The Brewers already have two elite relievers in Josh Hader and Devin Williams. Hader has just posted two straight seasons of a sub-2.70 ERA and at least a 46% strikeout rate and Williams is coming off one of the best rookie relief seasons ever, where he posted a 0.33 ERA and struck out 53% of batters he faced. But what if a former starter turned reliever, over shadowed by the aforementioned in 2020, quietly showed elite ace potential? Insert Freddy Peralta.

Peralta made his MLB debut in 2018, where he pretty much exclusively started the games he pitched. He made 16 appearances, starting 14 games, and pitched to a 4.25 ERA with a 29.9% strikeout rate — not terrible! The following season he made eight starts in his first 12 appearances, but allowed 31 earned runs. Following an outing against the Houston Astros on June 11th, where he allowed six earned runs across four innings, Peralta was relieved of starting duties and sent to the bullpen. He still made one start in 2020, but it was his very first outing of the season (4 ER in 3.0 IP vs CHC).

Different Role, Different Results

| Innings | K% | BB% | ERA | FIP | xFIP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starter | 112.1 | 28.7% | 10.7% | 5.45 | 4.23 | 4.38 |

| Reliever | 80.1 | 34.7% | 10.9% | 3.59 | 3.02 | 3.68 |

When comparing his numbers, immediately we can see the difference in Peralta’s performance after coming out of the bullpen. When pitching in a relief role, he is striking out more batters and allowing a lot less runs. These numbers would not make him an ace-status reliever, probably just a solid one, but better results nonetheless. A large part of what makes Peralta interesting is the changes he underwent in 2020, so let’s use that as part of our comparison.

| Innings | K% | BB% | ERA | FIP | xFIP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 49.1 | 32.5% | 12.3% | 4.01 | 3.58 | 4.09 |

| 2020 | 26.1 | 40.0% | 9.1% | 3.08 | 2.20 | 2.83 |

Peralta’s 2020 improvements turned in some crazy good results. Among all qualified relievers, Peralta’s FIP and xFIP were the league’s 15th and 14th best marks, respectively. And if you want a Brewer frame of reference, Hader’s best single season FIP to date is 2.23 (albeit with more than three times the number of innings).

With respect to more “predictive” stats, Peralta saw massive improvements in xwOBA and xwOBAcon. His 2020 xwOBA dropped nearly 50 points, from .293 in 2019 to .249, and his xwOBAcon improved from .385 to .356. Peralta still allowed a barrel at a rate of 7.9% on the season, landing him in the 38th percentile, but his well-improved xBA and strikeout rate more than made up for it.

Lastly, Peralta’s 2020 pCRA of 3.16 put him in the 96th percentile of relief pitchers. That’s ranking in the top 4% in what is one of the most predictive ERA estimators we have for relief pitchers. This alone may already give him relief-ace status, but let’s go further into the strides Peralta took as a reliever.

Fastball Improvements

Perhaps Peralta’s biggest improvement came in the form of his four-seam fastball. Peralta’s fastball velocity is nothing more than average and his fastball spin, although in the 80th percentile, isn’t exactly elite. But the results speak for themselves.

| # Pitches | CSW% | Whiff% | PutAway% | xwOBA | xwOBAcon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 1243 | 29.8% | 29.5% | 22.1% | 0.325 | 0.409 |

| 2020 | 364 | 32.4% | 36.8% | 29.9% | 0.248 | 0.348 |

It’s the same trend we saw in his overall arsenal. Peralta is getting more strikes, a lot more whiffs, and a lot more strikeouts with his improved fastball. Plus, the results when contact is made improved too. Even his xBA on his fastball dropped to an impressive .188. Typically when we see an improvement like this, it stems from an intentional adjustment made. In the case of Peralta, I think his fastball got better because of two primary factors.

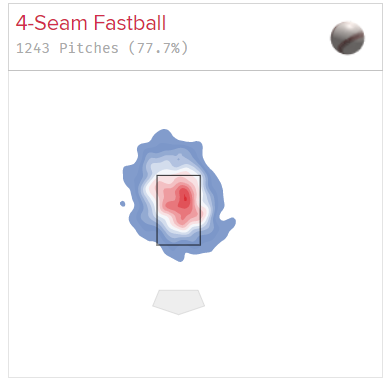

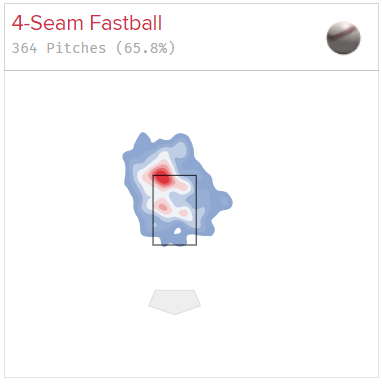

First, Peralta has made a big change in his fastball location over the last three seasons and it has helped him a ton. Take a look at how his hot spot moves over this span.

