From 2018-20, 75 pitchers threw 300+ innings. Over that stretch, Aaron Nola was 2nd in IP, 10th in ERA, 6th in strikeouts, 6th in wins, 15th in WHIP, and 8th in fWAR. No matter how you look at it, he was one of the very best pitchers in baseball during that three-year run, and there was no reason to think he would be any less than that in 2021.

And then he was less than that. He threw his fewest innings since 2017 (assuming pro-rated 2020 innings) and posted his worst ERA since 2016. He struggled in 2021 and it’s worth asking why.

Maybe He Didn’t Struggle

I just said he struggled, and now I am saying maybe he didn’t? That doesn’t make sense!

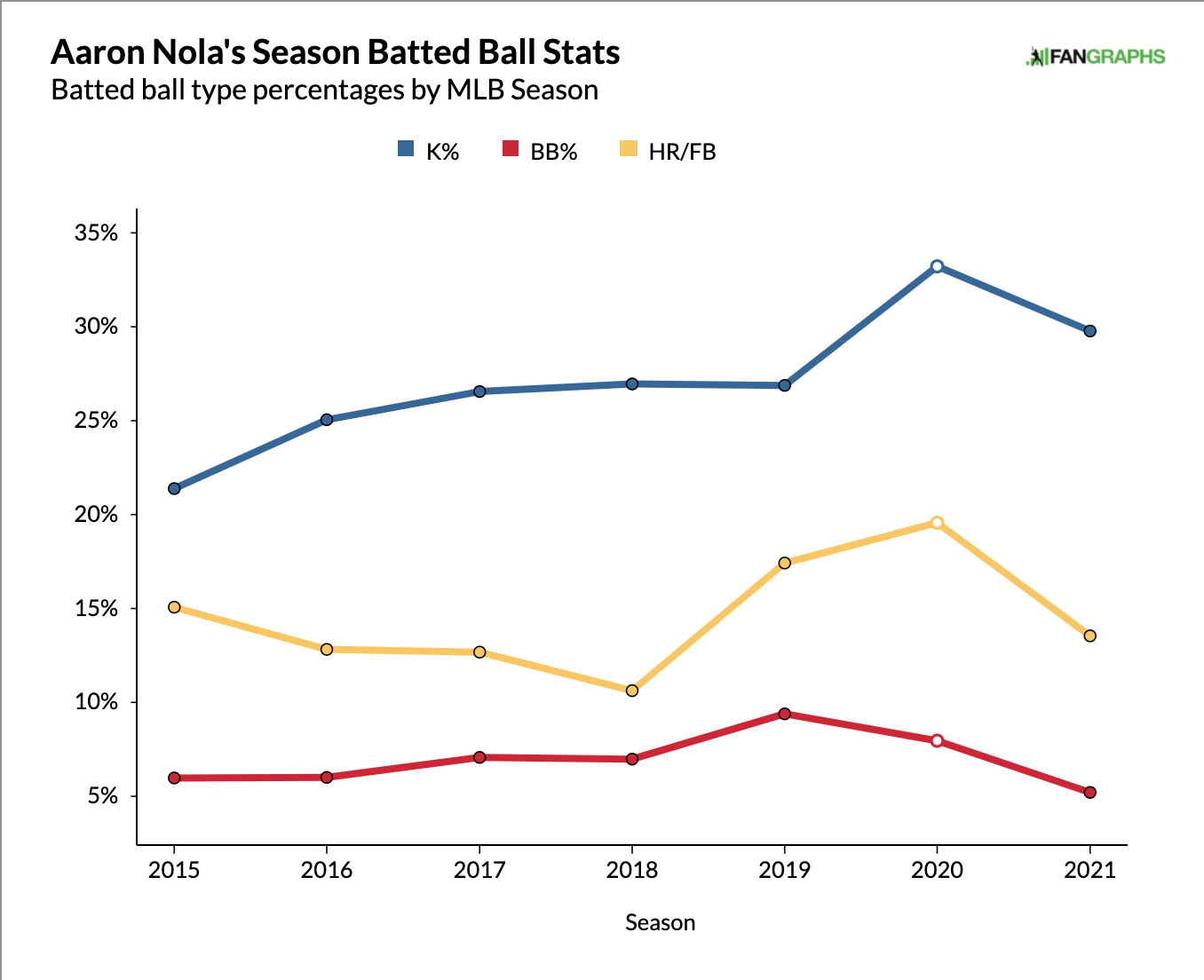

Except we all know that ERA isn’t the entire story and by some very important measures, Nola looked… well, he looked like Aaron Nola. There are three outcomes a pitcher cares most about — strikeouts, walks, and home runs. Nola was good on all three.

