Last season, on the way to delivering 25-starts of 2.98 ERA ball and finishing second in the AL Rookie of the Year voting, Guardians’ right-hander Tanner Bibee got a lot from his four-seam fastball. He threw his ~95-mph heater for just more than 47% of his offerings, usually up in and above the strike zone, and it was among the most valuable 25 or so four-seamers in MLB by Statcast pitcher run value (+10).

Across his 11 starts to begin the 2024 season, it’s been a different story. Bibee’s overall results have been more solid than spectacular (3.99 ERA over 58.2 innings as of this writing) and the performance of his four-seamer has completely flipped. By run value, Bibee’s four-seamer has been the least valuable in MLB this season and has already accumulated a -13 run value.

To understand what’s changed on Bibee’s lead pitch and what he might need to do to fix it, we need to re-visit the development path that turned him into a consensus Top-100 prospect before last season.

Command is Foundational

The Guardians have a type when it comes to pitching prospects. Perhaps more than any other franchise, they target pitchers with command and the pitching acumen to succeed with average-ish raw stuff. Once they get these strike-throwing and pitch execution savants (often collegiate pitchers from smaller schools) into their development system, they work to build from that foundation and soup up their arsenals with more optimal pitch shapes, types, and the always beneficial increased velocity.

Where in the past, the adage was that “you can’t teach stuff” and many teams would seek to draft and acquire pitchers with untamed raw stuff and hope to teach them to throw strikes and how to pitch, today’s availability of data and technology has opened the door to the opposite approach. Cleveland has shown that you can teach stuff and those gains, combined with the foundational ability to command the zone and execute pitches, can create immense value.

Cleveland’s poster boy for this method might be Shane Bieber, a 2016 4th-round draft choice out of UC-Santa Barbara, whose low-90s heater and average breaking ball (at the time) had him projected as an up-and-down depth arm. A few years later Bieber won a Cy Young (and and finished another season fourth in the voting) while working in the mid-90s with multiple plus breaking pitches that tunneled together fabulously.

Shane Bieber, 94mph Fastball (foul) and 83mph Knuckle Curve (swinging K), Overlay. 😳😳

If you look up “Pitch Tunneling” in the PitchingNinja dictionary, this would be it. 👇 pic.twitter.com/a3vydABHpS

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) June 1, 2021

Bibee’s development has followed a similar trajectory. He was a 5th-round pick out of Cal-State Fullerton in 2021, well known (as Fullerton’s arms often are) for his command of an 88-92 mph fastball and feel for spin. At that time, Bibee was seen as a high-floor, low-upside starting depth prospect, but Cleveland had designs for him to be much more than that.

“When I first got drafted, they wanted me to separate my two breaking balls, they wanted me to get more ride on my fastball, and they wanted me to throw harder because I mean everybody throws harder nowadays,” Bibee said on MLB Radio last season.

On the first development task, Bibee prioritized his vertical-breaking slider among his two breaking balls, demoting his curveball to a “show-me” strike stealer. On the second and third development tasks, Bibee implemented some minor mechanical adjustments to clean up the efficiency of his movement and alter his stride direction so he wouldn’t land as closed off to the plate. Those tweaks helped his velocity jump and positively affected the shape of his fastball. He could stay behind the ball better on his fastball, which created more true backspin and brought more vertical riding action, instead of gyro spin and cutting movement that came when he worked across his body, as he discussed with FanGraphs’ David Laurila last season:

Bibee: “I would say it’s a pretty true fastball, or it can also be kind of more cutty. It kind of bounces between those two. I don’t get any run on it.”

Laurila: “Do you want it to cut, or would you ideally just get backspin and ride?”

Bibee: “Ideally ride. I mean, the cut doesn’t really matter to me as long as I can control it. If I get both of them, great. If I get one and can control it, great. But overall, I’m more searching for the ride and the command as opposed to cut.”

