Making it all the way back from one Tommy John surgery is an accomplishment, much less two. Or with a cancer diagnosis in between them.

But that’s exactly what Jameson Taillon appears to be on the verge of doing. We’ll all be happy to see him back on a big-league mound come April, but it’s been a frustrating now decade-long career for the right-hander from suburban Houston, who was taken by the Pirates with the second overall pick in the June 2010 draft.

The players selected directly before and after him are each entering the third year of contracts totalling more than $600 million, but thanks to those medical issues, Taillon is making just his second trip through arbitration, and won’t hit free agency until after the 2022 season. In spite of the hard luck, he did at the very least show himself to be a top-of-the-rotation caliber pitcher before going under the knife again. Let’s look at where Taillon left off as he prepares for his second comeback this spring:

| Year | W-L | IP | ERA | FIP/xFIP/SIERA | BB% | K% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 5-4 | 104 | 3.38 | 3.71/3.43/3.61 | 4.1 | 20.3 |

| 2017 | 8-7 | 133.2 | 4.44 | 3.48/3.89/4.24 | 7.8 | 21.3 |

| 2018 | 14-10 | 191 | 3.20 | 3.46/3.58/3.77 | 5.9 | 22.8 |

| 2019 | 2-3 | 37.1 | 4.10 | 3.80/4.06/4.38 | 5.1 | 19 |

The timing couldn’t have been much rougher for his second surgery, but with the pandemic mucking up the timeline for just about everyone, he’s not as far removed from success as it might seem. Still, he now faces the challenge of just returning to those 2018 levels of success, a much tougher task than building off them as a baseline. Fortunately, he’s been kind enough to document some of his rehab work for us, and show that he has every intention of picking up where he left off:

Love getting to do a “normal” progression into the season. Been a while! The build up continues ? (Sorry for the dumpy video quality) pic.twitter.com/DbZYuWwbqX

— Jameson Taillon (@JTaillon50) January 9, 2021

For some context, here’s Taillon throwing a fastball from the stretch in 2019. He’s clearly not working at 100% speed in his recent video, but the differences are still noticeable:

(Source: Baseball Savant)

Do I spy a new and an improved arm spiral? I think we do! A revamped arm path is particularly exciting for someone like Taillon, whose long mechanics previously contributed to his arm health woes, as he told Nick Pollack on a Talking Pitching podcast this past spring. And it’s not just his arm, either:

One of these throwing motions used to feel really natural (which is scary), and one currently has become really natural through lots of intentional/focused work. Crazy to take a step back and look at every once in a while! pic.twitter.com/HelH6zFQoc

— Jameson Taillon (@JTaillon50) November 28, 2020

Foot strike Nov. 2018 vs Foot Strike Nov 2020. Looks a little tiny bit different ? pic.twitter.com/pNeWG4CM46

— Jameson Taillon (@JTaillon50) November 5, 2020

That’s about as good of a side-by-side as we’ll ever get, and while the new arm action is what stuck out first to me, beyond that, his lower half looks a lot more in sync.

In the picture on the bottom left, look at that chunk of knee you see sticking out a bit, and how it’s disappeared in the more recent frame. Now move back to the 2018 side of the top tweet, and you can see clearly how his shin, knee, and presumably foot, are pointing somewhere off between the plate and the third-base dugout. His hips are closed and locked into place, his weight is everywhere, and the injury struggles start to make a little more sense. More recently, everything is more linear, his hips are open and flexible, and his trunk is in a position to rotate tighter with a cleaner arm spiral.

All in all, it looks pretty good. Now we have to wait and see what he’s going to do with it.

There’s plenty to talk about when it comes to Taillon’s stuff and approach, so let’s go pitch by pitch. I don’t have too much to add here about his curveball—not without careening over 3000 words, at least. It’s been a constant for Taillon dating back to his high school, days, and it’s more or less always graded out as a plus pitch. It usually looks the part:

It doesn’t draw quite as many of those as you’d expect, running a below-average 13% swinging strike rate since 2017, but as we’ll touch upon later, that’s partly a function of his overall approach. He threw it in the zone more often than most, but hitters have never been able to do much with it, and the pitch consistently drew lots of grounders and rated very well by batted-ball metrics. If the curveball needs optimizing, it’s probably as simple as throwing it in the zone less. Otherwise, it’s a major case of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

His changeup is close to a non-factor. He’s admittedly never had a good feel for the pitch, and he used it just 5% of the time in 2018 and 2019. This is why the slider he developed early in the 2019 season is so important. There’s a whole lot to be said about that slider, but—plot twist! The slider he developed in 2019 is gone, reportedly replaced by one a few ticks slower and with “more bite.” So we’ll talk about that in a little bit, but it’s worth noting that we’re going to be in wait-and-see mode with this pitch until we can watch it in action.

