Ever since I was a kid, I loved playing baseball video games. When I had an N64, it was Major League Baseball Featuring Ken Griffey Jr. (easily the catchiest title of any baseball video game).

Then, it was ESPN Baseball (RIP, loved the ESPN games) and the MLB 2K series before it all disappeared (because I’m an Xbox user. You know, like an idiot).

One of the things I used to do as a kid with these games would be to ask my dad to play with me. Since he could never really master the controls of the game, the way he’d play with me was by calling the game for me. I’d be pitching, and he would tell me what pitch to throw and where.

Throughout the many times we did this, there were a few cardinal rules of pitching that he taught me:

- Always establish your fastball with your first pitch.

- Never throw a curveball or slider high, because it will look like a mediocre fastball to the hitter and it will get destroyed.

Now, my dad never had any professional baseball experience, but he’s a lifelong baseball fan who’s read a ton about the sport and coached Little League for the better part of a decade, so he has a pretty solid base of knowledge surrounding the strategy of playing baseball.

But he’s not the only person to have told me those two rules for pitching. In fact, I’d argue they’re part of the generally-accepted wisdom of baseball that’s existed for a long time.

The thing is though, they’re wrong.

You Don’t Have To Throw A Fastball First

In fact, not only do you not have to throw a fastball first, there’s data that suggests you might not want to throw a fastball first. Why? Well, to answer that question, we should take a look at what hitters are most likely to do on first pitches.

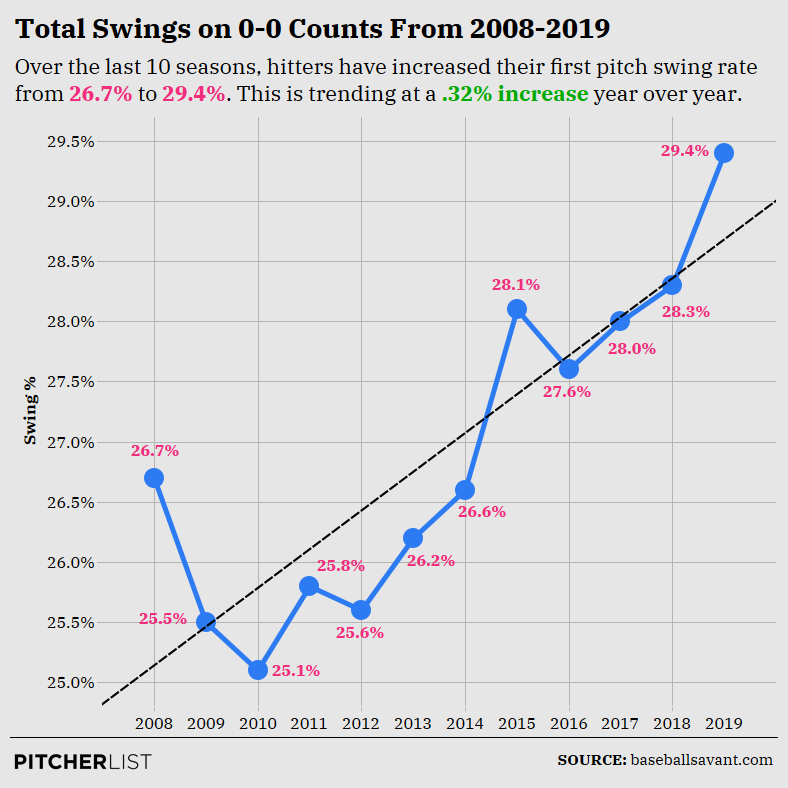

The answer? They’re swinging, as research from our own Alex Fast has shown.