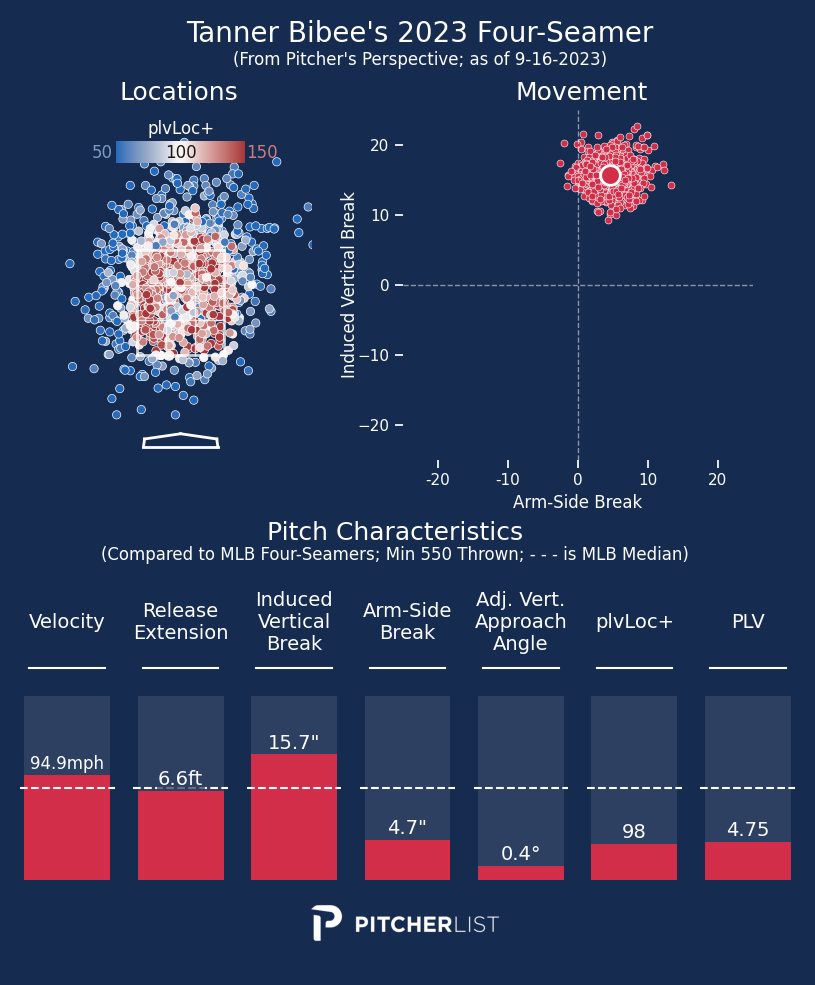

By the time Bibee made his big league debut in Cleveland last April, he was touching 99 mph and averaging better than 17 inches of induced vertical break with his fastball. Over his 25 rookie campaign starts, he averaged 94.9 mph and 15.7 inches of induced vertical break on his fastball, and his slider accumulated +8 runs of pitching run value and carried a 31.7% whiff rate.

While we often pay close attention to four-seam vertical shape and fall in love with outlier IVB and flat vertical attack angles, in Bibee’s case his 4.7 inches of arm-side (horizontal) break was just as notable. That’s not so much because he generated an impressive amount of run — you can see in the chart that it was well below the MLB median — but instead, because it represented an absence of the cutting (glove-side) movement that he was trying to avoid.

Cleveland gave him a clear and actionable development plan after he was drafted, and within two years, Bibee had checked off all their boxes and was producing at the game’s highest level. Moreover, he maintained his above-average strike-throwing ability, evidenced by his 7.7% walk rate (61st percentile) and 49.4% zone rate (a bit above the league’s 48.6% average). Consider the player development plan successful and Bibee another example of Cleveland raising the ceiling of an undervalued pitching prospect.

What’s Going On In 2024?

