Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. Bright copper kettles and warm woolen … wait, sorry. Wrong list of my favorite things.

When you write enough about baseball, you find yourself starting to fall in love with certain things that stand out among the myriad of at-bats and plays in the field that make the game a unique experience for every fan who loves this beautiful game. Bat flips, an outfielder throwing out a runner at third, a walk-off hit to win a big game- these are genuinely a few of my favorite things about baseball. The past year, though, one thing has taken the top spot in my hardball life, and that’s the simple beauty of an elite changeup. Dependent on the right combination of movement, deception, and strategy, it feels like the thinking man’s pitch. When paired correctly with a fastball, it’s the pitching equivalent of the Rope-A-Dope Ali used to take down Foreman. I have never seen hitters look foolish quite like they do when flailing at a good changeup.

The other day, I was looking through a list of the best changeups by pVAL and saw most of the usual suspects, like Luis Castillo, Jacob DeGrom and Hyun-Jin Ryu. One name in particular, though, stuck out to me, and that was John Means. Last year (his rookie season), Means’ changeup was worth 14.1 pVAL, which was the 9th-best changeup of any pitcher in the majors who threw more than 100 IP. Naturally, I thought I had to check it out. Let me tell you; it’s a doozy.

Watch the end of that pitch again. At first, it moves like we expect a changeup to move: Down and away to the glove-side, but at the last second, it curves back arm side. I didn’t even know physics could do that. It’s practically a screwball. Now that I was sufficiently hot and bothered, I had to fully dive into John Means and his 2019 rookie campaign.

By all accounts, Means had a great debut season for the Orioles.

| IP | W | ERA | WHIP | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 155 | 12 | 3.60 | 1.14 | 121 |

There’s a lot to like there. The hard part is that it’s coming with a 19.0% K rate, a 6.0% BB rate, and a 5.02 SIERA. Looking at that, most people would say his success just isn’t sustainable. I don’t disagree at all with being skeptical whether Means can repeat those numbers in 2020. I’m honestly not here to sell you the idea that Means will be a sleeper stud in 2020. When our esteemed Papa Nick Pollack did his player profile on the Orioles’ starter, he labeled Means a Toby, and as it sits right now, he’s correct. Thing is, Means was a 26-year-old rookie. We’d be hard-pressed to assume he’s anywhere near a final product as a pitcher. It’s not like the template isn’t there either. So far, Means has flashed a four-pitch repertoire consisting of a mediocre fastball, an above-average slider, a godawful curveball and the aforementioned fantastic changeup that got us all started on this journey. The question that remains for Means is if we all accept as given that he isn’t going to develop a 96 mph fastball this offseason, or suddenly have Max Scherzer’s slider. Is there a blueprint already out there for him to follow that would allow him to take the skill he already has and still break out as a pitcher? The answer is yes, my friends, I do believe that there is. Come. Walk with me.

I want to compare Means to two different pitchers. One is a near-perfect match for his skill set, and the other shows the ultimate path to his eventual career ceiling. The key is that both of these pitchers have two of the best changeups in the game and poor-to-mediocre fastballs. As is required by the unofficial fantasy writer bylaws, I am contractually obligated to reveal my blueprint pitchers in the form of a mystery game!

| Player | K% | BB% | SIERA | O-Swing% | GB% | SwStr% | HR/9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Means | 19.00% | 6.00% | 5.02 | 32.30% | 30.90% | 9.90% | 1.34 |

