In April of last year, five Republican senators introduced a bill intended to strip MLB of its antitrust exemption. The legislation was a tit-for-tat response to the MLB’s decision weeks earlier to move the All-Star Game from Atlanta to Denver to protest a controversial election reform law enacted by the Georgia legislature.

The senators’ efforts never gained much support and fizzled behind other congressional priorities. However, in December, another threat to MLB’s antitrust exemption appeared in the form of a lawsuit brought by minor league teams whose affiliate status was revoked as part of MLB’s restructuring of its minor league system. That suit is ongoing and will likely work its way through the court system in a series of decisions and appeals in 2022 and beyond.

Unless you happen to be a legal historian, it’s difficult to understand how the MLB benefits from its antitrust exemption, or why the exemption is being attacked. Although the MLB is the only American sports league that is protected from antitrust lawsuits, its operations don’t appear significantly different from the NBA, NHL, NFL, or any other league on the surface.

The short answer to why the 100-year-old legal peculiarity known as the antitrust exemption still matters: it’s the get-out-of-jail-free card that enables MLB to pay minor leaguers pitifully low wages. The long answer to that question takes you through all the twists and turns of MLB’s labor history and reveals every other benefit MLB enjoys from its unique legal status on the way. It starts in the middle of the First World War.

The Origin of the Antitrust Exemption

In December 1915, the situation was dire for the Baltimore Terrapins. The publicly owned team was $65,000 in debt (roughly $1.76 million in 2021 dollars) and had been abandoned by the other members of the recently dissolved Federal League.

The Federal League was a venture started by some of the era’s business heavyweights, such as oil tycoon Harry Sinclair and league president James Gilmore, a manufacturing executive. For a two-year stint, the Federal League directly challenged the older, more established National and American Leagues for fans and players. It did so by drawing talent away from its two older siblings with significantly higher wages.

The American and National Leagues retaliated by implementing lifelong bans against any player that signed a Federal League contract. Some players took advantage of the Federal League teams’ willingness to spend cash, but most used it as a bargaining chip to pry better contracts from their current employers. Meaningful defections were limited to older stars who didn’t have much baseball left to play.

By 1915, as a result of economic turmoil caused by the First World War and skyrocketing payrolls, the Federal League’s business model proved unsustainable. The owners tried to salvage their investments by cutting deals with the major leagues. Of the eight teams that comprised the Federal League, several owners accepted buyouts; others were allowed to purchase franchises in the American or National League, and three were left without a deal or a league to play in. The citizens of Baltimore and their Terrapins fell into this last category.

Left with few options, the Terrapins’ shareholders convened an emergency meeting and voted to sue the major leagues and a host of baseball owners and executives. They claimed the defendants conspired to destroy the Terrapins by monopolizing the business of baseball. The basis of the suit was the Sherman Antitrust Act, legislation passed in 1890 designed to safeguard the function of the free market by outlawing monopolistic practices.

The Terrapins’ case ultimately wound up in the Supreme Court as Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc., v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs et al. (commonly referred to now as Federal Baseball), which was heard in 1922. The decision in the case, which went against the Terrapins, is the origin of the current MLB’s antitrust exemption.

The court’s majority opinion, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, was that baseball is not subject to the Sherman Act because “the business is giving exhibitions of baseball, which are purely state affairs.” Under this interpretation, baseball games are considered local events governed solely by state law. This meant baseball was not interstate commerce and thus not subject to the Sherman Act’s antitrust provisions, which are grounded in the Federal Government’s constitutional authority to regulate interstate commerce.

That decision protected organized baseball from a wide range of legal trials through the rest of the 20th century and continues to do so now, almost 100 years later. But not every decision has gone in MLB’s favor. The power the league gained from its exemption was chipped away over time. The most significant blow came in the wake of a pyrrhic victory for the league in a battle over the reserve clause.