No matter what ERA tells me, that looks like a good season: HR/FB rate is down vs. 2020 and in-line with much of his career; that strikeout rate is the second-highest of his career, and his walk rate is the best of his career. That’s pretty good.

Of course, that isn’t the whole story — it can’t be the whole story, because if it were we wouldn’t be here sweating over his rough season.

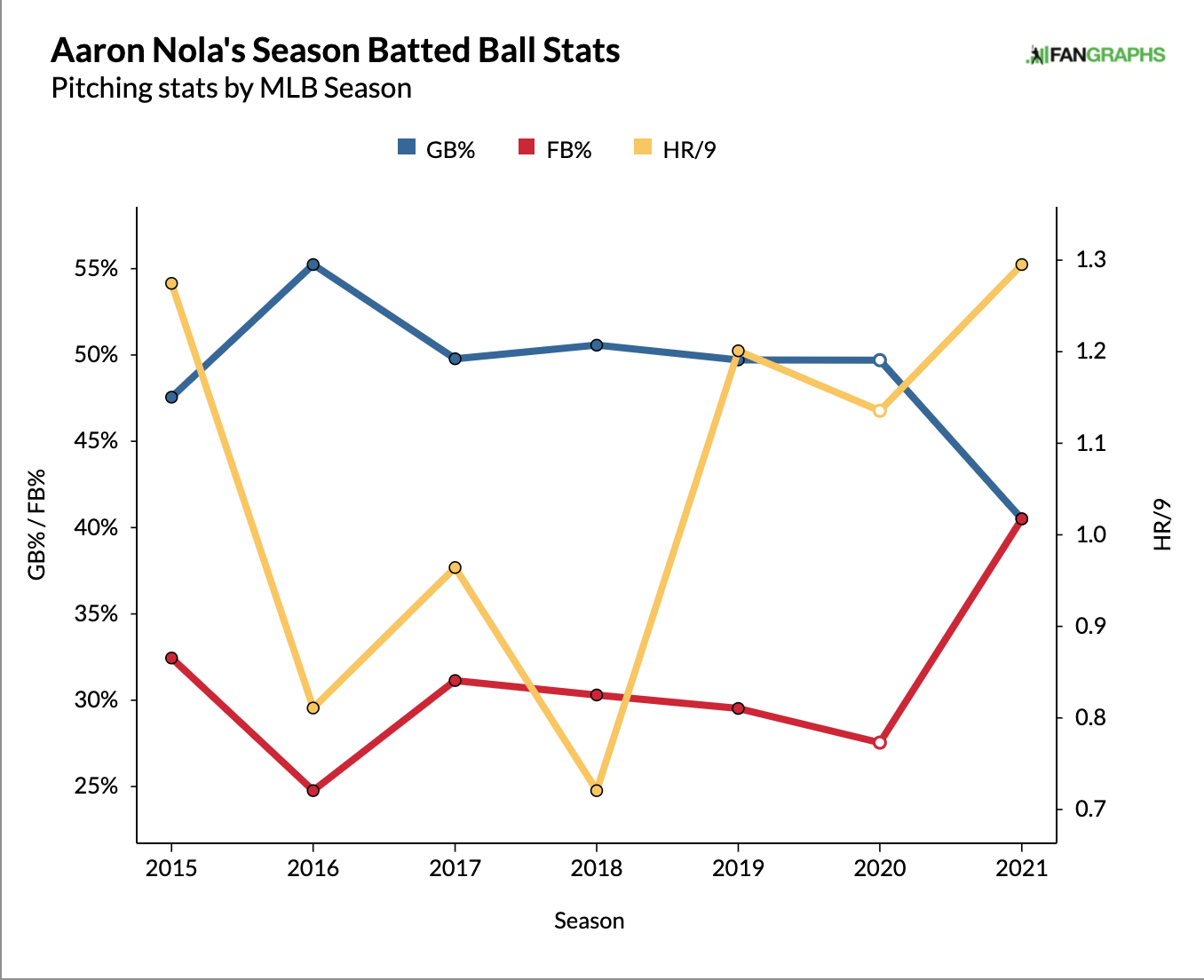

For one thing, just because Nola didn’t give up more HR/FB doesn’t mean he didn’t give up more HR. In fact, he did give up more HR.

Ok, that is interesting. His ground-ball rate dropped while his fly-ball rate jumped, so while his HR/FB rate was down, his HR/9 was up. More fly balls, even if fewer of them fly out of the park, can lead to more total home runs allowed.

So that is also part of the story, but it still isn’t the whole story. His FIP (3.37) was in-line with his career norms, and it was much better than his ERA. Homers are part of the equation for FIP, so if the issue were primarily around home runs allowed, his FIP would have jumped. It didn’t, so there has to be something else at work here.

What else can cause a gap between FIP and ERA? Well, the equation for FIP includes HR, BB, HBP, and K, so we have to look at things that fall outside of that.

Where’s the Red Flag?

The two primary culprits for ERA ballooning up away from FIP are BABIP and Left-On-Base rate. In general, we expect pitchers to land close to league average on both of those measures (though we know that is not always the case), and so a lot of key measures of pitcher success (FIP, xFIP, SIERA, K%-BB%, CSW) leave those out of the equation.

High BABIPs can be a result of bad luck or bad defense and the Phillies defense was either middle of the pack or pretty bad depending on whether you prefer UZR (-0.2 UZR/150, 14th in MLB) or DRS (-54, dead last in baseball). Nola did, in fact, have an inflated BABIP. Nola has a career .293 BABIP and during that run from 2018-20 it was .274. In 2021 it was .308.

