Spencer Strider has arguably the best two-pitch combo in baseball.

It should be that simple, but in 2023, it wasn’t. Strider’s ERA jumped from 2.67 in his rookie year to 3.86 last year, fueled by his HR/9 jumping from 0.48 to 1.06 and an increase in BABIP. With most other peripherals staying the same and ERA estimators suggesting he was unlucky (2.85 FIP and 3.09 SIERA), it’s easy to suggest that a bounceback should be all but guaranteed.

But Strider’s reliance on just two pitches makes him vulnerable, no matter how good they are. As hitters continue to get more and more looks at him, it becomes easier to pick up on just two pitches. Strider has a changeup that he exclusively deploys to lefties, but only 12.5% of the time.

Deploying the pitch for righties (and bumping the usage on lefties) can help Strider solidify himself as the best pitcher in baseball, as it will give him multiple options to succeed later in games.

Attacking the Entire Strikezone

Although Strider’s two-pitch arsenal is as filthy as it gets, only having two pitches leaves some gaps in the strike zone. Filling up the entire strike zone makes hitters worry about multiple layers of pitch sequencing and it affects how they recognize different pitches. This is why pitchers with more pitches that move in all sorts of directions have a higher floor than those with fewer pitches because they are more unpredictable.

With Strider’s two pitches, a hitter can identify that a pitch down-and-away is a slider and an elevated pitch is a fastball. It’s slightly more nuanced than that, which I’ll get into, but a hitter seeing Strider a second or third time in a game gives them a better chance at pitch recognition having already seen his arsenal.