In the meantime, his fastballs give us lots to talk about. They bring serious heat but have spent the last five years generating inconsistent results in the majors. They present a confusing statistical profile, and I stopped and started this section about three separate times because I just wasn’t sure what angle to come from.

Were they actually good or not? That is to say, did they just need an adjustment or some kind of wholesale overhaul?

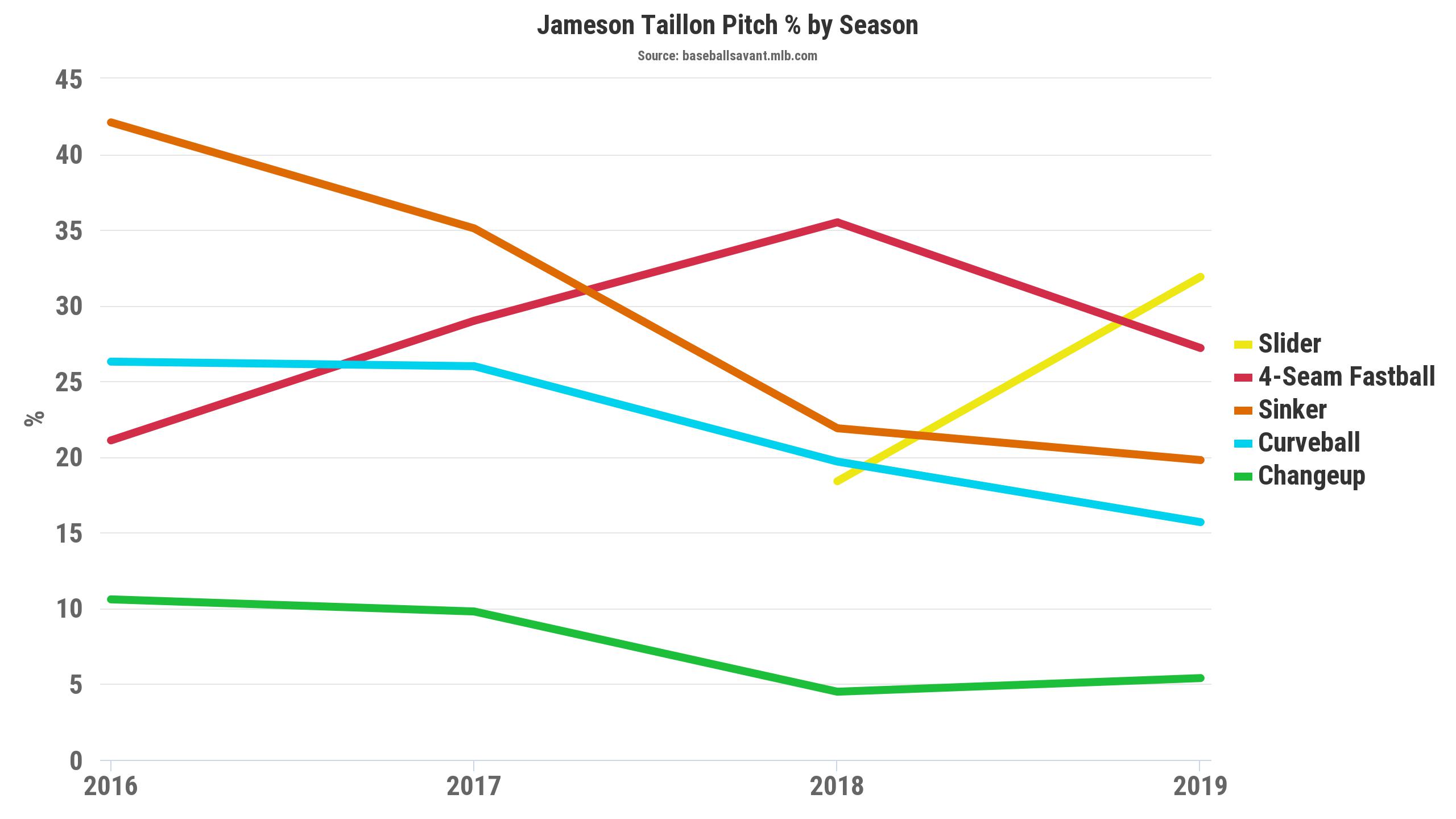

Even that distinction is totally nebulous, and as always, the answer is never clear and somewhere in between. But the good news is that even a decade later, it looks like there’s a path for Taillon’s heater to make him one of the better pitchers in the league. Before I walk you through getting there, let’s start with this chart of Taillon’s pitch usage over the past few seasons:

There are a few things worth noting, First, you have to appreciate a slider that comes out of nowhere mid-season to be a primary pitch within a year!