That’s not good but that is not “explain a 1.26 gap between ERA and FIP” bad. Nola faced 749 hitters in 2021. After taking out 223 strikeouts, 39 walks, 9 HBP, and 26 home runs, that leaves 452 balls in play. The .015 increase in his BABIP vs. his career number, across 452 balls in play, means about seven additional hits. If you prefer to compare to his 2018-20 .274 number, that is an extra 15 hits. That doesn’t come close to explaining the roughly 25 runs difference between his ERA and his FIP.

Left-On-Base percentage is effectively a measure of sequencing of results. If two pitchers face ten hitters with three strikeouts, one walk, two hits, once could give up 0 runs while the other gives up three, just based on the order of the events.

And this starts to explain the gap for Nola. For his career, Nola has a 74% LOB%. For 2021, it was 66.8%. That is an additional 7.2% of all baserunners he allowed coming around to score. The difference between those two numbers is about 11 runs scored. That isn’t a full explanation of how Nola ended up with an ERA so much higher than his FIP, but it goes a long way.

So some rough defense and poor batted-ball luck hurt Nola. And an increase in fly balls hurt Nola. But the bigger impact was the number of runners he failed to strand.

While it would be tempting to say that Nola just suffered bad luck in the sequencing his batters faced, there is more to it than that. Aaron Nola was really bad with runners on.

Struggles from the Stretch

He struck fewer batters out, walked more guys, gave up more HR, and generally performed worse. This wasn’t just bad sequencing, it was bad performance.

Looking back at Nola’s career, this appears to be a new issue for him. The table below shows his career numbers coming into 2021.

Depending on what numbers you prefer, he was arguably better with runners on in his career than with the bases empty. It’s probably more accurate to say he’s been no better or worse — fewer K, similar walks, better HR/FB numbers; a nice improvement in FIP with men on, but a jump in xFIP. There just isn’t much daylight between those two rows. Pitchers in general perform better with the bases empty (league-wide FIP with the bases empty was 4.18 vs. 4.37 with men on in 2021, though there is some selection bias skewing that). But Nola hasn’t performed worse with men on over his career, and that makes his 2021 is a major outlier.