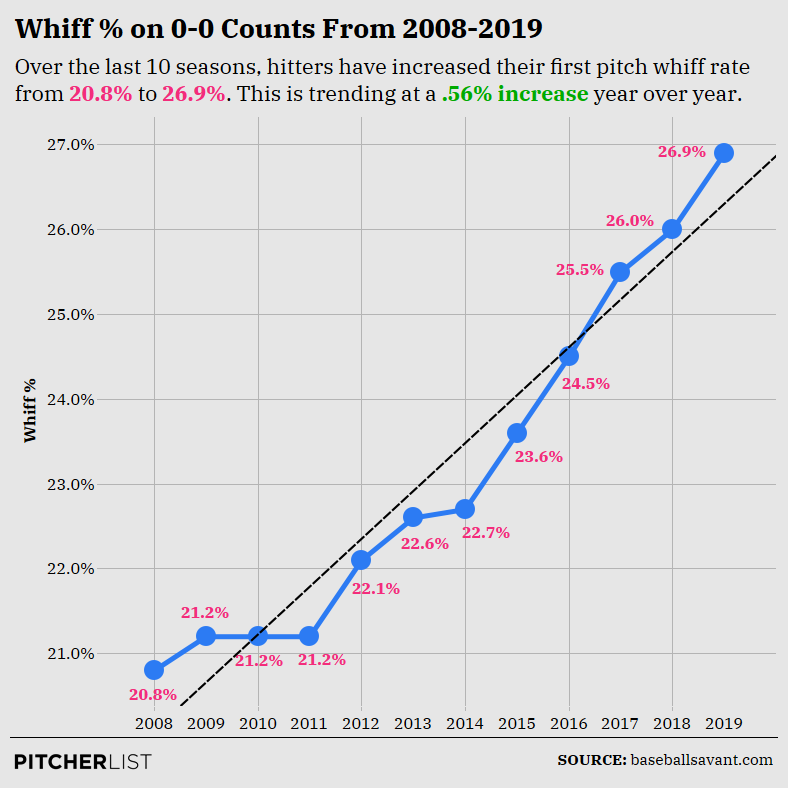

They’re also whiffing on the first pitch more than ever.

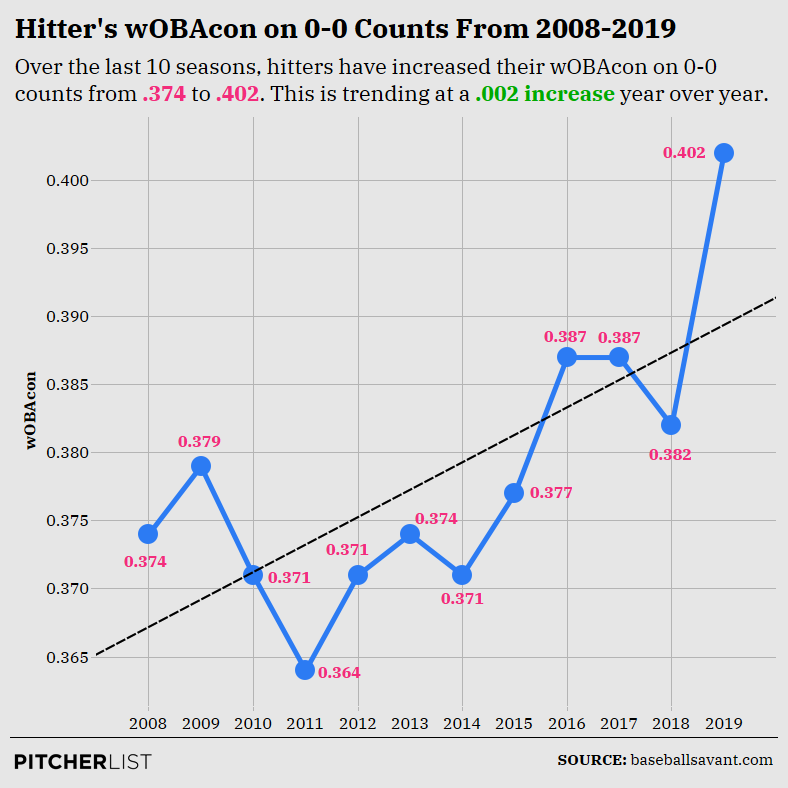

And if they do make contact on the first pitch, they’re having a lot of success.

