former injury-prone athlete: the moment he knew something wasn’t quite right and he’d have to come out of the game, Cervelli apologized to manager Don Mattingly. Then reading his post on Instagram, I was reminded that no one is more disappointed with a setback or injury than the player who just had the game taken away from them.

Looking back to the quote from my favorite book, I may have missed something all along, the idea that “what mattered, as for any machine, was repeatability. Moments of inspiration were nothing compared to elimination of error.” The athletes we cheer for, and even root against, are not machines. Elimination of error, in theory, is great for us as fantasy owners. But it’s the moments of inspiration that bring joy to our baseball fandom, and those are impossible when a player is not physically and mentally healthy.

And I think Mattingly got that. He would later relay to the media that the organization understood the dangers multiple concussions can bring to athletes later in life. He told Cervelli that he wants his player to be healthy, but he also wants him “to have a great life after baseball.”

We don’t always see managers or coaches put the person before the player. Mattingly did, and I hope his words and actions will help others do the same. That’s amore!

Photo by Scott W. Grau/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)