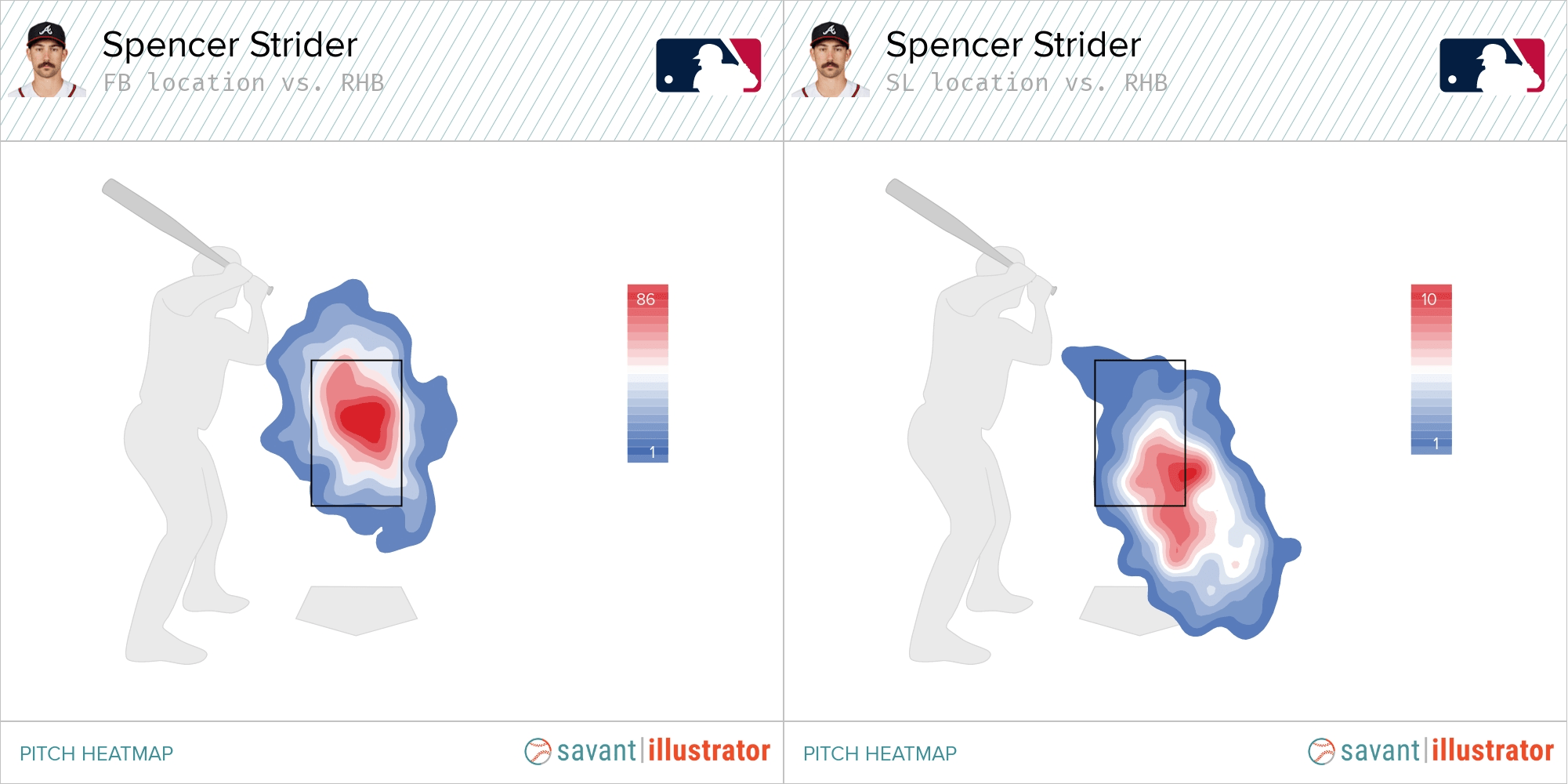

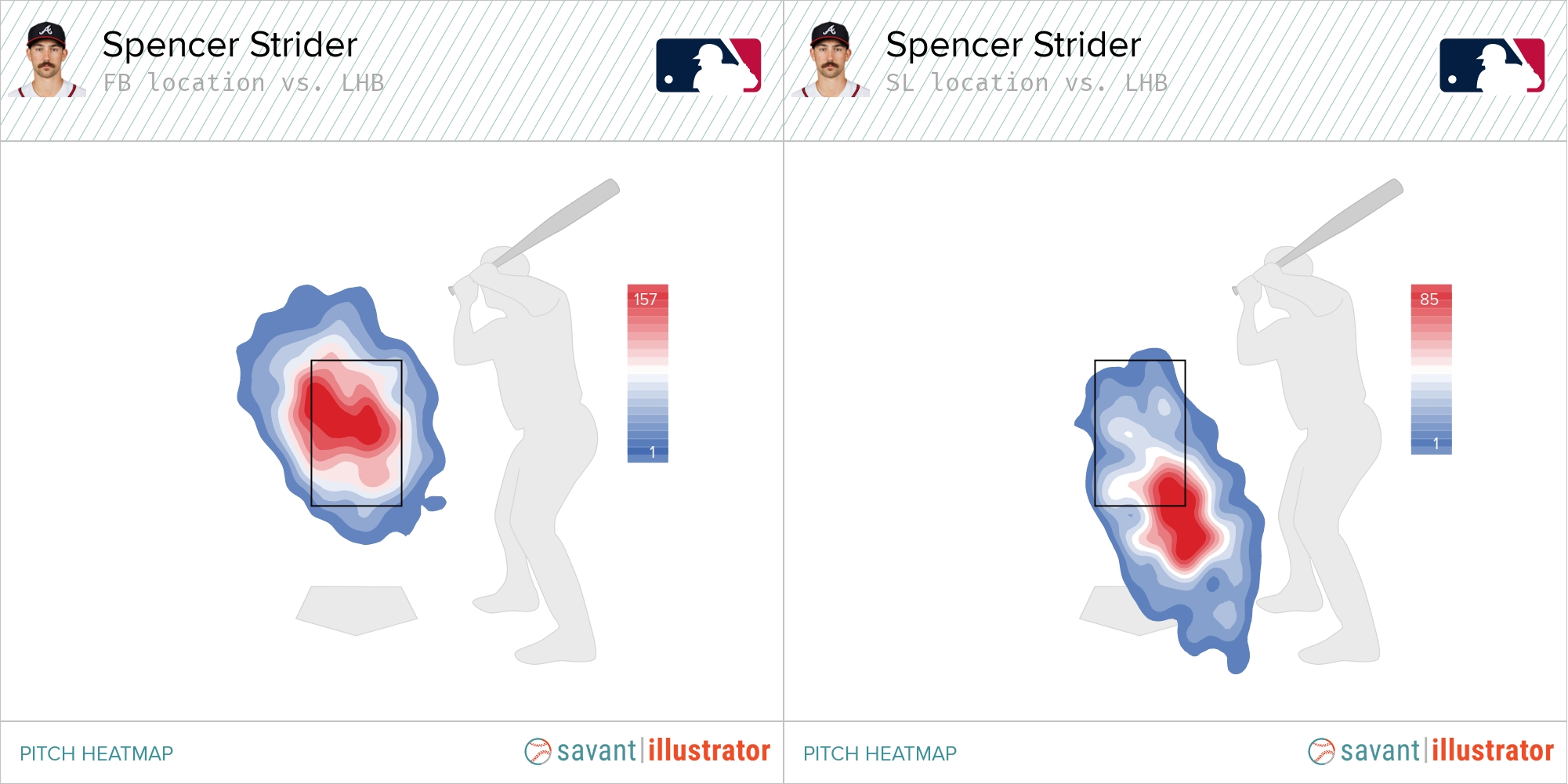

We’ll look at his plan of attack against both-handedness hitters to show how he has a gap down-and-arm side to both types of hitters.

Against right-handed hitters, Strider elevates his fastball over the center of the zone and occasionally goes up and in. The slider sometimes sneaks into the center of the zone, but it’s primarily down and away on the black. This leaves down-and-in to righties as a gap.