| Mystery Player A | 20.60% | 4.40% | 4.38 | 35.10% | 41.30% | 10.30% | 0.97 |

| Mystery Player B | 23.10% | 3.70% | 3.96 | 35.20% | 45.20% | 10.50% | 0.91 |

In a general sense, we are seeing three different pitchers with below-average K%, similar overall profiles, and pretty high SIERAs. Mystery Player A is changeup-wielding extraordinaire Kyle Hendricks. Mystery Player B? Well, that is none other than ace pitcher Zack Greinke. All three pitchers have very similar arsenals (Hendricks doesn’t throw a slider, but as a changeup-first pitcher with a poor fastball, he feels like the perfect model for Means.) 2019 Greinke represents just how high his ceiling can get if every single variable fell perfectly into place over his career. By putting these players side-by-side, we can perhaps determine what improvements we need to be looking out for early on in the season and throughout spring training to see if we should be jumping on the Means bandwagon in 2020 and beyond. To do this, I want to go through each pitch these guys throw and see how they are similar and what changes need to happen for Means to fulfill his destiny.

Changeup

There’s no sense in starting anywhere but with the golden goose: The changeup.

| Player | Velo | Horizontal movement | Vertical Movement | Active Spin % | Spin Rate | Usage% | pVAL | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 80.9 | 24.6 | 12.3 | 92.00% | 2331 | 29.00% | 14.3 | 0.270 |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 78.6 | 34 | 13.1 | 74.50% | 2115 | 28.00% | -0.1 | 0.288 |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 87.4 | 32.4 | 12.5 | 68.60% | 1780 | 20.80% | 16.9 | 0.23 |

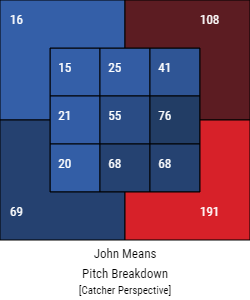

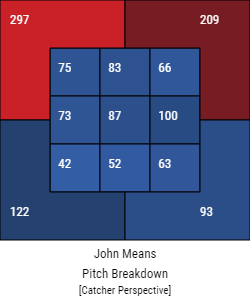

While they aren’t a perfect match in terms of movement, I have a feeling the horizontal movement is skewed a bit by how Means’ off-speed pitch curves back arm-side at the very end. The key though is that all of them are a changeup with significant horizontal and vertical movement in its flight path. For the record, I also suspect that the high active spin and elevated spin rate are responsible for that late arm-side break. In the long run, a higher spin rate is a good sign for Means’ changeup, as it indicates it should remain hard to hit. Greinke also throws his much faster, and considering his fastball comes in at about 89 mph or so, you have to wonder if that is part of its success. Since they mostly throw it roughly around the same amount of the time, I want to take a look at when and where they each throw their off-speed pitch. Here’s Means’ zone profile for his changeup.

Means threw 776 changeups last year, with 33.5% of them landing down and out of the zone. This is good, exactly what we want him to do, especially when you consider that he got a 38.9% O-Swing with a 68.2% O-Contact with his changeup. Hitters had a .170 xBA with a 0.057 ISO when they made contact with his off-speed pitches out of the zone. These are all great numbers. To add to that, 20.1% of his changeups were located at the bottom of the zone, and 9.8% were in the zone on the hands to right-handed hitters, and 2.7% in on the hands to lefties. These numbers are important because when you can also throw changeups in these spots, it can help blur the line between when the pitch is going to land for a strike or a ball. That’s huge for a changeup’s effectiveness, especially as a strikeout pitch and getting chases out of the zone. That’s 66.1% of his pitches going exactly where we want him to throw his changeup. How did the others fare?

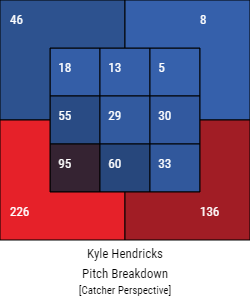

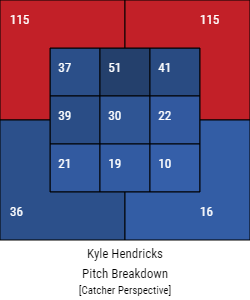

So, Hendricks threw his changeup down and out of the zone 48.1% of the time, with a 46.9% O-Swing and 63.5% O-Contact. When batters made contact with said pitches, they managed a .193 xBA and a 0.049 ISO. Again, that’s pretty darn good. In addition, he threw 25% of his changeups in the bottom of the zone, 11.9% in on the hands of righties, and 7.3% inside to southpaws. We’re talking about 92.3% of his changeups in the best spots to throw them. That’s really, really good. What about Greinke?

