I spent many a day with a newspaper in my hand, scanning box scores trying to an idea of what was happening in the world of baseball, who was a good player, and who was doing well. The absolute worse part was that the paper, except on Sunday, was delivered in the evening, prolonging my wait.

Except for the occasional shows on television or a blurb about something interesting on the local news, there was little day-to-day information available to a 12-year-old in the early 80s’.

Games had to be recreated by the wonderful box scores and weekly Sunday list of leaders. For that, we have to thank an Englishman that, in 1856, finally found a “base ball” contest that pulled his interest away from cricket. That man, the “Father of Baseball”, was Henry Chadwick.

Born on October 5, 1824, in Exeter, England, Henry Chadwick moved to Brooklyn, New York, in September 1837. He moved with his father and his father’s wife from his second marriage. Henry’s half-brother would stay and eventually be knighted for his work on sanitation problems.

Henry would soon, like his father, become a journalist, and, eventually, the cricket writer for the New York Times. Chadwick’s love for the game would help him cast a shadow on the game until he died in 1908. While William Cauldwell was the first journalist to report about baseball, Chadwick soon surpassed Cauldwell. When he moved to the New York Clipper, a weekly that was read nationwide, the game of baseball and the game would spread out to Boston, Philadelphia, and beyond.

In 1858, the National Association of Baseball Players was formed, naming Chadwick as the chairman of the rules committee where he would write the first rules book. His prominence with the rules led umpires, when he attended games, to stop the action to provide clarification on calls. They didn’t have video replay, but they did have Chadwick Reviews, apparently.

Chadwick the journalist needed a way to better describe games in pre-Civil War print. He didn’t have photography to enhance his stories nor video to show highlights. He couldn’t work play-by-play accounts of every play on every game in the limited inches available to him. Falling back on his knowledge of cricket, in 1859, he modified a cricket box score for baseball and developed a scoring system to record the events of the game. His scoring system was a 9×9 grid to record the events. Nine innings across, nine batters down. That system is much the same now. He tended to use the last letter of works and hence, the ‘K’ for Struck (out) was defined. From his scoring system, he created the box score. The box score changed many times over the years, but the central idea of the box score has remained the same since 1859, or a little over 150 years.

A Look Back to 1892

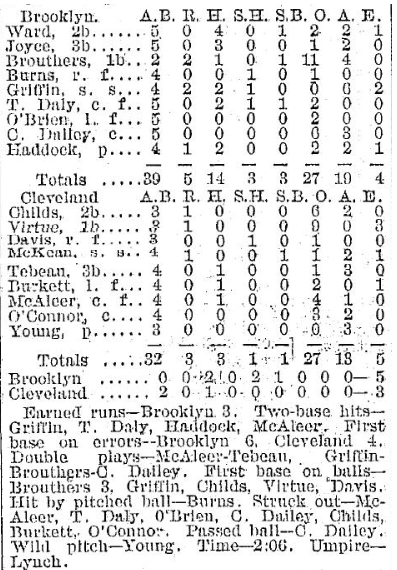

Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio) June 7, 1892, Page 4, Column 3, IN A DREARY RUT

By 1892, a typical box score might look like this one from a June 6, 1892, contest between Cleveland and Brooklyn (Young, p here is Cy Young. Yes, that Cy Young).

O is put Out, A is assists, and E is errors. Hitting stats include A.B, at-bats, H., hits, and S.H. Sacrifice hits (typically bunts).

What can we get from the box score?

Brooklyn’s first baseman had 11 outs, the catcher at 6 outs (mainly from strikeouts) and the rest of the infield had 10 assists. Brooklyn’s outfielders only had 5 outs and no assists. Brooklyn’s Haddock was more of a groundball-type pitcher, a good Cleveland offense in check, scattering just three hits.

Cleveland on the other hand had outs spread out across the field. Everybody had at least one out and everybody but the corner outfielders and the first baseman had an assist. I get the feeling that Cy Young was pounded pretty well, giving up 14 hits and seem to go all over the place. Despite FIVE errors, three for the first baseman, the game was pretty close.

Of the 8 runs in the game, only 3 were earned. All of Cleveland’s runs were unearned, while only two of Brooklyn’s were unearned.

Given just the box score you could get a good sense of the game, what happened. You can see a Brooklyn team cruising along while Cy Young battled with Cleveland sputtering at the plate.

Looking at box scores, what does that tell us about baseball in 1892? The standard pitching line we are used to seeing is missing. What the pitcher did is left almost as footnotes at the bottom of the box score. With the sacrifice hits and stolen bases included with the at-bats and runs, moving runners was an important part aspect of the games. Outs, Assists, and Errors? In the batting line? Fielding was a focal point in the game at the time.

There is a lack of accumulating stats. Batting averages are no were to be seen. We have no idea, in the box score, who had any runs batted in. The box scores, even then, were lacking. Where the cumulative ERA for the pitchers?

But, Chadwick’s scoring system gives us enough information, even now. We can calculate that Cleveland’s second baseman Cupid Childs topped the league with a 0.443 On-base percentage in 1892. Tabulating the box scores will give us the information to see that Jesse Burkett topped Cleveland with 6 home runs in 1892 and shortstop Ed McKean led the team with 93 RBIs. We can invent a stat like save and retroactively discover Goerge Cuppy and John Clarkson each recorded a save in 1892. Cy Young had a 2.76 FIP in his 453 innings pitched for the 53 games he appeared in, 49 which were starts. Twenty-five years old at the time, Young’s arm could take the load. Because of Henry Chadwick’s invention, we know that those 453 innings were the most in his career. We can see that in the first four years of his career, he pitched over 400 innings each year! We can go back in history and see an amazing career based on box scores.

Chadwick gave baseball fans and historians a way to understand the game and retroactively discover it. He did so with limited technology. Heck, Chadwick didn’t use a typewriter, handwriting everything. (I toyed writing this longhand and scanning it in, but my handwriting was label “disturbing” in fifth grade. It hasn’t improved since then).

Henry Chadwick influenced baseball for 52 years. He wrote volumes about baseball in The Sporting News, and Sporting Life. As an editor, he spent decades shaping the narrative of Beadle’s Dime Baseball Player, DeWitt’s Baseball Guide, Our Boys’ Baseball Guide, Haney’s Book of Reference, and the Spalding Official Baseball Guide. In the early 1880s, he wrote The Art of Batting and Base Running. He helped with the rules while integrating stats and writing instructional books and be forwarding thinking enough to give us data from the past that is useful in the future.

But this is only the beginning. Henry Chadwick used the data and how that data would be used to influence the game. This was his stepping stone. If you want to understand how data analytics is affecting the game today, you can’t do it unless you understand the impact of introducing data into the game. That is a second story that includes labor strifes, player strikes, owners crying poor, and cheating. Sound familiar?

Henry Chadwick as baseball’s first publicist and baseball’s first statistician bestowed box scores to us so I guess we can forgive him for also inviting the RBI.

Photos from Library of Congress | Design by Quincey Dong (@threerundong on Twitter)