In 1941 Joe DiMaggio hit in 56 straight games, Ted Williams was over .400, and Bob Feller won 25 games.

By 1943 Joltin’ Joe was a sergeant in the US Army Air Force, the Splendid Splinter a Naval Aviator, and the Heater from Van Meter was a gun captain aboard the USS Alabama keeping his arm loose by throwing near the turret.

On the back of almost every baseball player’s card from 1942 to 1945 (or, ok, baseball-reference would make more sense today), you’ll find those years conspicuously absent for most ballplayers. These years sapped prime years from future inner circle hall of famers and literally thousands of other ballplayers scattered across the majors, minors, and independent leagues.

That was the environment across the country. That was the environment everywhere during World War II. It was all hands on deck and not one industry was spared, baseball was no different. Some of the brightest stars enlisted before the draft was implemented like Bob Feller, while others did their duty and answered the call when their turn came. In the weeks following the attack on Pearl Harbor, baseball had an uncertain future, a decision had to be made whether or not to continue the sport and that decision came down from the highest heights possible: Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

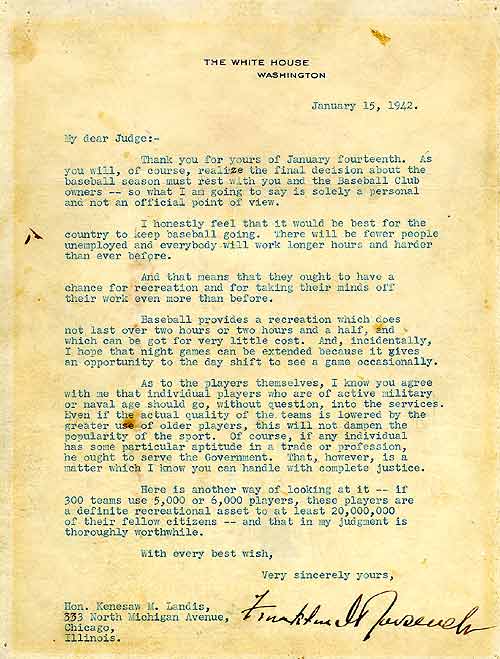

The Letter

The war had been raging in Europe for years in 1942, but the United States were newcomers. The country didn’t know war weariness or the other pressures war wroughts on nearly every facet of life. Both people and companies enthusiastically jumped up with any and all efforts to help the “boys overseas.”

Baseball Commissioner Judge Landis wanted to make sure his sport was doing its part as well, and a little over a month after the United States declared war he wrote to President Roosevelt, “The time is approaching when, in ordinary conditions, our teams would be heading for Spring training camps. However, inasmuch as these are not ordinary times, I venture to ask what you have in mind as to whether professional baseball should continue to operate”

The president – probably one of the two biggest fans of baseball the presidency has ever seen – wrote back immediately the following day answering with the famous Green Light Letter.

“I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going… If 300 teams use 5,000 or 6,000 players, these players are a definite recreational asset to at least 20,000,000 of their fellow citizens – and that in my judgment is thoroughly worthwhile.”

Roosevelt’s Green Light Letter provided by the National Archives

The letter was a rousing yes. Baseball would continue – albeit with restrictions and talented rosters subjected to the realities of all-out war.

Older players would continue to play, as would players that suffered injuries rendering them unable to participate in the military. But while many of the stars would pause the baseball careers and join the service, the game would go on, and for good reason as Roosevelt reasoned.

Rationing was implemented across the country. The luxuries and resources used in everyday life were greatly limited, resources like gasoline and rubber. With the supply of tires and gas for road trips severely diminished, it was believed that people would look closer to home for much-needed entertainment after long days working in factories. Baseball would be good for the country, and baseball agreed.

The legendary Connie Mack responded the next day, “That is exactly how I feel about continuing baseball. As I told the United Press recently on my 79th birthday, I feel it will be an excellent thing for the morale of the nation.”

Casey Stengel, the great baseball philosopher as the newspapers called him, weighed in with his thoughts, “The average human mind can handle only so much trouble and brooding. It needs some form of release now and then. The entertainment and the amusement baseball brings to millions will be badly needed. And this can in no way interfere with war work of any sort.” To which the newspaper ended the line – to great amusement – with, “At which point the seamy-faced Mr. Stengel bit roughly into another cigar.”