So this is getting interesting! Nola didn’t just have a rough season where his BABIP was a bit high and he had bad luck stranding runners — he seems to have had a real issue with his performance once men got on base.

Going a level deeper, it appears he might be having an issue with certain pitches with guys on base.

Let’s ignore the cutter, given limited usage. The four-seamer and curve are used a bit less with men on base, but the performance isn’t hugely different. Yes, the four-seamer is a touch better, and the cure is a bit worse, but they are pretty small differences. By xwOBA, the four-seamer gets even better with men on and the gap for the curve gets smaller. Not a lot to see there.

But the change and sinker performed a lot worse (and you see the same pattern if you look at xwOBA). So what we have is Nola doing something that seems logical, but it isn’t working out. His change and his sinker, used about 1/3rd of the time with the bases empty, are his two best performing pitches, at least measured by wOBA allowed. So, naturally, when he gets into trouble, he goes to those pitches a bit more often (an extra ~4% of the time). But they perform a lot worse.

Given how small the change in pitch mix is, I doubt this comes from hitters expecting and therefore sitting on the change or sinker. Sitting sinker because you might see 1 or 2 more of them out of the next 100 pitches is unlikely to be a successful strategy.

Maybe those pitches look different?

Nothing looks drastically different, though there are some concerns — the increased spin on the change seems less than ideal, as does the decreasing gap between his fastball velocity and his changeup velocity. The other changes all seem relatively small and unlikely to hurt.

I looked at break on the pitches and found some similarly small and generally unnotable differences. Nothing to write home about.

But there are a couple of things that might point at an issue.

Location, Location, Location

Nola’s release point when he is from the stretch is not the same as from the windup. The difference isn’t huge, but it’s something. And the difference is much larger than for other top pitchers.

To look at this, I took the X and Z coordinates for release point from Baseball Savant and calculated a distance in inches between release points for a pitch with the bases empty vs. men on base. I did this for Nola, Gerrit Cole, and Brandon Woodruff, as well as the league as a whole:

A lot to parse there, but there are two things that stand out:

- Release points are not the same coming out of the stretch vs. the wind-up. That isn’t a huge surprise, given the different mechanics, but it’s still worth noting.

- Nola’s release points moves a lot, relative to the league and relative peers.

Looking back at 2019-20, Nola was much tighter on his release points with men on vs. the bases empty. For example, instead of a 1.08 inch difference on his changeup, he had a .73 inch difference.

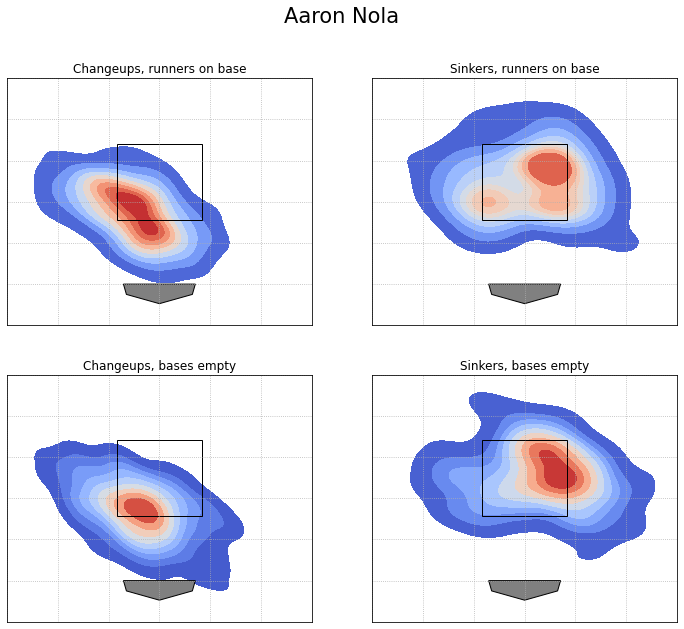

Second, below are four heat maps, comparing the location on the sinker and the change — the two problematic pitches — with men on vs. with bases empty.