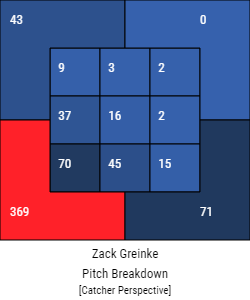

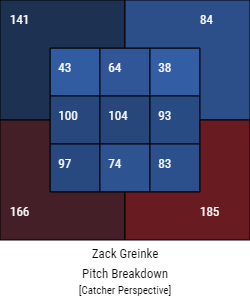

Greinke threw 67.9% of his off-speed pitches down and out of the zone. This is combined with a 45% O-Swing and a 60.8% O-Contact, which held hitters to a 0.022 ISO and an unreal .102 xBA. 20% of them were at the bottom of the zone, with less than 1.0% coming inside against righties and 5.7% inside to righties. That’s 94.6% of his changeups in the ideal spots. That’s near-perfect placement.

This points to the first big change Means need to make for his changeup. It’s already a great pitch, but he could take it to the next level if he starts locating it even more often down in the zone and outside the zone. He’s already getting hitters to chase it at a pretty great rate, but once he starts to blur the line between what is a strike and what’s not, the pitch could take an even bigger leap. You can see how Hendricks and Greinke got better results with their changeup. It can’t be a coincidence that they better located their changeups than him.

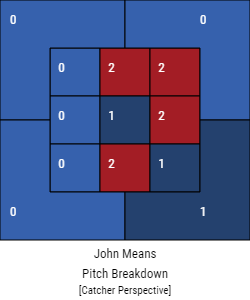

Last note on the changeup: Means allowed 11 homers on his changeup, compared to seven by Hendricks and three by Greinke.

Check out their location. All but three of them were located in either the middle or up in the zone. Again, this can’t be a coincidence. Let’s say we take away the five home runs that happened up in the zone or the heart of the plate. That would bring his HR/9 down to a much more respectable 1.05. That’s much closer to Hendricks’ and Greinke’s numbers from 2019.

Fastball

Now that we’ve looked at the elite stuff, let’s talk about the elephant in the room. Outside of excellent changeups, the other thing all three of these pitchers have in common is a mediocre-to-bad fastball.

| Player | Velo | Horizontal movement | Vertical Movement | Spin Rate | Active Spin % | Usage% | pVAL | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 91.7 | 13.3 | 5.9 | 2376 | 91.10% | 50.70% | 2.9 | 0.328 |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 87.2 | 21.7 | 6.7 | 2044 | 75.80% | 62.20% | 10.3 | 0.248 |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 89.9 | 17.8 | 2 | 2326 | 74.50% | 46.50% | 16.9 | 0.294 |

Now there are a few things to unwrap here before we get into location. I want you to pay special attention to Means’ spin rate for his fastball. Let’s take that info and combine it with some additional stats.

| Player | SwStr% | LA | K% | O-Swing% | O-Contact% | Zone% | GB% | xBA on FB + PU | BA on FB + PU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 7.00% | 22.4 | 19.90% | 21.10% | 77.50% | 50.50% | 26.40% | .179 | .138 |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 12.30% | 26.3 | 26.20% | 24.70% | 61.20% | 53.70% | 23.50% | .165 | .172 |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 6.40% | 20.4 | 22.30% | 20.00% | 81.60% | 59.80% | 31.60% | .190 | .158 |

If you take a look at a study done by the folks over at Driveline, there is a connection between spin rate/velocity and how a pitch should perform in terms of SwStr% and launch angle. According to the article, given Means’ spin rate and velocity, his SwStr% should be closer to 9% and his average launch angle should be closer to Hendricks’ 26 degrees. This would help by hopefully generating more popups and poorly hit fly balls, something Means already excels at with his other pitches. A 2% bump in his SwStr% could mean a lot in terms of his success with the pitch. So why did it underperform in these areas? Let’s head back to the zone charts.