The reserve clause was a section of every MLB player’s contract that stated the player was not free to enter into a contract with another team without being explicitly released by his current employer. Unless specifically provided otherwise, contracts were renewed on an annual basis. Players under contract could be reassigned, traded, sold, or released as the team saw fit, leaving them with little power to negotiate higher wages.

Each season, players were forced to choose between re-signing with their current team and abiding by its decisions or sitting out a full year and forfeiting a year’s wages before seeking employment somewhere else.

The clause had roots in the early formation of professional baseball leagues in the 1870s, when teams realized competition for players would cause a steep rise in salaries. They initially nipped that problem in the bud through informal agreements to not recruit each others’ players. These agreements eventually developed into a contractual system through which teams would effectively own players for the course of their careers.

In 1969, three-time MLB All-Star Curt Flood was traded to the Phillies against his wishes. Rather than go quietly, Flood brought suit against the MLB and chose to sit out the 1970 season, forfeiting $100,000 in earnings in the process.

Cardinals All-Star Curt Flood led the fight against the reserve clause

The case was a direct challenge to the reserve clause, and Flood sought $1 million in damages along with the removal of the clause from baseball’s contracts.

The case worked its way through the lower courts and was heard by the Supreme Court as Flood v. Kuhn in 1972. The named defendant was Bowie Kuhn, the Commissioner of MLB at the time. The ruling in the case was a disappointment for Flood and opponents of the reserve clause: the justices ruled 7-2 in MLB’s favor.

