One of the themes of the 2024 season has been the successful transition of a handful of relief pitchers back to the starting rotation. That’s not usually the direction these transitions go. The “failed starter” archetype (and t-shirts) exist for a reason.

In the cases of Garret Crochet and Jordan Hicks, their time in the bullpen had less to do with showing they couldn’t start and more to do with lack of opportunity because their teams wanted to fast-track their high-octane stuff to the major league bullpen to help contending rosters.

Reynaldo López, on the other hand, was a textbook case of “failed starter.”

Acquired by the White Sox from Washington before the 2017 season, López started 96 games and posted a 4.75 ERA and 4.90 FIP over 513.1 innings from 2016 to 2021. Those run-prevention marks ranked 91st and 95th out of the 100 starting pitchers to throw 500+ innings over that span. (As a fan of the rival Twins, I used to snarkily tell anyone who would listen that López was my favorite Sox hurler to face.)

The Sox finally pulled the plug in 2021 and gave relief work a shot. López streamlined his arsenal to primarily his four-seamer and slider, bumped his velocity up to the high-90s in shorter stints, and was shielded more often from the left-handed hitters that had tormented him in the rotation. He emerged as a solid reliever (2.95 ERA, 3.02 FIP in 149.2 IP) in 2022 and 2023, and was acquired by buying teams twice last summer before hitting free agency.

When the Braves gave López a 3-year, $30M deal last winter, it seemed they were adding him to their collection of well-paid, late-inning arms. Instead, López was surprisingly instructed to stretch out in Spring Training for a return to starting and installed in the Braves rotation.

After 17 excellent first-half starts, López entered the 2024 All-Star break leading the major leagues in ERA (1.88) by a wide margin. While it’s not unheard of for failed starters turned relievers to re-emerge as starters, it certainly is not a common occurrence, and it’s definitely not common for them to become All-Stars and produce front-of-the-rotation numbers.

It all begs the question: Should we believe in Reynaldo López?

Starting vs. Relieving

There are a few criteria that typically distinguish pitchers with the skills to start from those who need to be pushed into relief. Our Michael Barker covered these in-depth last winter and they included:

- An uncommonly diverse arsenal of pitches with good stuff and/or unique shapes

- Above-average command for a reliever

- Neutral platoon splits that allow the pitcher to get both righties and lefties out consistently

To that list, I would add the ability to hold their velocity and quality of stuff for 90 to 100 pitches.

Now, adherence to these criteria is perhaps looser now than at any time before. The line between starter and reliever continues to be blurred and more teams are optimizing for quality over quantity. Nonetheless, this remains a useful framework for assessing a pitcher’s capacity for longer outings, which we can apply to López for our work here today.

Depth of Arsenal

In the ‘pen, most relievers skinny things down to their two best weapons, as López did, but that can be harder to do when facing hitters on both sides of the plate two or three times in a given game.

For example, in the past two seasons, in relief, 57.3% of the hitters López faced were right-handed and he did not face a single hitter more than once in a game. He delivered fairly neutral platoon splits in that span, performing 16 points of wOBA worse against lefties (.282) than righties (.266), but holding both to solid numbers.

So far in 2024, he’s faced ~55% left-handers and ~60% of the batters he’s faced have come in the second, third, and fourth times through the order. Even in the “throw your best stuff as often as possible” era, that’s a different task for a pitcher.

