Entering Memorial Day weekend, Major League Baseball players are hitting a collective .236. That mark is the lowest since 1968, a season that is commonly referred to as the “Year of the Pitcher.” Because the power numbers remain among the best the sport has seen, the league’s .705 OPS is actually middle-of-the-pack. However, strikeout numbers are at an all-time high, and no-hitters are being thrown (or at least flirted with) on a near-weekly basis.

Whether you are an old-school or new-school fan, most will agree that the current offensive climate is not what is best for the game. In order to find a solution, the cause of the problem needs to be identified first. Some former MLB players believe that they have this step covered. A recent example is Seth McClung, who pitched across parts of six seasons from 2003-2009. The former hurler shared his thoughts on the current state of the game in a video he posted to Twitter.

Me quickly explaining what’s going on in today’s mlb game #SheGone @O3jfrye @rtheriot7 @batflips_nerds pic.twitter.com/cWrbtcuKa3

— Seth McClung (@Seth_3773) May 20, 2021

Give McClung credit for laying out his opinions clearly and concisely. This was not some sort of angry and incoherent rant. I encourage you to watch the video in its entirety, but here are some of his main points:

- pitchers are not as good as some fans believe they are

- hitters are no longer eliminating pitches in certain situations

- hitters are instead swinging at everything in an effort to hit home runs

- pitchers do not have to throw strikes because they know hitters will chase

- pitchers are using “sticky stuff” (banned substances) to increase spin and movement

McClung acknowledges that pitchers are throwing harder and with more movement, and there is an extremely high chance that he is correct about the use of substances to make pitches harder to hit. However, he places much of the blame for the lack of hits on hitters themselves and criticizes them for having poor approaches at the plate. It is pretty well known by now that front offices value power. After all, a home run is the easiest way to score a run because it only requires one swing of the bat. Has the focus on home runs facilitated poorer overall approaches as some claim? Let’s work through Seth McClung’s argument and see if there is statistical evidence to support or dispute it.

Hitters Are Not Swinging at Junk More Often

For the most part, McClung is off with his first assertion. Let’s attack this specific argument from a few angles.

Overall, the rate at which hitters across the league swing has remained fairly consistent. FanGraphs began tracking plate discipline statistics in 2002. Since then, the league-wide swing rate has sat between 45% and 47% each year. There is no evidence that hitters have started swinging at more pitches overall.

Interestingly, there was a significant jump in swing rate on pitches outside of the strike zone once the 2010s began. In 2002, hitters swung at just 18.1% of pitches outside of the zone. In 2009, McClung’s last season in the league, that figure was up to 24.9%. By 2012, it ballooned to 30.2%, so there has been some degree of change since he hung up his spikes. However, the chase rate has stopped increasing since 2012 and remained around 30%. The figures for 2012 and 2021 are nearly identical, but there is a difference of nearly five percentage points in strikeout rate. Furthermore, this stat does not differentiate if hitters are swinging at pitches well outside of the zone or pitches just off the corner that they deem too close to take.

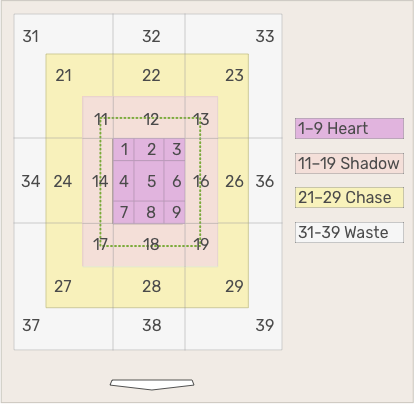

To find out if hitters are really swinging more often at bad pitches, we can turn to more detailed pitch location data available from Baseball Savant. This data goes back to 2008, so it includes the final two years of McClung’s big league career. The location filters included in Savant’s search tools are comprised of four zones, including the “chase” and “waste” zones pictured below.

Pitches in the “chase” and “waste” zones are pitches that a hitter should avoid swinging at. You’re not going to get hits by taking cuts at those. Have hitters started swinging at these offerings at a higher rate? The data says that they have not.

The swing rate on pitches in the “chase” zone has actually gone down slightly since McClung last played. The figure for waste pitches has crept up over 6% on a few occasions, but there is nothing here that suggests that hitters have started flailing at more terrible pitches. The 2021 swing rate on waste pitches is extremely close to the 2008 rate.

Maybe hitters are taking more cuts at pitches just off the plate, but are they, to use McClung’s own words, “swinging at absolutely everything” because they are overly eager to hit a home run? No. There is no strong evidence to support the notion that hitters have made it easier for pitchers by swinging at pitches they shouldn’t be.

Eliminating Pitches is More Difficult Than Before

McClung moves on to another flaw that he believes exists in the modern approach. He claims that hitters are no longer eliminating pitches. Instead, he declares that they are swinging freely at any pitch with no regard for the situation because they are so focused on going yard. He uses 2-1 and 3-1 counts as examples. A hitter may hunt a fastball and rule out swinging at a breaking ball. This is because he believes the pitcher is likely to throw a fastball to get back in the count.