Let’s review:

Hitters are:

- Swinging at the first pitch more than ever

- Hitting it better than ever

- Whiffing at it more than ever

So what pitch or pitches should you throw first? You might already have an idea where I’m going with this.

Here’s a look at data on different pitch types thrown in a 0-0 count from 2018-2020 (the columns are sortable, so feel free to play around with them):

| wOBA | ISO | wOBAcon | CSW | Called Strike | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastball | .403 | .261 | .385 | 37.8% | 32.0% |

| Curveball | .415 | .269 | .364 | 43.1% | 36.3% |

| Slider | .390 | .244 | .363 | 43.3% | 30.8% |

| Changeup | .362 | .230 | .398 | 35.1% | 23.1% |

| Cutter | .382 | .248 | .370 | 37.0% | 27.9% |

There are a couple of things that really jump out to me in that data. First, on 0-0 counts, curveballs and sliders have an exceptionally high CSW. Second, relatedly, they have those high CSWs because they have pretty high called strike rates.

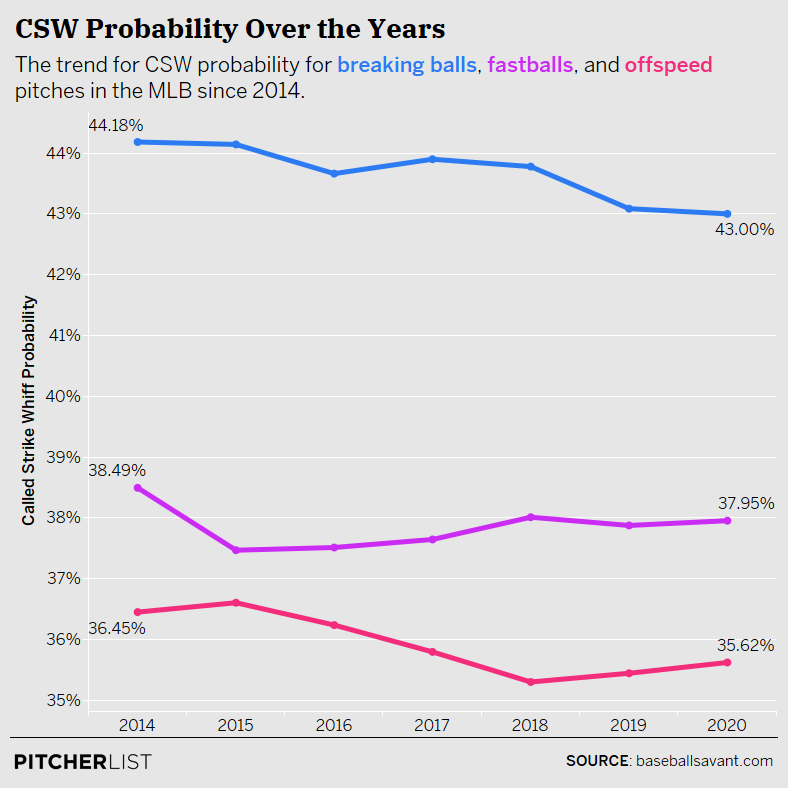

Those high CSW rates on breaking balls on the first pitch have held pretty steadily year-to-year too.

Data Visualization by @Kollauf on Twitter

Plus, the wOBA and ISO against for sliders and curveballs are pretty similar to fastballs. Sure, it’s high, but they’re all high, and with sliders and curveballs, you’re at least more likely to get a called strike.