So we want fastballs up in the zone, right? 37.3% of his four-seamers were up and out of the zone. 16.5% of them were up and in the zone. 11.7% were down and in the zone (not ideal), and 15.8% were down and out of the zone. In the long run, 53.8% of his fastballs were where we want them. He had an xBA of .181 with an 8.5 SwStr% on those four-seamers up.

Hendricks, on the other hand, threw 39.3% of his fastballs up and out of the zone and 22.1% up and in the zone. A scant 7.0% were down and in the zone, with 8.9% being down and out of the zone. On the 61.5% of fastballs he threw up in the zone and out of it, hitters managed a .166 xBA with a 10.2 SwStr%.

Finally, Greinke had a different approach. Greinke threw his fastball down in the lower part of, and out of, the zone 47.4% of the time. I suspect that since the speeds of his changeup and four-seamer so closely resemble each other, it was in his best interest to throw them in similar spots to help disguise which pitch was coming until it was too late. Most likely, we would want Means to follow Hendricks’ fastball blueprint in 2020 in this case.

Slider

This will simply be a comparison between Greinke and Means, since Hendricks doesn’t throw a slider. Means’ slider has near league-average movement with decent velocity. It has some promise in terms of its strikeout potential, given the 31.6% O-Swing and 13.0% swinging-strike rate. Both of these numbers will have to improve if the pitch is to realize its true potential, but there are at least some signs that few tweaks could make this pitch into the perfect wipe-out pitch that he needs. About 49% of the sliders he threw came with two strikes. In fact, in many ways, Means’ slider outshines Greinke’s, and arguably he should throw it way more often than he does.

| Player | Velo | Horizontal movement | Vertical Movement | Active Spin % | Usage% | pVAL | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 83.9 MPH | 33.4 | 4.6 | 31.90% | 14.90% | 3.2 | 0.233 |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 83.7 MPH | 39.7 | 7.1 | 35.00% | 15.90% | -2.2 | 0.307 |

Despite a difference in their movement profiles, you can see they’re pretty similar sliders that got very different results. Why?

| Player | K% | O-Swing% | O-Contact% | Zone% | SwStr% | GB% | EV | LA | BBL% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 22.10% | 31.60% | 54.10% | 39.40% | 13.00% | 33.30% | 85.1 | 16.4 | 3.30% |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 20.10% | 37.90% | 60.70% | 32.40% | 12.00% | 50.00% | 85.7 | 7.8 | 4.70% |

The first thing that jumps out at me is the difference in launch angle and BBL%. While Greinke uses his slider to induce weak ground balls, Means does the opposite. He gets a ton of weak fly ball outs through his slider.

| Player | BIP Below 89 MPH | Fly Balls below 89 MPH | %BIP = FB under 89 MPH | FB Distance under 89 MPH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 39 | 10 | 16.70% | 271 ft. |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 60 | 8 | 7.50% | 271 ft. |

This is fascinating. We tend to focus on staying away from pitches that draw fly ball contact, but in reality, there’s nothing safer for a pitcher than a weak fly ball. It’s also worth noting that Means had a 27.3% IFFB rate with his slider. This could be evidence that Means’ slider can continue to be an effective weapon even if it doesn’t get more strikeouts. If there’s one common thread to Greinke and Hendricks, it’s that they tend to be overlooked because they have a knack for drawing weak contact as opposed to striking folks out. It’s a repeatable skill and many of the signs seem to indicate that Means could potentially have the same ability. It’s not sexy, but it’s effective, and it gives me confidence to see him drawing the same kind of contact, even if he isn’t doing so on the ground.