Against lefties, it’s a similar story: middle and up with the fastball and down-and-glove side with the slider. There are two small differences compared to RHB: the fastball is more up-and-away and the slider is more frequently out of the zone. Again, this leaves a down-and-arm side gap in his attack.

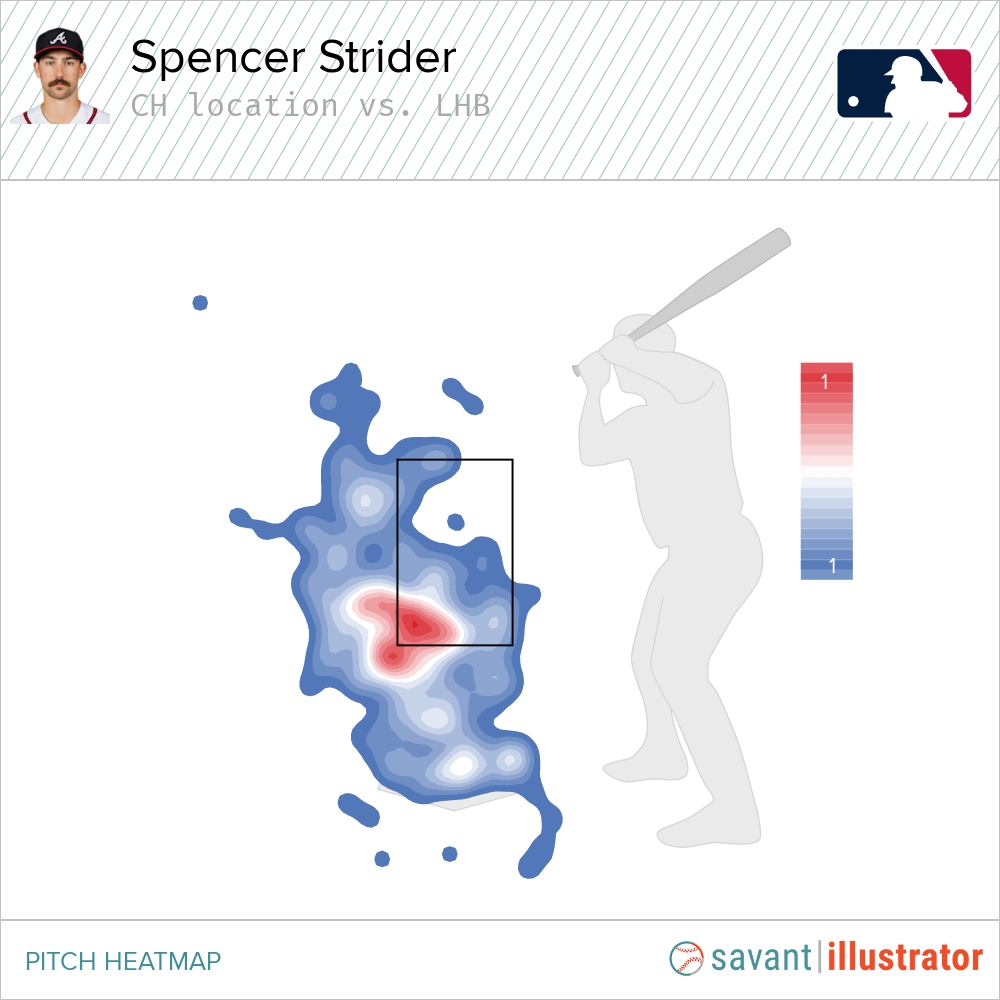

Enter the changeup: he uses it 12.5% of the time against lefties to actually fill that gap in the zone.

