Coming out of the 2021 season in which he returned to form (and health), right-hander Alex Cobb was a popular sleeper choice among baseball analysts last winter. He’d worked 93.1 innings for the Angels, his most extensive workload since 2018 when he worked 153.1 innings for Baltimore and was largely effective in posting a 3.76 ERA and 2.92 FIP.

Analysts loved Cobb’s 53.3% ground ball rate, his career-high 24.9% strikeout rate, his second-half velocity uptick – 93.2-mph average in the second half vs. 92.5-mph in the first – and pointed to his .315 batting average allowed on balls in play (BABIP) while pitching in front of the Angels’ 23rd ranked defensive infield as another reason to believe in him going forward.

The San Francisco Giants apparently agreed with that optimistic assessment and inked Cobb to a two-year, $20M deal (with a $10M option for 2024) right before the lockout. The move to San Francisco’s pitcher-friendly home park and strong infield defense only served to add fuel to the Cobb hype train.

For most of his career, Cobb had worked in the low-90s with his sinking fastball and his signature pitch had been a devastating split-changeup dubbed “The Thing.” In late March, reports started flying out of Arizona that Cobb was throwing 94-97 mph with his fastball at age 34, an increase he credited in large part to offseason training at Driveline.

“Multiple scouts have heard that (Alex) Cobb, whose fastball averaged 93 mph last season, is hitting 97 these days.”

…excuse me? https://t.co/EKl4mdPBe8

— Alex Fast (@AlexFast8) March 31, 2022

A velocity increase. More strikeouts. All the groundballs. A favorable park and defense behind him. Good health. All the pieces seemed to be in place for a breakout campaign.

But sometimes baseball isn’t that simple.

A Rocky Start

Cobb’s first outing in San Francisco went according to plan. The Giants scored ten runs in the first two innings and Cobb cruised through five innings against the Padres, allowing just two runs and punching out 10 batters. His second start was more of the same through four innings against the Mets. Cobb had allowed a single run when things then took a turn in the fifth inning — three runs scored and he was lifted with an adductor injury that led to an injured list placement.

Upon returning from the injury, Cobb’s third start was a disaster – four hits, three walks, and an error led to five first-inning runs against the lowly Nationals — and he experienced a first-inning pitching change in the shortest start of his career.

Two strong starts followed, and then came two more very bad ones, both with ten hits allowed – a seven-run outing in Colorado and a six-run struggle against the Mets. By May’s end, Cobb had a 5.73 ERA across just 37.2 innings and was back on the injured list with a neck strain.

Had all that pre-season steam proven to be misguided?

A Strong Finish

Cobb returned from the injured list for the second time in mid-June and made two middling starts to finish out the month (combined 8.1 innings, five runs, two earned, eight hits, 6:2 K:BB). For the rest of the season, Cobb did not have any noteworthy workload restrictions or injuries. Once the calendar flipped to July, success was found and would stick the rest of the way. Cobb made 18 starts July-October, working 103.2 innings with a 3.13 ERA. Cobb allowed more than three runs in a start three times in the stretch while holding his opponents to zero or one run eight times.

While the Giants fell from contention, Cobb proved to be a stable bright spot in their rotation. By season’s end, he had thrown the third-most innings on the club and finished tied for 22nd in MLB with Luis Castillo, and just ahead of Nestor Cortes and Triston McKenzie, in pitching fWAR. In the second half of the season split, Cobb was tied for eighth among pitchers in fWAR.

