When Dylan Cease starts on Tuesday against Minnesota, there’s a decent enough chance he makes me and this article look pretty bad. Despite velocity and stuff that most pitchers can only dream of, he’s been one of the most inconsistent and frustrating pitchers in the majors since he made his debut (with yours truly in attendance) in July 2019. Before his last two starts, coming against Detroit and Cincinnati respectively, Cease had never once in his career recorded back-to-back starts of zero earned runs. In fact, the first of those two starts snapped a 13-start earned run streak, making for his first scoreless start since Aug. 7, 2020. Not quite what one would hope from a consensus top-ten pitching prospect!

Anticipation for his 2021 was high after multiple offseason reports (and videos) of mechanical tune-ups with new pitching coach Ethan Katz, but in the early going, little seemed to have changed — before those last two starts. Reading anything into two starts is by definition an overreaction, but the suddenly-elite outputs raise an eyebrow. 13 IP, four hits, and 20 strikeouts are all career-best outputs over a two-start stretch. Game scores of 84 and 78 are literally the two highest of his career. Given the scouting report and projections on Cease — there’s a high chance everything doesn’t come together, but if it clicks, it’s gonna click — it’s worth taking a peek to see if he might be turning the corner.

Before we get to what’s going good, let’s start with the bad and obvious. Two starts are two starts, and the extended record is much worse. Dating back to last season, Cease has walked three or more hitters in seven of his last nine starts. He’s still walked 12% of opposing hitters in 2021, one of the ten worst marks in the league. He’s throwing just 2% more of his pitches in the strike zone this year than last year, so given that he walked exactly three in his first four (and sixth!) starts of the season, there’s an initial outward appearance that it’s more or less the same story.

Trust me, I know what it’s like. I attended Cease’s April 11 start against Kansas City at Guaranteed Rate Field. He went to a two- or three-ball count against 12 of the 19 batters he faced. The weather was cold, and I was a tiny bit underdressed. The 4th inning took 50 minutes. Nothing short of torturous.

At the same time, the results are there, with those last two starts doing wonders for his overall statline. Ben Clemens and Justin Choi both wrote last year on the numerous ways Cease was simply getting lucky with his run prevention, but peripherals suggest that his 2.56 ERA this season has been much more earned than his deceptively strong start to 2020, when he posted a 3.20 ERA but 5.82 FIP through his first ten starts before falling apart to end the season. The most obvious culprit is the return of the strikeouts that mysteriously disappeared last season:

| Year | G | IP | ERA | BB% | K% | wOBA | xwOBA | FIP | xFIP | SIERA | xERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 12 | 58.1 | 4.01 | 13.3 | 17.3 | .357 | .388 | 6.36 | 5.87 | 5.86 | 6.87 |

| 2021 | 6 | 30 | 2.37 | 12.0 | 32.0 | .263 | .287 | 2.81 | 3.59 | 3.70 | 3.04 |

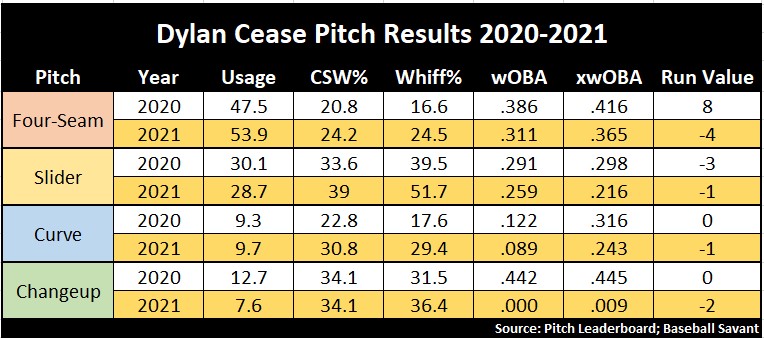

The most obvious culprit for that, meanwhile, is an across-the-board improvement on his secondary pitches, all three of which have been nothing short of elite after mediocre results last season:

Cease’s slider and curve are both nasty enough pitches that we don’t really need to ask how he’s getting those numbers. This is more or less what I picture when I think about a 50% whiff rate slider:

And even though the curve doesn’t quite rack up whiffs like its counterpart, it’s easy to see why nobody’s been able to square it up when they do make contact:

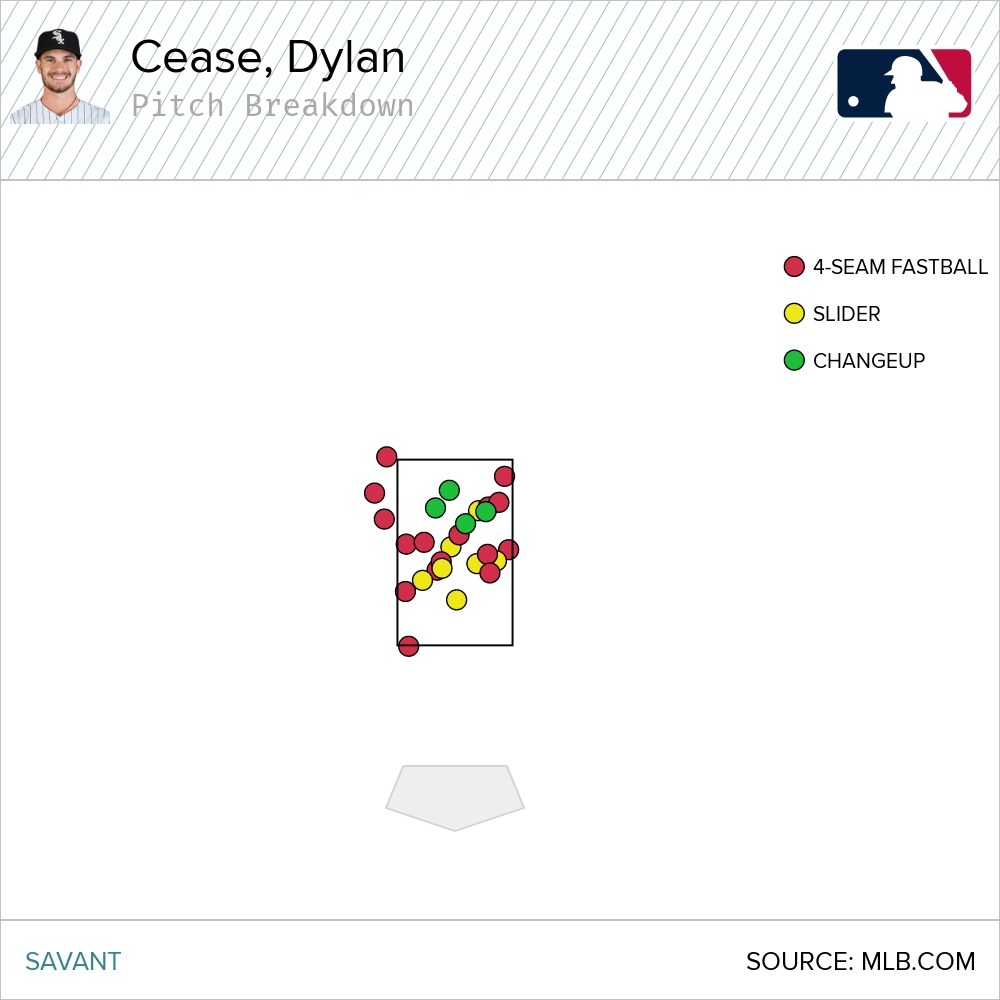

So, the eye test and the ratio stats both make it look like it’s those breaking balls doing most of the legwork when it comes to that across-the-board improvement, along with a less-is-more approach on the changeup, which was effective in 2019 before getting hammered last season.

On a technical level, that is true — it’s the breaking balls that are drawing most of the third strikes that weren’t there in 2020. 67.5% of Cease’s strikeouts this year have come on non-fastballs, a rate up more than 15% from last season, and ranking 22nd out of 104 starters with 25+ strikeouts in 2021. Meanwhile, in spite of its improved results, batted-ball and CSW numbers still see his four-seamer as a below-average pitch.

