Defense doesn’t really get a bad rap; it’s more accurate to say it doesn’t get much of a rap at all. (Is that good or bad? I think I’d prefer no rap to a good rap?)

That is to say, defense gets lost in articles like these for two primary reasons. First, it’s not frequently part of our fake teams, so when we’re looking for “breakout” players and performance or skill gains, we’re not often interested in taking their defense into account unless it’s for positional eligibility. It’s too bad, but understandable. The game has become much more of a pitcher versus batter matchup, rather than its nine-against-one beginnings. Defensive plays, however, remain among the most exciting in the sport, and, I’d argue, the most ready-made for highlight reels and GIFs. The aesthetic enjoyment of a great defensive play I believe comes from its relatability. Most of us have never faced a 90 mph pitch nor hit the ball 300 feet — making a home run (or even a hit) unfathomably far away. On the other hand, most of us have thrown a ball. We intuitively understand how hard it is to make a throw so far from home plate, or to run full speed and dive for a catch.

The reason defense isn’t part of the fantasy baseball landscape (for the most part) is also the second reason we don’t often analyze defense — it’s notoriously difficult to measure.

Outs Above Average from Baseball Savant has made huge strides in our ability to measure defense. Baseball Prospectus’ Fielding Runs Above Average (FRAA) is essentially OAA without the batted ball data and has proven to be reliable as well.

All advanced defensive metrics are essentially created to solve for the original sin of quantifying defense: fielding percentage.

Errors, on their face, seem like a great way to measure defense. What plays did you make, and which ones should you have made? Humans, however, were astonished to learn in the 1980s for the first time that we can’t always believe our eyes (I apologize if this is how you’re finding out). The diving catch made by the center fielder maybe shouldn’t have been so difficult, if he got a better jump on the ball. The shortstop that bobbled the ball actually reached one that 90% of other fielders wouldn’t get to because he’s so adept at reading the ball off the bat and quick.

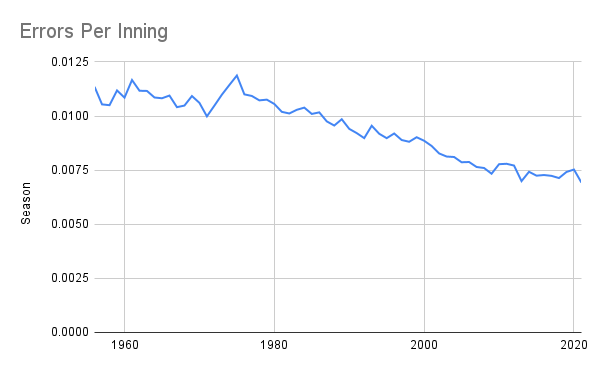

While errors may not be great measures of an individual’s performance in the field, in the aggregate they can offer clues as to what’s happening defensively. 2021, for example, is on pace to have the lowest number of errors in an entire season (save for shortened 2020, of course), as well as the lowest number of errors on a per-inning basis in history:

Errors, while an imperfect measure, are still a measure of something, or the trends would be likely randomly scattered throughout the graph above. Why are we seeing errors decrease steadily year over year, and what has led to 2021 being the “best” year for errors?

First, the obvious answer is that there are fewer opportunities for errors. That is, fewer balls are being put in play for which fielders can “err.” Balls in play have continued their decades-long decline, with 2021 on pace to become the lowest number of balls in play per game in history (again, aside from the 2020 season).

This is largely a function of increasing “three true outcomes” of homers, walks, and strikeouts, rather than defensive shifting, but that shift may be playing a role in the fewer number of errors, as well.

When the infield is shifted, two outcomes are seemingly more likely: the player hits the ball away from the shift, in which case no play would be made on the ball, or the ball is hit directly to a fielder (or at least, closer to the fielder than they otherwise would be in a standard infield alignment). Both outcomes reduce the possibility of errors, and that bears out in the numbers.

While standard defensive alignments make up 60.1% of plate appearances, they are responsible for 67.5% of errors in 2021. Those fielders obviously aren’t “worse” in standard alignment than they are in shifts, they’re just more likely to be credited (debited?) with an error.

The decline of balls in play and infield shifts are contributors to the decline in errors, but we would be remiss if not also acknowledging that players are probably also just getting better at defense year over year. It makes sense, as it’s certainly the case that human athletic performance consistently moves forward, regardless of the sport. I’ve written about how the Giants have seemingly “hacked” defense and improved at defense across the board. On an individual level, Nicky Lopez provides an instructive example of player improvement in defense.

Lopez leads all fielders with 19 Outs Above Average this year — it’s not unusual for a shortstop to be an adept fielder. But the magnitude of Lopez’s improvement has been astonishing.

Nicky Lopez OAA, 2019-2021

| Year | Position | Attempts | OAA |

| 2019 | SS | 124 | 2 |

| 2020 | SS | 16 | -2 |

| 2021 | SS | 521 | 18 |

Lopez has split time between second base and shortstop throughout his short career so far, and has largely been an average shortstop but above-average second baseman (9 OAA at second in 2020), but this year has played like the very best defensive shortstop in the league.

The Royals’ shortstop has seemingly improved the most at moving laterally to the third base side, recording 10 OAA this season compared to -3 in limited time in 2019.

https://gfycat.com/dearestgentleclumber

Lopez may be an example of an elite defensive shortstop coming into his own while getting more regular time at the position, but he’s clearly demonstrated marked improvement in his ability to react and go to his right for outs. The Giants’ aforementioned success at even improving their veterans’ defensive performance also suggests that the league’s development and progress needn’t just be limited to hitting and pitching, and along with fantastic young defenders like Nicky Lopez, that there’s plenty of room for take-your-breath-away defensive plays even as the opportunities for them slow.

Photo by Keith Gillett/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)

Another reason for a decline in errors: because errors are increasingly recognized as a poor way to measure defense (and less interest as well in ERA which is affected by errors), scorers may be less inclined to score plays as errors