But let’s focus on the fastballs. If the Pitcher List community took it upon themselves to collectively raise a child, I have no doubt its first sentence would be something along the lines of “sinker bad! four-seam good!” That being the case, it’s promising to see that Taillon’s 2018 breakout coincided with a reshuffling of fastball priorities, especially from a pitcher who previously had this to say about their sinker:

“The two-seam is just a much more aggressive mentality, and I do put guys on the ground with it. I’ll throw bad two-seams in my head—out of my hand, I think they’re bad—and I’ll still put hitters on the ground with it.

With a four-seam, where you throw it is where it’s going to go. If you start middle with it, it’s going to end middle and guys are going to square it up. With the two-seam, I can throw it middle and it’s going to go down. Some days it runs, sometimes it sinks, but it’s always moving late, usually enough to miss a barrel.”

Just about any pitcher coming through the Pittsburgh system in the early- to mid-2010s would have been hard-pressed to avoid picking up a sinker and riding it like a ’97 Camry, so it’s encouraging to see that even before his injury, Taillon was breaking out of that contact-oriented, ground-and-pound mold.

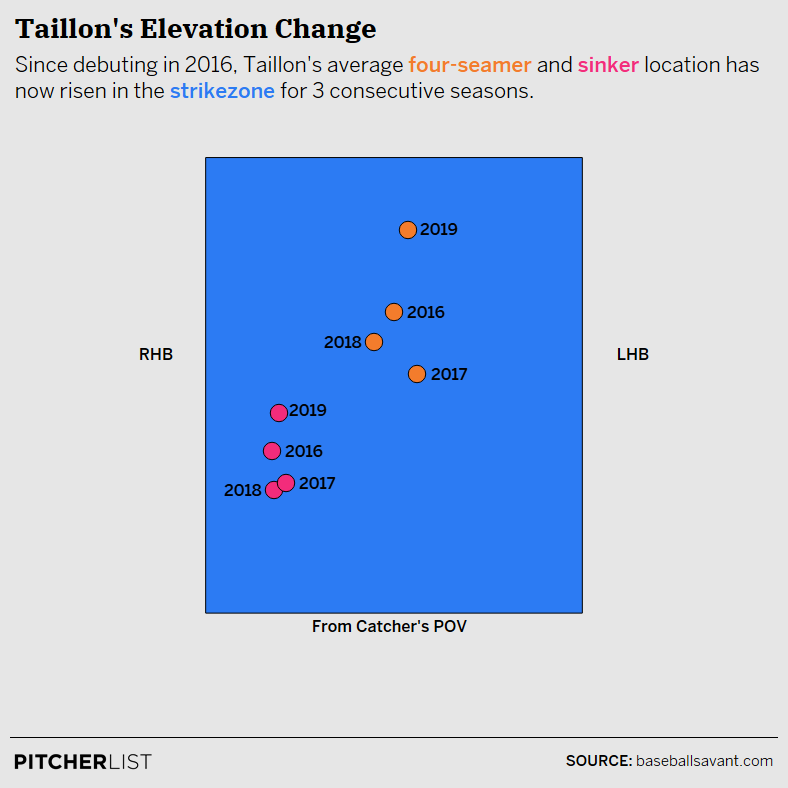

That goes for more than just pure pitch usage, too. Location, location, location. With good velocity, decent spin (2311 RPM in 2019), and a hammer curve, Taillon seems like an excellent candidate to start working up in the zone more with that four-seamer.

Relating to that, there’s good news and bad news.

The good news is that he was already well underway making the height adjustment, too. Here’s a visualization of his average fastball locations since his rookie year:

Very good! Thanks to sample size, it’s a bit hard to tell from heat maps, but Taillon was clearly aiming a lot higher with his fastballs in 2018 and 2019. Don’t worry about the location right down the middle. That’s partly what happens when you average out horizontal locations against lefties and righties.