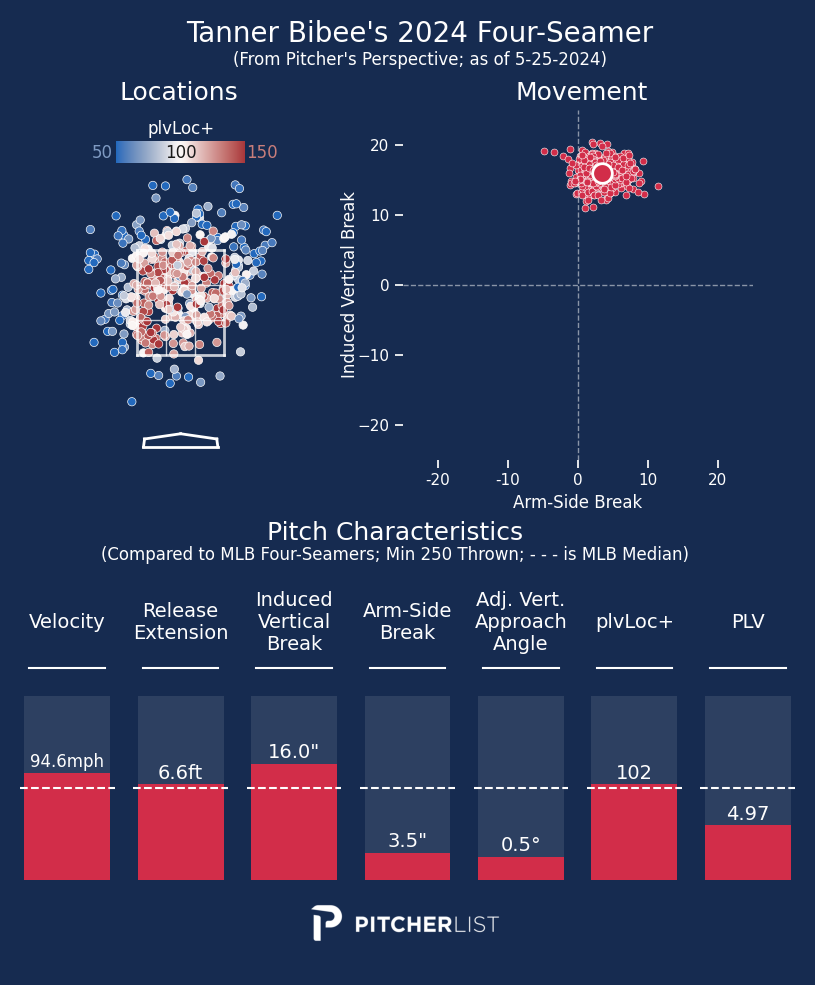

So what’s changed this season? I told you above his fastball has gone from a weapon to a major liability. Curiously, most of the usual characteristics we would check as potential causes of dramatically decreased effectiveness are more or less the same, and some are even improved. He’s averaging 94.6 mph in 2024, pretty much in line with last year. The average spin rate on his four-seamer has increased by about 70 rpm. You can see in the chart below that he’s getting a bit more IVB, the plvLoc+ score has improved, and his overall PLV grade on the four-seamer is better than last year.

The one aspect that stands out as different is the arm-side break, which is down 1.2 inches on average from last season. It’s a little difficult to see in the pitch movement plots above, but the 2024 blob of Bibee four-seamers has shifted subtly to the left (to his glove side). Whereas last season only 16 of Bibee’s 1,095 fastballs (1.5%) had glove-side break (i.e., were to the left of the zero line in the x-axis of the plot above), already 21 of 454 (4.6%) this season have moved glove-side. Similarly, 9.6% of Bibee’s four-seamers last season had 2 inches or less of arm-side break last year. This season that’s been 26% and that group of four-seamers have been hammered for .434 wOBA and -2.4 runs per 100 pitches.

On the flip side, only 11.5% of Bibee’s expresses have achieved 6 inches or more of arm-side run this season, which is less than half last season’s 25.5% rate. By run value, those more riding fastballs have also performed poorly (-2.9 per 100 pitches), but they also have a .313 wOBA that is right in line with last season’s .317 and are further supported by a .246 xwOBA and 25.9% whiff rate, which are both significantly better than last season. That might be an indication that Bibee’s 2024 results against his best fastballs have been somewhat unfortunate.