Do you know what you’re also more likely to get with a curveball and a slider? A pitcher’s count. Here’s a look at all at-bats from 2018-2020 by their first pitch and the percentage of those at-bats that led to either a pitcher’s count (which we classified as 0-2, 1-2, and 2-2) and the percentage of them that led to a hitter’s count (2-0, 3-0, and 3-1).

| First Pitch | Total At-Bats | Pitcher’s Count Rate | Batter’s Count Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changeup | 32040 | 44.9% | 18.9% |

| Curveball | 56495 | 49.9% | 20.0% |

| Cutter | 25004 | 48.1% | 16.8% |

| Fastball | 253285 | 49.4% | 17.0% |

| Slider | 68648 | 51.0% | 17.3% |

For all at-bats that started with a slider, just over half ended up in a pitcher’s count, and just under half of those that started with a curveball ended up the same, both higher than fastballs (not by a ton, but still higher).

But wait! There’s more! Similar to the previous table, here’s a look at all at-bats from 2018-2020 by their first pitch and the percentage of at-bats that ended in a walk, strikeout, or being hit in play.

| First Pitch | Total At-Bats | Walk Rate | Strikeout Rate | In-Play Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changeup | 32040 | 9.0% | 19.8% | 71.3% |

| Curveball | 56495 | 9.2% | 24.0% | 67.2% |

| Cutter | 25004 | 8.0% | 22.9% | 69.6% |

| Fastball | 253285 | 8.0% | 23.1% | 68.9% |

| Slider | 68648 | 9.0% | 24.6% | 67.0% |

Unsurprisingly, since you’re more likely to end up in a pitcher’s count throwing a slider or curveball with the first pitch, you’re also more likely to have an at-bat end in a strikeout when you start it with a slider or curveball than you are with a fastball, and you’re less likely to end up with the ball in play.

Getting To An 0-1 Count Doesn’t Matter That Much

I know, that might sound insane, but honestly, getting to an 0-1 count as opposed to a 1-0 count doesn’t really matter all that much.

From 2018 to 2020, the league-wide wOBA on 0-0 counts was .397 and the league-wide ISO was .256.

On 1-0 counts? The league-wide wOBA was… .397 and the ISO was .266.

So basically, it doesn’t really matter if your first pitch is a ball, hitters are hitting just as well on an 0-0 count as they are on a 1-0 count, which essentially means an 0-0 count is a hitter’s count.

While that sounds more difficult for a pitcher, I think it’s actually good news if you want to throw a breaking ball on your first pitch, because if you throw it out of the zone, you’re way more likely to get a swing and a miss than if you throw a fastball.

From 2018-2020, the league-wide swinging strike rate on fastballs outside the strike zone on 0-0 counts was just 3.8%. On breaking balls? It was 11.4%. That’s a pretty big difference.

To answer what might be your next question, what count actually does matter, the answer to that is the 1-1 count.

Back in 2015, former closer Huston Street was quoted as saying the 1-1 count is “the most pivotal pitch in an at-bat,” and the numbers back him up. Here’s a look at the league-wide batting average, wOBA, and wOBAcon on different counts from 2015-2020:

| AVG | wOBA | wOBAcon | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-0 count | .345 | .393 | .387 |

| 1-0 count | .345 | .396 | .393 |

| 0-1 count | .325 | .357 | .350 |

| 1-1 count | .333 | .373 | .368 |

| 2-1 count | .342 | .389 | .386 |

| 2-0 count | .357 | .421 | .419 |

| 1-2 count | .162 | .179 | .337 |

My biggest takeaway from this data—there is absolutely no reason for a pitcher to lay a pitch in the strike zone on an 0-0 count just to get a strike and “get ahead 0-1.” The risk doesn’t justify the upside. But getting that 1-2 count is extremely important.

—

We’ve gone through about 1,000 words on first-pitch breakers, so let’s sum it up.

On the first pitch, compared to fastballs, breaking balls are:

- More likely to lead to a called strike

- More likely to lead to a pitcher’s count

- More likely to lead to a swing and miss if thrown outside the strike zone

- More likely to lead to an at-bat ending in a strikeout

- Hit just about as well as fastballs when contact is made

Now, in looking at some of these tables, you may have noticed that a lot of the percentages are really close together, and you might be thinking “yeah, sure, you’re ‘more likely’ for a certain outcome to happen, but the difference between a fastball and a breaking ball is really small.”