Anyway, all that should be a good thing, but then there’s the bad news. We have to make sure it actually worked, first, and unfortunately, the numbers there are ambiguous:

| Year | wOBA | xwOBA | pVAL | Savant RV | Whiff% | SwStr% | CSW% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | .322 | .333 | -2.6 | 1 | 15.7 | 7.7 | 25.1 |

| 2018 | .317 | .291 | 4 | -2 | 24.6 | 12 | 31.2 |

| 2019 | .315 | .308 | -0.9 | 1 | 26 | 13.2 | 27.8 |

| Year | wOBA | xwOBA | pVAL | Savant RV | Whiff% | SwStr% | CSW% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | .393 | .343 | 0.5 | 7 | 17.9 | 9.2 | 22.4 |

| 2018 | .284 | .296 | 9.9 | -15 | 15.2 | 8 | 20.7 |

| 2019 | .301 | .372 | 1.4 | -2 | 17.5 | 9.1 | 25.5 |

Along with everything else across the board, both fastballs definitely improved with the switch-up in 2018, but we don’t know enough to do more than speculate on what level of correlation/causation there is between the two.

Regardless, they regressed in 2019, with the caveat of just a seven start sample size. What we can probably say is that the added height gave him more whiffs, though not necessarily enough (from a CSW standpoint) to make up for the decrease in called strikes that came with it.

That being said, throwing a few more pitches out of the zone in order to live upstairs isn’t really a bad thing. If you’re going to miss your target a little bit, a ball above the zone is a better outcome than leaving it right in the hitter’s wheelhouse.

Usually, it’s something a pitcher can live with if they’re picking up more whiffs at the same time. The problem here is that the increased height didn’t really add enough whiffs to make it a measurably better pitch. It was still a good pitch—those wOBA and xwOBA values are all better than league average—but given Taillon’s toolkit, the gulf in run values between the four-seamer and sinker is odd. For Taillon to reach his upside, he needs to get better results from his primary fastball, and with all likelihood, an improved four-seamer will let his sinker play up as well.

That being the case, the most concerning part of his four-seamer’s regression in 2019 is its performance at the top of the zone, where his swinging strike and whiff rates both fell by more than 6%. The reduced SwStr isn’t necessarily a bad thing. A slight increase in CSW on those top-third pitches from 36% to 40% tells us that it largely came from hitters just swinging less.

The downtick in whiffs per swing is more concerning, though. That top third of the zone is the golden area for getting whiffs on fastballs. It’s the spot where the hitter is least likely to make contact while still presenting the threat of a called strike. The league whiff rate on four-seamers in the top third of the zone was 25.5% in 2019, and on pitches at 94 MPH or above, that goes up to 28.6%. Taillon, however, has historically underperformed that benchmark quite a bit:

| Year | FB Velo | Top-Third Whiff% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 95 | 16.4 | |

| 2017 | 95.3 | 14.9 | |

| 2018 | 95.2 | 29.3 | |

| 2019 | 94.7 | 23.3 |

So there’s our logical conundrum, an issue that probably goes a long way towards explaining why even after the switch to the four-seamer as the primary fastball, the sinker remained considerably more effective by linear weights and run values.

Why did his fastball get worse results despite being thrown in ideal spots more often? Why does he get so many fewer whiffs on those pitches than he seemingly should?

In 2019, some of it probably had to do with small sample size, but four years’ worth of numbers don’t lie so easily. A look at how his fastball’s behavior has gradually changed over the past three years might provide some clarity:

| Year | V-Mov (in.) | H-Mov (in.) | Spin Direction (deg.) | Spin Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 13.9 | 5.9 | 202 | 65% |

| 2018 | 14.8 | 4 | 197 | 54% |

| 2019 | 17.2 | 1.3 | 190 | 42% |

(Source: Brooks Baseball; Baseball Savant)

It looks to me like there are two different things to be gleaned from this, which tells us that Taillon’s four-seamer has lost a not-insignificant amount of movement over his last couple of seasons pre-injury. Remember that for fastballs, counterintuitively, fewer inches actually indicates more vertical “movement”, as the optical illusion of the “rising” fastball comes from the ball dropping less than the brain thinks it’s supposed to.

Anyhow, to pick this apart, let’s start in the middle, with the ever-so-slight differences in spin direction, moving from about 202 degrees down to 190 degrees. This means that Taillon’s four-seamer replaced a little bit of sidespin with backspin. Put another way, if you can picture a clock face with a baseball spinning in the direction of the hour hand, it went from pointing at about 12:45 to about 12:15. This doesn’t seem like much, but it can make a big difference in the kind of side-to-side movement a fastball gets.

In this case, the effect was that Taillon’s fastball got straighter as its spin direction turned more upright, helping it lose almost three inches of arm-side run from 2018 to 2019, and almost five inches in total between 2017 and 2019. In a vacuum, this is neither a good nor bad thing. Those who can really get the best of all possible worlds (as Leibniz would have it) from their fastballs with good velocity, rise, and run are few and far between. Taillon can live with a straight fastball as long as it’s 95 MPH with a lot of ride.