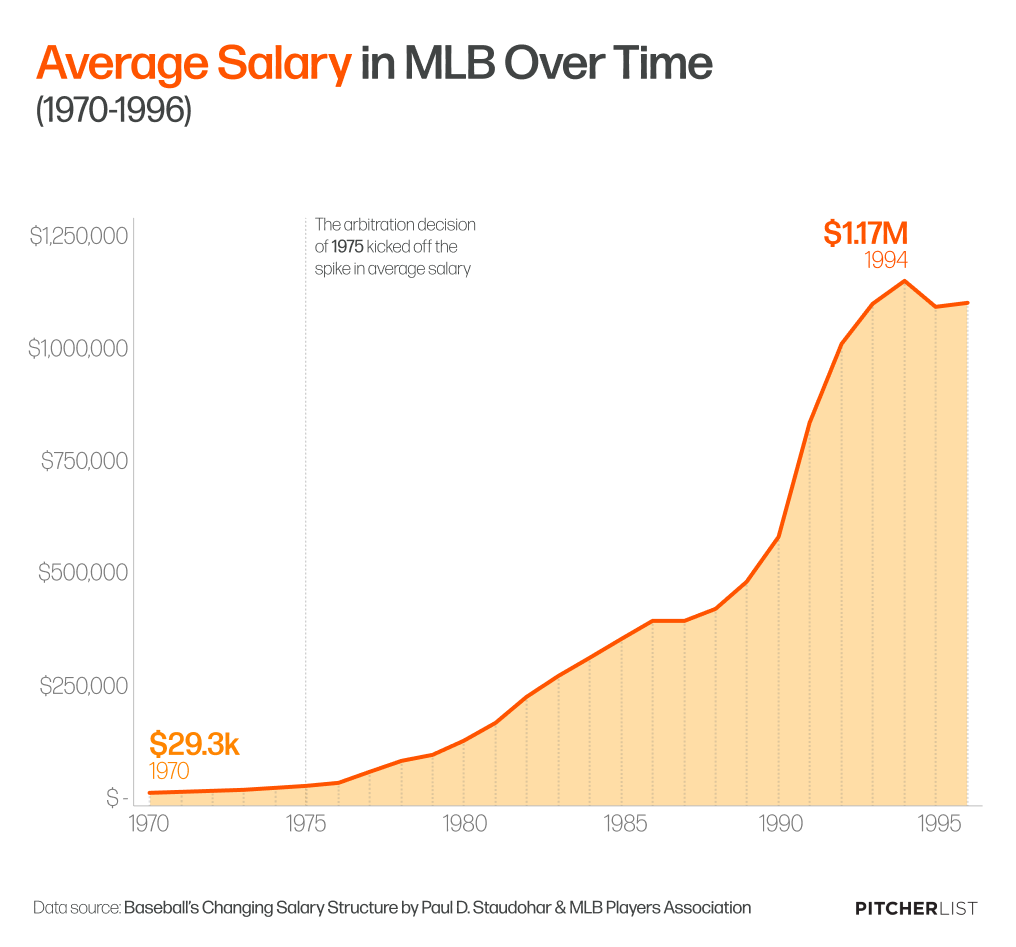

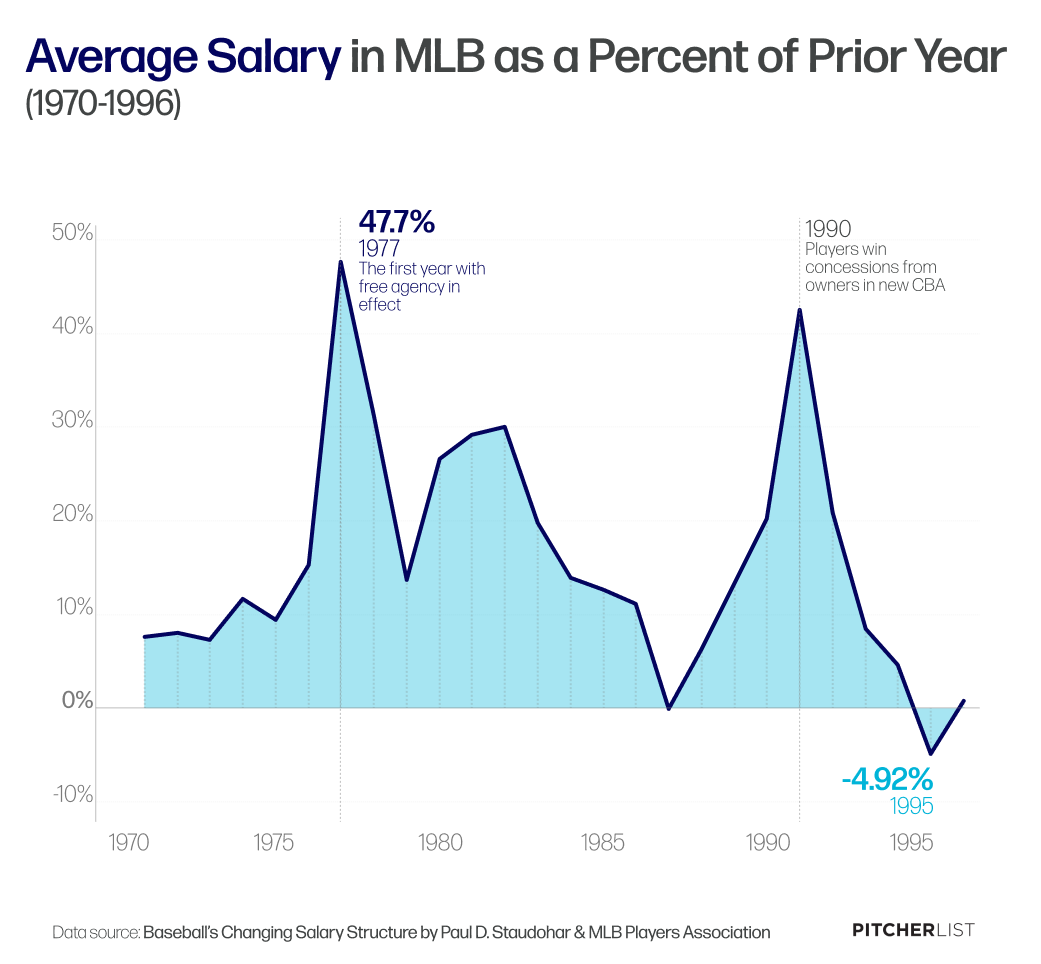

Despite Flood’s loss, the case made crucial inroads in the campaign to eliminate the reserve clause. It helped motivate players to organize against MLB’s labor practices and also focused national attention on the detrimental effects of the clause. Modern free agency, in which contracts do not automatically renew and players are able to entertain competing bids from teams after their contracts expire, followed 1975’s Seitz decision that concluded a subsequent labor arbitration. After that change in 1975, players won back a lot of power in negotiating contracts, and salaries climbed as a result.