This is a good start, but his locations are inconsistent and he struggles to effectively get the pitch in the zone. The changeup has a 22.9% zone rate, which is in the 10th percentile for changeups.

However, he has shown that there is promise in the pitch. It has a 19.2% SwStr%, which is in the 83rd percentile, and a 23.3% ICR%, which is in the 95th percentile. It effectively can get whiffs and limit hard contact, but it lacks command. There’s legitimate potential in the changeup, but the low usage prevents it from reaching its full potential.

Usage and Times Thru Order (TTO) Penalty

With just two pitches, the changeup is the final piece to the puzzle. When hitters see Strider for a second or third time, it’s significantly easier to recognize what pitch is coming. This doesn’t only apply to Strider, but rather all pitchers: starters across the league perform worse each time the lineup turns over. However, Strider is hurt more by the fact that he mostly only has two pitches.

The most jarring aspect of these splits is the ERA, which jumps by an average of 1.44 from the first TTO to the second & third TTO. The HR/9 also jumps by exactly one home run from the first and third TTO, which is the other harsh increase for Strider as he goes through each TTO.

With his ERA being similar for the second and third times through the order, it appears that the approach changes between the two, but both are unsuccessful. Strider nibbles around the zone more in the second TTO, hence a higher walk rate and a lower HR/9. He goes back into the zone for the third TTO and gets hit harder, but doesn’t walk as many batters.

Looking at his pitch usage, Strider diversifies later in the game, but not in a drastically different way.

Against righties, Strider barely deviates from his fastball and slider usage, and only slightly incorporates the changeup for the third TTO. For lefties, he drops the fastball usage down the later he gets into the game and replaces that mostly with the changeup. As for the results on each of these pitches by TTO, the changes against righties are largely standard but against lefties is interesting.

For righties, the .026 increase in xwOBA is only .002 above league average, which is negligible. The slider increases .077, which is .027 more than the league average. For LHB, the fastball sees a decrease in xwOBA, which can be contrasted with a massive increase in the changeup’s xwOBA.

Throwing the changeup more often for the third time through the order allows Strider to be more successful on his best pitch. This can be extrapolated to more situations, where the third pitch makes hitters worry about more than an upper-90s fastball and a wipeout slider. One at-bat that makes me believe in Strider using the changeup more is this sequence against J.D. Martinez in May. Martinez had a 132 wRC+ against RHP last year, and he ranks 13th in wRC+ among all RHB against RHP since 2015 (min. 1000 PA).

In this at-bat, Strider goes fastball down, changeup down, and slider away, depositing the three-time Silver Slugger with ease.

Martinez is actually late on the 0-1 changeup, which gives Strider complete control of the at-bat. Strider then goes away with the slider and Martinez stands no chance. Adding more changeups against righties can keep the fastball and slider effective as he gets later in the game, he just needs to commit to it.

What Should the Change Be?

In conclusion, the changeup is crucial in maintaining success for Strider against lefties later in games. It helps increase the effectiveness of his two best pitches and can keep opposing hitters off guard. He’s flashed the changeup against righties rarely, which means he isn’t entirely opposed to throwing it against them.

If Strider could mimic the changeup usage for LHB he currently has for RHB, it would be a significant increase but not one that substantially takes away from the fastball & slider.

For lefties, I believe Strider could operate at 15% usage for first TTO but elevate to 25%-30% as he gets later in the game. These increases would hinge on his ability to throw more strikes with the changeup, but I believe a more intentional reliance on the changeup would help refine it into a better-commanded pitch. He’s one of the best pitchers in baseball, but he could reach a new level of dominance with these changes.

Photos by Joe Robbins/Icon Sportswire, David J. Griffin/Icon Sportswire, Design by Jackson Wallace