The changeup is more glaring. With bases empty, Nola is burying the change down and in the corner. With men on, his location is far less consistent and there are a lot more changeups left out over the plate, where they can get crushed.

The sinker, meanwhile, is staying up a little higher and staying out over the plate, where — like the changeup — they are more likely to get crushed.

A Disclaimer

Before we go any further, let me say I am not a pitching coach. Which cause two issues with this analysis. First, I am not actually sure if we should be concerned about this release point difference or this location difference. Is the extra half-inch vs. Cole or Woodruff really that scary? Is the location different for good reason (i.e., avoiding walks or trying to induce more double plays)? Is any of this actually driving his struggles with guys on base? I am not sure. What I can say is the following:

- Nola struggled in 2021

- Those struggles came despite solid strikeout and walk numbers, and were driven heavily by an inability to strand runners

- Those runners coming around to score was not just bad luck or sequencing, but a result of decidedly less effective pitching with men on base

- His release point with men on base is, in relation to his release point with bases empty, an outlier

- His location with men on base is, in relation to his location with the bases empty, less precise and possibly less ideal.

Beyond that, I am getting into speculation, and there are probably lots of answers/ideas that I have not thought of. That said, I wanted to take a look at him throwing from the stretch and from the windup to see if we could see an obvious difference.

Do We See a Mechanical Issue?

The following GIFs are taken from two plate appearances on the same day (September 29) against the same hitter (Ozzie Albies) and feature the same pitch (four-seam fastball). The first is with the bases empty, the second with men on. I wanted to look at three points in time — the high point of his leg kick, the moment he is planting his left foot, and the release point.

First, note that the camera angle, while from the same park and the same game, is not exactly the same, so there will be some small differences caused by that. But, to start, it does not look like Nola has changed where on the mound he sets up. In both cases, his back foot is right at the first base end of the rubber. However, it does appear that from the wind-up he is at a slightly higher point at his peak than from the stretch. Maybe that is an artifact of my editing, so take it with a grain of salt, but it looks to me like he isn’t getting quite as high up, at least in this case. Is that a major difference? Probably not (especially after accounting for my influence), but it is something.

This time, I think my editing is a bit off, but part of the challenge here is that with no one on, it is harder to see Nola’s front foot. With men on, his stride is slightly more towards third base which leaves his front foot more visible from this angle. No matter how many times I cut this, that was the same.

At release, you can see the same thing — his front foot is a bit further towards 3B with men on base and is more visible in front of his back leg.

Again, I am no pitching coach, but there look like there may be some slight differences in the mechanics, which may tie to the different release points, which might tie to the different results.

What to Make of All This

For me, the big takeaway is there is an explanation for why Nola had such poor results compared to his strikeout and walk numbers. He struggled with men on, leading to a decrease in LOB% and the blown-up ERA. There is also good evidence that his HR issues were tied to his LOB issues. Yes, he had a career-high HR/9, but his HR/9 with the bases empty was much better and much closer to his career numbers (1.13 career HR/9 with the bases empty; 1.19 this year).

Next, there may be a mechanical issue behind those struggles. It’s possible that what I am interpreting as a possible mechanical issue is just noise, but either way, this gives me a lot more confidence drafting Nola in my fantasy leagues. If there is a mechanical issue, he has the offseason to look at what went wrong with men on base (ideally with people smarter than me), figure out the issue, and correct it. If what I think is a mechanical issue is just noise, then his performance with men-on-base should normalize towards his overall numbers next year. Both are good results.

On top of that, by strikeouts and walks, Nola is coming off the two best seasons of his career. He looks like a guy trending down on the surface, but beneath that, you have a guy who might be at his absolute best. The decrease in ground-ball rate is the biggest red flag for me. However, he performed just fine despite that, and we can’t ignore the possibility his GB% rebounds.

Before the 2021 season, Aaron Nola had an ADP at NFBC of 22.9. In early 2022 drats, he is going at 41.2. He is not, in my opinion, nearly 2o picks worse today than he was before the season. I would gladly take him at the new lower price, and benefit from what I suspect will be a pretty spectacular rebound.

Photo by Kyle Ross/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)

Chad, great read! Thanks