And you’re absolutely right. And that’s kind of the point.

I’m not suggesting that throwing a breaking ball on the first pitch is significantly better than throwing a fastball on the first pitch. Instead, I’m saying that throwing a breaking ball on the first pitch isn’t significantly worse than throwing a fastball, and, in many cases, it’s slightly better.

To summarize the summary, the data appears to suggest that throwing a breaking ball on the first pitch has very little downside and a decent amount of upside.

It’s Okay To Throw A High Breaking Ball

The other myth about breaking balls I’d like to break—you can throw a breaking ball high in the zone. In fact, you probably should. Why? Because it produces pretty excellent results.

Here’s a look at pitches thrown high in the zone from 2018-2020:

| CSW | Called Strike | SwStr | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fastball | 36.9% | 19.9% | 17.0% |

| Curveball | 60.3% | 56.0% | 0.4% |

| Slider | 51.4% | 39.1% | 13.0% |

| Changeup | 42.8% | 33.6% | 0.9% |

| Cutter | 42.5% | 26.8% | 15.7% |

What’s the first thing you notice? For me, it’s the absolutely absurd CSW that curveballs and sliders have. And there’s a good reason they have such a high CSW—they’re not being swung at.

Curveballs have a 60.3% CSW mostly because they have a 56.0% called strike rate and just a 0.4% swinging-strike rate, which is pretty wild to me. My guess is that batters are surprised by a high curveball, think it’s a mistake, or just going to be out of the zone, and wait on the pitch as it drops into the strike zone.

“Well that’s cool and all,” you might say, “but what about when a hitter does make contact?”

That’s a great question. Because per the conventional wisdom, a high breaking ball is likely to be crushed if a hitter makes contact because it’s going to be easier for the batter to see.

But the data suggests that’s not actually the case.

| wOBA | ISO | wOBAcon | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fastball | .303 | .210 | .385 |

| Curveball | .263 | .175 | .364 |

| Slider | .263 | .188 | .363 |

| Changeup | .342 | .262 | .398 |

| Cutter | .292 | .182 | .370 |

First off, it’s worth noting that clearly there is a bit of conventional pitching wisdom that holds true—don’t throw a changeup high in the zone, and there are plenty of pitchers who still hold to that philosophy, as it seems they should.

But, from 2018-2020, the second-highest wOBAcon, ISO, and wOBA on pitches high in the zone belongs to…fastballs!

So even if the ball does get hit, you’re still likely to get a weaker-hit ball throwing a curveball or slider high in the zone than a fastball. And on top of that, as we previously learned, you’re way more likely to get a strike.

Now, let’s say you’re a pitcher and you’ve got two strikes on a batter. If you’re going to throw a breaking ball, where are you going to throw it? Probably low in the zone, right?

Turns out, throwing a breaking ball high in the zone with two strikes might actually be a better idea, whether they make contact or not.

| wOBA | ISO | wOBAcon | CSW | Called Strike | Swinging Strike | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High zone | .188 | .128 | .347 | 29.6% | 15.2% | 14.4% |

| Low zone | .227 | .133 | .367 | 25.0% | 6.4% | 18.2% |

Breaking balls thrown high in the zone in two-strike counts are hit weaker and have better CSW and called strike rates than those thrown low in the zone. It’s not a difference of night and day, but it’s notable, and it certainly shows that you don’t have to avoid throwing a breaking ball high in the zone, even in two-strike counts. In fact, it might actually help you.

There is one thing I should note here—throwing a breaking ball in the top of the zone is a pretty high risk/high reward strategy. As we’ve seen, it can work really really well, but it’s also important to remember the mechanics of throwing a breaking ball like a curveball or a slider (especially a curveball).

Your command has to be very good to hit the top of the strike zone. Too low, and you risk a breaker right over the middle of the plate.