There appears to be some substance to McClung’s observation that hitters are no longer eliminating pitches like they used to. While the amount of swings on 2-1 and 3-1 non-fastballs has not changed all too recently, it is notably higher now than it was in 2008 or even 2010.

What set the ball in motion for this change? Contrary to what the old-school crowd believes, it is not because hitters became undisciplined in their quest to hit more long balls. Instead, it is a response to a change made by pitchers. Not only are hitters seeing more breaking balls and offspeed stuff in hitter’s counts than they used to, but pitchers are locating them in or near the strike zone more often as well. Once again, we can refer to Savant’s zone chart pictured above.

Just as McClung’s big-league career was winding down, pitchers started to improve at locating secondary pitches in or just outside of the strike zone in hitter’s counts. At the same time, fastball usage in these situations began to steadily decline. That brings us to today, where it is harder to eliminate pitches and hunt a fastball. As a hitter in 2021, you will still see more fastballs than any other pitch when ahead in the count, but you are also far more likely to get a breaking ball or changeup than you used to be.

When someone points out that hitters are not eliminating pitches as they did in the past, there is some level of truth to that. However, it is not because they have become too aggressive. It is because pitchers have become more unpredictable. From a pitching perspective, we often talk about keeping a pitch in the back of a hitter’s mind to keep him off-balance. That is essentially what is happening on a league-wide scale.

Launch Angle is Not the Problem

McClung never specifically mentions launch angle in his video, but this is a common complaint from the old-school crowd. It is also yet another point of conversation related to the approach of the modern hitter. Some argue that batters have become too focused on hitting the ball at a high launch angle to hit more home runs and that doing so creates flawed swings.

To be clear, there is such a thing as too high of a launch angle. No one wants to hit weak infield pop-ups, and no hitter goes up to the plate and takes golf swings at the ball. If there is any evidence that efforts to hit baseballs at a higher launch angle are to blame for the lack of hits this season, it doesn’t show up in a basic investigation. While the average launch angle across baseball has increased since Statcast began tracking it in 2015, the last time it increased by at least half a degree was from 2017 to 2018. The 2021 launch angle is actually very slightly down from previous seasons. Strikeout rates have continued rising, but launch angle is not.

How about fly ball rate? Fly balls have a low batting average, so if hitters are hitting more of them, that could be a factor behind the decrease in hits. A quick peek reveals that this is not the case. Batted ball numbers, particularly fly ball rate, have remained remarkably consistent over the past 20 years.

Some hitters change their swing and their approach for the worse by trying to hit for power. Generally speaking, hitting the ball in the air produces better results than hitting it on the ground, but not every hitter finds success by increasing his launch angle or fly ball rate. There is no perfect “one size fits all” approach. Some players may struggle because they become too consumed by a desire to hit for power. However, there is little to no statistical evidence that a systemic issue in the hitting approach across the league led to where we are now.

If hitting approaches should not shoulder most of the blame, then what should? Let’s search elsewhere for noteworthy changes.

Pitchers Are Throwing Harder Fastballs and More Breaking Balls

This is an obvious one. Not only has the average velocity on four-seamers, two-seamers, and sinkers risen in recent years, but the frequency of fastballs thrown 95 miles-per-hour or faster has doubled since 2008.

Big league hitters are capable of barreling up upper-90s heat and sending it 500 feet, but the fact is that they are still tougher to hit than a low-90s fastball. In the pitch-tracking era, hitters have batted a collective .284 with a 15.4% whiff rate on fastballs 94 miles-per-hour or slower. Against fastballs 95 or above, they have batted just .245 with a 21.3% whiff rate. Harder fastballs are not impossible to hit, but they are significantly more difficult to get a bat on.

It’s not just the uptick in fastball velocity that is producing more empty swings and fewer hits. We discovered earlier that pitchers have become less predictable by throwing more breaking balls in fastball counts. In the same way, the overall usage of various curveballs and sliders has increased dramatically since 2008. No matter which era of baseball you’re looking at, these kinds of pitches have always been harder to make contact with because of their movement. In the pitch-tracking era, 32.4% of swings against breaking balls have come up empty. That is significantly higher than either of the whiff rates listed above against fastballs.

All of this is to say that when you throw pitches that are harder to make contact with more often, the result will be more swings and misses. Pitchers have gotten better at missing bats.

New Technology and a New Baseball

Pitchers have also improved thanks to the rise of technology. Trackman and Rapsodo systems give pitchers instant feedback on how hard they’re throwing, the spin rate and spin axis of their pitches, pitch movement, and release points. Edgertronic cameras allow pitchers to see their delivery and release in slow motion at thousands of frames per second. They can pick out how the ball is coming off their hand and identify the slightest difference in their release point. Pitchers now have the tools to make their pitches more effective than ever before and make them look nearly identical out of the hand through pitch tunneling. Optimized pitches are more difficult to hit.