While players are no longer subject to the reserve clause and the perpetual team control that came with it, the antitrust exemption remains. This leads us back to the question: if MLB can no longer rely on the exemption to control MLB players’ wages, why does it still matter?

To answer that question, let’s take a look at three other lawsuits against the MLB, and imagine how they might have turned out if Flood had won his case and the legal precedent established by Federal Baseball had been fully overturned in 1972.

Wrigley’s Right Field Rooftops

The Background: Since the late 1930s, fans can view games from outside the grounds of Wrigley Field in Chicago by purchasing seats on the top of buildings surrounding the stadium. The Cubs sued the owners of the properties in 2002, alleging copyright infringement for the sale of tickets to view the team’s “product”, and won a settlement that earned the team 17% of the gross revenue from sales of seats on the rooftops. As part of the settlement, the Cubs agreed to not erect barricades that would block the view of games from the rooftops, with the exception of an expansion that was “approved by a governmental authority”.

The Case – Right Field Rooftops, LLC v Chi. Baseball Holdings, LLC: In 2015, the Cubs received a government-issued permit to update Wrigley Field with electronic signs and billboards that would block the view from the rooftops. Some of the owners of the rooftop facilities, Right Field Rooftops, LLC., sued the Cubs, claiming the team engaged in anti-competitive practices to put them out of business.

What might have happened without the antitrust exemption: With no explicit legal protection exempting the MLB, and by extension the Cubs franchise, from lawsuits against monopolistic business practices, Right Field Rooftops could have successfully argued that the Cubs could not erect structures that would inhibit the view from their facilities. Wrigley would have gone without electronic scoreboards, and the view from the buildings overlooking right field would remain.

What actually happened: The Cubs argued they were exempt from antitrust claims and the federal district court ruled in their favor, pointing to Supreme Court precedent.

What this case tells us more broadly: This case demonstrates how MLB franchises can be much more aggressive in their dealings with related businesses thanks to the antitrust exemption. However, it’s worth noting the decision in this case also stated that even without Federal Baseball and other Supreme Court precedent, the lawsuit’s chance of success on antitrust grounds was slim.

Even if the antitrust exemption had not come into play, the clause in the agreement between the Cubs and Right Field Rooftops that allowed for expansions to Wrigley with government approval might have been enough for the Cubs to win the case. Additionally, the court observed Right Field Rooftops had no plausible market for its seats apart from Cubs fans, further weakening the business’s case.

That said, the presence of the antitrust exemption may discourage businesses from filing lawsuits in the first place, as the plaintiffs would see results like Right Field Rooftops, LLC v. Chicago Baseball Holdings, LLC. and know MLB franchises hold a silver bullet when it comes to anti-competitive practices.

The San Jose A’s

The Background: The Oakland Athletics have been seeking a new stadium since 2001. The franchise’s ownership pursued a myriad of options for new sites in the past 20 years. One of the most promising opportunities came in discussions with the city of San Jose, which is located roughly 43 miles south of Oakland.

The Case – San Jose v Commissioner of Baseball: While in discussions with the A’s to move the team to San Jose, the city of San Jose sued the MLB in 2013. Because San Jose falls within the San Francisco Giants’ territory, the A’s needed 23 of the 30 MLB owners to vote in their favor to approve the move. Anticipating that the team would not get the needed owner support, San Jose sought to force the move by arguing that the MLB was illegally restricting its franchises’ movement.