Brooklyn Dodger President Larry MacPhail was one of the first to voice a response from the business of baseball side, “I believe baseball can contribute a lot… clubs will aid in publicizing the sale of defense bonds…”

War Bonds & Night Baseball

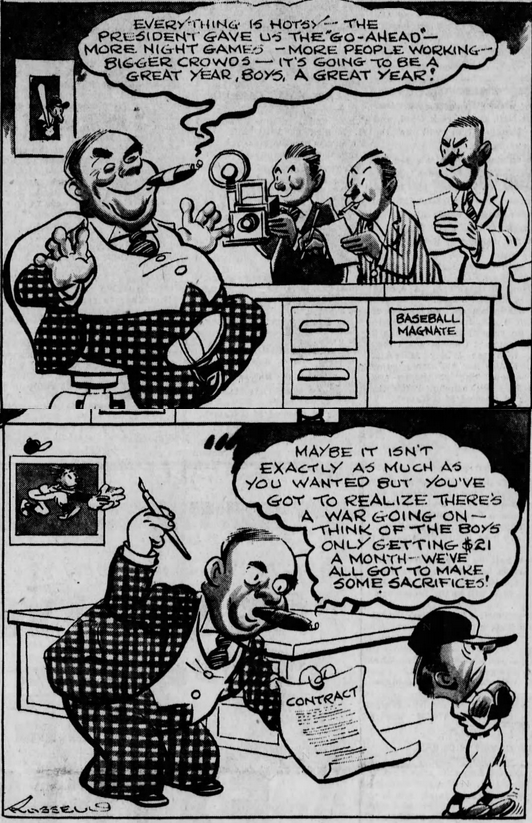

Before baseball could resume in 1942, team owners had to agree on financials (impossible to believe) and even when games would take place. Baseball was hardly different than any other wartime company in that the promotion and sales of war bonds were a priority.

One early proposal saw a certain percentage of gate revenue be donated directly to the war effort. What better way to support the “boys overseas” than a direct contribution? The owners didn’t see it that way and the proposal was swiftly voted down during the first meeting, it was left up to the individual teams to donate a percentage of gate receipts.

Teams and players would contribute in other ways. During negotiations for the 1943 season, it was agreed that one-tenth of salaries would be converted into defense bonds, and certain games would be dedicated to fundraising and selling those war bonds. The ’43 All-Star game, for example, was the first midsummer classic to be played at night, and while fourteen All-Stars from the previous year were off in duty, the 31,938 fans in attendance at Shibe Park raised nearly $200,000.

Cincinnati Enquirer, Jan 18, 1942

A separate “War Bond Game” was also organized, but this game wasn’t a normal All-Star game. Major League Baseball reached deep into their history and pulled out players like Cy Young, Ty Cobb, Lefty Grove, Honus Wagner, and Babe Ruth to appear for the game. The 35,000 fans watching the game raised a huge amount of money, and the crowd got to see the Babe take Walter Johnson deep for Babe’s final home run in a stadium.

Another decision to make was how many more games should be played at night. President Roosevelt strongly encouraged the league to increase the number of games played in the evening so that factory workers could spend a few hours relaxing after their shift. The problem was that most of baseball didn’t care for night games. The season before in 1941, only seven games per club were played at night. Baseball under the lights was a novelty.

A novelty that many saw as dangerous.

“The greatly increased number of night games can’t help but hurt the players.” Babe Ruth, then retired for half a decade said. “Playing such a large number of night games probably will weaken – and may even ruin – their eyes. The change of diets also is going to have an effect… It’s good for the fans – as long as the ball players last.”

Damage to eyesight was one thing, but some fans were concerned about an entirely different danger. The bright stadium lights, one fan reasoned, “may tip off enemy bombers of that fact and they could plan their destruction accordingly.”

Both of those fears ended up unfounded, and after Roosevelt’s letter, each team at least doubled the amount of night games from the prior season.

The Enlisted

Some saw Roosevelt’s Green Light letter as baseball skirting the war and avoiding their patriotic duties. The New York Times published a letter to the editor admonishing the sport:

“Don’t they [baseball officials and draft boards] realize that our country is at war for the preservation of our rights and freedom and that we need all the manpower available both for active and noncombat service?”

The assumption that baseball players and their support infrastructure would be exempt proved fruitless. The Selective Training and Services Act, better known as the draft, required all men between the age of 18 and 45 to register for military service. Baseball, with its athletes in the prime of their prowess, was picked through with nearly reckless abandon.

4,076 Minor League players were plucked from their teams and placed into service – 607 alone enlisted the day after Roosevelt’s letter. Thousands more independent league and collegiate ballplayers marched to war as well, and the Majors and Negro leagues sent hundreds of their own.

The baseball family worldwide was no different. Professional Japanese players and even Australian ballplayers joined the war. Bob Feller famously saw combat in the Philippine Sea, and Yogi Berra served on a Navy rocket boat on D-Day in Omaha Beach and was awarded the Purple Heart. Yogi said of that day,

“The sky was a black cloud full of planes, the cliffs were orange and exploding and it seemed as ‘green ants’ swarmed all along the shores and cliffs. It was a view I’ll never forget. I’m thankful I was there.”

Three former Major Leaguers, Charlie Frye, Elmer Gedeon, and Harry O’Neil would give their lives in the war, and far too many ballplayers were lost in every country that sent them.

Those harsh realities were why Roosevelt was inspired to write his Green Light Letter. Yes, baseball would contribute its resources and people, but folks home and abroad needed baseball as a respite from the onslaught of merciless newspaper headlines. Major League Baseball, and famously the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, were happy to do their part.

Featured Image by Quincy Dong (@threerundong on Twitter)