Throwing in the bottom of the zone is a bit more forgiving to breaking balls. We’ve all seen guys who lose command of their curveball or slider on a low pitch and it bounces in the dirt but still gets a whiff. If you do the same thing with a high curveball and you lose command of it and it drops a little bit too much, it’s probably going to get annihilated.

We Should Be Thinking About Breaking Balls Differently

I think if there’s anything to take away from all of this data, it’s that we should be thinking about breaking balls differently than we have in the past. That old conventional wisdom my dad taught me about breaking balls when I was a kid? Looks like it’s not as wise as we thought.

If there’s one thing I’ve been preaching when it comes to breaking balls, it’s throwing them more. I can’t tell you how many major league pitchers I’ve seen who have a great breaking pitch, sometimes two, and a terrible fastball, and their most-thrown pitch is their fastball.

Fortunately, I think we’re seeing more and more pitchers embrace this way of thinking, a style of pitching referred to as “pitching backwards.” Guys like Charlie Morton, Patrick Corbin, and others are making their most-thrown pitch a breaking ball. Why? Because it’s effective.

And I think this data supports that approach even more. A breaking ball isn’t just a supporting pitch in a pitcher’s arsenal anymore. It’s not the secret weapon wipeout pitch that a pitcher hopes he gets to use by getting a hitter to two strikes.

Instead, that curveball, that slider, it can be a pitcher’s primary pitch. The one they go to in an 0-0 count, the one they go to with two strikes, pretty much whenever.

And, even better, they have more flexibility with those breaking balls than we may have previously thought. If you’ve got an awesome slider, you don’t have to keep throwing it low. You can, it certainly can be effective, but you don’t have to, because it’s pretty effective up in the zone too.

That added flexibility can make pitchers even more effective. I’ve always been a proponent of what we here at Pitcher List refer to as the BSB (the Blake Snell Blueprint) in which a pitcher focuses on changing a hitter’s eye-level pretty frequently.

Now, in the BSB, you’re typically talking about fastballs high, breakers low, but this data shows you don’t have to do that. Want to throw a high curveball and then a low slider? Go for it. High slider and then a low fastball? Sure.

Pitching backwards typically refers to guys who throw their secondary pitches more than their fastballs, but I think the data supports pitching even more backwards—going breakers high and fastballs low (though again, you don’t have to do that, low breakers can obviously still be good).

The point of all this is not to say we should stop doing something, it’s more to say we should expand our thinking of what constitutes effective pitching.

Effective pitching is all about keeping hitters off-balance. The less predictable you are, the more effective you’re likely to be as a pitcher. It’s my belief that doing something like throwing a high breaking pitch is likely to produce a called strike because they’re not predictable, hitters aren’t expecting them.

In other words, it keeps them off-balance.

And just like life, that’s what baseball is about—balance.

I’d like to issue a huge thank you to Justin Filteau from our data science department who helped out massively with the research inside this article. Justin rocks.

Graphic by Michael Packard/Data visualizations by Nick Kollauf (@Kollauf on Twitter)

Pitching backwards may be the most overlooked path for SP’s to resurrect/extend their career. When you review James Shields career, it’s clear. The real question for any SP with strong control of their “secondary” pitches: Why not make pitching backwards at least a mandatory variance on second/third times through an order?

If you wanted to further this piece, I would encourage you to research statistics on breaking balls in the top ninth of the zone, instead of just the top third. I think you’ll find exactly what you expect — pitches in the top ninth are exceptionally difficult to hit, the top eighth easier, the top seventh easy. Does it have practical application? Maybe not. Is it interesting? For sure.

Peter

Totally agree especially relative to your thoughts on “overhanging” breaking balls. Ask Rich Hill. I have the data backing that up from Ken Kendrena at Inside Edge.

In respect to 1-1,strikes, when you throw 1st pitch strikes, your chances of throwing two strikes before you throw two balls is greatly enhanced. The biggest swing pitch relative to OPS is the 2-1 pitch.(2-0 second & 1-1 3rd.) With that being said, getting to two strikes as fast as possible is important considering the low two strike offensive stats.

jw