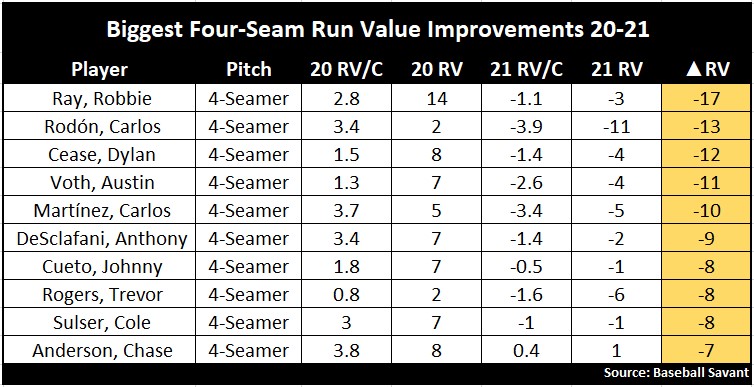

That also might be giving a little too much credit to the rate stats. If you look at the last column on that second chart, you’ll see that the most dramatic turnaround in terms of cumulative value has come from the four-seamers, which has already totaled a -4 run value according to Statcast, meaning it’s essentially prevented four more runs than an ordinary fastball. Last year, that total was +8, one of the worst marks in the majors. That 12-run turnaround is more than just a big swing; it makes it one of the most improved four-seamers in the big leagues this year, going off pure results:

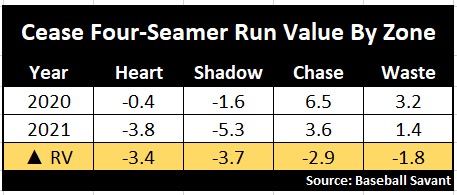

In a nutshell, that’s a list of fastballs that are not only somewhat improved, but are actively getting outs this year after being lit up a year ago. Breaking the zone down into different sections, there’s no single location where this improvement is happening, either. The pitch is simply more effective in every place it’s being thrown:

This is interesting because it implies that Cease’s fastball has been getting positive results on a pitch-by-pitch basis in a way that’s not quite being reflected in the rate stats we typically use. A .311 wOBA is good for a four-seamer, but not that good, and both that and its 24% CSW are still the worst marks among the 32 four-seamers with a -4 run value or better so far this year. What’s going on?

