When I think of the most impactful plays in baseball, a few things come to my mind. On the hitting side, the obvious answer is the home run, carrying with it the chance to completely change the flow of a game with one swing. On the pitching side, the swinging strikeout stands out to me as a real momentum killer and pitcher-pumper-upper. A few weeks ago, I found that home runs were actually the least meaningful type of base hit in terms of changing the subsequent batter’s behavior (i.e., their swing percentage on the first pitch). Will the influence of swinging strikeouts prove similarly contradictory?

Count Walk-ula

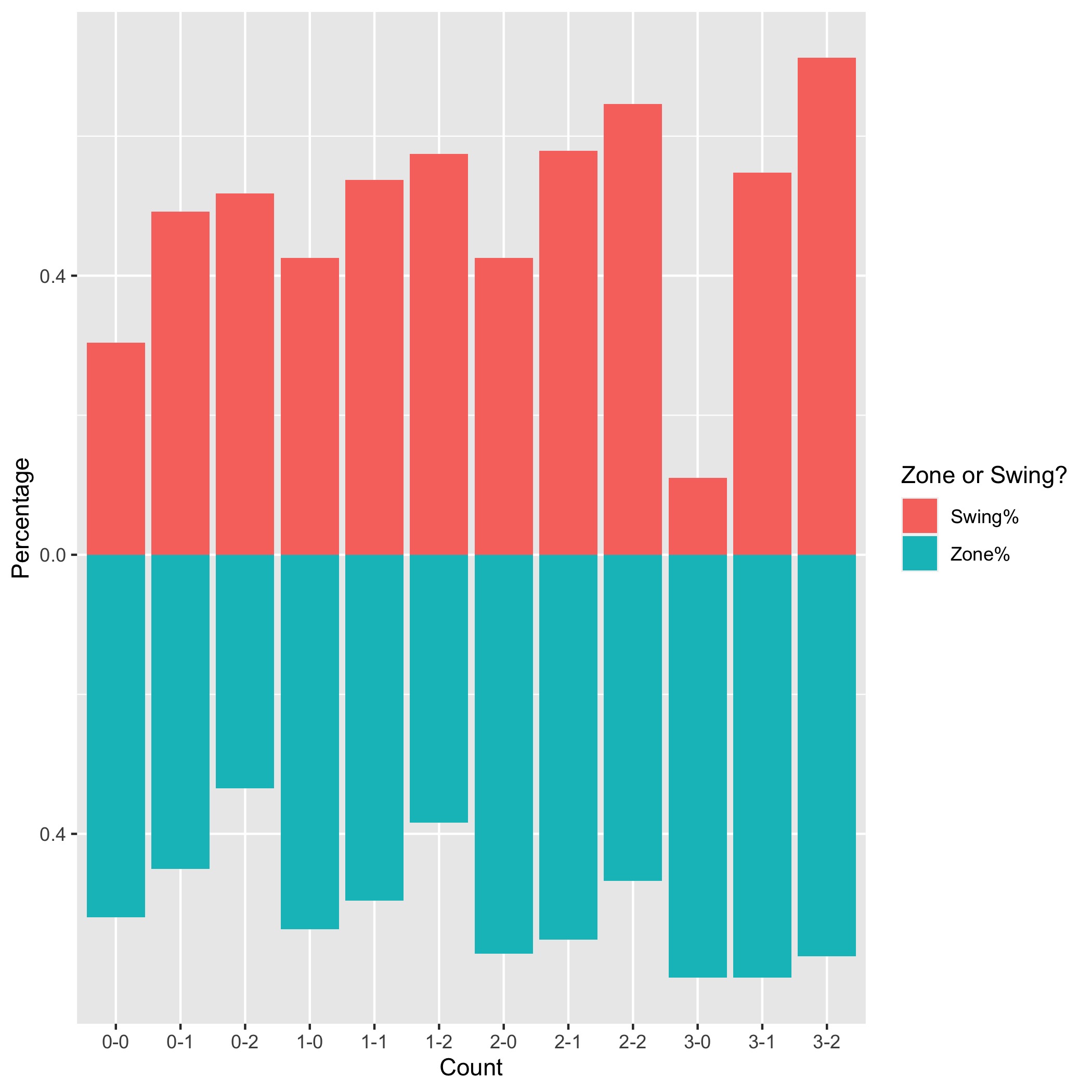

To start, let’s review a basic fact about hitters. Their swing percentage is highly dependent on count:

Pitchers, too, rely on the count to guide their strike-throwing:

Or, if you prefer brightly-colored bars:

The largest discrepancies between Swing% and Zone% can lead to some silly swings and/or crushed pitches. After three straight balls, the hitter is said to be in the “catbird seat,” with a walk imminent. Yet, when they’re given the green light, the outcome can be a monster Marcus Semien home run:

And when hitters are most at the mercy of pitchers (on 1-2 counts is interestingly when Swing% most exceeds Zone%), you get Ramón Laureano swinging at a Tyler Glasnow slider about a foot in front of the plate (courtesy of Ben Clemens):

Clearly, count influences swing decisions, albeit sometimes in counterintuitive ways (Go Team Swing on 3-0!), and that is something I will have to control for if I want to understand the effects of other subconscious influences.