The problem, as the chart indicates, is that straightening out his four-seamer didn’t give it any more ride, either. In fact, he’s added three inches of drop on the four-seamer since 2017, going from 13.9 inches to 17.2 inches. Where did that drop come from? At least some of the answer lies in the third column in that chart, in which we can see his average spin efficiency drop from 65% to 54% to 42%.*

That is, he’s started cutting the ball a lot more, which helps explain the lost movement on both horizontal and vertical sides. All that spin doesn’t mean much if it’s not going anywhere useful. In the end, even though Taillon was doing just about everything right in terms of approach, there’s just something about the way he was releasing the ball that made it easier to hit.

With a year’s worth of smoothing out the kinks in Hawkeye and the recently unveiled spin direction tools on Baseball Savant, we should have some pretty quick answers as to whether Taillon has corrected these fixable issues. His stated interest in pitch design gives me hope that it’s all being accounted for, because while he might not reach the scorching upper-nineties burn of former rotation-mate Gerrit Cole, his high-fastball/low-curveball combination could still carry him to a pretty big contract in another year or two.

But as I mentioned earlier, the fastball won’t be the only thing to keep an eye out for when he returns to PNC Park (or another yet to be determined location!) in 2021.

Apparently, he’s also spent his pandemic rehab time tinkering with his slider, and we’re likely to see a new version of it come 2021, with Jason Mackey of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporting that “in the past, [Taillon’s slider] was more like a cutter — thrown harder, prioritizing deception over movement. Now, Taillon said the spin on his slider has been much tighter, the pitch slower with more snap. ‘I love the way it’s spinning,’ Taillon said. ‘It’s more of a true slider.'”

Now, that’s being a little bit harsh on the slider he showed us in 2018 and 2019. It was still a pretty nasty pitch as it was, sometimes. This wipeout slider to Willson Contreras had more than enough bite to qualify:

As with the curveball, though, that kind of result wasn’t super common. His slider just a 14.7% swinging strike rate and 24.5% whiff rate over the two seasons he used it. That’s partially because, as hinted at about, he used it more like like a cutter than true slider, throwing it in the zone more than any other slider since 2018, minimum 500 pitches:

| Rank | Name | Pitches | Zone% | CSW% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jameson Taillon | 725 | 59.7 | 30.8 |

| 2 | Jake Arrieta | 1084 | 55.5 | 26.8 |

| 3 | Chad Kuhl | 557 | 53 | 36.6 |

| 4 | Ross Stripling | 858 | 52.3 | 24.8 |

| 5 | Jeff Samardzija | 804 | 51.1 | 27 |

| 6 | John Brebbia | 898 | 51.1 | 36.1 |

| 7 | Yu Darvish | 742 | 50.9 | 41 |

| 8 | Brett Anderson | 886 | 50.9 | 27.4 |

| 9 | Shawn Kelley | 810 | 50.7 | 29.6 |

| 10 | Jason Hammel | 780 | 50.5 | 31.6 |

Unless you’re Yu Darvish, it’s just hard to get enough whiffs on a slider thrown over the plate to make it a super-effective pitch. But again, that’s not necessarily what Taillon’s old slider was designed for. If this new slider is an attempt to miss more bats, it’ll probably look pretty different—we already know it has more break—and it will completely change the calculus on his arsenal.

The up and down is that it’s very easy for one to talk themselves into the idea that adding a true swing-and-miss pitch thrown beneath the zone could be the booster shot allowing his fastball and curveball to finally play to their full upside. If Taillon’s ability to spin the ball in the zone translates to spinning it just out the zone (or even up in the zone, if he wants to make unorthodox use of that big curve), he could find himself pitching his way out of Pittsburgh by the end of the summer.

To be quite fair, all of that is a whole lot to ask of any pitcher, much less one coming off their second major elbow surgery. There are a lot of attempted fixes happening at once here, and we should remind ourselves that Taillon will be beating the odds just be becoming a productive rotation member again, and that hopes and expectations should be tempered accordingly.

These things take time. But we know that attempts are being made, and when we get confirmation in April that Taillon is once again indeed a starting pitcher in the major leagues, we can look to see what adjustments are materialized. If a few things finally go his way, Taillon 2.0 might make sure we have no reason to count him out again anytime soon.

*Spin efficiency (also known as active spin) was calculated using baseball physicist extraordinaire Alan Nathan’s methodology, which may differ from the values found on Baseball Savant, which do not exist prior to 2019.

Photo by Shelley Lipton/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)