2018 FF Location

2019 FF Location

2020 FF Location

With each season Peralta’s fastball continues to move north. This change is a really good thing, but not for the reason you might think. Remember, Peralta has good-but-not-great spin on his fastball and he doesn’t have particularly great movement with it either.

His fastball’s vertical movement places him in the 73rd percentile and the horizontal movement puts him in the 22nd percentile. But Peralta does one thing exceptionally well; he gets a crazy amount of extension on his pitches.

Among all pitchers who threw at least 100 fastballs in 2020, Peralta averaged the fourth most extension on the pitch — 7.3 ft! The guys ahead of him – Tyler Glasnow, Brent Suter, and Brandon Workman – stand at 6’8″, 6’5″, and 6’4″, respectively. However, Peralta’s height is just 5’11”, which makes it even more abnormal that his release point is so far out in front of the mound.

How does this impact his fastball? Well, by intuition, the closer to the hitter a pitcher can release the ball the faster it is going to appear, regardless of actual velocity. This is something known as perceived velocity, because it’s how fast the ball looks to hitter.

But we will use an even better measurement to see this effect. Of the 330 pitchers who threw at least 100 fastballs this past season, Peralta had the fourth flattest VAA. VAA – or vertical approach angle – is the angle at which the ball approaches the plate. For someone who is throwing fastballs up in the zone, you’d want your VAA to be closer to zero, so it gives off the illusion of a pitch that rises.

A high spin rate is what can cause this effect for most pitchers, but for Peralta, it’s the pairing of a good spin rate and top-of-the-league extension. As a result, Peralta’s fastball grew more effective as he continued to throw it higher in the strike zone. If Peralta can continue to keep his fastball at the top of the zone, he is going to continue to get great whiffs and strikeouts with the pitch.

The Other Stuff

The second factor to his success is Peralta’s breaking pitch. Peralta’s curveball has always been one of his better pitches, but it has continued to improve each season. In 2020, the pitch posted a 36.4% CSW rate, a near 4% increase from his 2019 mark, and also held a 54.3% whiff rate.

Peralta doesn’t get great depth to his curve, but he does get about five inches of horizontal movement and a 13 MPH speed difference. Peralta’s curve last season graded out most similar to the 2019 curve of Jose Berrios and the 2018 slider of Mike Clevinger, which says Peralta’s curve is really more of a slurve, evident by the lack of verticality.

Furthermore, his curve’s -5.2 degree HAA, or horizontal approach angle, was the third largest approach angle among the 118 right-handers that threw at least 75 curveballs in 2020. This means that regardless of the amount of total horizontal movement, the angle at which it enters the zone is greater than most right-handed curves, and creates for a larger discrepancy between the perception of his pitches. Just take a look.

https://gfycat.com/faintwelloffizuthrush

In his first two seasons, his third pitch was technically a change-up, but he only threw it about 2% of the time, so it was a rarity. In 2020, he completely ditched the attempt for a change-up and replaced it with a slider. He only threw it 24 times, equaling 4.3% of his total pitches.

Its movement, velocity, and spin direction are all awfully similar to his curveball, so I’m not totally convinced that it isn’t just a misclassification of pitch type. However, almost every pitch database I looked at had it tracked to some degree, so I’ll buy it for now. Regardless, I don’t think Peralta needs a third pitch. If he can find another unique pitch, that’s great, but his fastball and curveball are already unique enough.

If one thing is for certain, it’s Peralta’s ability to miss bats and get strikes. He has two pitches with a CSW rate north of 30% and a uniqueness behind both pitches that can keep them effective. It’s hard to say whether or not these improvements would provide success for Peralta in a starters role, but in a relief role where hitters won’t see him more than once, they are can definitely play. Those two pitches alone are all he might need to evolve into an ace-level reliever.

Photos from Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)