Swing-Mirroring Strikes Again

I limited my analysis of swings after swinging strikeouts to the first pitches of at-bats so that count would remain constant, Zone% would be close to 50%, and the influence of the previous at-bat would likely be at its peak. But, even when looking only at first pitch swing percentage (FPS%), the number of outs can skew results:

Given that the previous batter must (except in the rare, reached-first-after-a-dropped-third-strike case, of which there were 80 in 2021) have gotten out after a swinging strikeout, the number of outs in the post-swinging-strikeout condition will be systematically higher than in the post-other-outcomes condition. Nevertheless, FPS% was, to a statistically significant degree, higher after swinging strikeouts than after other outcomes when there were one or two outs:

Imitating Failure?

When I discovered that FPS% was higher when the previous hitter notched a base hit, even though home runs were the least influential in this regard, it made sense. Of course batters would be encouraged to swing when the swings of their teammates resulted in positive outcomes. And the lack of impact from home runs could be explained by a lack of urgency—after a home run, the bases are left empty, with no runs imminent.

But why would hitters be more likely to swing at the first pitch after a swinging strikeout, perhaps the most negative outcome from a momentum standpoint? The simplest explanation again lies with Solomon Asch and his 1951 conformity studies. Informational influence, likely the propellant of increases in FPS% after base hits, describes how in uncertain situations, a person will conform to their peers’ behavior when they believe their peers are more knowledgeable than them. A hitter might see their teammate as more knowledgeable about the pitcher (and I made sure my data did not span pitcher changes) after they reach base… but not after they go down swinging. This is where normative influence comes in. Normative influence describes a desire to conform even when it appears the group is wrong or unsuccessful, just because humans are wired to fit in.

Alternative Theory 1: Get In The Zone

You might be thinking, “hold on a second. We’re not just robots beholden to primitive subconscious heuristics… are we?” Well, let’s take a look at some other possible explanations for these results before we jump to that conclusion.

My first thought was that maybe the increases in post-strikeout FPS% were largely due to swinging strikeouts that occurred on pitches in the strike zone. After such strikeouts, the next batter could be thinking that, although their teammate couldn’t connect, the pitcher was at least throwing strikes. Consider this Andrew Velazquez punchout on a nothing-special four-seamer from Spencer Howard:

Could they make contact where their teammate couldn’t? It doesn’t look like they really tried. FPS% after in-zone swinging strikeouts was 32.3%, while FPS% after out-of-zone swinging strikeouts was 33.3%, and was not a statistically significant difference.

Alternative Theory 2: Bend Before You Break

Another thought I had was that maybe the majority of swinging strikeouts came on breaking balls, and the next hitter was hoping to jump on an early fastball to avoid a nasty offspeed pitch. While it’s true that the majority of swinging strikeouts (59.8% for which there was pitch-type data) came on breaking balls, it’s not true that these types of swinging K’s led to a higher FPS%. In fact, they led to a somewhat lower FPS% (at exactly p = .05, for the statistically inclined). After a swinging punchout on a breaking ball, the next hitter swung at the first pitch at a 32.4% clip. Yet, they swung at the first pitch at a 33.7% clip after a batter K’ed on a heater.

Since this effect was only marginally significant, the slightest change in one’s definition of “breaking ball” can render it negligible. For example, I initially considered cutters non-breaking balls. If they’re considered benders, the numbers change to 32.6% and 33.4%, respectively, and the result is entirely insignificant. In other words, take the following conclusion with a grain of salt. But if we are to postulate, my guess is that instead of hitters deliberately trying to avoid breakers by searching for a fastball early, they are still just subject to subconscious influences – seeing a strikeout on a fastball, they are primed to expect another fastball (even early in the count) and are thus more likely to swing.

Implications

“I guess we are just robots.” The computer-generated voice in your head says. Well, it’s important to note that, while batters do swing significantly more on the first pitch after a swinging strikeout, the effect isn’t all that large: FPS% comes in at either 1.6 or 2.3% higher depending on the number of outs. Recall from your intro stats class that for an effect to be statistically significant, all it needs to do is show up consistently across large sample sizes. It doesn’t necessarily have to have a huge impact, or “effect size.”

Additionally, some hitters have shown an ability to overcome this effect to a pretty impressive degree. There were 131 hitters who came to the plate at least 50 times after a swinging strikeout (not counting dropped third strikes with zero outs, of which there were only 19) in 2021. The top 10 trend-buckers are listed below in terms of the difference between FPS% after a swinging strikeout and FPS% after other outcomes. The latter FPS% excludes no-out situations since those were also excluded from the former.

This is a pretty eclectic mix, spanning Yuli Gurriel and his career year to Garrett Hampson and his 65 wRC+. The wide range of players might be explained by the fact that the “Difference” column does not correlate with first-pitch wOBA. Even if it doesn’t correlate yet, it may begin to correlate soon if pitchers were to pick up on this trend (as I previously detailed with the first-pitch approach after a base hit) and act on it, especially since higher FPS percentages also mean higher O-Swing percentages. Perhaps, this can be yet another way for pitchers to capture every little edge to optimize their approach.

Photo by Frank Jansky/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@JustParaDesigns on Twitter)