What might have happened without the antitrust exemption: Without any legal precedent exempting MLB from antitrust practices, San Jose might have won its lawsuit in the district courts with the understanding that the A’s had as much right as any other pro sports or business franchise to move as they saw fit. The MLB’s owners would have been sidelined while San Jose completed talks with the A’s, built a stadium in the city’s Diridon district, and helped the team move in.

What actually happened: The district courts ruled against San Jose, citing the antitrust exemption as the legal basis for MLB’s power to restrict its franchises’ movement. The case was appealed up to the Supreme Court which refused to hear it, ending San Jose’s bid. The A’s continue to pursue a new ballpark.

What this case tells us more broadly: The “San Jose A’s” saga is a tangible example of how the antitrust exemption empowers the league to dictate aspects of how its franchises do business. The extent to which the league benefits from that power is debatable, but there’s no question the franchises would get a boost of autonomy if the exemption is removed.

Minor League Pay

Background: In 1998, Congress passed the Curt Flood Act and curtailed MLB’s antitrust exemption as it related to labor relations with major league players. However, the act did not extend protections down to the minor league level, and teams continue to artificially suppress minor league wages.

The Case – Miranda v Selig: In 2015, four minor league players sued MLB, alleging the league’s employment policies violated antitrust laws by limiting competition between franchises and suppressing minor league salaries.

What might have happened without the antitrust exemption: Without the legal precedent from Federal Baseball, MLB would have no legal defense for suppressing minor league salaries below federal minimum wage. Minor league players could win concessions in the form of housing paid for by the league, higher per-diem pay for food on the road, and starting salaries comparable to those paid to their counterparts in the NHL and NBA’s development leagues.

What actually happened: A district court ruled in favor of the MLB, and on appeal, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. The summary of the case stated:

“The panel concluded that because it was bound by Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit precedent upholding the business of baseball’s exemption from federal antitrust laws, and because Congress explicitly exempted minor league baseball in the Curt Flood Act of 1998, the players failed to state an antitrust claim.”

What this case tells us more broadly: Removal of the antitrust exemption will be most impactful on MLB’s relationship with the minor leagues and their players. Minor leaguers are fighting the same battle Curt Flood lost in 1972. They will continue to do so until MLB’s legal status is changed through new legislation or additional cases reaching the Supreme Court.

Of the three examples of MLB’s benefits from its unique legal status, the last one clearly stands out. The league gaining legal protection from esoteric lawsuits protecting its franchises from rooftop snoopers or limiting its teams’ movements isn’t a societal issue. MLB suppressing salaries to the degree that it’s causing a mental health crisis among players is.

If the MLBPA is serious about its intentions to help young players, it might do more good lobbying against the antitrust exemption empowering wage manipulation than it will holding out for higher minimum wages during the lockout. After all, only a fraction of minor leaguers will ever get the opportunity to benefit from the higher minimum.

The good news is public awareness of the plight of minor league players is rising, and MLB is finally making changes to improve conditions for prospects. With a sustained, unified effort from fans, politicians, and players, conditions for minor leaguers will continue to improve, and the antitrust exemption can finally be left behind as a legal vestige of a bygone era.

Featured image photo by Archives de la Ville de Montréal/Flickr | Adapted by Michael Packard (@artbyMikeP on Twitter & IG)

Facts and story related to the Baltimore Terrapins and the origin of MLB’s antitrust exemption adapted from a speech by Justice Samuel Alito, published by SABR

Portrait of Curt Flood accessed from Wikimedia Commons

Salary data visualizations created by Tina Covelli (visual_endgame on Twitter), using data from Baseball’s Changing Salary Structure by Paul D. Staudohar

A’s logo adapted by Michael Packard (@artbyMikeP on Twitter & IG)

Photo of Wrigley Field accessed from Wikimedia Commons

Suggested additional reading: Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption series by Fangraphs’ Nathaniel Grow

Great piece!

Thank you for reading!