At any rate, that’s not the shape Bibee and the Guardians want his fastball to have, especially since he’s committed to leading with his heater. Again, from his discussion with Laurila:

Laurila: Was your pitch breakdown pretty much what we can expect going forward?

Bibee: “Ideally, I’ll throw a few more changeups. I also threw more sliders [40] than fastballs [36], and ideally I don’t really want that either. I had to lean on my slider a little bit because the command of my fastball wasn’t exactly there. Ideally, I’m throwing something like 50% fastballs, 25% sliders, 15 changeups, and the rest curveballs. Something in that vicinity.”

We know from Bibee’s comments referenced earlier that he’s seeking close to true backspin on his four-seamer. Perfect backspin would measure at 12:00 on a clock face, and Bibee’s riding four-seamers last season averaged a 12:30 spin direction, per Statcast. So far this season, that’s shifted subtly to 12:45 on average, which is moving away from his desired direction and probably contributing to the occasional cutting action and the lack of horizontal run.

Where that change in execution has been especially painful has been against left-handed batters, who have pummeled Bibee this season (.368 wOBA, up from .248 last year). I told you earlier his four-seamer has totaled -13 runs so far this season and (amazingly) all of that -13 has come against left-handers, who have produced .457 wOBA against his fastball this season. His four-seamer has been neutral against righties. A big chunk of that left-handed damage has come against the 26% of Bibee’s four-seamers that have that more cutting (or illusion of cutting) action. Those have been walloped to a .486 wOBA, -5.4 runs per 100 pitches, and drawn a whiff only 3.6% of the time lefties have hacked at them.

Bibee often targets up and away from lefties with his fastball, but when the pitch movement and execution are the opposite of intended, they can end up fat and in the middle of the plate, which is something Lance Brozdowski recently noted Bibee has been struggling with. You can see that change in the location plots below:

What Can Fix It?