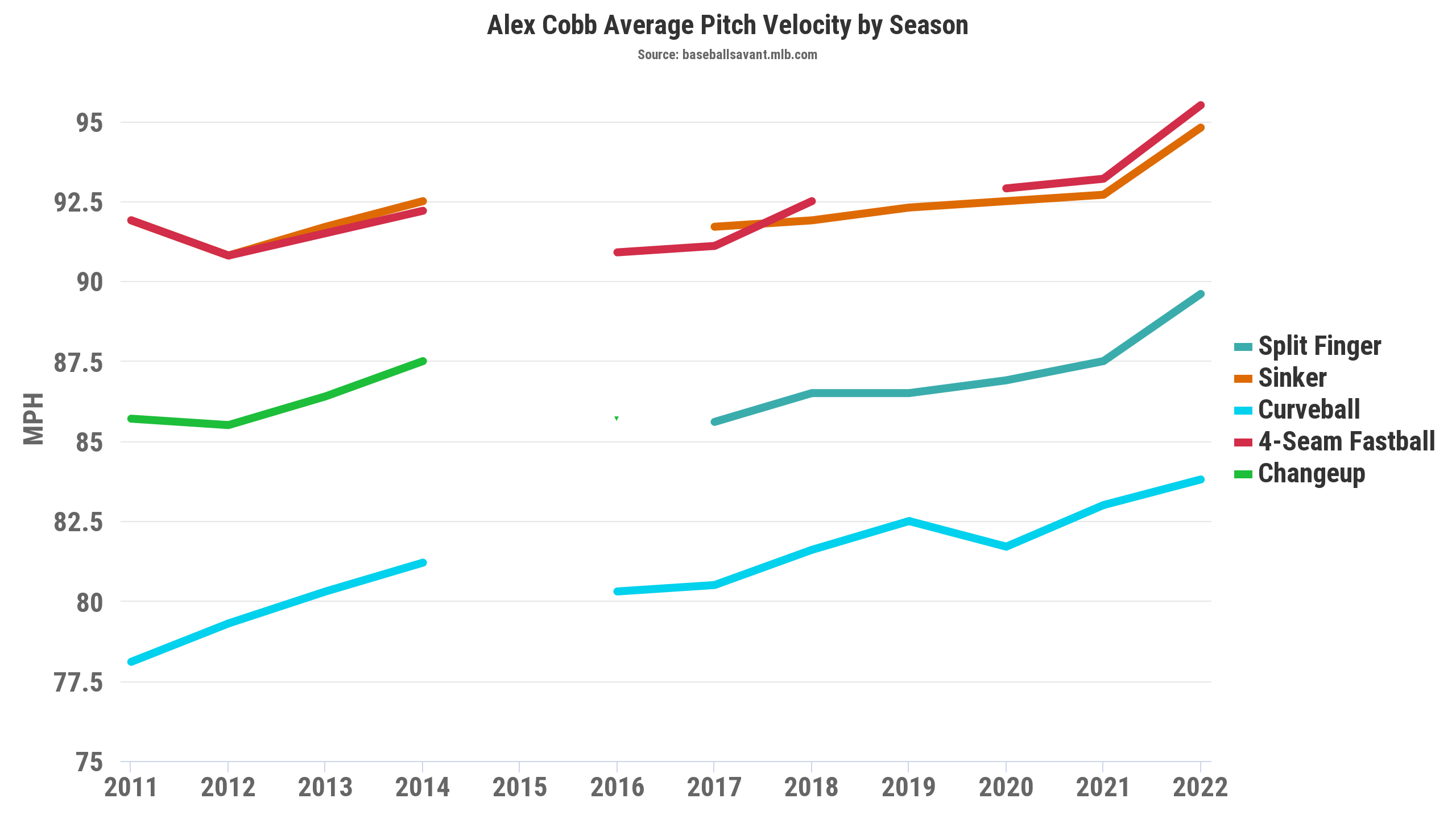

The preseason velocity uptick proved to be real and stayed consistent throughout the season. Cobb was in the 71st percentile in fastball velocity – the first time he’d been above average in the Statcast era – and he had the highest average velocity of his career on all his pitches:

After a Spring Training game in April, Cobb spoke about the expected benefits of his new velocity. “I would like to say I’ll be freer to miss with location a little bit,” Cobb said. “I had a couple of fastballs today where they leaked middle and I got weak-hit ground balls. Maybe if they were a tick or two [slower], that’s right on the barrel.”