Movement and contact profiles are only half the battle, though. Hopefully, if I’ve driven anything home in this article, it’s that where you throw a pitch matters as much as how you throw it, and the slider is no different. We want sliders down in the zone, and when Means throws his slider at the bottom of the strike zone, it gets killer results.

| Player | Sliders Thrown | % Thrown at Bottom of Zone | SwStr% at Bottom of the Zone | CSW% at Bottom of the Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 386 | 10.4% | 17.5% | 35.0% |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 457 | 22.1% | 12.9% | 32.7% |

A 35.0% CSW is fantastic, and as you can see, he gets a ton of swings and misses in that bottom portion of the zone. Means just needs to throw it there more often and it could take off. The weird thing is, despite its fantastic SwStr% and CSW%, Means rarely threw it with two strikes, which is why he struck out only one batter with his slider down and in the zone. Based on his CSW%, that number should be closer to six or seven if he threw it more often as a strikeout pitch. That alone would have bumped his K% above 20%.

This pitch has all the making of that third pitch Means will need to fully hit his ceiling. He currently throws it just 14.4% of the time. I would love to see him get that number up to 20% or more, either by cutting back on his fastball usage or by eliminating his curveball (which he threw 5.9% of the time) and focusing on the slider. If you add in throwing it down in the zone more often with two strikes, we’re talking right around a 21% K rate. That doesn’t seem like much, but that’s just from improvement in one pitch in one location! Suddenly, he’s just a few percentage points away (essentially 14 strikeouts) away from a strikeout per inning, which could greatly increase his chances of success in the majors.

Curveball

Speaking of his curveball, let’s wrap up the pitch comparison with Means’ curve. All three of these hurlers throw a curveball, but while Greinke and Hendricks have found a lot of success with their curveballs, Means has not. Let’s line them up against each other.

| Player | Velo | Horizontal movement | Vertical Movement | Active Spin % | Usage% | pVAL | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 77 | 51.9 | 3.8 | 50.60% | 5.90% | -4.7 | 0.517 |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 71.4 | 68 | 15.7 | 84.80% | 9.80% | 2.4 | 0.218 |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 70.7 | 68.9 | 12.4 | 78.70% | 15.40% | 13.2 | 0.203 |

Some of the issues crop up right away. Means’ curveball doesn’t have nearly the vertical drop of Hendricks’ or Greinke’s, and much of that seems rooted in the lack of spin-related movement. This causes his curveball to lack much of the deception that a successful curveball might have.

| Player | K% | O-Swing% | O-Contact% | Zone% | SwStr% | GB% | EV | LA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 22.70% | 19.40% | 47.40% | 38.80% | 7.00% | 35.30% | 87.3 MPH | 15.2 |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 31.30% | 28.60% | 60.50% | 49.40% | 8.00% | 44.80% | 84.7 MPH | 14.7 |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 25.00% | 43.50% | 57.70% | 47.40% | 17.00% | 46.70% | 83.4 MPH | 11.1 |

This is the other major issue Means runs into with his curveball. While he throws it in the zone the least, he doesn’t get anyone to chase outside the zone, and those two things are absolutely linked.

| Player | Total Curveballs | % in Bottom of Zone | Swing% in Bottom of Zone | SwStr% in Bottom of Zone | CSW in Bottom of Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 165 | 16.30% | 37.0% | 7.40% | 55.60% |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 265 | 25.70% | 44.1% | 10.30% | 54.40% |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 455 | 20.40% | 77.4% | 26.90% | 46.20% |

Means had the best CSW% of all three pitchers when they threw their curveball in the bottom of the zone. Unfortunately, he threw it there the least. Also, when hitters made contact, they crushed it, hitting .667 with a 1.500 SLG. It’s worth noting, though, that it was only put in play six times when he threw it down there, and based off a .600 BABIP, there might have been some positive regression in a greater sample.