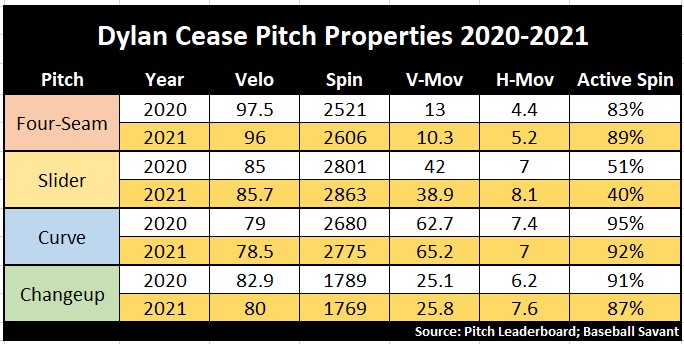

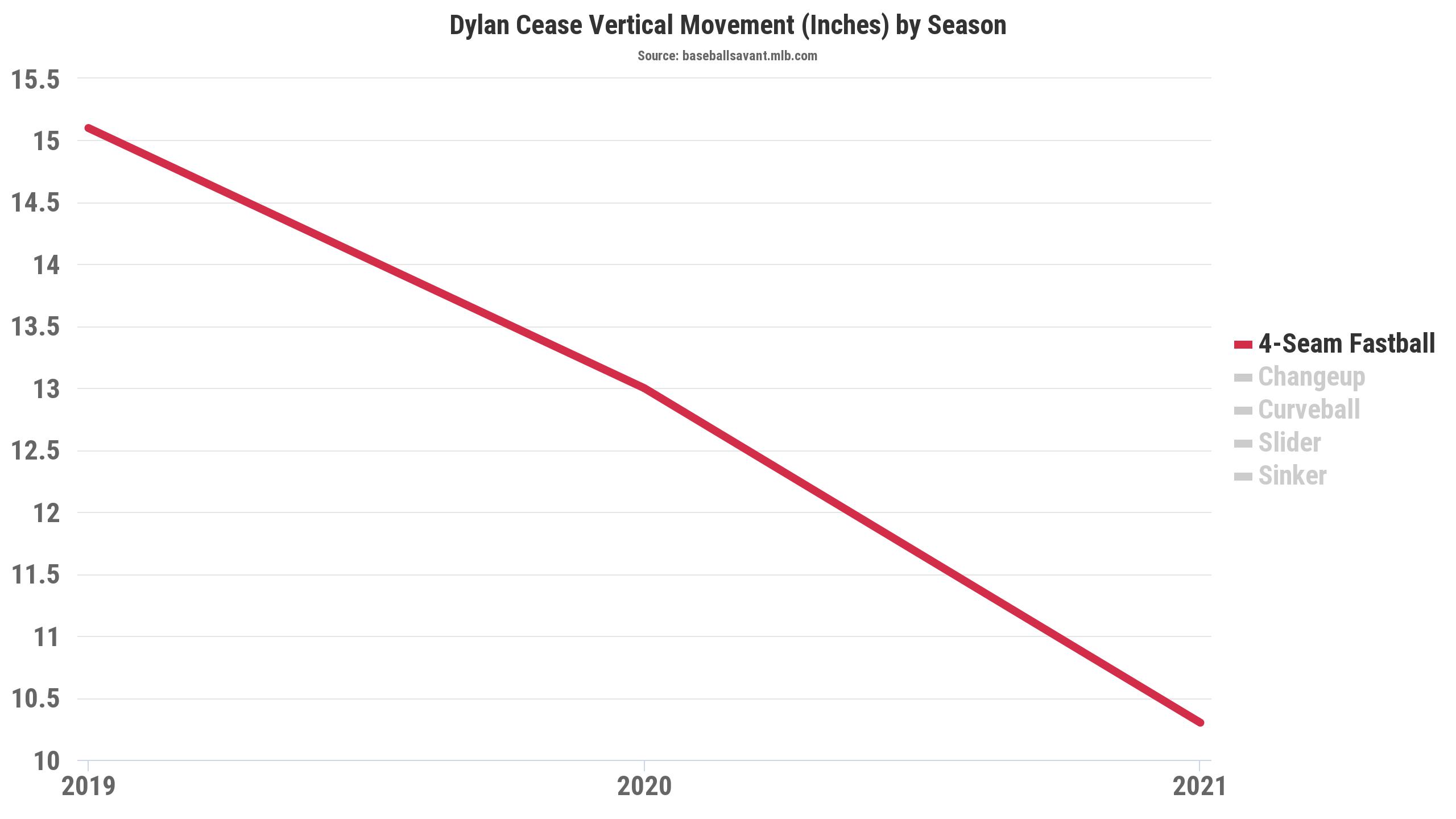

Naturally, when we see a pitch getting drastically different results, the first conventional step in investigating is to look at spin and movement, and see if there’s something different about the pitch itself. This is where the fastball sticks out among Cease’s other improvements. In terms of velocity and shape, his curveball and changeup are more or less the same as ever, but he’s made noticeable tweaks to how he’s spinning his fastball and slider:

The adjustment to the slider is small, but seems like it’s working positively. It might be getting better separation from the curve by adding an inch of side-to-side movement at the expense of a few inches of up-down movement, while the curve simultaneously added a couple inches of drop in the other direction. Perhaps relatedly, he appears to be putting more gyro on the slider, cutting down the active spin by 10% while actually adding a tiny bit of velocity. Basically, by spinning it a bit more like a football than a fastball, Cease has made the pitch a touch sharper than it was before, if such an imprecise descriptor makes sense here. None of that is good or bad per sé, but it seems to be working well with the numerous other small adjustments he’s made.