Some have argued that this trend has been expedited by the implementation of new baseballs. MLB modified the design of the ball for 2021 in an effort to put a stop to rapidly rising home run totals. Pitchers have claimed that the ball is lighter and that the height of the seams is different. The result is that pitches are being thrown harder and with significantly more spin and movement, making them even more difficult to hit than they already were. Rob Arthur cited some eye-opening trends in a recent piece for Baseball Prospectus.

The effects of the baseball on movement add to long-term trends in pitch design and optimization that have increasingly neutered hitters at the plate. Since 2018, just three years ago, curveball lateral movement has increased 25 percent, slider lateral movement 20 percent. Those changes didn’t all come this year and some may derive from a shift in tracking systems (in 2020, the league moved to Hawkeye camera tracking), but they’ve been accompanied by ever-increasing strikeout rates.

There is plenty of evidence from both the eye test and the numbers that pitchers are nastier than ever before. The evolution of pitching appears more to blame for the lack of offense than changes in hitting.

The Shift

But wait, there’s more! We cannot forget about the rise of shifting. As the analytics movement continues to grow within the sport, the presence of modified defensive positioning has skyrocketed. The batting average on balls in play (BABIP) began to decrease in 2018, and this continued as the usage of shifts exploded.

There has been some discussion of banning the shift to boost hit totals, but ideally, hitters will be able to adjust to it. That could mean shooting the ball to the opposite field, but that is easier said than done against rising upper-90s fastballs and secondary pitches that are breaking even more than they used to. An alternative is to hit more line drives and fly balls over the shift.

Pitchers Are Bad at Hitting

MLB.com analyst Mike Petriello recently offered a new explanation for the uptick in strikeouts. Pitchers did not bat at all in 2020 because there was a universal DH. National League hurlers are once again stepping up to the plate this year, and they have been even worse than usual, slashing a collective .104/.140/.135. Petriello noted that the strikeout rate for position players is actually the same as it was in 2020. Their batting average is still down by five points, but pitchers alone have dropped that figure from .239 to .236. It should be noted that this only serves as an explanation for the strikeout increase from 2020 to 2021, not the wider trend that has been going on for years.

Where Did the Hits Go?

Generally speaking, today’s hitters and evaluators are more focused on hitting for power than those of the past. Perhaps this makes some level of contribution to the high strikeout and low hit totals we are seeing right now, but there is not much data indicating that the hitters themselves are the main culprit. Rather, several elements are working together to create an increasingly unfavorable environment for getting hits. Pitchers are throwing more breaking balls, both overall and in hitter’s counts. They’re also throwing harder. New technology, a modified baseball, and possibly widespread foreign substance use have enabled them to generate even more spin and movement on their pitches. On top of it all, when someone does put a ball in play, teams have gotten so good at collecting and interpreting data to position their defenders in exactly the right locations to turn would-be base knocks into outs.

Maybe some fans and analysts have the cause-and-effect of baseball’s current conundrum backwards. What if an obsession with hitting home runs is not making the job of a pitcher easier? Instead, pitchers got better to the point where hitting singles and doubles is more difficult than it used to be. As a result, scoring runs by stringing hits together is not the viable strategy that it used to be. In today’s environment, perhaps trying to score with one swing of the bat as opposed to two or three makes more sense, especially since hitters have shown that they can continue to lay off bad pitches while doing so.

Ideally, hitters will adjust to the improvements in pitching and positioning. Maybe the offensive side of the game will experience an information and technology boom that puts hitters on the same level as pitchers. If not, Major League Baseball may be forced to take action. The lack of hits and an increasing number of strikeouts is a negative development for the sport, and there is nothing wrong with acknowledging that. Just think twice before placing the brunt of the blame on the athletes swinging the bats. To find solutions, we must understand what is causing the problem.

Photo by All-Pro Reels (https://www.flickr.com/photos/joeglo/) | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@JustParaDesigns on Twitter)

Case in point to refute the twitter rant: DJ LeMahieu. Granted, his first couple years in the Bronx supplied more than anyone was expecting, but the AVG has always been there, and it’s not now. If it were in a vacuum, you could say it was a slump or a guy having a bad year, but when the two-time batting champ is having this much of a problem laying down hits while AVG is suppressed across the league, it’s pretty clear something is off.

One other note: There seems to be a decent majority w/ influence within the MLBPA that are/were pitchers, beyond the lawyers and businesspeople.

I could be wrong about this, I haven’t dug in too deeply on this research, but many (a suspect a strong majority) of team reps, as well as the higher-ups within the PA itself that are listed on their website, are pitchers, and have been for a while. Maybe, rather than rule-changes, etc., MLB could ask for different representation among the players? I’d love to see more DH’s, etc., in there…

Just to be clear, I’m not advocating for MLB itself here, I kind of dislike Manfred and his goons, I’m just thinking that a more diverse coalition of positions should be represented within the MLBPA… And Tony Clark lasting this long is an absolute travesty. He needs to go before the CBA negotiations.