The numbers for when Means throws the curveball down and out of the zone is a whole different story, though.

| Player | Total Curveballs | % Down and Out of Zone | Swing% Down and Out of Zone | SwStr% Down and Out of Zone | CSW Down and Out of Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 John Means | 165 | 47.30% | 19.2% | 11.50% | 14.10% |

| 2019 Kyle Hendricks | 265 | 34.30% | 28.6% | 13.20% | 14.20% |

| 2019 Zack Greinke | 455 | 44.20% | 47.2% | 19.50% | 23.40% |

It’s important to recognize that when discussing called strikes out of the zone, that is a combination of the pitcher’s ability to throw just outside the zone and the catcher’s ability to frame the pitch (and perhaps umpire blindness), so there is some variance there. Nevertheless, Means threw his curveball out the zone the most of the trio, yet the pitch had the lowest Swing% of all three. Why is that?

This is where Greinke’s curveball shines. It has the second-highest percentage in the bottom of the zone, with far-and-away the highest Swing% for that location. His curveball also has the second-highest percentage down and out of the zone, with the highest CSW% and once again easily the highest Swing%. This is because Greinke so effectively mixes throwing his pitches to these two spots. Since he establishes that he can throw the curveball for strikes at the bottom of the zone, the hitter can afford to lay off the pitch just because he sees a curveball, since it might still drop down into that lower region of the zone for a strike. Hendricks does this pretty well too, even if he doesn’t throw down and out of the zone as much with his curveball. Means, on the other hand, throws his curveball out of the zone more than either pitcher, but gets fewer swings because the hitter knows he doesn’t throw it for strikes. They see a curveball and know to lay off. Changing this will be the key to this pitch becoming more effective, especially when you consider its great CSW% when thrown in the bottom of the zone.

Conclusion

What does this all mean for John Means? (See what I did there? Not even a courtesy chuckle? Fine.) Right now, Means is a thrower who has one elite pitch, two pitches that, with better command, have all the makings of being good-to-great offerings, and a fourth pitch that needs a lot of work to be usable. He’s likely never going to be an elite strikeout pitcher who will be reliant on ball placement and generating weak contact if he wants to continue to make the leap from promising young pitcher to a core rotation piece for the Orioles. Since he doesn’t strike a ton of folks out and sports a low-velocity fastball, most have been pretty dismissive of his chances of making that leap in today’s MLB environment. What I hope we’ve accomplished by comparing Means to two elite pitchers who fit the same profile is to demonstrate that, with a few tweaks to where throws his pitches and how he utilizes them, he could become a really solid big league pitcher for quite some time. I know that I will be watching as many of Means’ spring training and early-season innings to see if he shows signs of commanding those pitches better and using his slider more. If he does, he could be a steal in most drafts.

To put this all back into a fantasy baseball perspective, Means is currently going around pick 374 (the 132nd pitcher) on average in NFBC drafts which means (ha!) he’s a last-round pick right now. That’s basically free. Based on his 2019 success, that’s pretty much the perfect last-round flyer to round out a staff. If he has a repeat of his 2019 season, that’s a tremendous value. What feels like a realistic expectation for his season? I think it’s reasonable to expect something between a 3.75-4.00 ERA with around 180 IP and between 160 and 180 Ks. In terms of his ceiling, I think Kyle Hendricks (3.50 to 3.60 ERA with 160 to 180 IP and a strikeout an inning) represents the logical max ceiling this season for Means if he continues to grow in his second year, with current Greinke representing the ultimate, everything-goes-right-in-his-career sorta ceiling. The important thing to take away from this article is that, with a few tweaks to his pitch mix and how he uses them, there is a path to him becoming a valuable pitcher both in real life and fantasy. Perhaps even more importantly, we as fantasy owners and fans now know what we need to look out for so we can tell if Means is indeed on his way to a breakout sophomore season.

Photo by Keith Allison/KA Sports Photos | Adapted by Rick Orengo (@OneFiddyOne on Twitter)