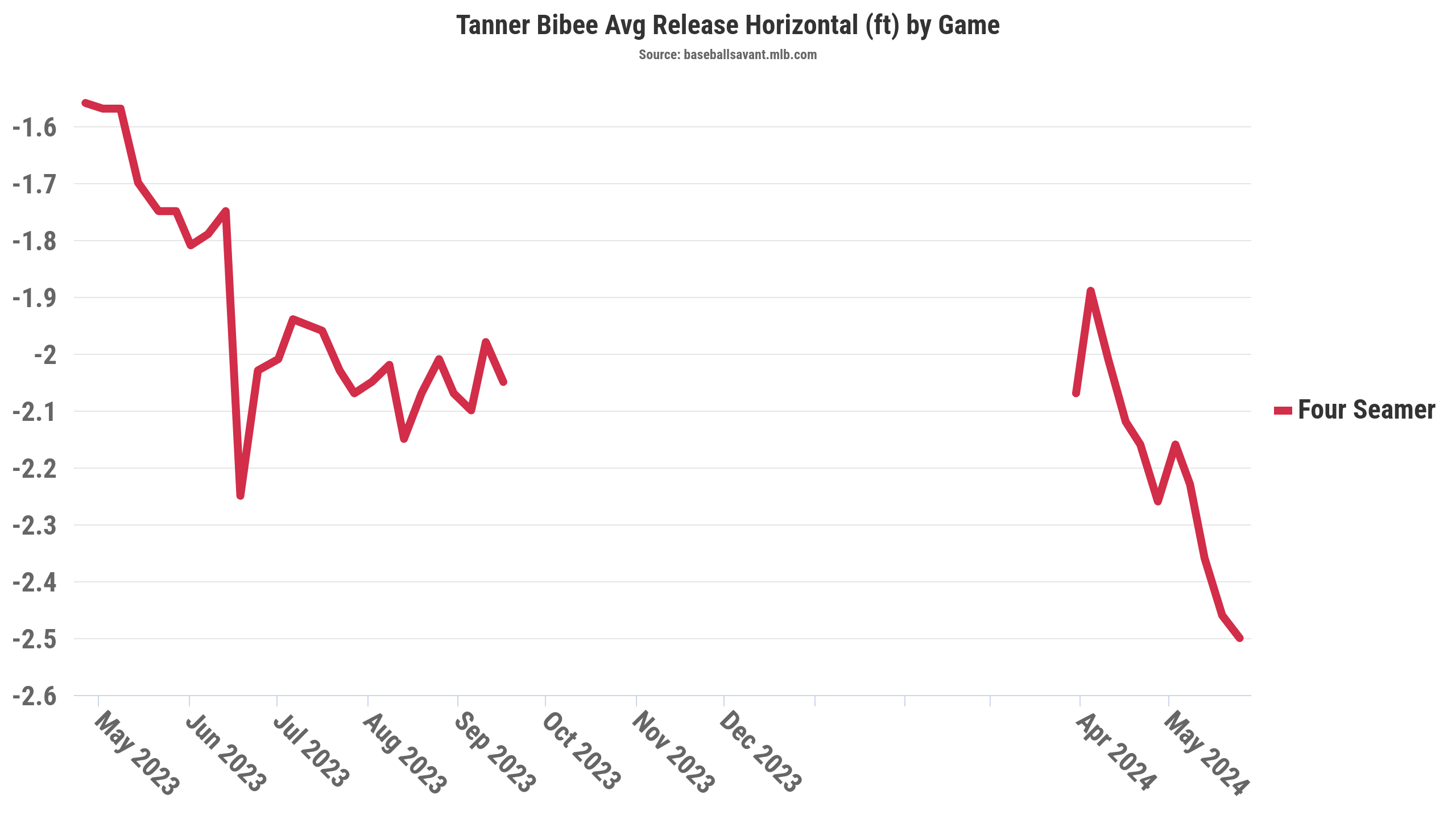

The good news is that this is something that Bibee has had to deal with before. Assuming there’s not some injury at play that’s causing him to alter his mechanics and repeat his release, it seems the fix here should be mechanical in nature. Recall the mechanical adjustments he implemented as a prospect to gain velocity and add ride to his fastball had to do with not landing as closed off to home plate.

For whatever reason, Bibee’s release point has drifted toward third base (i.e., closed off from home plate) as his MLB career has progressed:

You can see there that his 2024 work has come from several inches closer to third base than he operated last season. It’s not a coincidence that Bibee generated better than 17 inches of induced vertical break and more than 4 inches of arm-side movement on his four-seamer in each of his first 5 career starts, but has only managed to do that combination of vertical and horizontal movement in just 3 of his other 31 career outings. The steady move toward third base throughout 2024 thus far might indicate that he’s doing something deliberate, like a positioning change on the rubber pre-pitch. Intentional or not, it tracks with the spin and movement changes detailed earlier and sure seems to explain why he’s searching for his ride.

Zooming back out, Bibee’s development arc and 2024 growing pains serve as a useful reminder that pitching, even in today’s era of it sometimes being reduced to best velocity and stuff wins, remains a game of execution, as Greg Maddux often likes to say.

In the context of Bibee’s success last year, this year’s changes illustrate how fine the margins can be between the elite and the merely good. Those who reach the elite level and stay there are differentiated by the consistency of their execution. Bibee’s velocity and stuff gains since his prospect days have increased his potential such that he could be elite if he puts everything together and increased his margin for error if he doesn’t. His 3.99 ERA and 3.81 FIP this season attest to that.

In a way, he’s come full circle and is now back to needing to consistently execute his mechanics to achieve those optimal movements and locations. How well he does that will drive how much of that potential he’ll be able to reliably reach. But he’s not there yet, as Nick has cautioned previously. We’d all do well to consider Bibee (still just 25 years old) a work in progress who is still perfecting the adjustments he learned in the minor leagues.

Photos courtesy of Icon Sportswire

Adapted by Kurt Wasemiller (@kurtwasemiller on Twitter / @kurt_player02 on Instagram)