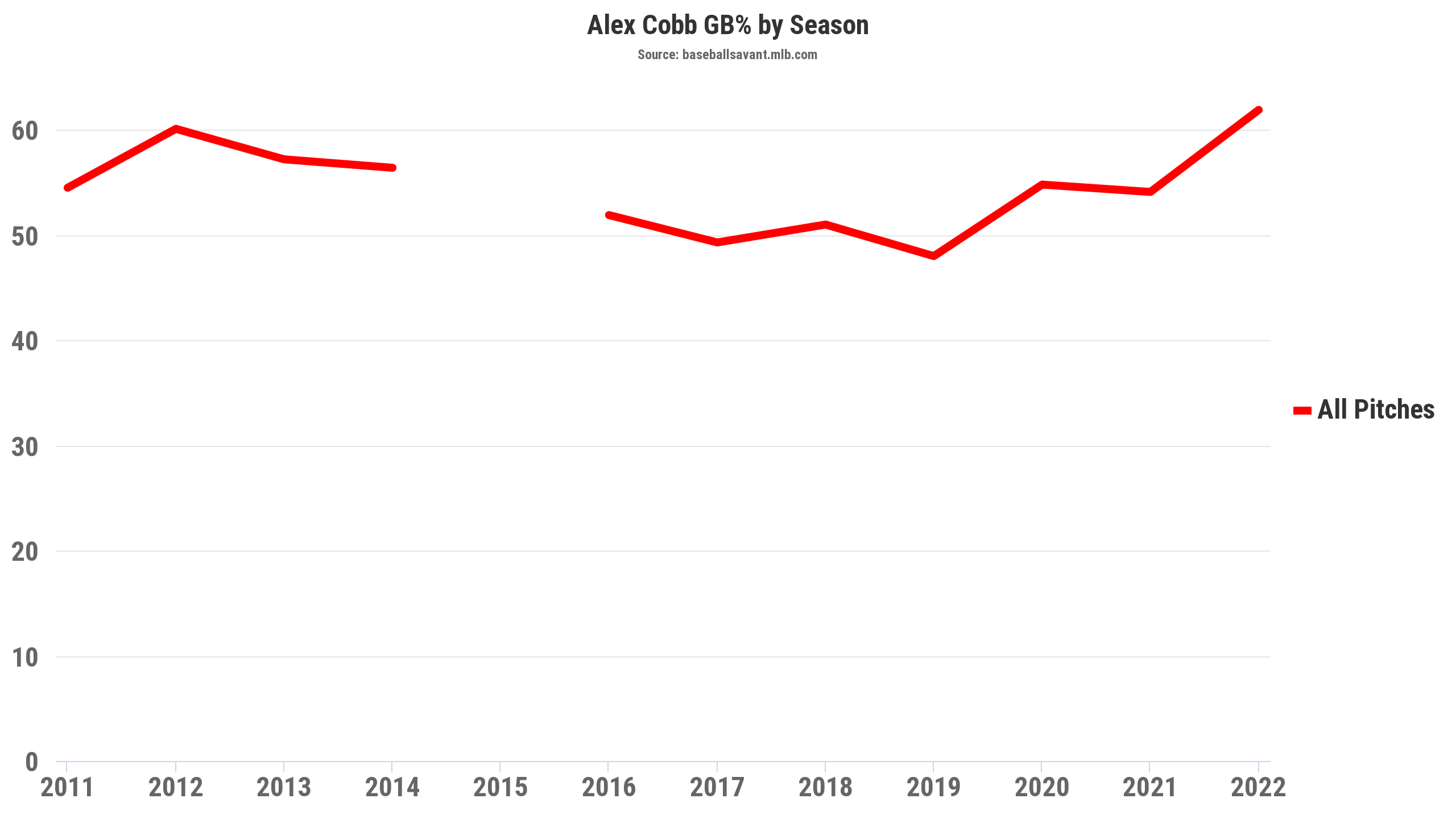

In hindsight, those comments look prophetic. Cobb’s rate of generating ground balls was 61.9%, the highest of his career and second highest among all pitchers to throw at least 140 innings (trailing only Framber Valdez). Similarly, and relatedly, his barrel rate allowed (barrel/PA) was 2.5% and also a career-best.

Mostly Misfortune

Often, in these kinds of articles, this would be the part where I would painstakingly walk you through all the amazing adjustments that Cobb made to turn his season around.

But, that’s not what happened.

He didn’t add a new pitch or make any big changes in his pitch mix. He kept working with his sinker and split-changeup about 85% of the time, mixing in curveballs for the rest. He didn’t make noticeable changes to his locations or how he used those pitches. His velocity and movement profile stayed nominally the same.

In actuality, even during his tough start to the season, Cobb was pitching quite well. All the reasons for optimism for Cobb from the preseason were still there. While he posted that ugly ERA in the first half, he had punched out 26.5% of the hitters he’d faced while walking just 7.0%. He’d generated ground balls on 62.3% of the batted balls he allowed.

All the elements for success were there, but Cobb had the second-largest delta between his ERA (5.09) and his expected ERA (3.20) in baseball at the time. Other run prevention estimators agreed he’d thrown much better than the surface stats showed. To wit, Cobb’s FIP and SIERA at the end of June were 2.69 and 2.96, respectively.