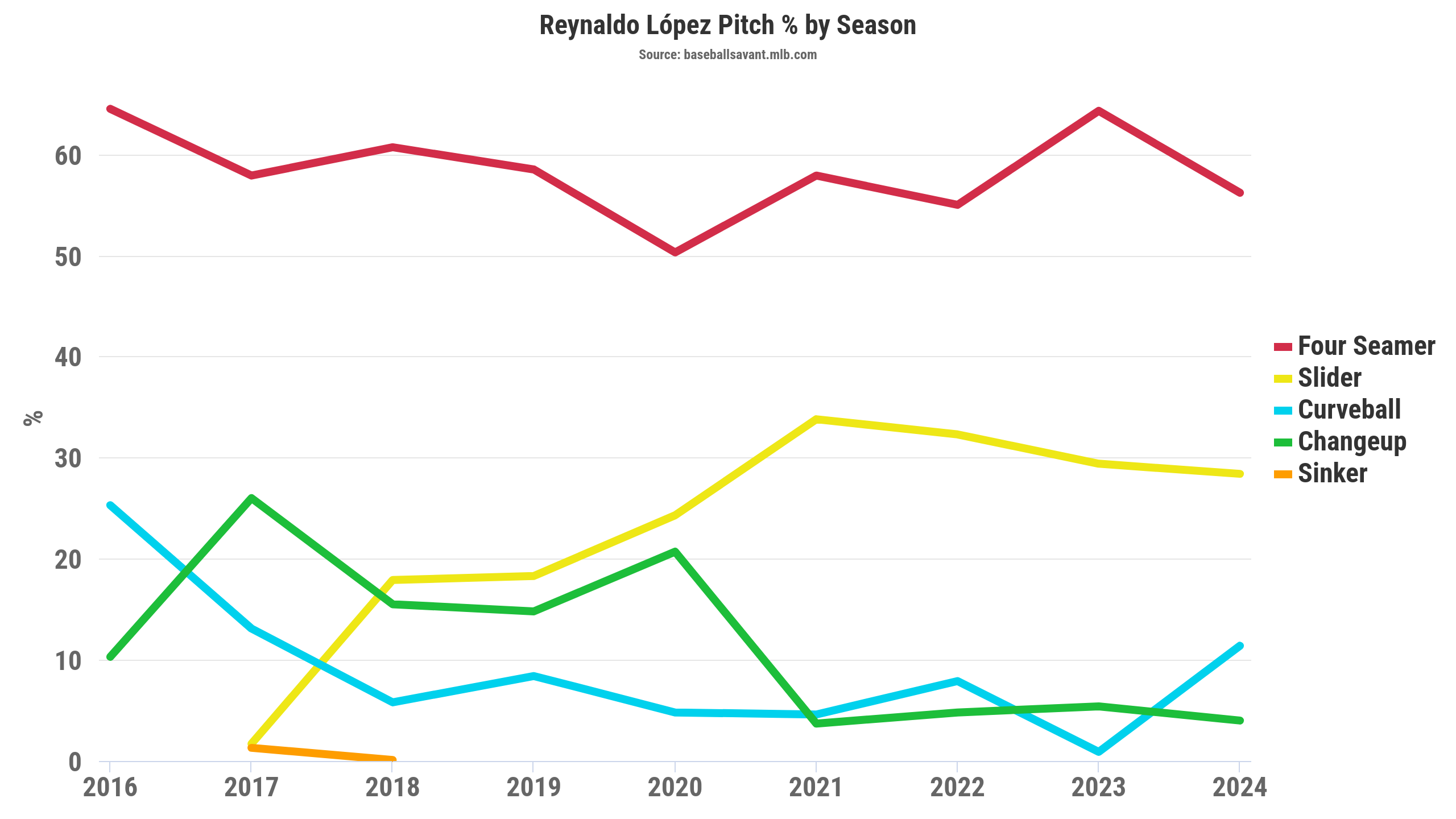

In response, López has made modest changes to his pitch mix this season:

You can see above he’s remained heavily fastball-slider-centric overall. That’s especially the case against right-handed batters, against whom four-seamers and sliders make up more than 97% of his pitches this season. That approach has held right-handers to a weak .242 wOBA.

Against lefty opponents, he’s mixed it up more but still goes to his four-seamer and slider about three-quarters of the time, which is generally in line with how he operated as a starter previously.

The main adjustment is that he’s now preferring his curveball as his third pitch to lefties (about 18% usage), instead of his ineffective changeup (7.1%) which had comprised about 20% of his offerings in the rotation before.

Reynaldo López, Filthy 77mph Curveball. 😷 pic.twitter.com/JikFTpXHUL

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) June 6, 2024

Based on the results this season, swapping out changeups for curveballs makes good sense. His changeup has allowed a .529 wOBA and accumulated -3 runs in its limited action this year, per Statcast, while his curveball has held opponents to a minuscule .150 wOBA and been worth +5 runs.

That swap, however, has not helped López maintain the small platoon split he had as a reliever. Lefties have run a .314 wOBA against him this season, almost 80 points better than what he’s allowed to righties. That said, he has done somewhat better against the southpaws than he did as a starter earlier in his career when he allowed .332 wOBA to them.

The issue there is mostly command-related. López has walked more than three times as many left-handed hitters (12.7%) than he has right-handed (3.8%), and his overall 8.7% walk rate is comfortably below average for starting pitchers, ranking 62nd of 82 pitchers with 100 or more innings pitched this season.

Holding Up

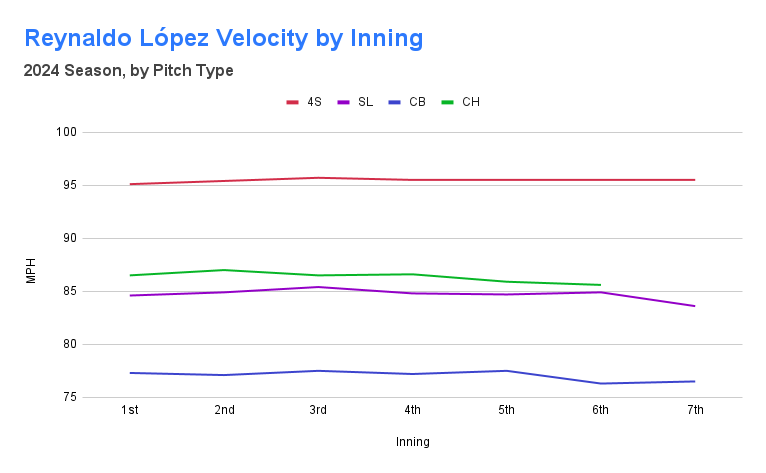

Next, let’s move on to my additional criteria. When Michael Baumann checked in on López for FanGraphs in May, he noted that López’s velocity was holding up as he worked deeper into games. Naturally, López’s velocity is down about 3 mph compared to what it was when he was relieving last season. But, he remains in the top quartile for velocity among starting pitchers and he’s maintained his velocity on each of his pitch types throughout his outings, as you can see here:

Data from Baseball Savant

That’s helped López maintain his run prevention and contact suppression when facing hitters a second time, as you can see from the numbers in the table below.

However, there’s some reason to think that’s not a fully truthful story. The table also reveals he’s walking more hitters and striking out significantly fewer hitters the second time through. While the results have been good, it seems he’s been somewhat fortunate in those second trips through lineups.

Moreover, as happens to a lot of starting pitchers (and especially those who rely on two main pitch-type offerings), things have taken a turn for the worse when the Braves have let López see a lineup a third time. This is a smaller sample than the other two bins, so may have some noise, but the pattern of walks allowed and strikeouts both moving even further in the wrong direction and his slugging percentage allowed shooting up is consistent with what we’d typically expect.

This undoubtedly has some bearing on Atlanta being fairly cautious with López’s workload.

He’s already thrown 38.2 more innings and 400 more pitches this season than he did all of last year. While he’s averaged nearly 5.2 innings across his 19 starts (a healthy average), he has surpassed 100 pitches only once and been removed before reaching 90 pitches ten times, a figure that doesn’t include his most recent outing where he was lifted after 57 pitches thanks to forearm tightness. (Thankfully, he appears to have dodged serious injury and may not miss any time, with the results of an MRI coming back clean).

The Braves have also used their schedule and pitching depth to buy López extra rest between starts when they can. Ten of his 19 starts have come on the modern schedule of four or five days’ rest, and they have found ways to get him eight starts with six or more days of rest.

Dancing with Fire

So, against the criteria that Barker put forward and that I modified, López isn’t really doing any of them at a high level this season. That said, none of them are particularly bad, either. An accurate description of his skills as a starter (by this framework, anyway) might be “just on the low side of average.”

That doesn’t come close to explaining a league-leading 2.06 ERA. So, how has he been doing this?

At the simplest, we can just point to the discrepancy between López’s ERA and other run prevention estimators. His FIP is 3.16, a full run above his actual ERA, and the 6th-largest difference among 68 qualified starters this season.

That’s due in some large measure to the fact that he’s allowed just 0.60 home runs per nine innings this season, which is about half his career rate. Just 6.4% of the fly balls López has allowed have gone over the fence, well below his 10.8% career mark. He’s also benefitted from some good fortune in stranding baserunners. His strand rate (LOB%) is 86.1%, thirteen points above his 73.1% career rate.

His xFIP, which normalizes home runs allowed to the league average, is 3.84. SIERA puts him at 4.02. Statcast’s xERA has him at 4.33. Whatever your metric of choice, they all agree that López is a bit out over his skis this season.

It seems likely that both the success at stranding runners and keeping the ball in the part will correct back toward their respective means in the second half. That seems especially the case because López is a fly ball-oriented pitcher, generating ground balls on just 38.1% of his balls in play this season (the league average is 44.5%).

In the last ten full seasons (no 2020), there have been just two starting pitcher seasons where a pitcher maintained an HR/9 under 0.70 while generating groundballs on less than 40% of their balls in play: Justin Verlander with Houston and Carlos Rodón with San Francisco, both in 2022.

And it’s not just home runs, but damage on fly balls in general. Among the 180 starters who have allowed at least 25 fly balls this season, López has the 2nd-lowest wOBA allowed (.202), trailing only the Phillies’ Cristopher Sánchez (a sinkerballer). As a group, those starters have allowed a .426 wOBA and .796 slugging percentage on fly balls and there isn’t anything compelling enough in López’s batted ball quality data to suggest he suppresses fly ball damage this much better than everyone else.

So, should we believe in Reynaldo López? I think yes and no. What he’s done so far this year has some hallmark characteristics of a mirage and we should not believe in him as a potential ace who will consistently post sub-3.00 ERAs. But, even with a fair bit of regression, he’s shown enough that we can probably believe in him as a mid-rotation or back-end starter.

That’s still highly valuable and the Braves are making out like bandits on this acquisition and their decision to transition him back to starting. Starting pitching is expensive to acquire — just take a look at what other 4th and 5th starter types fetched in prospect value at the trade deadline or consider their $12-15M a year going rate in the free agent market last winter — and that they’ve conjured up a viable one from a reliever being paid like a good reliever is a nifty bit of front officing.

Photo by Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Aaron Polcare (@bearydoesgfx on X)