Gyro and active spin are also where the four-seamer stands out, and considerably more than the slider, to my eyes, and it’s also one thing that might be helping him get more value out of the pitch. Brian Menendez already covered some of this recently for Beyond the Box Score, and it’s worth taking a slightly deeper look. I’m a visual-learning type of dude, so here’s a visual representation of what I think is the most important column in that chart up there:

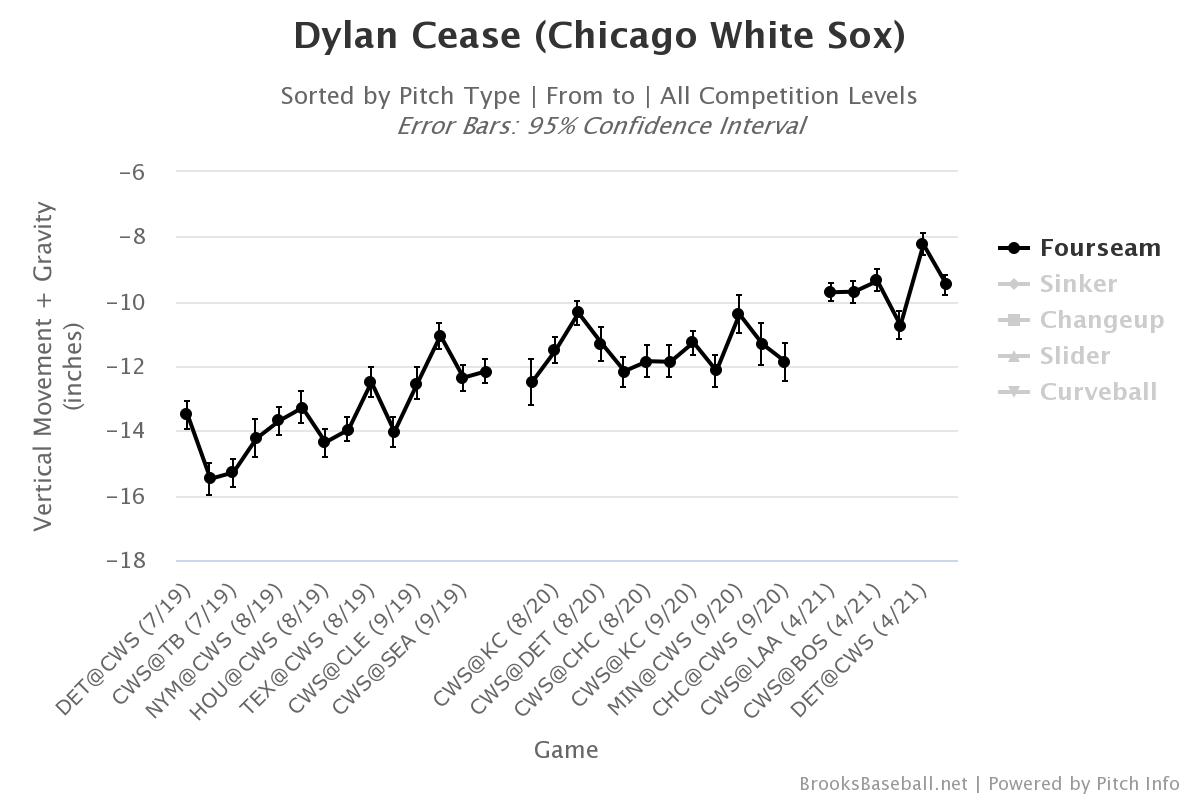

Not only is his vertical movement at an all-time low on the year — and remember, less movement means more “rise” — it’s steadily risen as the year has gone on, culminating in his last several starts:

When he entered the league, Cease cut his fastball more than almost any other starter, meaning he was one of the worst in the game at throwing a “rising” fastball that turns backspin into “movement.” This was the point of Clemens’ article last year, and it was his explanation for why Cease’s four-seamer just wasn’t missing any bats last year, in spite of its top-shelf velocity and spin.

That’s all changed in 2021. Now, with his active spin near 90% — not great, but much closer to average than the bottom ten — he’s getting a full three more inches of carry on the four-seamer than he did last year, and despite losing 1.5 mph on its average velocity, its spin rate is up by roughly 75 RPM, a development sure to raise some eyebrows. Regardless, it explains where the uptick in whiffs is coming from — by both adding raw spin and fixing his active spin at the same time, Cease essentially followed the Betty Crocker recipe for a new-age zippy four-seamer at the top of the zone.