Mostly, Cobb experienced terrible luck, evidenced by the fact that he had an absurdly high .370 BABIP and an absurdly low 55.0% left on-base rate.

Further illustrating how poorly the surface numbers reflected how well he had pitched were his differing wins above replacement (WAR) estimates. To that point in the season, Baseball-Reference’s version of WAR, which uses runs allowed per nine innings as an input, pegged Cobb as a below-replacement level (-0.7 bWAR) pitcher. Contrastingly, FanGraphs’ version, which uses Fielding Independent Pitching as an input, had Cobb at positive 0.9 WAR.

In the second half of the season, when Cobb found success, he actually got slightly fewer strikeouts and ground balls. From July onward, he struck out 22.7% and coaxed grounders on 61.1% of the pitches put in play against him, both about four points less than the season’s first half and something that you would think would hurt him. Those marks were still average or better, especially the ground balls, but those minor regressions were almost entirely offset by things getting back closer to normal in the luck department. His BABIP and strand rate after July 1 were .322 and 74.2%, respectively, leading to a very high-quality FIP mark of 2.62.

Luck Isn’t Everything

It’s probably simple enough to just point to the randomness of luck and call it a day when evaluating Cobb. That certainly played an important role for him in 2022. But, so did the Giants’ defense behind him.

The 2021 Giants were a top-ten defense and turned 70.7% of balls hit into play into outs, the sixth-best rate in the game, per Baseball Reference. On ground balls, opponents had just a .229 batting average. In total, Statcast rated the Giants’ infield defense as the 4th-best, with +22 outs above average (OAA).

In the first half of 2022, though, when Cobb was experiencing his challenges, the Giants allowed a .272 average on ground balls and had -20 OAA from their infield. Given that, it’s probably not too surprising to learn that the Giants ranked 23rd in infield defense per Statcast in May, and in June they were ranked dead last. As a group, Giants’ infielders posted -5 OAA playing behind Cobb in the first half.

That no doubt contributed to Cobb’s misfortune and is illustrated by the results Cobb got on ground balls with different launch angles:

Generally speaking, the lower the launch angle, the less productive the batted ball. But, you can see from the table above that even the balls in play off Cobb that were beaten straight into the ground were productive much more often than they should have been early in the season. The average exit velocity on ground balls hit more steeply than -15° off Cobb had the same 78.6-mph average exit velocity in the first half and second half. But the results were starkly different, thanks in large part to injuries to well-regarded fielders like Evan Longoria, Brandon Crawford, and Brandon Belt, especially early in the season.

Things improved modestly as the season progressed, due in part to better health, particularly of Crawford and his 92nd percentile OAA. In July, the Giants’ infield defense rebounded to 7th in OAA and stayed in the top ten each month for the rest of the season. When Cobb was on the mound in the second half, the Giants’ infield graded out with +3 OAA.

Is that just coincidental with Cobb’s “luck” evening out? Probably not. It probably played an important role for him.

In the end, whereas Cobb’s ground ball compatriot Framber Valdez pitched in front of an infield that posted the game’s second-best OAA mark (+10) when he was on the mound, Cobb’s infield support ranked 161st of 204 qualified pitchers with -3 OAA and the 2022 Giants converted only 67.4% of their balls in play into outs, a mark that ranked 29th.

Going Forward

I do think we can buy into Alex Cobb’s 2022. All the elements that had us excited about him before last season – tons of grounders, slightly above-average strikeouts, limited walks, increased velocity – are still there and were demonstrated throughout the 2022 season. Those improvements served to raise Cobb’s floor from the prior few years. Further, his overall .336 BABIP last season was the highest of his career, nearly 30 points worse than his .297 career mark, and research has shown that aberrant ground ball batting averages tend to correct over time.

That said, it’s worth remembering the kind of pitcher Alex Cobb is. While the extra heat enabled him to meaningfully increase his strikeouts from his prior career norms and gave him some more margin for error in the zone, he is still a ground ball pitcher first. And ground ball pitchers are dependent on the defense behind them to turn contact into outs. We should believe in, but be clear-eyed, about what Cobb brings. And we have to understand that what the Giants do to affect their glovework this winter could go a long way toward determining if Cobb can sustain this or even add another level to his late-career renaissance.

Photos by Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)