It’s not all sunshine and butterflies, though. Run value is a hugely flawed stat, and the improvement isn’t being reflected in CSW or xwOBA because, again, his control is still bad. He still throws a lot of non-competitive pitches (more on that in a sec), and he’s also one of the league leaders in getting pitches in the zone called balls, ranking second in the league this year with nearly 8% of his pitches in the zone being called for balls. That might not be about luck as much as one would expect. A lot of it is certainly randomness that may self-correct eventually, but it’s also what happens when you miss a lot of spots and make the catcher come across the plate to frame a fastball. Most pitchers aren’t getting a called strike when they miss like this, and Cease misses like this enough to give a catcher anxiety:

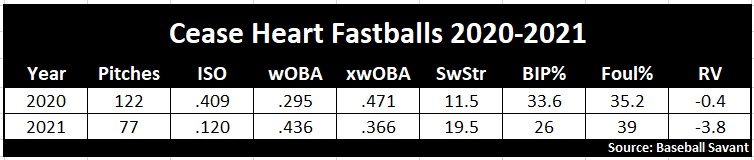

All of this is to say, however, that now, with a true riding fastball in the upper-nineties, when Cease does stay in the vicinity of his spot, hitters can’t really do anything with it. All of that run value gained in the heart and shadow zones is a result of hitters missing or mishitting pitches that they were squaring up last year. The difference on fastballs over the Statcast-defined “heart” of the plate — i.e., right down the middle — from last year to the present tells a good part of the story:

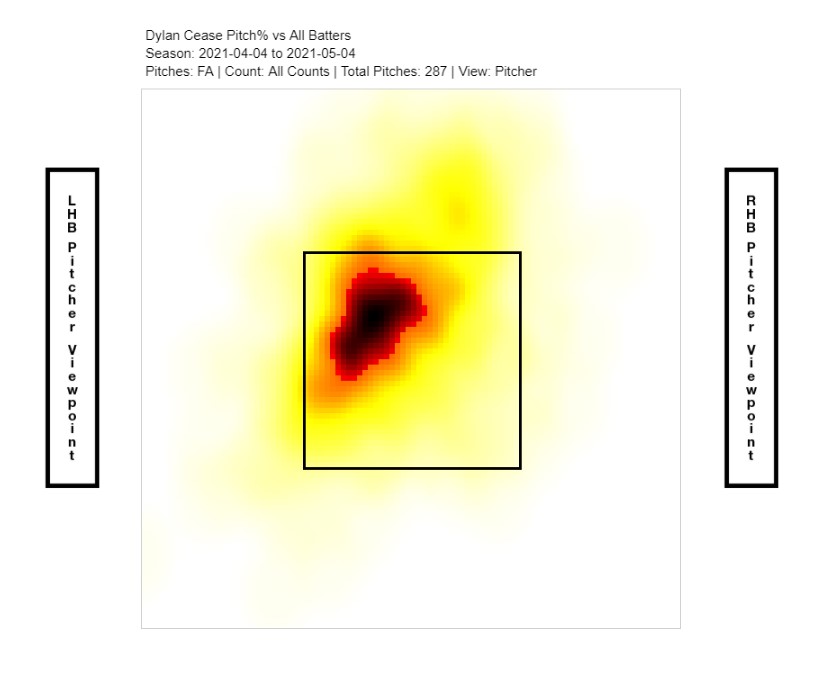

That’s a boatload of weak contact that just wasn’t there in the past. But it’s not happening in a vacuum. These changes are all occurring in concert with each other on a hitter-by-hitter level. The walk numbers still aren’t pretty and probably won’t ever be, but it seems that there is evidence that his offseason mechanical work is leading to some stabilization. Related to mechanics, location is another part of the equation that Cease has changed up a bit, in that he seems to be doing a better job of varying his fastball locations around the top of the zone, without actually throwing it in the zone any less:

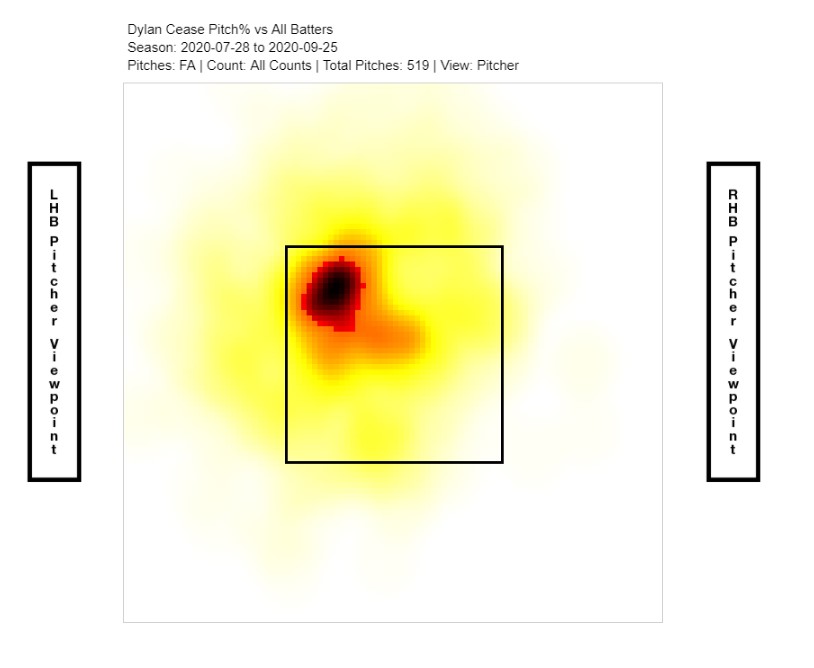

It’s a subtle change, but combined with improved movement, this seems to track with the batted-ball numbers suggesting hitters just aren’t as comfortable swinging against the fastball as they were last year. Look at the first heat map from last season, and put yourself in the hitter’s shoes. When Cease is struggling with control and nowhere near the zone with half of his pitches, as he does for hitters and whole innings at a time, it’s really easy for a batter to just sit on a fastball — especially one without a whole lot of rise on it — that you know is going to the same spot. Looking at a zone plot of all the extra base hits he gave up last season, we don’t see hitters putting good swings on pitches that are well-executed. We see two different kinds of pitches: sliders and changeups hanging in the middle of the zone, and middle-high fastballs that will always get crushed if a hitter is looking for it:

All that being the case, going back to Cease’s first start of the season, something tells me that Shohei Ohtani knew exactly when he was looking for when he swung at the first pitch he saw and took it 450 feet at 115 mph:

That pitch aside, however, hitters haven’t been able to sit on the letter-high fastball in the same way they were last year. Going back to the chart with his numbers on fastballs over the heart of the plate, just look at how many pitches that were balls in play last year are either whiffs or foul balls this year. And of the balls that are being put in play this year, look at how many of them are popups. Overall, the popup rate on Cease’s four-seamer is nearly 42%, easily the highest among all pitchers with at least 30 batted balls. Not everything can be attributed to getting more rise on the fastball, but this probably can — even when hitters are geared up to swing at the fastball, they’re just getting under it a lot more than they were in the past. Ohtani may have been able to convert on the high heater he was looking for, but hitters have far more often looked like this against Cease’s four-seamer, even in advantage counts:

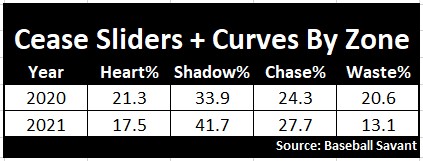

Once again, none of these things are happening independently of each other. This goes hand in hand with improved control of his other pitches. Every part of a pitcher’s arsenal works symbiotically with the other; a large part of a fastball’s ability to make hitters uncomfortable depends on how big or small of a threat posed by the possibility of seeing a different pitch. When things aren’t going well for Cease, part of the problem is often that he can’t throw his breaking balls consistently enough to keep hitters off the fastball. In 2019 and 2020, far too many of his sliders and curveballs wound up in the waste zone, and not in the way that Shane Bieber’s knuckle-curve ends up in the waste zone. When I say he has trouble consistently throwing his breaking balls, I mean he’s had trouble even executing them to the point that the hitter can’t relax as soon as it leaves the hand:

Pitches like those are still happening more often than one would like, but overall, Cease has done a much better job in 2021 of keeping his breaking balls close to the plate, which explains a healthy amount of their uptick in production. Unless you’re someone like Bieber, who has 70-grade command and an arsenal perfectly tailored for his particular curveball in the dirt, it’s nearly impossible to be successful when you’re throwing as many wasted pitches as Cease was in 2020:

Now it’s easier to see how all of this is working together. Here’s one way we can frame the 4% dip in pitches over the heart and 8% dip in pitches in the waste zone we see in that chart: if we assume that Cease is expected to throw roughly 90 pitches per start (he’s averaged a touch over 93 pitches/start for his career), and we expect roughly half of his pitches to be offspeed and breaking balls, we’re now talking about an extra 4-6 pitches per game that were previously either down the middle or automatic balls, and making them at the very least competitive pitches.

It’s not unimportant that almost all of those more competitive breaking balls are being channeled into the shadow zone, either. League-wide this year, curveballs and sliders in the shadow zone have resulted in a 45.9% CSW and .124 wOBA. Breaking balls in the chase zone, meanwhile, have a CSW of 18% and a .288 wOBA. It’s not an exaggeration to say that even though it hasn’t shown up in his walk totals yet, Cease has essentially taken a huge chunk of his least valuable pitches and turned them into the most valuable kind of breaking ball a pitcher can throw, at least location-wise.

Slightly improved control seems to have allowed Cease to both vary his fastball locations more than he’s done in the past, and also throw fewer wasted breaking balls than he’s ever done before. The result is that even though the fastball isn’t an elite pitch on its own, hitters simply haven’t been able to punish it in the same way they did before. Combined with a 50% usage rate, it’s accumulated a lot more value than other metrics think it should have. wOBA doesn’t account for foul balls and other pitches that don’t end an at-bat, and given that his control is still poor, much less his command, Cease is probably always going to run lower CSW numbers than his stuff dictates he should.

Putting It All Together

It’s likely that he’ll always walk a very fine line when it comes to executing enough competitive pitches to be successful. With each passing start, it gets more and more unlikely that Cease has the same kind of eureka moment with his control that Michael Kopech seemed to have had mid-2018, when he walked 56 hitters in his first 82.1 Triple-A innings before flipping the switch for a 51/4 K-BB rate over his final 44 IP in the minor leagues.

That being the case, Cease’s success will hinge on his ability to just be near the zone consistently, and limit the number of pitches that a hitter can either give up on instantly or sit on and crank 400 feet. He doesn’t need to have much command to do that, he doesn’t even need to have exceptional control. He’s finally optimized his fastball, and his secondary pitches are filthy enough that as long as he’s not flat-out giving away at-bats with grooved heaters and sailed curveballs, hitters are going to be really uncomfortable in the box. Unless that switch magically flips, he’ll still have games where his mechanics and proprioception just aren’t there, in which case he’ll still put up five-walk stinkers now and then. He can also have efforts like his seven-inning complete game against Detroit; when he does have some semblance of command, he’s close to unhittable.

As is almost always the case, the reality on a game-by-game basis is somewhere in the middle. The Detroit CG is quite nice, but still probably more the exception than expectation going forward. His follow-up in Cincinnati, however, with three walks but no earned runs and nine punchouts in six innings, might be the kind of high-end but high-wire act that we can look forward to in the near future. There’s not necessarily much reason to believe he’ll be that much more consistent than in the past, but there’s certainly evidence that his baseline is going to be a lot higher going forward than it was for most of his first two partial seasons at the big league level. Who knows whether he’ll make good on it or not, but I’ll be watching his next few starts a lot more closely than I was before. There aren’t too many pitchers capable of putting up a sub-three ERA while walking more than four hitters per nine innings, and it’s only been done three times by a qualified starter in the Wild Card era. Cease is probably one of those pitchers, and right now, he’s on pace to join Al Leiter, Daisuke Matsuzaka, and Clayton Kershaw as the fourth to do so. It would be yet another weird feather in the cap of what promises to be one of the most statistically weird seasons we’ve ever seen.

Photo by John Cordes/Icon Sportswire | Feature Image by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)

His stat cast is pretty red though